Ugly Democracy: Towards Epistemic Disobedience in Development Education

Development Education and Democracy

Abstract: In the current context of global threats to democratic life, through a rise in fascism, populism and right-wing governments, the thirty-sixth issue of Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review calls and opens a space for reflecting on ‘development education’s distinctive and rounded view of democracy’. This article answers the call by engaging with this current problem-space and the answers development education in Europe have historically mobilised in response to it (Scott, 2004). Rather than starting from the position that the current forms of violence we are witnessing are not democratic or ‘real’ representations of freedom, the article addresses democracy – a modern construct – in its entirety, examining the entanglements between democracy, development education, and modern/colonial systems of oppression. Drawing on political perspectives from contexts where democracy is assumed and contexts where it was imposed, the article aims to dislodge the self-evident position of democracy as the universally desirable answer for development education, and consider the possibilities opened by starting from a position where democracy is part of the problem as well.

Building on, and contributing to, decolonial scholarship in the field, the article draws on Elizabeth R. Anker’s (2022) study of ugly freedoms as a framework from which to complexify discussions about democracy and consider possibilities for thinking about development education differently – through more compromised, understated engagements with global issues that resist investments in purity, ‘doing’ and certainties, opening different possibilities for thinking and experiencing freedom. The article ends by suggesting a set of reflexive questions that might support interrogations of democracy in development education practice.

Key words: Development Education; Decolonial Critique; Critical Global Citizenship Education; Epistemic disobedience; Democratic Education.

Introduction

In the context of recent attacks on democracy by a rise in fascism, authoritative governments (Giroux, 2022b) and necropolitics (Mbembe, 2019), this issue of Policy and Practice calls on scholarship to consider the role of democracy in helping to (re)politicise development education and promoting critical consciousness and freedom from domination. By focusing on developing a ‘distinctive and rounded view of democracy’ in the field, Issue 36 offers a space where we can bring to the fore a concept that is perhaps referred to a lot in development education but sits mostly in the background. Democracy is a notoriously contested concept (e.g., Sant, 2021), but we can broadly take its meaning from the call for contributors, and elsewhere in the journal (e.g. Giroux, 2022a), as bottom-up collective action rooted in dialogue and participation, leading to liberation. Despite the controversy around its meaning, democracy tends to assume a universal desirability and be presented as the antidote to its own, and other, global crises (Zembylas, 2022). Because of this self-evidence, democracy is easily positioned as the answer to our questions.

This article raises the question of what other answers might become available when democracy is positioned as also part of the problem and considers how centering democracy in development education might open/foreclose possibilities for thinking about practice otherwise. It responds to the call for contributors by critically engaging with the problem-space (Scott, 2004) informing it, particularly focusing on interrogating and historicising the concept of democracy and positioning it as part of/enabling the problems we are currently facing. In its critical reflection, the article finds parallels between democracy and development as two North Atlantic Universals (Trouillot, 2009), and raises implications for thinking about these concepts differently in development education in European contexts.

The problem of democracy for development education

Development education is strongly influenced by a critical pedagogy tradition (Stein, 2018), and the call for contributors for this issue is largely set up as a response to Henry Giroux’s construction of our current democratic crisis as partly enabled by education. In a couple of recent articles, Giroux (2022a; 2022b) provides a prolific overview of the consequences of right-wing politics and neoliberalism for democracy and education, and outlines how education is to respond to it. Giroux (2022a) explains how right-wing governments’ return to fascism has made visible and legitimised the mechanisms of white supremacy (i.e. racism, violence, systemic inequality, environmental destruction), ethicide (the erasure of ethical questions and referents from politics), and necropolitics (the power to decide who gets to live and who can die) (drawing on Mbembe, 2019). Moreover, in the era of ‘fake news’, governments and social media have waged an attack on the truth, critical thinking and questioning, which Giroux argues are key for an informed citizenship. Coupled with right-wing politics, neoliberalism has carried the logic of the market into all spheres of public life, disavowing basic human rights, and corrupting collective democratic spaces. Although Giroux is speaking from a United States (US) context, we can see similar developments in the United Kingdom (UK). The cost-of-living crisis, the dehumanising treatment of refugees and asylum seekers as well as the promised ‘tougher’ rules on collective union action are just some examples.

In Giroux’s framing of our democratic crises, we can identify a clear distinction between democracy and the violence, oppression, and marginalisation enacted by governments and other global institutions. In this context, Giroux argues that education has become a tool for authoritarian control and reclaims education’s obligations to democracy, social justice and freedom. His response is abundant with principles that can help education address the siege on democracy. We might summarise these as largely based on targeting knowledge production in the classroom, since Giroux maintains the continuous moves toward authoritarianism are a consequence of ignorance, misinformation and historical amnesia (Giroux, 2022a; 2022b). Consequently, he argues the development of critical literacy is key to uncover the truth and save democracy, since ‘democracy cannot exist or be defended without critically literate and engaged individuals’ (Giroux, 2022b: 115). Teachers’ responsibility is to assume the role of citizen-educators, and support students’ critical reading of the world, in ways that promote an educated hope, so that they feel empowered to act. In Giroux’s response to his framing of our current problem-space, there is a clear journey through a critical pedagogy education that leads to the acquisition of the knowledge needed to develop a sense of agency and empowerment, which will then lead to freedom. Through critical pedagogy, education can ‘win the war’ with fascism (Giroux, 2022b).

Stein (2018) has recently made a case for the need to engage from a range of critical perspectives with the concepts we have inherited from modernity and consider the ways in which they constrain/enable our thinking about, and responding to, our present problems in development education. Hence, this article engages with the concept at the centre of this issue on democracy and considers the answers we might mobilise/assume from within a Eurocentric imaginary. The next section engages with decolonial scholarship in international development and education to discuss democracy as a constitutive concept of Eurocentric epistemology and, as such, delimiting possibilities for thinking and making sense of our global problems. Next, the article makes a case for re-framing our problem-space, by arguing that the current violence and oppression we are witnessing globally are not only an attack on democracy but have also been enabled by it. The aim is to target the Eurocentric imaginary, via one of its constitutive concepts (democracy) (Mignolo, 2018) and to make visible other ways for thinking about our current problem (democratic crisis), via other points of entry to the conversation. Through this exercise, we might be able to re-frame the problem of democracy and also think differently about freedom in development education. These two steps are important, because as Stein (2018: 3), drawing on Scott (2004), argues ‘it is not only concepts that might need to be rethought, but also our modes of critical engagement, knowledge production, and theories of change’. In line with Stein, this article does not aim to offer a final perspective on the problem of democracy but to contribute to our current thinking about approaches to development education, by interrogating our assumptions and bringing into conversation different critical perspectives.

Dislodging democracy as self-evident in development education: key contributions from decolonial engagements

Decolonial scholars in the field of international development (e.g. Santos, 2016; Mignolo, 2018) argue that we cannot continue to look for modern answers to the problems caused by modernity. Yet, research and practice in development education in Europe suggest we continue to struggle to question/move beyond modernity’s concepts in our attempts to address global issues (Pashby and Sund, 2020). This investment in modernity and its promises maintains a circularity within conversations in development education (see Pashby et al., 2020) and limits possibilities for thinking about alternatives. So, how can democracy offer a conceptual tool to develop, as Santos (2016: 133) suggests, ‘alternative thinking of alternatives’ in development education? Addressing this question requires perhaps what Mignolo (2018) has called epistemic disobedience, by which he means recognising and denaturalising modernity’s concepts. Hence, a starting point might be to dislodge the place democracy holds in our modern imaginary, as inherently good and the only solution to our current problems (e.g. Rockhill, 2017; Zembylas, 2022). We can build off a long history of questioning, contesting and reframing, democracy that reaches back to its emergence in Greek philosophy and has led to a plurality of critical engagements with the concept (see e.g. Held, 2006), which have been translated into a wide range of approaches to democratic education (see e.g. Sant, 2021). Among these critical engagements, some scholars have, in line with decolonial critiques, pointed to the constraints imposed by the modern principles on which the idea of democracy is built, i.e. individualism, logical reasoning and linear thinking (Sant, 2021). Nevertheless, although this scholarship interrogates democracy, it tends to remain framed by it, albeit through more sophisticated/ radical definitions (Rockhill, 2017).

With democracy positioned as the reference for thinking about political engagement (Rockhill, 2017), we might think of it as a constitutive concept of modern epistemology, and as functioning as a final boundary for critical thought. In this way, critical theory might problematise democracy, but not delink from it (Mignolo, 2018). This is arguably a challenge that comes with thinking about alternatives from within Eurocentrism – the regionally located, but universally imposed imaginary that marginalised other ways of knowing and making sense of the world (Santos, 2016 Mignolo, 2018). ‘Eurocentric critiques of Eurocentrism’ (Walsh and Mignolo, 2018: 3) mostly readjust the content, but do not ‘change the terms of the conversation’ (Mignolo, 2018: 149). This limitation is felt markedly in the context of international development and the complex global crises we are facing, because it vastly restricts the perspectives available to think with (Santos, 2016).

Recently in education, Zembylas (2022) has targeted the self-evidence of democracy, by drawing on decolonial scholarship. He argues that democracy has been taken for granted as the ‘only possible cure for racism, sexism, economic injustice (…) and all other ills in societies’ (Zembylas, 2022: 160), without an understanding that these issues have also been enabled by, or are a consequence of, democracy. Consequently, he calls on democratic education scholars to take up the relations between democracy, modernity, capitalism and colonialism. Zembylas argues that, without this examination, democratic education will remain limited in its ability to provide alternative responses to our present social issues. He concludes by calling for a decolonial ethics in radical democratic education, based on a politics of ‘refusal’ of liberal democratic norms and values, and the inclusion of Indigenous knowledges, traditions, and practices in education. According to Zembylas (2022: 161), drawing on Brooks et al. (2020), this approach supports a disinvestment from Eurocentrism through ‘the production of Indigenous knowledge systems that are distinct from the coloniser’s influence’.

Despite the decolonising approach of Zembylas’s (2022) critique of democracy, the response seems largely based on another effort to pluralise knowledges in education, so as to reach a more (radically) democratic approach. In this way, although democracy is positioned as part of the problem, it remains largely the solution. As such, Zembylas’s critique retains a teleological commitment to democracy as something we arrive at (if we play our cards right), and raises questions for thinking about democracy in development education: is there a possibility for a different kind of critique? And what theoretical tools can help target and challenge modern epistemological dominance in conceptualisations of democracy and freedom? Is it possible to start with, but not end in, a new (decolonial) approach to democracy? Understanding democracy as an inheritance from a Eurocentric imaginary makes it an important starting point for conversations; as a concept we can (un)learn from, so that we might think about development education differently. However, it is important this starting point remains opened, and does not fall back on the normative frame we are imposed when democracy is put into question (Zembylas, 2022), so that we might draw on democracy when its useful, but not have it be the only possibility available (Mignolo, 2021). The following section starts by answering Zembylas’s (2022) call to address the entanglements between democracy, violence and freedom. In this effort, the article arrives at a more complex (and compromised) starting point for democracy, which is enabled by an engagement with counter-histories (Rockhill, 2017) and Anker’s (2022) conception of ugly freedoms.

Democracy, development and ugly freedoms

Democracy and development are both modern concepts that have long informed and framed discussions about global issues. Democracy is inscribed in our Eurocentric imaginary in such a way that it is ‘extremely difficult to speak of democracy without presupposing its intrinsic value’ (Rockhill, 2017: 52). Similarly, development has long been taken for granted as not only desirable, but essential, and as the only frame for thinking about, and addressing, global inequalities (e.g. Escobar, 1999). Both democracy and development are what Trouillot (2009) called North Atlantic Universals – words specific to a local region that have been projected universally, both describing and prescribing the global standard. This projection was enabled through the systems of oppression ignited with colonialism (Trouillot, 2009; Mignolo, 2021), placing democracy, development and coloniality in an intimate relation that requires that their history is told in conjunction (Zembylas, 2022). Through this process, we are more likely to shed light on the double violence played by European democracy: first, as the enabler of colonialism, and then as the promoter of ‘freedom’.

European political thought, placing its origins in Greek philosophy (Rockhill, 2017; Mignolo, 2021), often fails to recognise that from its very beginning, democracy was thought and practiced in an intimate relation to violence (Mbembe, 2019). Describing modern democracy as ‘pro-slavery’, Mbembe (2019: 20) argues colonialism is the sediment on which democracy has been built, arguing the plantations in the Caribbean and Americas, the European colonies and democracy share a constitutive relationship of ‘repressed proximity and intimacy’; a matrix that is key for understanding the current global forms of violence that Giroux (2022a; 2022b) highlights in his diagnosis of our democratic crises (i.e. white supremacy, necropolitics). Even though democracy was built on forms of exclusion and oppression, it became a synonym for civilisation, and therefore essential to all nations, which legitimised the expropriation of land and destruction of livelihoods around the globe, during and beyond European colonialism (Mbembe, 2019). In turn, democracy was also deployed as a way to support decolonisation processes, which Bonilla (2015) and Mbembe (2021) argue included imposing a locus of sovereignty (the nation-state) and supporting members of the international elite to get to power, which ensured the continuation of colonial relations, albeit at a distance. International development initiatives have often been implicated in such transitions, ensuring the creation of hierarchies between former colonisers and colonies, based on discursive formations that constructed ‘developed’ and ‘underdeveloped’ nations, sustaining the economic dependency between them (e.g. Escobar, 1999; Rodney, 2018). In this context, education has at times been thought of as a tool for helping ‘developing’ countries become more democratic, through democratic education (see e.g. Harber and Mncube, 2012).

Shedding light on the circularity of the violence performed by democracy is helpful in challenging the Western teleological story of progress through democracy and / for development. Conceptualising democracy and violence as intimately entangled supports conversations that go beyond a dichotomy between democracy/violence or freedom/domination, which tend to lead to a negation of democracy or freedom when in the presence of violence or domination. An easy way to dismiss these entanglements would be to argue the history discussed above refers to a narrow, even erroneous, understanding of democracy, and that we need to think of democracy as ‘x’ (insert preferred definition). For example, Giroux (2022a) distinguishes ‘democratic values’ from racial injustices and loss of human rights. This distinction creates a distance between the lofty place of democracy and the systems of oppression ignited with colonialism, which we tend to position as a contradiction. Other scholars attempt similar distinctions by reframing the meaning of democracy or how/when it is expressed. For example, by making distinctions between thin (actions restricted to disaggregated practices such as voting) and strong democracy (actions based on a fuller range of participative action and dialogue) (Barber, 2004). Rockhill (2017: 77-78) summarises the extent of these attempts well, when he describes the numerous changes in understandings of democracy, ranging as:

“an interruption rather than a state of affairs, by way of a theoretical shift from being to event, from substance to act, from substantive to verb, from the state to political action, and more generally from a positive dialectic of synthesis to a negative dialectic of contradiction without end”.

But what possibilities are offered to development education when we take up democracy at face value, as a world-making idea and practice, that is both oppressive and liberating, rather than searching for its ‘best version’? Anker’s (2022) study of ugly freedoms is helpful for this endeavour.

Anker (2022) takes up the modern idea of freedom to mean a wide range of conceptualisations and expressions, by describing them as ugly. This aesthetic category is used because it elicits an affective response, of judgement and dissonance, that challenges assumptions of universal desirability. Without falling into the more common separations between freedom versus violence or domination, Anker (2022: 5) understands freedom as ‘both nondomination and domination, both worldmaking and world destruction’, because it would be ‘too reassuring to claim that these systems are only falsely justified as freedom’. In her study of ugly freedoms, Anker (2022: 38) traces the commodity of sugar to its colonial roots, linking ‘individual freedom to plantation mastery, self-rule to enslavement, and independence to environmental destruction’. By describing freedom(s) as ugly, Anker aims to bring to the fore the dissonance that emerges from a conceptualisation of uncoerced action that is often practiced as/through violence and subjugation, disrupting modern idealisations of freedom as inherently good and universally desirable. As Anker argues, the issue is not that normative versions are wrong, but that they miss the forms of domination present in freedoms’ wide range of expressions. Anker’s work offers an alternative reading that sees a more complex picture of freedom as attached to domination, rather than needing to be liberated from it, and supports a critical engagement with freedom that unsettles its assumed meaning.

I read the self-evidence of democracy as inherently good, desirable, and the only means for liberation, in line with Anker’s engagement with modern freedoms. Although Anker is speaking from a United States context, with a specific history and form of liberal democracy, we can arguably find this common assumption about democracy as the holy grail of modern societies across Euro-western contexts. These visions of democracy seem to step over the violent systems of oppression on which democracy has been built and (because of that) tends to reproduce. In this way, we might not see the multiple expressions of violence, inequality and marginalisation as un-democratic, or as being ‘far removed from democratic values’ (Giroux, 2022a: 96), but in an intimate relationship with democracy. It is essential, then, that we also see democracy as ugly, and bring it into development education, not as the answer, but as a problem that we must grapple with, if we mean to develop more productive engagements with global issues. What kind of development education can find not only a ‘new language for equating freedom and democracy’ (Giroux, 2022a: 103), but also interrogate the self-evidence of freedom and democracy, and engage with alternative histories and perspectives, so that it can think and experience them differently?

In describing freedom(s) as ugly, Anker (2022) performs a second conceptual move that is helpful for thinking about development education differently. In the second use of the term, she engages with practices that would be dismissed or rejected for being too ambivalent, compromised, or inconsequential. As Anker explains, ‘ugly freedom in this second valence does not require a virtuous actor, an upstanding citizen, or an ideal political subject explicitly yearning for liberty’ (2022: 14). These ugly freedoms are not righteous, celebrated actions, but instead emerge from ambivalent or trivial situations, and tend to take the ‘low road’ (Ibid: 17). They are also necessarily contextual and specific to the people enacting them, depending on the possibilities offered by a given moment. Anker draws on the television series The Wire (HBO, 2002) to identify some of these more subversive, morally compromised, forms of freedom that are carved within neoliberal dominance.

In her analysis of the series, Anker comes across practices of freedom that involve, for example, destroying public property and using low-level technology (as opposed to more developed forms) to flee police surveillance. Such practices challenge neoliberal discourse around technological development as essential in our lives and social relations. She also reads eye-rolling and collective boredom as performative acts, which, in the series, lead a group of teachers to stage a collective refusal of neoliberalism. In the scene analysed by Anker, teachers refuse to engage with a seminar where they are being ‘taught’ how to become better teachers, without any consideration of the cuts and community issues they are dealing with. The school in the series is also shown tinkering with statistical data, and this is also understood by Anker as an enactment of freedom, where teachers disinvest from externally imposed measures of neoliberal accountability and reinstate confidence in their professionalism and competence. In the context of international development and politics, we can also find examples of ugly freedoms that challenge modern understandings of democracy. Scholars in the field have put forward concepts such as post-development (e.g. Escobar, 2010) and degrowth (e.g. Abazeri, 2022), which challenge modern ideas of development and progress. The Zapatistas movement in Chiapas, enact alternative possibilities for expressing communal ways of being within, although incommensurable with, the nation-state (Mignolo, 2021). Although compelled to refer to democracy to explain their praxis, the Zapatistas movement is not built on European philosophical principles, drawing instead on Mayan cosmology (Mignolo, 2021). Similarly, Bonilla (2015) describes social movements that are often seen as ‘disappointing’, in Guadeloupe. These actions have sought a restructuring of the social, without calling for freedom from the French government. Describing them as non-sovereign, Bonilla (Ibid) argues these movements are a direct challenge to the normative Eurocentric idea that sovereignty defines a society's level of development. These are examples of possibilities for challenging and contesting, whilst working within, dominant structures. They identify ‘delicate shifts in the ways and forms of everyday life that challenge, even as they are unable to fully escape, the political and economic binds of modern life’ (Bonilla, 2015: 172-173).

This second understanding of freedom does not necessarily fit our modern conceptualisation, which tends to understand it as a consequence of just, pure, heroic acts that call for emancipation from domination (Anker, 2022). In this way, they can help us consider other possibilities for what development education might look like in practice, and challenge mainstream approaches, which might equate action with ‘doing’ (Pashby and Sund, 2020) and the lack of ‘doing’ with political apathy. This reductive set of possibilities for recognising ‘action’ in development education reinscribes the modern imaginary in the classroom and has been shown to foreclose ethical engagements with global issues (Pashby and Sund, 2020). It is important, then, that we hold different possibilities for what action might look like in development education, acknowledging that some expressions might not be visible, because of where we stand (i.e. in positions that are deeply rooted in Western modern ways of knowing and being in the world), but they warrant appreciation due to the opportunities they offer for delinking from Eurocentric ways of knowing, framed by teleological progress and invested in the need for certainties (e.g. Andreotti et al., 2015). For example, Pashby and Sund (2020) argue reflexivity is an important ‘action’ in and of itself, and an essential one for helping teachers and students stay within the morally ambiguous space we often find ourselves in, when (un)learning about global issues.

Democracy as a starting point for development education

Democracy has long been a taken for granted concept in modern conversations about education. These conversations tend to assume that a) democracy is inherently good and universally desirable; b) democracy is under attack; c) democratic education will support more developed and democratic societies. Starting with these premises will likely put us on a long travelled path of ever expanding conceptions of democracy and democratic/development education. But it will not allow us to notice how the path has been built on centuries of violent and oppressive practices that were legitimised and continue to be sustained by democracy. It is therefore necessary that we understand democracy as ugly: a problem, rather than the answer, for development education. Taken as a problem, democracy is a helpful tool with which to target the modern imaginary framing, prescribing, and thus limiting, education in general and development education in particular. Learning from enunciative positions inside/outside Eurocentric spaces, from places where democracy has been assumed and places where it has been imposed, is an important exercise in our efforts to dislodge democracy’s self-evidence and delink from the Eurocentric imaginary that bounds our ways of knowing and being. This article has drawn on Anker’s two-fold concept of ugly freedoms as a framework to support this effort, and complexify mainstream understandings of democracy.

Development education’s response to the current multiple global crises we are facing should indeed pay attention to knowledge production in the classroom (Giroux, 2022a; Giroux, 2022b), whilst centring the fact that critical thinking is always already framed by the dominant culture (Dreamson, 2018). This step is key, if we are to address the ways in which education reproduces colonial systems of oppression, and it requires that we critically interrogate and challenge concepts such as democracy, which seem to be constitutive of Eurocentric epistemology and, because of that, are assumed. Addressing Eurocentrism in the classroom is not necessarily a road towards moral relativism (see e.g. Oxley and Morris, 2013) or an endless pluralism (see e.g. Pashby, da Costa and Sund, 2020). Instead, it requires that we target and delink from Eurocentric onto-epistemological frames of reference, so that we can re-frame the ways in which international development issues get constructed and discussed in the classroom (see e.g. Pashby and Sund, 2020; Sund and Pashby, 2020); and that we do so in ways that retain the complexity, ambiguity and uncertainty inherent in this work (e.g. Amsler, 2010, Andreotti et al., 2018; Pashby and Sund, 2020). Taking up democracy as a problem for development education, an idea that can be interrogated in the compromised space of the classroom might help identify the Eurocentric tropes that this concept carries (i.e. the teleological development, heroic action, sovereign emancipation). This is a reflection that can be translated to development education and help us question our Eurocentric assumptions about development.

Anker’s second conception of ugly freedoms offers an alternative framework for thinking about development education practice, and reinforces the importance of acknowledging complicity in causing the issues we are trying to address (Andreotti, 2006), whilst disinvesting from our modern attachments to purity and certainties (Andreotti et al., 2018), which we tend to cling on when thinking about action. By acknowledging complicity and the complexity of the systems of oppression we are implicated in, we might recognise our morally ambiguous positions and (Pashby and Sund, 2020) move from a position of 'episteic certainty' to one of 'epistemic reflexivity' (Andreotti, 2016). Anker’s (2022) work also reminds us that we need to make peace with the ‘systems hacking’ approach identified by Andreotti and colleagues (2015). Systems hacking retains a concern with opening up spaces within schools for critical engagements with global issues in ways that address modernity’s violence and disinvest from the comforts it affords those of us in Euro-western contexts. This position within modern institutions, which we know have caused and continue to reproduce the very issues we are trying to address, as well as our own investments in modernity’s benefits (Stein et al., 2020), places us in a necessarily compromised position. However, understanding that freedom can be enacted within such morally ambivalent spaces, can be freeing in and of itself, and will help us think about development education in more ways than one - going beyond a focus on 'beating the system' (e.g. Girous, 2022a) or waiting for the system to 'beat itself' (see Andreotti et al., 2015).

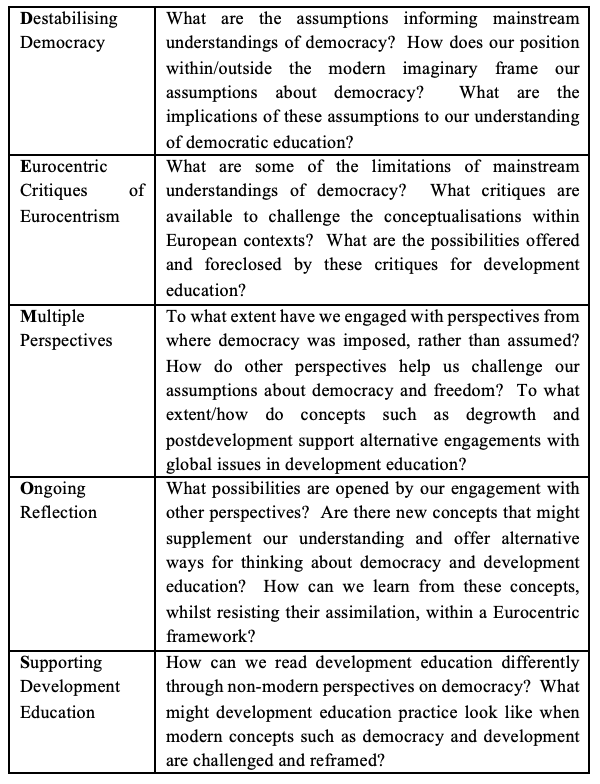

There is likely a wide range of ways in which we might consider taking on the learnings from Anker’s ugly freedoms in development education. Below, I suggest a performative tool that deconstructs part of democracy’s Greek roots (DEMOS) to elicit critical conversations within development education, where problematising democracy might be used as a starting point for conversations.

References

Abazeri, M (2022) ‘Decolonial feminisms and degrowth’, Futures, vol. 136, pp. 1-6.

Amsler, S (2010) ‘Bringing hope “to crisis”: Crisis thinking, ethical action and social change’ in S Skrimshire (ed.) Future Ethics: Climate Change and Apocalyptic Imagination. London: Continuum.

Andreotti, V (2006) ‘Soft Versus Critical Global Citizenship Education’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 3, Autumn, pp. 40-51.

Andreotti, V, Stein, S, Ahenakew, C and Hunt, D (2015) ‘Mapping interpretations of decolonisation in the context of higher education’, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, Vol. 4, 1, pp. 21-40.

Andreotti, V (2016) ‘Multi-layered Selves: Colonialism, Decolonization and Counter-Intuitive Learning Spaces’, Pedagogy, Otherwise, 10 December, available: https://www.artseverywhere.ca/multi-layered-selves/ (accessed 24 January 2023).

Andreotti, V, Stein, S, Sutherland, A, Pashby, K, Suša, R, Amsler, S, with the Gesturing Decolonial Futures Collective (2018) ‘Mobilising Different Conversations about Global Justice in Education: Toward Alternative Futures in Uncertain Times’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 26, Spring, pp. 9-41.

Anker, E R (2022) Ugly Freedoms, London: Duke University Press.

Barber, B (2004) Strong Democracy: Participatory Politics for a New Age. Berkley: University of California Press.

Bonilla, Y (2015) Non-sovereign Futures: French Caribbean Politics in the Wake of Disenchantment, London: University of Chicago Press.

Brooks H, Ngwan T, Runciman C (2020) ‘Decolonizing and re-theorizing the meaning of democracy: A South African perspective’, The Sociological Review, vol. 68, 1, pp. 17-31.

Dreamson, N (2018) ‘Culturally inclusive global citizenship education: metaphysical and non-western approaches’, Multicultural Education Review, vol. 10, 2, pp. 75–93.

Escobar, A (1999) Encountering Development, Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Escobar, A (2010) ‘Latin America at a Crossroads: alternative modernisitaions, post-liberalism, or post-develpoment?’, Cultural Studies, vol. 24, 1, pp. 1-65.

Giroux, H (2022a) ‘The Politics of Ethicide in an Age of Counter-Revolution’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, vol. 34, Spring, pp. 95-110.

Giroux, H (2022b) ‘Resisting Fascism and Winning the Education Wars: How we can Meet the Challenge’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, vol. 35, Autumn, pp. 111-126.

Held, D (2006) Models of Democracy (3rd Edition), Cambridge: Polity Press.

Harber, C and Mncube, V (2012) Education, Democracy and Development: Does Education Contribute to Democratisation in Developing Countries?, Southampton: Symposium Books.

HBO (2002) The Wire, available: https://www.hbo.com/the-wire (accessed 20 December 2022).

Mbembe, A (2019) Necropolitics, London: Duke University Press.

Mbembe, A (2021) Out of the Dark Night: Essays on Decolonization, New York: Columbia University Press.

Mignolo, W (2011) The Dark Side of Western Modernity, London: Duke University Press.

Mignolo, W (2018) ‘The Conceptual Triad: Modernity/Coloniality/Decoloniality’ in W D Mignolo and C E Walsh (eds.) On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis, London: Duke University Press.

Mignolo, W (2021) The Politics of Decolonial Investigations. London: Duke University Press.

Oxley, L and P Morris (2013) ‘Global citizenship: A typology for distinguishing its multiple conceptions’, British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol. 61, 3, pp. 301-325.

Pashby, K, da Costa, M, Stein, S and Andreotti, V (2020) ‘A meta-review of typologies of global citizenship education’, Comparative Education, Vol. 56, 2, pp. 144-164.

Pashby, K and Sund, L (2020) ‘Decolonial options and challenges for ethical global issues pedagogy in Northern Europe secondary classrooms’, Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education, Vol. 4, 1, pp. 66-83.

Pashby, K, da Costa, M and Sund, L (2020) ‘Pluriversal possibilities and challenges for Global Education in Northern Europe’, Journal of Social Science Education, Vol. 19, 4, pp. 45-62.

Rockhill, G (2017) Counter-History of the Present: Untimely Interrogations into Globalisation, Technology, Democracy, London: Duke University Press.

Rodney, W (2018) How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, London: Verso.

Sant, E (2021) Political Education in Times of Populism: Towards a Radical Democratic Education, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Santos, B S (2016) Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide, Oxon: Routledge.

Scott, D (2004) Conscripts of Modernity: The Tragedy of Colonial Enlightenment, London: Duke University Press.

Stein, S (2018) ‘Rethinking Critical Approaches to Global and Development Education’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 27, Autumn, pp. 1-13.

Stein, S, Andreotti, V, Suša, R, Ahenakew, C and Čajková, T (2020) ‘From “education for sustainable development” to “education for the end of the world as we know it”’, Educational Philosophy and Theory, Vol. 54, 3, pp. 1-14.

Sund, L and Pashby, K (2020) ‘Delinking global issues in northern Europe classrooms’, The Journal of Environmental Education, Vol. 51, 20, pp. 156-170.

Trouillot, M-R (2009) ‘North Atlantic Universals: Analytical Fictions, 1492-1945’, in S Dube (ed.) Enchantments of Modernity: Empire, Nation, Globalisation, London: Routledge.

Walsh, C E and Mignolo, W D (2018) ‘Introduction’ in W D Mignolo and C E Walsh (eds.) On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis, London: Duke University Press.

Zembylas, M (2022) ‘Decolonising and re-theorising radical democratic education: Toward a politics and practice of refusal’, Power and Education, Vol. 14, 2, pp. 157-171.

Marta da Costa is a lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University, where she teaches in the BA (Hons) Education programme and is a member of the Education and Social Research Institute (ESRI). Marta’s research focuses on decolonial approaches to Global Citizenship Education (GCE) and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) research and practice.