“We Must Dissent”: How a Belfast Urban Community is Building Critical Consciousness for Spatial Justice

Development Education and Democracy

Abstract: At a time of perceived permacrisis across the UK and Ireland, certain places and people are being further subjected to the unequal and unjust distribution of resources and opportunities. Inequality has a geography and shocks like the ‘cost-of-living crisis’ have been felt more deeply in the so-called ‘left behind’ places that already experience lower standards of living and services. Top-down approaches to community renewal have had mixed results, with evaluations often citing a lack of contextual relevance, which has led to growing cynicism within the community sector. For that reason, there is a greater sense of urgency to think critically about place-based inequalities and to challenge the dominant assumptions, systems, and structures that reinforce them.

In this article we present the example of a working-class community in urban Belfast, pursuing spatial justice by employing their own rights-based framework for renewal. We offer a critique of this framework through the lens of critical pedagogy, highlighting its basis in praxis, and describe how participative methods have been used to develop the community’s critical consciousness.

Key words: Spatial Justice; Critical Pedagogy; Place; Community; Education.

At a time of perceived permacrisis certain places and people are being further subjected to the unequal and unjust distribution of resources and opportunities (Bell, 2019; Patel et al, 2020; Leyshon, 2021; Rodrigues and Quinio, 2022). Inequality has a geography and people within these places, where less favourable outcomes tend to concentrate, experience lower standards of living and services. As this socio-spatial character becomes more pronounced there is a greater sense of urgency to think critically about place-based inequalities and to challenge the dominant assumptions, systems, and structures that reinforce them (Amin, 2022).

Policymaking at national and international levels has become increasingly informed by a place-based agenda (McCann, 2019). Yet, the outworkings of this often fail to deliver the structures and practices necessary for an inclusive and democratic process of change. In this context, there is a growing need to capture and reproduce grassroots pedagogies that effectively support the deep transition of underserved communities - those that help to develop resilience against crises and respond to the intractable challenges of place-based inequalities, e.g., local poverty reduction (Pinoncely, 2016) - and equip them to become agents of their own socio-spatial transformation.

This article focuses on how critical pedagogy has influenced the grassroots regeneration efforts of an urban, working-class community in Belfast, called the Market. We offer an account of residents leading their own learning and making meaningful connections to the world around them by turning the community itself into a site of education, constructive action, and conscientisation. Their collective praxis has culminated in a rights-based framework for community renewal called We Must Dissent (Hargey, 2019). Using this framework, the community has been able to grow capacity, mobilise local knowledge, build an evidence-base, and empower local voices, leading to a process of transformation and a legitimate plan for equitable change.

The context of space-blind policy

In February 2022, the UK government published its Levelling Up white paper framing the transformation of places and addressing uneven economic development. It proposed maximising the power of left behind places to level up, in which opportunity is conceptualised as a driver for national growth with the potential for increasing living standards and remedying regional, place-based inequalities (Tomaney and Pike, 2020; Leyshon, 2021). The language and intentions echo previous neoliberal urban policy initiatives and there is a risk that it will repeat the same failures (see Drozdz, 2014). It conceives an economic solution that targets the symptoms of an unjust, unequal society, rather than truly empowering local communities to address the underlying causes of their hardship. The Government’s interpretation of place-based inequality misjudges its complexity and fails to recognise that issues like poverty and social exclusion cannot be fully understood unless located within its local context (Pringle, Walsh, and Hennessy, 1999). In fact, the overall structure for decision-making (as described in the White Paper) is unsympathetic to this.

As the draft Levelling-up and Regeneration Bill now makes its passage through scrutiny, there is an evident lack of representation for left-behind places in decision-making - symptomatic of the ‘hollowed out’ infrastructure for local democracy (Telford and Wistow, 2022). In the first instance, the broader policy regime is managed and controlled by Whitehall with little influence from the devolved regions, and secondly, it claims to empower local businesses and leaders as decision-makers in local areas. This removal of the deliberative process from its social, historical, geographical, cultural, political, and administrative context is problematic, particularly in the devolved regions. In Northern Ireland (NI), for example, ‘place’ is still heavily politicised along ethnonational lines and often characterised by patterns of segregated living and contested spaces - a socio-spatial reality that Levelling Up fails to acknowledge. Investment in infrastructure will not address the complexity of this issue, particularly if it excludes local problem owners from the development of solutions. In fact, as the Conservatives incorporate planning reforms into the Bill’s language, morphing it into a ‘planning Bill with a bit of levelling-up wraparound’ (Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Committee, 2022: Q167, para 1), there is a danger of reinforcing processes of socio-spatial segregation (Alonso and Hita, 2013) and limiting the democratic spaces for local communities to engage with proposals.

It is claimed that neoliberal ‘space-blind’ policy has failed and must give way to place-based policymaking that empowers local communities and destabilises the status quo, to allow them to escape from under-development traps (Barca, 2019). Levelling Up does not go far enough to repair the socio-spatial injustices experienced by ‘left-behind’ places due to austerity. It is an example of the neoliberal turn in the global political economy that has also seen a trend in community development away from a model of organising to one of service provision, blunting its engagement with critical pedagogy in the process (Baker and McLaughlin, 2010; Ledwith, 2007; Legg, 2018). At its best, community work is practiced at educational sites of resistance and the interfaces between oppressive elements (Ledwith, 2001; Mayo, 1999). However, there are concerns that it risks being removed from its grassroots, participatory context thereby stripping it of its empowering and emancipatory purpose (Kenny, 2019). Regaining the radical edge of the field is a key challenge (Ledwith, 2020). Communities at risk of socio-spatial segregation must be empowered to push back against these trends, or risk becoming disconnected from their places.

Critical pedagogy and place

Critical pedagogy provides a framework for social transformation through education, in which learners are encouraged to examine the issues and structures of power and oppression and engage in the act of conscientisation: ‘learning to perceive social, political, and economic contradictions, and to take action against the oppressive elements of reality’ (Freire, 1970/2017: 9). Critical pedagogies are claimed to be inherently pedagogies of place (McClaren and Giroux, 1990: 263). They recognise that the spatial aspects of social experience are critical to understanding the processes of oppression (Pringle, Walsh, and Hennessy, 1999). Individuals are perceived by Freire as rooted in temporal-spatial conditions that ‘mark them’, which he expresses as situationality (1970/2017: 82). However, the prominence critical pedagogy gives to place varies by tradition and application.

One of these traditions is critical pedagogy of place, which has been described as an attempt to establish an educational theory responsive to the cultural and ecological politics of place (Greenwood, 2013). It is a pedagogy informed by the ethics of environmentalism and eco-justice in the context of economic overdevelopment, yet the way in which it draws out socio-spatial experience has merit beyond these foci. The framework augments Freire’s situationality by bisecting it into corresponding spatial dimensions referred to as decolonisation and reinhabitation (Greunewald, 2003). Both are conceived as broad educational goals concerned with how geographical conditions shape people and vice versa. In short, critical pedagogy of place aims to:

“…identify, recover, and create material spaces and places that teach us how to live well in our total environments (reinhabitation); and (b) identify and change ways of thinking that injure and exploit other people and places (decolonisation)” (Ibid: 9).

The approach is useful for enabling communities to decode and read places in the world as political texts, so that they may then decolonise and reinhabit their ‘storied places’ through reflection and praxis (Johnson, 2012). Similarly, critical spatial practice, described as a form of civic pedagogy, adopts a situated learning approach that uses the environment as a resource to make people aware, skilled, and prepared to act over their surroundings, reinforcing a form of local active citizenship (Martinez, 2019).

Critical pedagogy and its place-conscious variations offer a practical way for the communities characterised as left-behind to resist neoliberal policies that diminish the control and ownership of their spatial contexts. As an example of this, we turn our attention to the case of the Market community in Belfast, where place-conscious pedagogy has influenced a praxis for spatial justice. In keeping with the principles of critical pedagogy, the subsequent account of their transformative process is co-authored with a leading project worker from the community.

A reflection upon situationality: The Market

The Market is one of the oldest working-class communities in Belfast, situated directly within its urban precinct, to the south-east of Belfast City Hall. It takes its name from the fourteen commercial markets - fish, fruit, cattle etc - which once dotted the area, with St George’s Market being the last remaining. In tandem with the markets, there was a range of industries including bakeries, abattoirs, chemical works, iron foundries, as well as dozens of shops and public houses. The area, historically, was built on a grid pattern and completely integrated into Belfast city centre. Although people were never wealthy, they never went hungry.

The complexion of the area began to change in the late 1960’s with a combination of planning, infrastructural, and economic decisions leading the area to become deindustrialised and badly impacted by road traffic. To compound matters, long overdue housing redevelopment in the 1970’s and 1980’s was informed by the euphemistically termed ‘defensive planning’ policies, which erased the historic grid pattern and led to a further marginalisation of the community. These urban development practices carried over into the Peace Process, and while over one billion pounds was invested by the Laganside Corporation into the vacant waterfront surrounding the Market, the area was segregated by gates, walls and fences that amounted to an economic interface that cut the community off from the peace dividend surrounding it. The conflict has been a significant factor in the trajectory and shape of the community and despite relative peace for a generation, the negative impacts of its legacy on health, education, and employment remain. In this time, the Market community has seen its population drop from approximately 6,000 people before redevelopment, to 2,500 at present. The community’s physical size was also greatly reduced and coupled with the barriers, road network, and disinvestment, a strong sense prevailed in the community that it was slowly being squeezed out of the city centre.

The Market Development Association (MDA) was established in December 1995, aiming to promote the well-being of all residents and develop the community into one where people want to live, work, and socialise. Its ongoing function is to advocate on behalf of the Market community on socio-economic issues, by adopting a community development approach. In 2010, the MDA drafted a wider regeneration plan for the area. The central theme of this plan was connectivity. Primarily this meant overcoming the historic legacy of physical disconnection that resulted from the unrelenting redevelopment processes and redesigns, but also reconnecting the community back to the wider economic, social, and cultural life of the city. The flagship project of this Regeneration Plan was the conversion of local tunnels into a series of social enterprise business units, which would provide employment, social, educational, and cultural spaces for both the community and wider area.

From 2010 onwards the area was faced with a number of existential challenges, ranging from the ongoing austerity policies that set the general context, to planning decisions on specific sites within the community. The nadir of this time was the assassination of the MDA’s leading strategic regeneration worker in 2015, who had overseen its key capital projects, as well as education projects in the area, and provided a constant support to younger residents in organising their own initiatives. This loss had a harrowing impact on the community and was followed closely by the disappointing approval of further commercial developments on sites presumed for community use. The feeling at this time was that the area’s viability was being rapidly diminished, as the challenges the community faced intensified by the day. At this time, conversations were being had about the way forward, what constituted community development and the need for a renewed focus on critical education.

The pedagogy of ‘We Must Dissent’

The limit-acts of the Market - seeing and acting beyond the limits of their situation, to overcome their obstacle(s) - have evolved from a much older working-class organising tradition of worker inquiry (Hoffman, 2019), drawing upon the experiences of activism within the community, from the Republican and Civil Rights Movements, as well as community development practices. They mean to educate the community in the literacy of struggle (cultural and political), intent on raising individual and collective consciousness, whilst also generating spaces for action. The community itself is the primary site for this, where their physical world and social history inform a broad programme of popular place-conscious education. In collaboration with other partners, the MDA has codesigned and facilitated several learning projects, including the Market 1916 Centenary Project, Social Education Project, Guerrilla Filmmaking course, research workshops, and social history project - ranging from traditional lectures to discussions, book clubs, and the sharing of oral histories through storytelling, workshops, and performances. Collectively these have formed a curriculum in which the socio-spatial context of the Market community is located at the centre.

Participation in community-led research is a critical aspect of their pedagogy, which enables residents to decode their collective experience and generate themes that inform a shared praxis. Community surveys are co-designed by resident-activists with the intention of capturing data on their collective experience. The results are then analysed in a series of workshops with residents, to prioritise the key issues and agree human rights indicators against which progress can be measured. This process is consciously influenced by critical pedagogy and the concept of generative themes, which set the boundary curtailing the residents’ quality of life, while also allowing them to conceptualise it as a barrier to overcome, by linking their experiences to broader civic, national, regional, continental, and global trends (Freire, 1970/2017: 83-85). Survey results, workshop feedback, and human rights indicators are subsequently compiled and synthesised with the spatial, economic, and social history of the community to contextualise the issues in a report - an artefact of the community’s struggle. The community-led research and report for We Must Dissent (WMD) identified Overdevelopment, Road Safety, Housing, Health, Education, and Work as issues that required community action (Hargey, 2019). While the WMD report endeavoured to document these thematic issues, it also sought to avoid a purely deficit-based approach to community life - the evidence gathered suggested a strong sense of community pride and an eagerness on the part of residents to become more active. The report has since served as a rallying point for community mobilisation, allowing residents to engage in the political, legal, and planning processes in a way that has become increasingly uncommon.

The survey itself coincided with the launch of the ‘Save the Market’ campaign, a residents’ grassroots network for highlighting their concerns with planning decisions and to raise awareness via media campaigns, street actions, resident mobilisations, and protests, along with political, statutory, and legal engagement. This has been ongoing since 2017 and has had some notable successes in the Judicial Review Court and at Belfast City Council’s Planning Committee, along with its various sub-campaigns. In essence residents are fighting for the right to have an equal say in the uses and shaping of their urban environment on the same basis as the private and public sector, which has been characterised as the ‘right to the city’ (Harvey, 2013). This form of participative method is complemented by specific action groups, aligned to each of the themes identified within the WMD report. The purpose of these groups, comprised of residents, local stakeholders, and academic experts, is to consider a strategic response to each theme and co-design follow up programmes. Both the campaigns and actions groups are mutually reinforcing and together offer opportunities for dialogics, reflection, and action.

The challenge to this pedagogical approach has been a lack of local capacity, leading to research bottlenecking. To address this by building research capacity, the MDA has established a unique Higher Education partnership with nearby initiative Queen’s Communities and Place (QCAP) (Higgins et al., 2022). The MDA and QCAP have a strong working relationship across co-produced work strands - broadly focusing on education, health, and community wealth - having signed a social charter outlining the University’s commitment to the Market community. The purpose of this partnership is to confront the contradictions of their socio-spatial experience through place-based research and enhance the community as a site of pedagogy, thus enabling critical agents for democratic change. In addition to this, it is seen as a way of disrupting hierarchies of knowledge by elevating local voices in the process of inquiry.

As anchor institutions, universities have the capacity to support the deep transition of disadvantaged communities, so they can develop resilience against exogenous shocks and respond to more intractable challenges. They are well-placed to link academic knowledge with local problem owners (Benneworth, 2017) and lead social innovation ecosystems to address local challenges (Howaldt and Schwarz, 2010; Baturina, 2022). Universities can provide spaces and intellectual resources to complement and build on the enormous cultural and social capital of communities (Tandon et al., 2017). Yet, this potential of anchor institutions is not easily realised. If universities are to proactively shape the local conditions for positive change, then a different type of community-university partnership is required. One that is driven by social and civic responsibility, with a clear transformative mission (Aranguren, Canto-Farachala, and Wilson, 2021). Research must be integrated with community engagement to co-produce socially relevant knowledge, by bringing those from the academic ecosystem together with community members in ways that raise local voice (Tandon, 2014).

A place-conscious model of praxis

We Must Dissent (Hargey, 2019) is an example of a working-class community equipping themselves with the types of literacy and tools required to identify, address, and confront the contradictions of their socio-spatial experience. It is a model of place-conscious praxis and grassroots transformation, with the community at its core, in pursuit of spatial justice and the betterment of socio-economic outcomes.

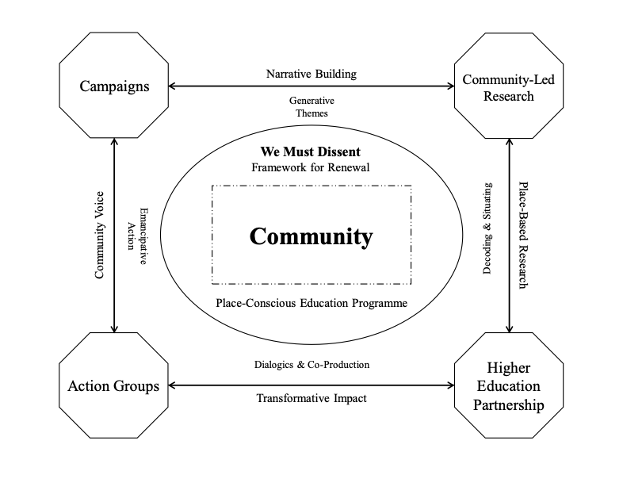

Figure 1 We Must Dissent Model of Place-Conscious Praxis

Each of the community’s activities - community-led research, campaigns, action groups, and higher education partnership - represent four mutually reinforcing pillars of action (illustrated in Figure 1). Individually the pillars are limited in their transformative potential. It is only when combined and underpinned by a programme of popular education do they start to generate the benefits of praxis. They establish the community’s praxis by combining: (i) mechanisms for reflection that establish the complexity of their contradictions; (ii) a means to co-produce evidence that contextualises their socio-spatial reality; and (iii) the apparatus to act upon objective reality. The product is an effective framework for countering dominant narratives, perceptions, and established facts relating to the community. It permits people to contextualise their lives within a broader social totality, rather than individualised misfortunes, looking at the economic forces impacting them within this context. A resident who is first equipped for ‘struggle’ through participation in the place-conscious education programme, will then have legitimate mechanisms to express their disaffection through the pillars of action. It also sets targets for community renewal in its true socio-spatial context, which residents can champion through collective ownership, in pursuit of equitable change.

The application of this model, through praxis, has been an effective way for the community to re-establish a connection to a world and reality of their making. They have managed to secure multiple sites for social housing; planning and funding arrangements are progressing for the community’s capital projects; and the engaged partnership with QCAP is building capacity for place-based research and regeneration. However, the community’s history is still being made - the work is ongoing, and its ultimate efficacy remains to be seen. The WMD report was never intended to be the final word on the community’s issues, more like a milestone in an ongoing process. The Market’s praxis is now being ‘made and remade’, as the context and residents’ priorities change (Freire, 1970/2017: 22). Like a cycle of inquiry, the reflections made during the WMD are now feeding into new deeper processes in partnership with QCAP. Moreover, there is merit in the Market connecting to other communities facing similar issues and sharing their praxis, as it will further bolster the discovery of their own struggle. Once the community has seen a positive change to their reality, their pedagogy moves into Freire’s second stage and ‘pedagogy for all people in the process of permanent liberation’ (1970/2017: 28). This perspective is also informed by Wenger’s Communities of Practice (1998), in which strong inward facing boundaries are initially preferrable to establish solidarity and shared purpose, but eventually to renew practices and improve outcomes, these boundaries must become porous.

The community’s pedagogy is informed by resistance and place, supported by a place-conscious education programme that initiated the creation of conditions for residents to critique their history of colonialisation and act upon economic dispossession. Through its various education programmes, campaigns and the WMD report, the Market community has sought spatial justice, and to open the process to as many voices within the community as possible. The report was designed in such a way as to allow any resident, no matter their educational level, to pick it up, engage with the themes most pertinent to them, and to gain some level of understanding of that issue from a historical, socio-economic, and environmental context, as well as the international, European, and regional human rights frameworks relevant to these themes. It also links all these issues together in a way that draws attention to the wider historical processes that now manifest as homelessness, unemployment, or addiction.

We argue that a recognition of ‘place’ within praxis is necessary to fully achieve conscientisation. The Market is a community that perceives themselves as having been historically and presently colonised and disconnected from the city. For that reason, connections to their heritage, history, and place are particularly important to their identity as a working-class community. By understanding how their community came to be, their belief is that they’ll be better able to deal with the traumas and manifestations of colonisation. Their liberation comes from building critical awareness of this reality and drawing out the contradictions of their socio-spatial experience through praxis and recognition of the necessity to fight. This resonates with critical pedagogy of place - decolonisation and re-inhabitation. You cannot understand a person, their situation, nor experience if you separate it from their world. Peoples’ social networks, culture, history, and politics are tied to places. The spatial as Freire sees it is not only physical, but historical. Places of meaning contribute to an individual’s sense of self and being. It then follows that as communities lose control of their physical surroundings, seeing the area decay or lose it to overdevelopment, they become less human in the Freirean sense. Genuine place-based approaches aim to restore communities, which in turn aims to restore the people. Where residents are separate from their world, place-based approaches strive to re-situate them and inspire reconnection with place, pride, and hope - removing socio-spatial obstacles to their liberation.

References

Alonso, C H and Hita, L S (2013) ‘Socio-spatial inequality and violence’, Sociology Mind, 3(04), p.298.

Amin, A (2022) ‘Communities, places and inequality: a reflection’, IFS Deaton Review of Inequalities, 28 May, available: https://ifs.org.uk/inequality/communities-places-and-inequality-a-reflection (accessed 22 December 2022).

Aranguren, M J, Canto-Farachala, P and Wilson, J R (2021) ‘Transformative academic institutions: An experimental framework for understanding regional impacts of research’, Research Evaluation, 30(2), pp. 191-200.

Baker, S and McLaughlin, G (2010) The Propaganda of Peace: The Role of Media and Culture in the Northern Ireland Peace Process, Bristol: Intellect.

Barca, F (2019) ‘Place-Based Policy and Politics’, Renewal: a Journal of Social Democracy, 27(1), pp. 84-95.

Baturina, D (2022) ‘Pathways towards Enhancing HEI’s Role in the Local Social İnnovation Ecosystem’, Social Innovation in Higher Education, p. 37.

Bell, K (2019) Working-class Environmentalism: An agenda for a just and fair transition to sustainability, Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

Benneworth, P (2017) ‘Global Knowledge and Responsible Research’ in Global University Network for Innovation (eds) Higher Education in the World 6. Towards a Socially Responsible University: Balancing the Global with the Local, pp. 249–59. Girona: GUNI.

Drozdz, M (2014) ‘Spatial inequalities, “neoliberal” urban policy and the geography of injustice in London, Justice Spatiale-Spatial justice, 6.

Freire, P (1970/2017) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, London: Penguin Classics.

Greenwood, D A (2013) ‘A critical theory of place-conscious education’ in R B Stevenson, M Brody, J Dillon, and A E J Wals (eds) International Handbook of Research on Environmental Education, pp. 93-100, New York: Routledge.

Gruenewald, D A (2003) ‘The Best of Both Worlds: A Critical Pedagogy of Place’, Educational Researcher, 32(4), 3–12.

Hargey, F (2019) We Must Dissent: A Framework for Community Renewal, Belfast: Market Development Association.

Harvey, D (2013) Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution, London: Verso.

Higgins, K, Murtagh, B, Gallagher, T, Grounds, A, Robinson, G, Loudon, E, Duffy,G, Hargey, F, Brady, and Morse, A (2022) [Online] ‘Queen’s Communities and Place; Supporting places and community through engagement research and innovation’, Belfast: Queen’s University Belfast, available: https://www.qub.ac.uk/sites/qcap/about-us/QCAPApproach (accessed 17 February 2023).

HM Government (2022) Levelling Up the United Kingdom, London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Hoffman, M (2019) Militant Acts: The Role of Investigations in Radical Political Struggles, New York: SUNY.

Howaldt, J and Schwarz, M (2010) Social Innovation: Concepts, Research Fields and International Trends, Social Research Centre Dortmund, ZWE of the TU Dortmund.

Johnson, J T (2012) ‘Place-based learning and knowing: Critical pedagogies grounded in Indigeneity’, GeoJournal, 77(6), pp. 829-836.

Kenny, S (2019) ‘Framing community development’, Community Development Journal, 54(1), pp.152-157.

Ledwith, M (2001) ‘Community work as critical pedagogy: re‐envisioning Freire and Gramsci’, Community Development Journal, 36(3), pp.171-182.

Ledwith, M (2007) ‘Community Development: Reclaiming the Radical Agenda’, Infed.org, available: https://infed.org/mobi/reclaiming-the-radical-agenda-a-critical-approach-to-community-development/ (accessed 22 December 2022).

Ledwith, M (2020) Community Development: A Critical Approach, Bristol: Policy Press.

Legg, G (2018) Northern Ireland and the Politics of Boredom: Conflict, Capital and Culture, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Levelling Up, Housing and Communities Committee (2022), Oral evidence: Levelling-up and Regeneration Bill, HC 309, 18 July 2022, available: https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/10617/pdf/ (accessed 22 December 2022).

Leyshon, A (2021) ‘Economic geography I: Uneven development, “left behind places” and “levelling up” in a time of crisis’, Progress in Human Geography, 45(6), pp. 1678–1691.

McCann, P (2019) UK Research and Innovation: A Place-Based Shift?, University of Sheffield Management School, University of Sheffield.

McLaren, P L and Giroux, H A (1990) ‘Critical pedagogy and rural education: A challenge from Poland’, Peabody Journal of Education, 67(4), pp. 154-165.

Martinez, S P (2019) ‘Civic Pedagogy, learning as critical spatial practice’, Critical Spatial Practice, available: https://criticalspatialpractice.co.uk/civic-pedagogy-learning-as-critical-spatial-practice-2019/ (accessed 22 December 2022).

Mayo, P (1999) Gramsci, Freire, and Adult Education: Possibilities for Transformative Action, London: Zed.

Patel, J A, Nielsen, F, Badiani, A A, Assi, S, Unadkat, V A, Patel, B, Ravindrane, R and Wardle, H (2020) ‘Poverty, inequality, and COVID-19: the forgotten vulnerable’, Public Health, 183, pp. 110–111.

Pinoncely, V (2016) Poverty, place, and inequality: why place-based approaches are key to tackling poverty and inequality, London: RTPI.

Pringle, D G, Walsh, J and Hennessy, M (eds.) (1999) Poor People, Poor Places: A Geography of Poverty and Deprivation in Ireland, Dublin: Oak Tree Press.

Rodrigues, G and Quinio, V (2022) Out of Pocket: The places at the sharp end of the cost-of-living crisis, London: Centre for Cities, July, available: https://www.centreforcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Out-of-pocket.pdf (accessed 22 December 2022).

Tandon, R (2014) Knowledge Democracy: Reclaiming Voices for All, Paris: UNESCO, available: http://unescochair-cbrsr.org/unesco/pdf/Lecture_at_Univ_Cape_Town-August%20-2014.pdf (accessed 22 December 2022).

Tandon, R, Singh, W, Clover, D and Hall, B (2017) ‘Knowledge Democracy and Excellence in Engagement’, IDS Bulletin, 47(6), pp. 19–35.

Telford, L and Wistow, J (2022) ‘The Levelling Up Agenda’ in L Telford and J Wistow (eds.) Levelling Up the UK Economy, pp. 43-67, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tomaney, J and Pike, A (2020) ‘Levelling up?’, The Political Quarterly, 91(1), pp. 43–48.

Wenger, E (1998) Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Gareth Robinson is a Research Fellow at Queen’s University Belfast with a background in education in divided societies, school exclusion, school improvement, and education network development and analytics. He leads a work strand for Queen’s Communities and Place (QCAP), which explores the relationship between working-class communities and different facets of the knowledge economy concept: education, work, and innovation. His role with local community partners focuses on co-creating educational, research, and innovation opportunities to promote a more inclusive knowledge economy and to empower local working-class communities with increasing involvement in knowledge processes.

Fionntán Hargey is project worker on the Market Development Association’s (MDA) Community Transformation Initiative, leading on community engagement and organising, training, education, and economic development, including the Market Tunnels Project, Backpacker Hostel, Heritage Hub/Tenement Museum. He holds a degree in Politics (BSc) from Ulster University and an MA in Violence, Terrorism and Security from Queen’s University, Belfast (QUB). He leads on the MDA’s community engagement programmes and was the author of their report ‘We Must Dissent: A Framework for Community Renewal’. As well as his work at the MDA, he is vice-chair of the Pangur Bán Literary and Cultural Society and series editor of ‘The Market: A People’s History’ series of local historical publications. He previously served as the community co-investigator on the Creatively Connecting Civil Rights project at QUB.

Kathryn Higgins is the Director of the cross-Faculty, Queen’s Communities and Place Initiative, and professor of Social Science and Health in the School of Social Science Education and Social Work (SSESW), Queen’s University Belfast. Kathryn is an experienced research leader having previously led the Centre for Evidence and Social Innovation and the Institute for Child Care Research. Kathryn has an established research reputation in the areas of substance use and addictive behaviour and has also been active in the field of programme evaluation/implementation science. She continues to lead the now eighteen-year longitudinal study, known as the Belfast Youth Development Study, which has acted as a focal point for collaborations with external partners and for new, policy-led research. She has developed a cadre of work for more than ten years on Public Engagement Programme evaluation and implementation Science, evaluating interventions designed to improve child and adolescent development. These include RCTs of school- and community-based interventions. Her scholarly contributions have examined the policy and evidence base for interventions including substance misuse, mental health, alcohol prevention and the mechanisms for implementing evidence-based practice and policy more generally.