Promoting Democratic Values in Initial Teacher Education: Findings from a Self-Study Action Research Project

Development Education and Democracy

Abstract: Democracy and global education are intrinsically linked in their shared commitment to debate and the opportunity to evaluate multiple perspectives and make informed decisions on topics that impact the world around us. A focus on critical thinking within education offers the opportunity to teach students the skills necessary to question the status quo, develop informed opinions and contribute to the preservation and promotion of democracy in society. This article explores a self-study action research project which took place across three academic years which aimed to identify effective approaches for incorporating critical thinking into initial teacher education. Research was undertaken with students in their second year of study and data sources included ongoing personal reflections, critical conversations with two colleagues who acted as critical friends, alongside a variety of data collection approaches undertaken with students. This research project was undertaken in response to an identified gap between students perceived levels of criticality and the skills they would demonstrate during class time or within assessments. Consequently, this research project focused on identifying strategies to successfully support students to both demonstrate criticality and to understand and identify core critical thinking approaches relevant to global education. Findings indicated that students had the capacity to become critical thinkers and develop an understanding of the potential impact for their future teaching. A focus on providing opportunities to practice critical thinking in a supported setting was key for students’ skill development. The consistent incorporation of active, engaged opportunities to share ideas and work collaboratively supported students to develop core critical thinking skills.

Key words: Critical Thinking; Democracy and Global Education; Initial Teacher Education; Self-Study; Dialogical Approach.

Introduction

This article aims to highlight the impact that a focus on critical thinking can have on promoting democracy within the context of global education. Through examination of the relevant literature this article begins by presenting the argument that fostering criticality within global education is crucial to nurturing democratic citizens. The article continues on to present the methodology and findings from a self-study action research project which took place within initial teacher education (ITE) in Ireland. The study was undertaken with student teachers in the second year of their degrees, and explored approaches to support their development of critical thinking skills. Findings from this study demonstrate the potential for a focus on nurturing critical thinking skills within ITE to promote democratic values amongst students. The study found that participative dialogical teaching approaches worked effectively to provide students with opportunities to practice their critical thinking in a supportive and structured setting.

Global education and democracy

In the recent Dublin Declaration, the Global Education Network Europe (GENE) (2022: 2) defined global education as:

“education that enables people to reflect critically on the world and their place in it; to open their eyes, hearts and minds to the reality of the world at local and global level. It empowers people to understand, imagine, hope and act to bring about a world of social and climate justice, peace, solidarity, equity and equality, planetary sustainability, and international understanding. It involves respect for human rights and diversity, inclusion, and a decent life for all, now and into the future”.

One of the key challenges global education has faced as an educational approach grounded in its commitment to social justice, human rights and equity, is the rising support internationally for political parties and perspectives with narrow nationalist agendas (GENE, 2020: 6) and the increase in xenophobic populism and hate speech in societies (Council of Europe, 2018). Westheimer (2019) cites the election of Donald Trump and the Brexit votes in 2016 as two examples with significant global consequences in which the winning parties employed right-wing nationalism to rally supporters against the common enemy of ‘foreigners’, promoting racism and bigotry in politics. McCartney (2019) cautions that populism, such as these examples, enables the erosion of democracy and democratic values.

Democracy is commonly thought of as ‘power of the people’ due to the Greek origin of the word. While there are varied approaches to democratic governing around the world, the Council of Europe (no date) states that:

“properly understood, democracy should not even be ‘rule of the majority’, if that means that minorities' interests are ignored completely. A democracy, at least in theory, is government on behalf of all the people, according to their ‘will’”.

Consequently, democracy, by definition, should value multiple perspectives and afford genuine opportunities for opposing sides to be heard, to share knowledge based in lived-experiences and factual balanced research, ultimately enabling citizens to make informed choices and navigate compromises.

McCartney (2019) maintains that democracy is being lost through the rising support for narrow nationalist politics and that education must answer the call of John Dewey (1910) in ensuring that democracy is born new and fostered in every generation to counteract and challenge passivity in society. Where democratic values are under threat in society, so too can global education be pushed to the margins in favour of more passive approaches to education focused on compliance rather than debate and dialogue. Westheimer (2019: 9) declares that the waning trust in democratic values and the ‘toxic mix of ideological polarisation’ currently seen in countries across the world makes it critical that education should ask learners to imagine more just societies, should provide learners with multiple perspectives on controversial issues, and should actively teach them to be critical. He believes that centring education on democratic values and promoting critical thinking is crucial to counteract rising xenophobic populism (Ibid.).

Through education which is focused on the ideals of democracy and committed to social justice, students learn to question and become critical thinkers. Like Dewey, hooks (2010: 14) proposes that democracy must be reborn in every generation so that freedoms can be maintained, or where necessary, fought for. This article proposes that where criticality, curiosity, and creativity are not fostered in education, it is not possible to nurture active democratic citizens committed to challenging injustice and acting to change society. In this way, the promotion of democratic values in society and the teaching of critical thinking in schools are inextricably linked.

What is critical thinking?

Dewey (1910: 6), seen by many as the father of critical thinking in education, defines reflective thinking, widely accepted to be synonymous with critical thinking, as ‘active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it, and the further conclusions to which it tends’. Critical thinking theorists have often mirrored Dewey’s contention that critical thinkers must employ persistent effort and knowledge, skills, and attitudes that ensure they are disposed to examining beliefs and ideas.

However, critical thinking is not inherently concerned with social change. Indeed, Linskens (2010) asserts that while critical thinking focuses on identifying and examining falsehoods in ideas, it is not innately concerned with rectifying the consequences of these falsehoods. It is in its connection to critical pedagogy that critical thinking offers an opportunity to contribute to the transformation of society and a focus on democratic values. Freire (1970) positioned critical thinking as a fundamental component of critical pedagogy, asserting that we must not simply critically reflect upon existence but critically act upon it. Commenting on Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Ibid.), Giroux (2010: 16) proposes that for Freire, critical thinking was ‘a tool for self-determination and civic engagement’ in presenting a way of breaking the cycles of history by ‘entering into a critical dialogue with history and imagining a future that would not merely reproduce the present’. Critical pedagogy is, by definition, attentive to social change and justice through theoretical, political, social, and cultural framings (Giroux, 2011). Critical thinking was the core skill advocated by Freire (1970) to enable learners to challenge orthodoxies and imagine and work towards alternative futures.

Critical thinking and global education

Critical thinking and global education share a commitment to unravelling and analysing varied perspectives and experiences and in doing so encourage learners to challenge orthodoxies and imagine alternative futures. A focus on critical thinking within global education provides a counter approach to the educational direction seen in many countries around the world tending towards high stakes testing which usually rewards recall over criticality. This passive approach to education runs counter to the aims of democracy and the dialogical approach which is fundamental to democratic education.

Furthermore, the promotion and development of critical thinking within the context of global education is central to supporting learners to navigate the challenging nature of global education topics. It is commonly cited (Andreotti, 2006; Shah and Brown, 2010) that many of the issues that global education is concerned with are contested and necessitate engagement in discussion and exploration of multiple perspectives to support a broader awareness of issues and challenge dominant discourses. MacCallum (2014: 39) contends that global learning is a process of ‘realized critical thinking’ which allows for consideration of social, cultural, economic, political and environmental issues from multiple perspectives. Global education learners should come to understand that knowledge is not a fixed state but needs constant critical evaluation as they engage with new perspectives and experiences.

The research study which this article explores identified a set of core critical thinking skills relevant to the context of global education. These skills were identified through an extensive literature review and finalised in conjunction with empirical research findings. The identified skills include developing and using a global learning knowledge base, learning to question orthodoxies, engaging in self-reflection, and using a values-based lens when exploring global justice issues.

The centrality of Initial Teacher Education

While education has the potential to uphold and reignite democratic values within society, this will not happen without a focus on teacher preparation. To pass on critical thinking skills within their future classrooms, teachers must first learn to become critical thinkers themselves (Maphalala and Mpofu, 2017; Pithers and Soden, 2000; Taşkaya and Çavuşoğlu, 2017; Williams, 2005; Sezer, 2008). ITE is a crucial space for ensuring that teachers are prepared for and committed to doing this work in their future classrooms. Indeed, Williams (2005) highlights that it is unlikely that classroom teachers will become skilled critical thinkers if critical thinking is not emphasised and fostered in ITE.

While critical thinking is often positioned as a core outcome of higher education (Lederer, 2007; Stupple et al., 2017), students often arrive with limited experience of critical thinking from their primary and secondary school educational experiences (Ghanizadeh, 2017). This can be correlated with the strong, and in some countries increasing, focus on standardised, high-stakes testing internationally and the consequent rote learning which permeates much formal education. Furthermore, limited exposure to criticality prior to entering higher education can mean that stereotypes and orthodoxies have become strongly engrained. ITE is an important space to challenge these pervasive, and often incorrect or dangerous, viewpoints prior to teachers entering classrooms through a focus on open discussion of competing viewpoints guided by a values-based lens (Williams, 2005).

Methodology

This article explores the outcomes of a self-study action research project which took place across three academic years within ITE in Ireland. As a teacher educator focused on the field of global education, I was motivated to inquire into my own practice and identify strategies to best support learners to develop their critical thinking skills. Prior to beginning the research project, I had found that students often self-identified as critical thinkers but I rarely saw the evidence of this in their class work or assessments. I undertook this research to explore this gap between their perceived and demonstrated skill levels and to ascertain what elements of my own teaching could either support or hinder them in developing and demonstrating the critical thinking skills I was looking for.

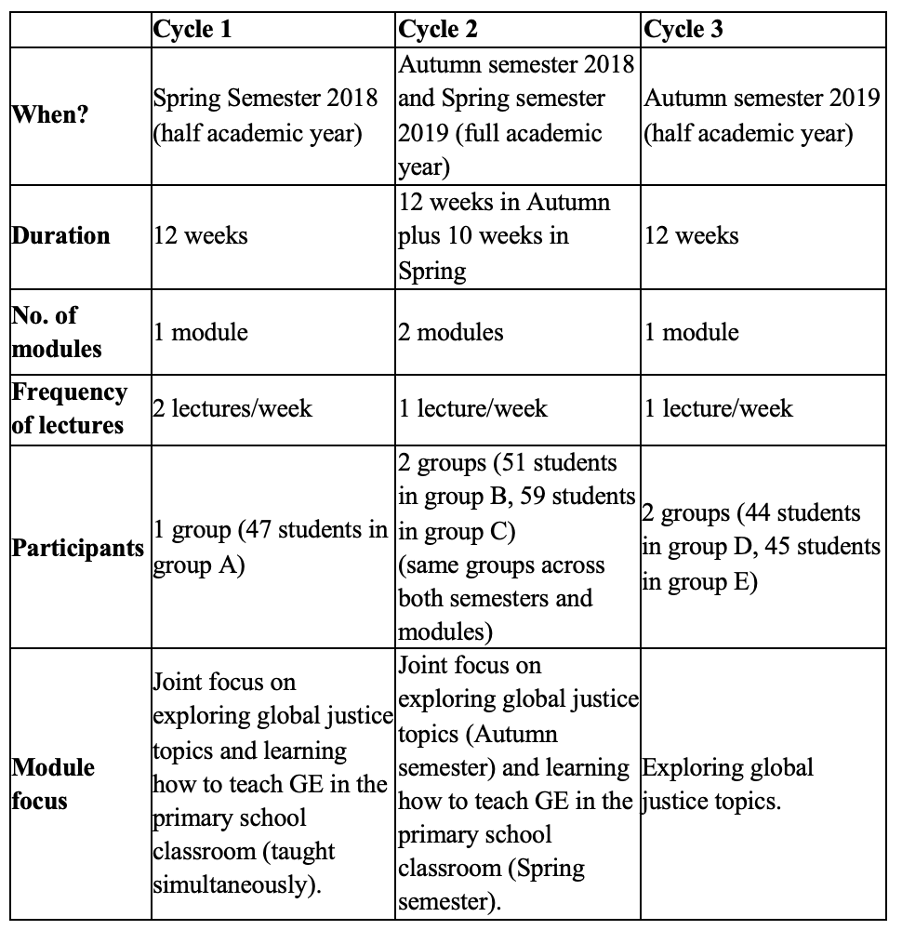

I undertook a three-cycle self-study action research process across three academic years. The main participants in this study were B.Ed. students in the second year of their degrees. I collected data during one of their core modules, social studies, which included global education as one-third of the module. Due to large cohort sizes on the B.Ed., students were taught in groups of roughly sixty on this module, with the same session being repeated seven times with different groups. During cycle one, just one of the seven groups took part in the study, during cycles two and three there were two groups who participated. Students were invited to participate and data was collected only from those who had given both written and verbal consent to participate. Table 1 details the structure of each cycle along with participant numbers and relevant module related details.

Table 1: Details of Action Research Cycles

The focus of the study was on examining my own teaching practices and the impact they had on students’ learning outcomes. During the first cycle I taught as I had done prior to the research project and reflected on what was and was not working. Using emerging findings from cycle one alongside the critical thinking skills identified through literature, I designed teaching interventions and made changes for cycle two, and then tweaked these again for cycle three in response to findings from cycle two. Changes included altering elements of my questioning style, including additional displays and adopting a new seating arrangement within the physical learning environment, introduction of new interactive teaching approaches alongside larger changes to my overall approach to teaching. Larger scale changes focused on the student experience and addressing the balance between content delivery and active, engaged learning opportunities. Just as the literature review shaped and informed my teaching and the interventions designed, so too did the emerging findings shape the structure of the skillset identified.

I adopted a self-study action research methodological approach which is commonly utilised by practitioners interested in studying and improving their practice and sharing the outcomes. Self-study research places the researcher at the centre of the inquiry they are exploring rather than investigating a topic in the abstract (Samaras, 2011). Although the motivation for the study related to my students’ learning outcomes, the research focus remained on my practice as an educator and its impact on their learning. As outlined by Roche (2016: 29):

“my pupils could be the mirror in which I saw my practise reflected, but I needed to see that I was researching ‘me’: my thoughts, my ideas, my solutions to problems, my actions, decisions and plans”.

While the research design suited the enquiry, there are recognised limitations to the self-study approach, particularly the generalisability of results. The nature of self-study research means that it is small-scale and findings are therefore context bound and cannot be generalised or applied beyond the context from which they emerged. I was conscious of this challenge throughout and worked to mitigate against it by offering my findings as an example for other educators to consider in light of their own contexts. Critically, the findings from this research respond to the need identified by Bourn (2020: 5) for ’research and evidence to demonstrate its [global education and learning] effectiveness, importance, and impact’ as this study demonstrates that it was possible for students to develop their critical thinking skills within the context of global education.

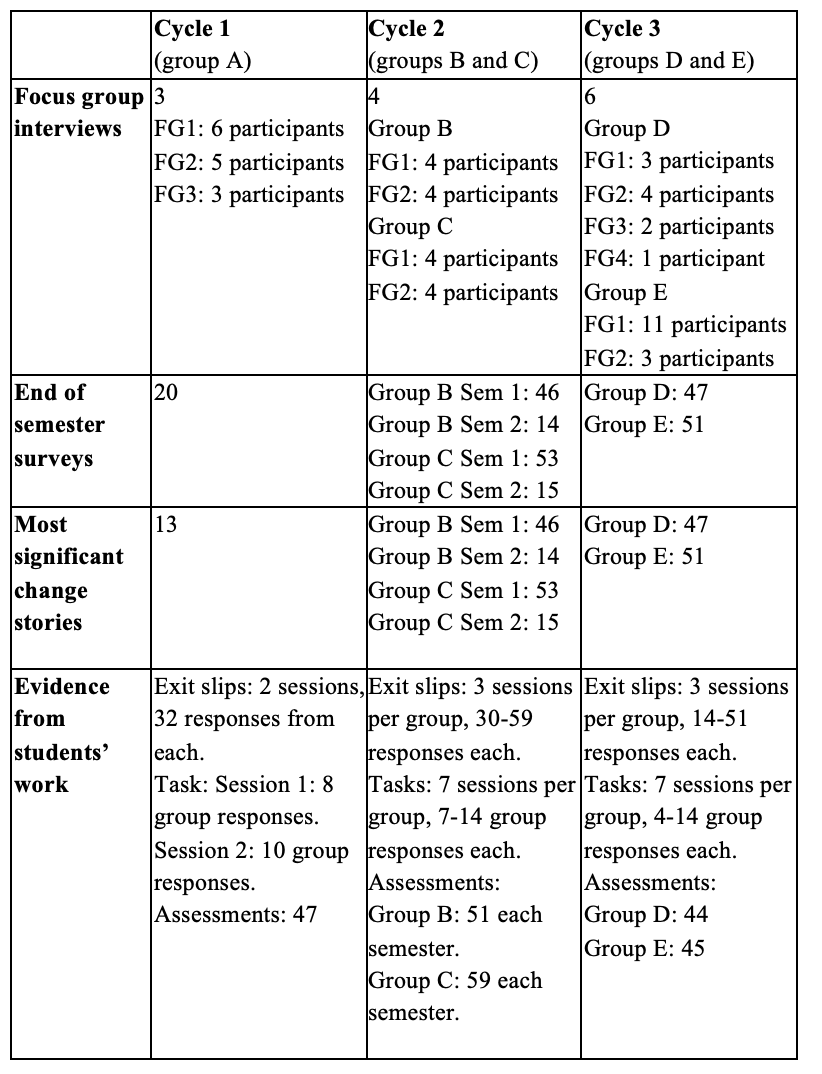

Although by its very nature self-study entails examining the self, it is not a purely introspective practice, but necessitates collaboration and drawing on sources of knowledge beyond the self (Samaras, 2011). Self-study legitimises the knowledge that educators can generate based on their own practices, however, this knowledge is the result of consultation and critical conversations with other relevant parties (Russell, 2008). The inquiry process I undertook in this project included support and engagement from my students, critical friends, and colleagues. Consequently, a variety of data collection approaches were employed across all three cycles. This included multiple means of data collection with students (see Table 1 below) alongside ongoing personal reflections and critical conversations with two colleagues who acted as critical friends.

I engaged in reflection in a number of ways throughout the three cycles of data collection. At the outset, I developed a set of simple questions to guide my reflections and narrow the focus of what I recorded to ensure it was relevant to the overall project. However, as time went on, I became more comfortable with the process and was better able to identify the moments or ideas of value without the aid of the guiding questions. I captured both written and audio reflections throughout the research process. When engaging with critical friends, data was gathered through recorded critical conversations, written feedback after observation sessions, and written reflections offered by the critical friends after our conversations or in response to particular problems or scenarios.

Table 2: Data Sources

The numbers of students involved in individual data collection methods varied based on students’ individual circumstances. While some data collection methods, such as surveys, Most Significant Change Stories (MSCSs), and evidence from class work were collected during class time, not all students within each group chose to contribute their class work as data, or chose to complete the surveys. Additionally, as focus group interviews took place outside of class time, participation from students was dependent on their interest in the research project and availability at the interview times. There was an effort made in all cycles to provide opportunities for participation at times which were suitable for students interested in taking part. Although there was variety in terms of participant numbers in different methods, all students in each group took part in at least one method. The variety of data collection methods helped to capture not only what was happening in the classroom but also included layers of interpretation through the multiple lenses of students sharing their own experiences and perspectives, my own reflections, and the considerations of critical friends who both observed me teaching and engaged in teaching the same materials themselves.

Following each cycle, interviews were transcribed and analysed and the emergent findings were used to inform and shape ongoing data collection. Quantitative data from surveys and MSCSs was minimal and was organised using excel which was then used to compare data and generate graphs which represented quantitative findings from each cycle. The purpose of the quantitative data was to offer side-by-side comparison (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2007) with the qualitative data findings and reveal where one set of data supported or contradicted the other. The qualitative data analysis employed within this study followed the steps for reflexive thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke (2020). There was a significant quantity of qualitative data to be analysed across all data sources and so the programme Nvivo was used to organise data and facilitate the process of analysis. Reflexive thematic analysis involved systematic data coding, both deductive and inductive. Themes were then developed and refined from the codes. All data sources were revisited at the conclusion of the three cycles and codes and themes were revised where relevant in light of new information from other cycles. Thematic maps were then created and used to structure the findings.

Both ethical approval and institutional approval were sought and granted at the outset of this research project. This ensured that the methodology was in line with best practice ethically, and that the institution where the research took place had approved the approach taken. Participants in the study were identified through purposive sampling. I had access to students through my post as a teacher educator and selected groups for inclusion in the project based on group composition in terms of student diversity to ensure a variety of student experiences and perspectives would be included. Written consent was gathered at the outset of each module and verbal consent was negotiated on an ongoing basis with students. Critical friends were identified and invited as a result of their professional relationship with me and connection to the relevant modules. Other ethical considerations which shaped the project included the potential impact of practitioner bias and the dependent relationship between my students and me as their lecturer. These considerations are typical in practitioner self-study research. The potential impact of bias was mitigated through open and ongoing discussions with participants and colleagues within academia. I addressed the dependent relationship by consistently reassuring students both verbally and through my actions that involvement in the study would not impact on the student-lecturer relationship. Additionally, I adopted a flexible and responsive approach to data collection which aimed at all times to be mindful of student wellbeing.

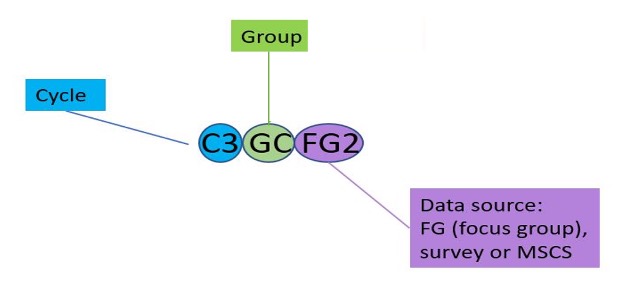

When sharing excerpts from the data, the source for each quote has been labelled following the structure outlined in Figure 1 below. This key has been used for focus group interviews (FG), surveys and MSCSs.

Figure 1: Key for identifying data sources

Findings

Although the findings from self-study research are not generalisable, they do present observations which have significance for others working within similar contexts (Sullivan et al., 2016). The findings presented here are the result of three cycles of data collection within modules that were shaped and modified in response to analysis and emerging findings from previous cycles. Throughout cycle one, I taught the module as I had done previously and focused the analysis of data on what was working well and where there were areas for improvement in relation to supporting students to develop their critical thinking skills. Based on analysis of data from cycle one the following changes were made within cycle two:

- Division of content across two modules allowing for focus on personal development prior to focus on teaching approaches;

- New assignment created that allowed for focus on understanding concepts, making connections between different concepts, and self-reflection;

- Re-envisaged specific sessions to include more interactive methodologies;

- Provide ongoing opportunities for feedback and questions;

- Introduced a baseline measure to gauge understanding of development and prior critical thinking experiences;

- Ensured that each topic had a variety of support materials in different formats online;

- Focus on asking questions of students – many of the first semester sessions were previously delivered to large groups so when used with smaller groups in cycle two, an effort to include more questioning was made.

While changes were made to teaching between the two cycles, findings from both cycles remained similar. Despite the changes, findings from both cycles show that while some students demonstrate an increased commitment to and engagement with criticality, many did not. Many students expressed a perception that they were being critical, but in practice I was still seeing many examples of uncritical work such as lack of reflection or an absence of questioning stereotypical interpretations of justice issues.

Following analysis of data from cycle two, and acknowledging the limited progression between the first two cycles I developed a two-part conceptual framework which was implemented in cycle three. The first part of the framework took the form of a model for teaching critical global learning, which was grounded in literature and informed by findings from cycles one and two. The model included a framework of core skills to be developed in the classroom alongside pedagogical considerations within the context of ITE. The second part of the conceptual framework was a planning tool which aimed to mitigate against challenges faced in the first two cycles. The planning tool included four lesson elements to be included in all sessions to ensure a consistent focus on the development of critical thinking skills. The elements included: a focus on presenting challenging content through indirect and direct teaching; opportunities to honour all voices through group work; ensuring that issues were personalised through individual work; and a sustained focus on collective responsibility through whole-class work. The combination of these lesson elements, which would range in time from just a few minutes to a more sustained focus depending on the session, led to the development of what one student described as a ‘discussion culture’ in the classroom.

The following findings focus on data from cycle three as this cycle was the culmination of the project and reflects all changes implemented as a result of analysis of data from cycles one and two. Consequently, the findings from cycle three offer the most significant learning from the research project in terms of factors which contributed to students’ acquisition of critical thinking skills. The findings showed that it was possible for these students to develop critical thinking skills within the context of global education and that a focus on dialogical approaches had a significant impact on their acquisition and demonstration of those skills. By the conclusion of the project, I saw a marked improvement in the gap between students perceived and demonstrated skill levels. Not only were students demonstrating critical thinking skills, but they were more aware of what critical thinking looks like in the context of global education. Although there was also an acknowledgement from students that the process of developing critical thinking skills was challenging due to their prior experiences. Describing the transition from post-primary to higher education, one student stated that ‘I know when I first went to university, when I left secondary school, I hadn't a clue about how to be able to think critically’ (C3GDFG1). This feeling was mirrored by other students who described having to adapt to ‘a totally different mindset’ and the struggle to adjust to a new way of thinking and learning. Students recalled the process of learning about critical thinking on entering higher education. One student described the experience as follows:

“everyone was talking about critical thinking and it’s so important but we never knew what it was or like … we never came across it before, but it’s kind of like we're developing it now, we're developing the skill” (C3GDFG2).

This was mirrored in other conversations at the end of each cycle where students shared that they were starting to find it easier to think critically now that they had the opportunity to practice the skills in class. The absence of critical thinking within student’s post-primary education was exacerbated by conservative family backgrounds for some, and by exposure to narratives within the media which do not encourage criticality or exposure to diverging perspectives. It was helpful to me to reflect on the transition that students were going through in their learning styles and to be mindful of this when considering my expectations for them.

Findings highlighted that one of the most transformational approaches utilised during the modules was affording students regular opportunities to practice critical thinking in a scaffolded way. As a result of the structure of the planning tool, students were provided with multiple opportunities during all sessions to share their ideas, experiences, to hear from classmates, and to work together to interpret and analyse information and external perspectives shared with them. Students felt that the opportunity to contribute during classes in multiple and diverse ways was very important to their learning and skill development, as captured by one student:

“I think we get to do so much interactive and group work and it's not all just sit there and put up your hand with an answer or … I feel like a lot of people are given opportunities if they didn't want to talk in front of the whole class, they still have an opportunity to get their opinion across. The different methodologies have already made it open to a lot of different learners and styles” (C3GDFG3).

Students also shared that the sustained focus on opportunities to practice sharing their perspectives across multiple classes in different ways helped them to develop and build their confidence and skill levels over time. One student highlighted this by stating that 'If you keep doing it like, you get more comfortable with it' (C3GEFG1). Group work opportunities were strongly highlighted by students across all three cycles as critical to building confidence in stating personal opinions or perspectives. Students indicated that when they had the opportunity to discuss topics in small groups of familiar peers first, this supported them to have the confidence to then offer opinions in front of the whole class.

When students engaged in group work, whole class work or individual work it always took place following a focus on knowledge development which was approached in a variety of ways from direct teaching using a PowerPoint presentation to student-guided learning using prompts, videos or readings. At the conclusion of each module students were asked to identify what the most significant change they experienced in relation to their criticality was, many students cited their increased knowledge-base, naming ‘being informed/educated in the module’, ‘the content from lectures’, and ‘my awareness on the topic’ (C3GDMSCSs) as catalysts for changes to their levels of criticality.

The final focus within the identified critical thinking skills and the lesson elements which were set up to facilitate learning those skills is self-reflection and personalising issues. Data analysis revealed that students appreciated opportunities to reflect during each session. Indeed, seventy-six per cent of students in cycle three reported that the most significant change they had experienced as a result of the module was that they were now more aware of their own opinions and values. Furthermore, not only were students indicating that the module supported them to become more aware of their own opinions, but that they appreciated that being given opportunities to engage in reflection also taught them that their perspectives were authentically valued in the classroom as they were given time and space. The following excerpt from a focus group interview highlights the importance of ensuring students feel that their perspectives are valued in the classroom:

Student 3: ‘To know that it's a safe environment where you can have your own opinion and not that you're going to be judged’.

Bighid: ‘And how do you know it’s a safe environment?’.

Student 3: ‘Because the lecturers are willing to hear what you say’ (C3GDFG2).

Opportunities to contribute and engage in activities through the lesson elements were accompanied by a focus on classroom atmosphere and a commitment to the ground rules within the approach ‘Open Space for Dialogue and Enquiry’ (Andreotti et al., 2006). This enabled me to ensure that I valued all contributions given, but that students knew I was also committed to questioning them. I regularly challenged students’ contributions and encouraged them to think about issues in different ways. In adopting this approach, I endeavoured to model the approach to critical thinking that I wanted students to engage in themselves. This approach appeared to deepen their self-reflection, and from my observations, did not hamper engagement as students continued to contribute diverse views.

Not only was there evidence of students demonstrating critical thinking, but students also showed an understanding of the significance of this new skill for them. Students were consistently conscious of their future roles in the classroom and the impact that their teaching could have. When discussing how they would integrate critical thinking into their own teaching practices during a focus group, one student stated that ‘you’re not forcing your own opinion then on other people and especially on children like, because they need to form their own opinion and thinking as well’ (C3GDFG2). Students showed an appreciation for different perspectives and a commitment to honouring multiple voices in their own classrooms.

Conclusions

Amongst the many lessons learned from this project was the importance of explicitly teaching critical thinking. This includes setting clear expectations for students in terms of what critical thinking looks like alongside providing opportunities for them to practice their criticality in a scaffolded manner in the classroom. The research project identified teaching strategies to counteract the passivity and tendency towards compliance evident amongst many students during this study and perpetuated by the media. The findings from this research highlight the potential transformative impact of dialogical approaches in the classroom in raising students' critical consciousness.

This article explored the impact that a focus on critical thinking can have in promoting democratic values in education. Critical thinking offers opportunities to counteract passivity and promote engagement in debate, encouraging citizens to make informed decisions, thus honouring the democratic focus on dialogue.

References

Andreotti, V (2006) ‘Soft versus critical global citizenship education’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 3, Autumn, pp. 40-51.

Andreotti, V, Barker, L and Newell-Jones, K (2006) Open Space for Dialogue and Enquiry Methodology: Critical Literacy in Global Citizenship Education. Professional Development Resource Pack, Derby: Centre for the Study of Social and Global Justice.

Bourn, D (2020) ‘Introduction’ in D Bourn (ed.) The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education and Learning, London: Bloomsbury Academic, pp.1-9.

Braun, V and Clarke, V (2020) ‘One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis?’, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), pp. 1-25.

Council of Europe (no date) Democracy, Strasbourg: Council of Europe, available: https://www.coe.int/en/web/compass/democracy#:~:text=The%20word%20democracy%20comes%20from,the%20will%20of%20the%20people (accessed 24 February 2023).

Council of Europe (2018) Unrelenting rise in xenophobic populism, resentment, hate speech in Europe in 2017, Strasbourg: Council of Europe, available: https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/-/unrelenting-rise-in-xenophobic-populism-resentment-hate-speech-in-europe-in-2017 (accessed 20 October 2020).

Creswell, J W and Plano Clarke, V L (2007) Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, California: Sage Publications.

Dewey, J (1910) How We think, Boston, D. C.: Heath and Co. Publishers.

Freire, P (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York, Continuum.

Ghanizadeh, A (2017) ‘The interplay between reflective thinking, critical thinking, self-monitoring, and academic achievement in higher education’, Higher Education, 74, pp. 101-114.

Giroux, H A (2010) ‘Rethinking education as the practice of freedom: Paulo Freire and the promise of critical pedagogy’, Policy Futures in Education, 8, pp. 715-721.

Giroux, H A (2011) On Critical Pedagogy, New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Global Education Network Europe (GENE) (2020) The State of Global Education in Europe 2019, Dublin: GENE, available: https://www.gene.eu/publications (accessed 11 August 2021).

Global Education Network Europe (GENE) (2022) The European Declaration on Global Education to 2050. The Dublin Declaration. A Strategy Framework for Improving and Increasing Global Education in Europe to 2050, Dublin: GENE

hooks, b (2010) Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom, New York, Routledge.

Lederer, J M (2007) ‘Dispositions toward critical thinking among occupational therapy students’, American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61, 519-526.

Linskens, C A (2010) ‘What Critiques Have Been Made of the Socratic Method in Legal Education: The Socratic Method in Legal Education: Uses, Abuses and Beyond’, The European Journal of Law Reform, 12, p. 340.

MacCallum, C S (2014) ‘Sustainable Livelihoods to Adaptive Capabilities: A global learning journey in a small state, Zanzibar’, Doctoral Dissertation, University College London.

Maphalala, M C and Mpofu, N (2017) ‘Fostering critical thinking in initial teacher education curriculums: a comprehensive literature review’, Gender & Behaviour, 15(2), pp. 9226-9236.

McCartney, A R M (2019) ‘The rise of populism and teaching for democracy: our professional obligations’, European Political Science, 19(2), pp. 236-245.

Pithers, R T and Soden, R (2000) ‘Critical thinking in education: a review’, Educational Research (Windsor), 42(3), pp. 237-249.

Roche, M (2016) ‘What is action research?’ in B Sullivan, M Glenn, M Roche and C McDonagh (eds.) Introduction to Critical Reflection and Action for Teacher Researchers, Oxon: Routledge.

Russell, T (2008) ‘How 20 Years of Self-Study Changed my Teaching’ in C Kosnik, C Beck, A E Freese, and A P Samaras (eds.) Making a Difference in Teacher Education Through Self-Study: Studies of Personal, Professional and Program Renewal, Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Samaras, A P (2011) Self-Study Teacher Research: Improving your Practice through Collaborative Inquiry, California: Sage.

Sezer, R (2008) ‘Integration of critical thinking skills into elementary school teacher education courses in mathematics’, Education (Chula Vista), 128(3), pp. 349-363.

Shah, H and Brown, K (2010) ‘Critical Thinking in the Context of Global Learning’ in T Wisely, I Barr, A Britton, and B King (eds.) Education in a Global Space, Edinburgh: IDEAS.

Stupple, E J, Maratos, F A, Elander, J, Hunt, T E, Cheung, K Y and Aubeeluck, A V (2017) 'Development of the Critical Thinking Toolkit (CriTT): A measure of student attitudes and beliefs about critical thinking', Thinking Skills and Creativity, 23, pp. 91-100.

Sullivan, B, Glenn, M, Roche, M, and McDonagh, C (2016) Introduction to Critical Reflection and Action for Teacher Researchers, Oxon: Routledge.

Taşkaya, A and Çavuşoğlu, F (2017) ‘Developing the Critical Thinking Skills in Pre-Service Primary School Teachers: Application of School and Teacher-Themed Movies’, International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 9(3), pp. 842-861.

Westheimer, J (2019) ‘Civic education and the rise of populist nationalism’, Peabody Journal of Education, 94(1), pp. 4-16.

Williams, R L (2005) ‘Targeting critical thinking within teacher education: The potential impact on society’, The Teacher Educator, 40(3), pp. 163-187.

Brighid Golden is a lecturer in global education at Mary Immaculate College, Limerick, and a member of the national Development and Intercultural Education (DICE) project network. Brighid is a trained primary school teacher with experience working in Ireland, England and India. Brighid has a Master’s in International Approaches to Education with International Development from the University of Birmingham, and a PhD in Education from the University of Glasgow which focused on global education within initial teacher education. She also has experience designing and developing teaching resources for primary and post-primary settings in relation to human rights.