Teaching Macroeconomics and Political Science in Higher Education Using the Sustainable Development Goals

Development Education and Democracy

Abstract: This article reflects on the outcomes of a three-year teaching innovation project in which Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDGs) content was integrated into a traditional macroeconomics syllabus, and the subjects of Global Governance and Comparative Politics. The project provided training to practising university lecturers on development education and global citizenship education. By including the SDGs in teaching, the effects that certain economic and political decisions can generate in social, environmental and economic terms could be analysed. Under a humanistic approach, some economic and social trends are examined and valued considering the secondary effects that these actions produce, including generating poverty and social injustice.

The order and structure of the SDGs offer a conceptual framework that has facilitated critical analysis and understanding of the causes of inequality. In this regard, although the SDGs can be criticised as not being an effective instrument to achieve the goals for which they are designed, they are a useful reference for undergraduates and an efficient teaching resource to simultaneously comply with the delivery of subject content and introduction of development education. This teaching experience allows us to extract various reflections on the results obtained, some of which refer to the teaching activities carried out, and others on university students’ perceptions monitored using a survey.

The project improved the training of the participating university lecturers, who acquired greater knowledge, skills and enhanced their teaching practice. The project demonstrated the need of the university to enhance support for sustainability, involving the entire educational community and coordinating planning that contributes to the development of sustainable academic and professional capacities.

Key words: Development Education; Global Citizenship Education; Higher Level Education; Sustainable Development Goals; Economics; Political Science.

Introduction

For decades, international initiatives have been in place for universities to enhance development education and global citizenship education (DEGCE) by integrating training in economic, social and environmental sustainability into university curricula. Key reference documents, such as the guide Getting Started with the SDGs in Universities (Kestin et al., 2017), give universities a leading role in achieving a culture of sustainability. As such, universities are recognised as institutions dedicated to education, research, and the creation and transmission of knowledge, which contributes directly to providing agents of change and shaping more sustainable societies.

However, recent research, such as that of Valderrama-Hernández et al. (2020), indicates that, in the case of Spain, there is still much work to be done despite advances. Accordingly, the rectors, the highest authorities representing Spanish universities, recommended incorporating transversal competences into the curricula for sustainability in university education. This is reflected in the document approved by the Conference of Rectors of Spanish Universities which includes the following skills:

- “Competence in the critical contextualisation of knowledge, through the linking of social, economic and environmental issues on a local and/or global level.

- Competence in the sustainable use of resources and in the prevention of negative impacts on the natural and social environments.

- Competence to participate in community processes that promote sustainability.

- Competence to apply ethical principles related to sustainability values in personal and professional behaviour” (CADEP-CRUE, 2012: 7).

On the one hand, it can be seen that more work needs to be done to introduce these contents at the university level. On the other hand, it is becoming increasingly common to introduce, even unknowingly, DEGCE topics that reinforce various values in formal education, specifically under the consolidated approach of education for sustainable development (ESD), which according to UNESCO ‘Empowers learners to take informed decisions and responsible actions for environmental integrity, economic viability and a just society for present and future generations’ (2017: 7).

DEGCE is delivered at the university level but needs more impetus. There are many reasons to justify the implementation of DEGCE in our university subjects, including SDG 4.7 which has the following aim:

“By 2030 ensure all learners acquire knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including among others through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship, and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development” (United Nations General Assembly, 2015).

Under the umbrella of the SDGs, the opportunity was found to create a group of university lecturers and professors to join others who were already working along these lines. The topics covered under the auspices of the SDGs coincide with those focused on DEGCE, thus the SDGs provide a programme of educational content to cover the key elements for understanding and addressing current global challenges. The United Nations is the sponsor of the SDGs, giving them a great deal of visibility that should be maximised. Moreover, they attract widespread international support and offer a framework for collective action on global poverty eradication. The 2030 Agenda is a facilitating framework that has allowed for the establishment of objectives such as: enabling undergraduates to be informed, educated and committed regarding poverty and its causes, and the economic, political and social interrelationships between the global North and South; promoting values and attitudes related to solidarity, social justice and human rights; and enabling them to effectively contribute to achieving the SDGs.

This article describes the strategies for the creation of an educational innovation project that enabled the training of university lecturers to introduce the content and values of DEGCE into their subjects. It focuses on the specific case of the macroeconomics subjects taught as part of the Marketing and Market Research Degree at the University of Málaga, and the global governance and comparative politics subjects taught in several degrees at the Complutense University of Madrid. We outline how the SDGs were used as a teaching resource and describe how lecturers and university students viewed this experience. Finally, we also offer some conclusions that analyse the successful aspects, as well as opportunities for improvement.

Our approach to the 2030 Agenda: a necessary critical vision

Incorporating the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs into university social science teaching is an exercise that is both complex and necessary. It is complex because it involves addressing elements of a different nature: it raises epistemological questions and requires theoretical reflection with a critical perspective. It also raises methodological questions about how to develop teaching practices that enable the incorporation of content linked to the 2030 Agenda. And it is necessary because it offers a way to address the challenges we face in the social sciences (Gil, 2022).

Before going into the more applied aspects of teaching practice, we want to make some observations on the epistemological and theoretical perspective adopted in relation to the 2030 Agenda. The approach adopted assumes that the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs are not in themselves a sufficient mechanism to drive structural transformations. Their mere existence will not place sustainable development at the centre of the policies and actions of global society actors. For this to happen and for this agenda to be truly meaningful, a critical and transformative outlook is needed. Only in this way can the 2030 Agenda become a political framework capable of guiding critical and transformative action in relation to the current hegemonic development approach (Martínez-Osés and Martínez, 2016).

If, on the other hand, we consider the 2030 Agenda to be a ‘technical recipe’, we would be accepting the neoliberal framework for the reproduction of problems (McCloskey, 2019). This framework is also compatible with the 2030 Agenda, but not without a critical and transformative vision of it. Understanding teaching as a critical exercise that addresses the challenges of the current multidimensional crisis requires a multidisciplinary approach to teaching. It also requires a critical perspective on the 2030 Agenda, one that highlights the redistributive and pro-global justice character implicit in many of the SDGs and their targets, and incorporates the necessary ecological perspective on the interpretation of the challenges and goals. Moreover, a perspective that recognises the importance of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities, which leads to the assumption that the current situation is the result of an unequal distribution of power, opportunities and resources.

All these elements, explicitly or implicitly present in the 2030 Agenda, call for a rethinking of the different disciplines and subjects taught by the university lecturers and professors involved in the teaching innovation project: economics and political science. The more orthodox approaches traditionally presented in academia are thus called upon to be more open and rethink their own objects of study. The 2030 Agenda and the SDGs, and especially a critical and transformative vision of these, constitute a unique opportunity for this paradigm shift.

Creation of a working group based on an Educational Innovation Project

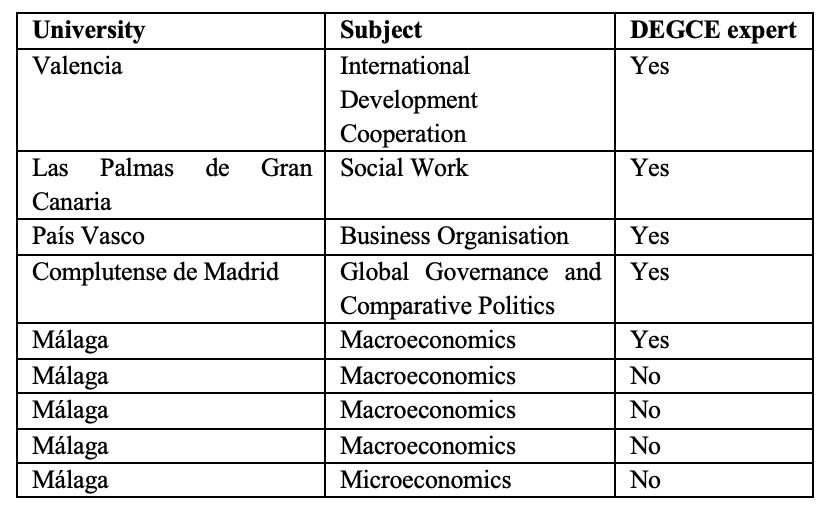

A programme at the University of Málaga in Andalusia, promotes Educational Innovation by bringing together professors and university lecturers. Its appeal to participants is based on the fact that it offers several incentives, both of an intellectual nature and in terms of professional development. It serves as a means to create interdisciplinary research teams, encourages research and scientific publications, provides a small amount of funding and, in addition, participants receive a certificate of participation that provides useful points for professional advancement. One of the projects approved in 2019 brought together nine university lecturers and professors from different disciplines and universities in Spain, (see Table 1).

Table 1: Interdisciplinary Group Components

All the members of the group who do not belong to the University of Málaga teach different subjects, but they all share the common characteristic of being experts or very familiar with DEGCE. In contrast, the lecturers at the University of Málaga were not familiar with this educational process, with the exception of the project coordinator who called on colleagues from the same department to be part of the intervention group, a proposal that was well received in all cases. The fact that they were close by and taught the same subject, facilitated the monitoring of the training process.

The end goal was that the working methodology and educational intervention adopted by the new trainee lecturers should emulate what the more experienced professors and lecturers in the group were already doing. That is to say, contextualising the different subjects involved to give undergraduates a sense of the socio-economic and environmental reality that surrounds them. It was also important to introduce issues related to sustainability in everyday life in order to address them later on in a permanent way and from different areas and disciplines. The SDGs were used as a vehicle to incorporate cross-cutting concepts and activities. This complemented the training of the university students involved, enabling them to become sensitised professionals, able to look at problems critically and to be equipped with the answers provided by the various disciplines. The undergraduates were exposed to aspects of reality that are not usually dealt with during teaching practice and which relate to the three dimensions of sustainable development: economic, social and environmental.

The diversity of subjects covered in the group, with different levels and timetables for each subject and faculty, meant that a certain degree of autonomy was required. Thus, from the outset, the implementation of the programme was flexible, making it easier to adapt to the specific needs of each lecturer, subject and group of undergraduates. It also meant that activities could be adjusted to the circumstances arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, it has shown that, regardless of the subject taught, discussions regarding solidarity can also be incorporated into university courses.

Training for practising university lecturers

One of the first steps taken to provide training for university lecturers with little or no experience of implementing DEGCE, was to propose an initial action-research task. This involved finding experiences and teaching methodologies currently used in Spanish universities to integrate, disseminate and help achieve the delivery of the SDGs in traditional subjects. A preliminary review of the scientific literature identified a significant number of conference papers by university lecturers describing their experiences. The variety of pedagogical methodologies found and applied for this purpose was remarkable, thus facilitating the work of compiling the various methods, procedures and common practices carried out. This resulted in a synthesis of results, recommendations and conclusions drawn from these experiences.

This activity provided a better understanding of what DEGCE is, how it is implemented, in what situations and by whom, as well as its connections with the SDGs. A brief inventory was drawn up describing the most appropriate interventions in each situation. This served as a database for consultation, as well as to find out which universities are incorporating these educational practices into their teaching activities. A mapping phase was set up to find out what was already being done, and a limited research project was formally carried out that compiled methodologies used to introduce the SDGs in universities. The inventory serves both as a model and as an incentive for other lecturers to implement the SDGs.

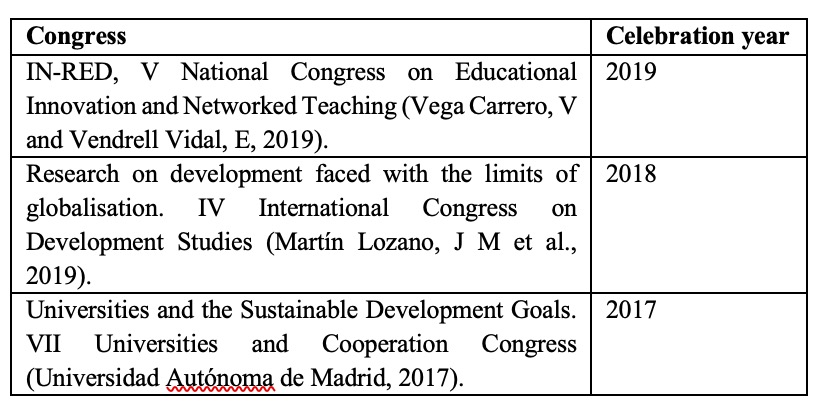

Using the classic review methodology, we analysed the most representative experiences of thirty-nine papers from the three conferences listed in Table 2. Their proceedings were chosen as databases because they were related to educational innovation and implementation of the SDGs in Spanish universities. In turn, at the end of 2019, the result of this research was presented at the VIII University and Development Cooperation Congress held in Santiago de Compostela.

Table 2: Congress Proceedings Consulted

This review highlighted the significant number of activities carried out in other universities, which served as a great motivation for our trainee university lecturers. It provided confidence, since the methodologies used for the DEGCE interventions were familiar to the lecturers, as in many cases the innovation consisted of making small changes to a known teaching method or the combined use of methodologies.

The search also found a wealth of recommendations for involving more actors outside the teaching environment. This helped to understand the positive impact of collaboration with other groups, provide confidence to disseminate what is being done, and to focus on working with others. Recommendations were found to create discussion groups with university teaching staff, involve institutional departments and services, as well as include non-university institutions, social organisations and other external actors that can influence the training of university students, such as organic and sustainable production companies, civil society organisations, public institutions and others.

The papers consulted also provided advice on DEGCE activities, concluding that the more practical, participatory and active they are, the more effectively they attract new participants, in addition to gaining greater recognition as transformative experiences. It was also concluded that the more time spent on DEGCE and the earlier in the university students’ life the work is started, the more is achieved. It is not advisable, therefore, to wait until the final years of the degree or until internships begin to intervene.

Adapting and introducing the SDGs in each subject area

The project explored the links between the content of each subject and the SDGs and their targets so that a critical analysis could be introduced at the appropriate time. This task became part of the undergraduates’ assessment, as this approach complemented, contrasted, or reinforced the knowledge traditionally acquired in the subjects in question.

In general, and not only for the case study presented in this article, but it is also relatively easy to refer to different SDGs in microeconomics, macroeconomics or political science subjects. The possibilities for including them are wide-ranging. Among others, we could give the example of microeconomics, where externalities are studied, i.e. those activities that once carried out can affect others, such as the production of emissions or pollution. Microeconomics analyses different solutions from an economic point of view, but it can also introduce concepts in which the goals and SDGs are not met. The emission of polluting waste can undermine the achievement of the first SDG, making those affected more vulnerable and reduce their average income. It can affect the third and sixth SDGs if the discharge harms health, wellbeing, and clean water, and it affects the tenth SDG because it can increase inequalities, among other distortions. In this way, connections and responses emerge that are simultaneously part of the economic sphere and the field of sustainability. Thus, terms such as the circular economy, green economy or degrowth make sense, as these alternative economies also provide solutions. This intersection makes it easier to understand the link between economic disciplines and the SDGs, which are aimed at fulfilling human rights, the same goal as that of DEGCE, which is also based on the protection of human rights.

In economics, it is argued that sustained growth in production achieves healthy economic rates, but this is challenged by the biophysical limits of our planet. When we come to this issue in the subject, it creates an opportunity for undergraduates to explore the possibility of achieving sustainable economic growth while using fewer resources. Thus, concepts such as improving productivity and technology, promoting a greater supply of services rather than goods, or repairing obsolete products so that they can be reused, make sense. It also makes sense to raise awareness among people of the need to set sustainable targets, since they are the ones who create the demand. This makes it easier to understand that companies can change consumer behaviour according to their values, and that consumers can demand changes from companies. In this brief process, we can talk about the ninth, eleventh, twelfth, fifteenth and other SDGs. The SDGs offer the opportunity to move freely between them, to go through them and address the different issues they contain because they all form a single whole. This is an advantage because the SDGs make it easier to implement DEGCE issues.

It does not take long to add a critical analysis that compares the content of these subjects with the SDGs, increasing the elements of judgement that help to better understand the subject, while raising awareness and educating university students on the issues that have concerned the DEGCE.

In macroeconomics, there is a central topic of study: the labour market, where people are considered as factors of production, capable of generating greater output and wealth. It relates directly to the eighth SDG: ‘Decent Work and Economic Growth’. Traditionally, models of labour market functioning are studied based on the assumption that wages can be varied flexibly, ignoring the social effects this could generate for workers. But no distinction is made about different human natures and needs. This is an opportunity to draw attention to the fifth and tenth SDGs, which aim to reduce inequalities, whether gender-based or otherwise. This topic also makes it easier to talk about immigration as a phenomenon that increases the host country’s wealth. An immigrant, regardless of whether he or she joins the labour market or not, consumes. To satisfy this consumption, more must be produced, and this creates new jobs. From an economic perspective, there is no room for hate speech, xenophobia or racism, as immigrants are a source of wealth and, through remittances, contribute to development in their country of origin and host country. But the question also arises: what causes migratory flows? We find that many of the answers lie in the fact that it is very difficult to achieve the goals set out in the 2030 Agenda in their country of origin.

Once the initial phases of the pandemic had passed and normality had resumed in the 2021-22 academic year, other activities for undergraduates could be organised. In particular, they were asked to work in teams for the macroeconomics course and to write an essay that began by explaining what the SDGs are, their origin and other general aspects, followed by a more in-depth exploration and analysis. In addition, the group was required to connect a specific goal or target of their choice with specific aspects of the subject, provided that they were different from those considered to date. This exercise can be asked of university students, as there is a wealth of information on the SDGs, readily available examples and facilities for self-learning. There was a day set aside for each group to present their ideas to their classmates. This day constituted a real immersion in the 2030 Agenda, providing new insights and nurturing new interconnections between the SDGs and the subject. The activity was awarded marks for the subject, and this was an incentive that ensured the students worked harder. As a result, new points of view were obtained which offered the opportunity for fresh debates and further learning. Marks were based on originality, reliability, significance of the findings and presentation.

Another exercise which was voluntary but still awarded marks asked university students to work individually to identify an observable event where companies or institutions took action towards the achievement of the SDGs. Thanks to this exercise, participants learned about the Global Compact - a UN initiative that is leading the way in corporate sustainability across the world - and through which they obtained a large pool of real examples of companies’ actions.

Outside the classroom environment, the university building was decorated with SDG logos, which continued to be displayed afterwards. Several videos were also played cyclically in the foyer of various faculties for weeks, showing the university students associating themselves with different SDGs. Part of the project budget was used for this, with the involvement and support of the Dean’s staff of the faculties involved, to whom we would like to express our gratitude. The aim of putting up eye-catching posters and videos outside the classrooms was to arouse the interest of other undergraduates who share spaces in these faculties and of the educational community in general.

Discussion

University students’ perception of the experience

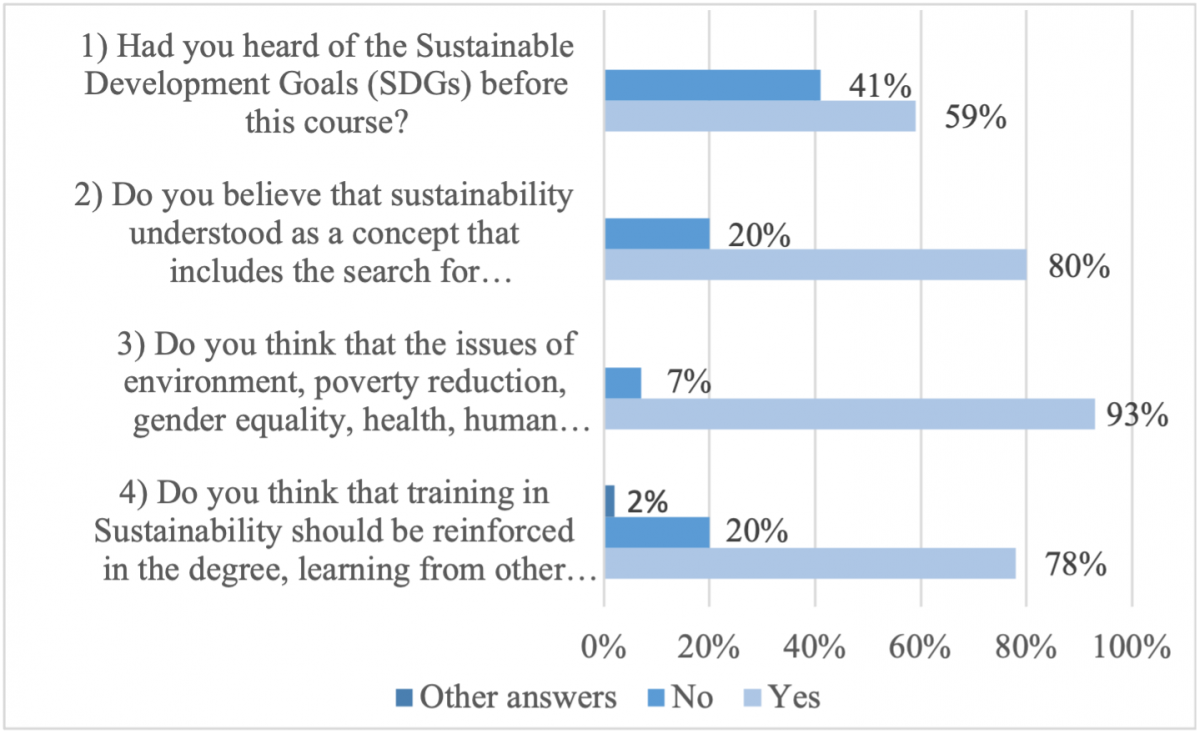

By means of an online survey carried out in June 2022 with 211 macroeconomics undergraduates in the University of Málaga, we assessed the students’ perception of the experience of incorporating the SDGs into the subject. The questions and their answers are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: University student perception survey on the inclusion of the SDGs in macroeconomics

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on respondents’ data.

When asked if they had heard of the SDGs before this academic year, more than half said ‘yes’. When asked the same question three years earlier, in the 2019 academic year, only thirty-six per cent of the undergraduates surveyed said they knew about them. It could be interpreted that word of mouth, knowing that academic activities are being carried out with the SDGs, the dissemination work with posters and videos displayed in the common areas of the faculties, has contributed to making the concept known or, at least, they are more familiar with the image and symbols displayed and what they represent. In the second question, the answer is largely affirmative, but twenty per cent are sceptical, choosing the answer given as an alternative: ‘No, I think it is far from becoming a reality, it is a utopia’.

When asked whether they believe that the issues addressed in the SDGs are important for their current education and future professional practice, the majority answered ‘yes’, but seven per cent chose the negative option offered in the survey, which was as follows: ‘No, I think they are issues that correspond to personal ideological and not professional reflections, such as religious beliefs or political affinities’. For this small percentage of respondents, our interpretation is that the topics included in the SDGs are considered to be alien to the training and professional sphere. In the fourth and final question, a large proportion of respondents believed that this type of training should be reinforced in the degree, but twenty per cent stated that it is not necessary and that seeing it in a single subject is sufficient. A third option was given as an answer, chosen by two per cent of the undergraduates, who considered that these topics should not be included in any subject of the degree.

University lecturers’ perception of the experience

Among the difficulties encountered, whether within the group itself or other complexities of external origin and which may require support, are the following: despite the diversity of the teaching staff and subjects involved, the cross-cutting implementation of content and values that comprise the DEGCE, was successful in contextualising the SDGs in each subject. Among the less experienced members of the group, it was found that this teaching activity may initially have seemed contrived and required high levels of knowledge and experience to be integrated in a smoother and more natural way, although once trained, they did not find it difficult to introduce DEGCE into the subject. With this activity, a trend has been set, and although the project was initially scheduled for the 2019-2020 and 2020-2021 academic years, it continues to be implemented today, even without the sponsorship that prompted it. Thus, we can affirm that university lecturers who have been trained, are sensitised, and introduce DEGCE into their teaching because of personal motivation and because better academic results were observed. As Laurie et al. (2016) point out, introducing DEGCE and its questions into a subject brings quality to education, strengthens students’ critical thinking and their ability to reflect, debate, approach and seek solutions from different perspectives, as well as providing better levels of knowledge of the subject, which they can use as a tool to address global problems.

In faculties where only one subject of the degree course introduces the SDGs, other activities and subjects dealing with these issues were needed in order to standardise these contents and prevent the entire load from being concentrated in one or two subjects. Another measure was adopted to strengthen administrative aspects and based on the aforementioned document that university authorities use to promote sustainability competences in the teaching guides of Spanish universities (CADEP-CRUE, 2012), so the teaching approach adopted, in which the SDGs are introduced, was made explicit in the teaching guides. Initially it sparked debate and raised concern among some lecturers as to whether including these terms could be interpreted as an ideological position or a personal conviction.

The SDGs include a complex range of social, economic and environmental challenges, and it is essential that future university-trained professionals are able to address these challenges and understand how their work can contribute to improving the socio-economic and environmental quality of their surroundings. For these reasons, the support of the university institution as a trainer of the educational community in general is necessary so that, in turn, it can contribute to the development of the academic and professional skills of university students.

Conclusions

The aim of the Educational Innovation Project presented in this article was to train practising university lecturers to introduce DEGCE through their subjects, incorporating the SDGs in a cross-cutting way in various subjects and Spanish universities in a coordinated manner. It contextualised and established a dialogue of all the contents of each of the subjects involved with the challenges of sustainability. At the same time, university student training was complemented, generating critical analysis, reflections, proposals and actions, in order to achieve professionals who are aware of and committed to aspects of reality that are not usually considered in the teaching practice, and which belong to the three dimensions of sustainable development; economic, social and environmental.

Moreover, it can be affirmed that the desired results have been achieved in the training of university lecturers who were able to actively implement DEGCE content using the SDGs as a tool. In several faculties that have taken part in the Educational Innovation Project, all undergraduates have benefited in at least one subject and for at least one academic year. According to a survey carried out in June 2022, shown in Figure 1, it is clear that, with some exceptions, the student body is satisfied with and values this additional training. However, it is a challenge for professors that a small proportion of them stop seeing the achievement of better levels of sustainability as a utopia, to understand that it can be useful for their professional training, or that these issues are seen as values that have a place in the university environment.

The Educational Innovation Project has carried out methodological and practical proposals that promote integral development in university students, in aspects such as social justice, diversity, autonomy and participation in solidarity actions and development cooperation projects. This, as well as supporting initiatives that respond to improvements in problematic situations, and that facilitate undergraduate self-knowledge. The lecturers who took part in this Educational Innovation Project have received training, that has been strongly supported by other more experienced lecturers and professors. In-service university lecturers have been trained using methods that are highly familiar to them, such as small research projects and meetings at specific congresses where there are other experts in DEGCE. Furthermore, multidisciplinary and inter-university coordination has been promoted, making it easier for inexperienced lecturers to gain access to support.

The SDGs are the supporting conceptual framework that, while it is accepted that they may have their criticisms, helps to implement DEGCE content, as it brings together the most important issues in terms of sustainability and triggers various analyses. In addition, the generally accepted view that the SDGs movement, its brand, and the prestige of the institution that promotes them, the United Nations, has helped to ensure that in the poster and video exhibitions displayed in faculties they are seen as natural and are generally accepted, which contributes to normalising the presence of solidarity concepts in the university environment.

A reward and recognition system have proven to be important, both for undergraduates and lecturers, as it is a powerful stimulus that attracts and increases interest in the task. University students received points for the teamwork related to the SDGs, and the lecturer received points counting towards their career advancement by participating in the Educational Innovation Project. This has ensured the training of the university students; also, initially attracted the lecturer to participate in the project. The lecturers, once they have been trained in DEGCE, then continue to implement this way of teaching, even if they no longer receive points, because of personal motivation and because they observed better academic results for their undergraduates.

For future iterations of the programme, both internal improvements and external support would be needed. This requires increasing knowledge among members of the teaching staff so they can put this into their teaching practice with greater skill and ease. To achieve this, the support of the university institution would be positive, favouring and increasing the channels for non-curricular education, training the educational community in general, so that in a global and homogeneous way it contributes to the development of academic and professional skills in sustainability issues. However, it would also be helpful if the university institution could provide more in-depth support to faculties implementing DEGCE through the SDGs by, for example, relaxing bureaucratic structures, standardising the cross-cutting inclusion of SDG content and values, adding sustainability competencies in teaching guides, and establishing more strategies that involve the teaching staff. In addition, other activities and subjects that deal with these issues could be included to prevent the entire load from being concentrated in one or two subjects of the degree course, as it may be ineffective to provide university students with the knowledge, skills and attitudes to understand and address the SDGs in a separate and isolated way.

References

CADEP-CRUE (2012) ‘Directrices para la introducción de la Sostenibilidad en el Currículum’, available: https://www.crue.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Directrices_Sosteniblidad_Crue2012.pdf (accessed 16 December 2022).

Gil, M L (2022) 'La Agenda 2030 y el imprescindible cambio de paradigma en la universidad', Dossieres EsF, (47), Autumn, pp. 4-6.

Kestin, T, van den Belt, M, Denby, L, Ross, K, Thwaites, J and Hawkes, M (2017) ‘Getting started with the SDGs in universities: A guide for universities, higher education institutions, and the academic sector’, Sustainable Development Solutions Network, Australia, New Zealand and Pacific Edition.

Laurie, R, Nonoyama-Tarumi, Y, Mckeown, R, and Hopkins, C (2016) ‘Contributions of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) to Quality Education: A Synthesis of Research’, Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, Vol. 10. No. 2, pp. 226–242.

Martín Lozano, J M, Ortega Carpio, M L, Sianes, A and Vázquez de Francisco, M J (ed.) (2019) ‘La investigación sobre desarrollo frente a los límites de la globalización. Actas del IV Congreso Internacional de Estudios del Desarrollo’, 12-14 December 2018. Córdoba. Fundación ETEA, Instituto de Desarrollo de la Universidad Loyola Andalucía. available: https://onx.la/42f70 (accessed 16 December 2022).

Martínez-Osés, P J and Martínez, I (2016) ‘La Agenda 2030: ¿cambiar el mundo sin cambiar la distribución del poder?’, Lan Harremanak - Revista De Relaciones Laborales, No.33, pp. 73-102.

McCloskey, S (2019) ‘The Sustainable Development Goals, Neoliberalism and NGOs: It’s Time to Pursue a Transformative Path to Social Justice’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 29, Autumn, pp. 152 -159.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2017) ‘Education for Sustainable Development Goals - Learning Objectives’, Paris: UNESCO, available: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000252423 (accessed 16 December 2022).

United Nations General Assembly (2015) ‘Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’, resolution adopted by the General Assembly, A/RES/70/1.

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (ed.) (2017) VII Congreso Universidad y Cooperación al Desarrollo. La Universidad y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. 29-31 March 2017. www.uam.es: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, available: http://www.robolabo.etsit.upm.es/aguti/publications/Mataix-etall17_ITD.pdf (accessed 16 December 2022).

Valderrama-Hernández, R, Alcántara Rubio, L, Sánchez-Carracedo, F, Caballero, D, Serrate, S, Gil-Doménech, D, Vidal-Raméntol, S and Miñano, R (2020) ‘¿Forma en sostenibilidad el sistema universitario español? Visión del alumnado de cuatro universidades’, Educación XX1, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 221-245.

Vega Carrero, V and Vendrell Vidal, E (ed.) (2019) IN-RED 2019: V Congreso de Innovación Educativa y Docencia en Red, www.lalibreria.upv.es: Editorial Universitat Politècnica de Valencia.

Maria Inmaculada Pastor-García has a degree in Economics and Business Sciences from the University of Málaga (1998). She holds a Master’s degree in International Cooperation and Development Policies from the same University. Her Doctorate thesis dealt with the evaluation of development education in formal education. She has worked since 1999 in private companies, acquiring knowledge and experience in the fields of accounting and financial management in the commercial distribution and construction sectors. She has combined this work with the teaching of different groups and at different levels. Since 2008, she has been an Associate Lecturer in the Department of Economic Theory and History in the University of Málaga. She has undertaken several professional development courses to enhance her pedagogical knowledge. She maintains a strong interest in the social and solidarity economy and international cooperation.

Ignacio Martínez-Martínez holds a PhD in Development Studies from the University of the Basque Country and a Master’s degree in International Politics: Sectoral and Area Studies from the Complutense University of Madrid. He is Professor of Political Science in the Department of Political Science and Administration at the Complutense University of Madrid. In the Faculty of Political Science and Sociology he teaches Comparative Politics, Public Policy and Global Governance. Previously, he was an Associate Researcher at the Complutense Institute of International Studies and the Department of Applied Economics in the University of the Basque Country. His doctoral thesis was awarded in 2020 with the Manuel Castillo Prize, one of the most prominent prizes in Spain specialising in research on human rights and human development.

Antonio Francisco Rodríguez-Barquero holds a degree in Economics and Business Administration from the University of Málaga (1997). He has a Master’s Degree in International Cooperation and Development Policies from the same University. He has worked for twenty years in private companies in cost control and financial management departments, as well as financial analysis. Since 2017, he has been teaching at Málaga University in the departments of Public Finance, Economic Policy and Political Economy, as well as in the Department of Economic Theory and History and Economic Institutions as a Substitute Professor. His current fields of interest are circular and solidarity economy and international cooperation.