Cuba’s Human-Centred Approach to Development: Lessons for the Global North

Development Education and Democracy

Introduction

For more than sixty years, Cuba has been a source of political and ideological contestation from the height of Cold War tension during the Cuban missile crisis to the relentless efforts by the United States (US) to derail its socialist revolution (Bolender, 2010). Cuba’s socialism was ideologically bracketed by Western powers with the satellite states of the former Soviet Union fully expected to implode at the end of the Cold War. While the collapse of the Soviet Union meant severe economic contraction for Cuba with an eighty per cent drop in imports and exports, and a shrinking of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by a staggering thirty-five per cent, the country survived through belt-tightening and innovation such as the introduction of organic farming and use of biomass as an energy source. As Helen Yaffe (2020a) suggests:

“decisions made in a period of crisis and isolation from the late 1980s shaped Cuba into the twenty-first century in the realms of development strategy, medical science, energy, ecology and the environment, and in culture and education”.

Perhaps the key factor in the endurance of the Cuban revolution, again under-estimated by the US and its allies, has been the support of the Cuban people for the revolution and the sacrifices they made particularly during the ‘Special Period in Time of Peace’ introduced in 1991 following the economic crisis. The Cuban revolution could not have triumphed in 1959 without their support and could not have endured for over sixty years without their activism. As Paulo Freire said in Pedagogy of the Oppressed:

“Without the communion which engenders true cooperation, the Cuban people would have been mere objects of the revolutionary activity of the men of the Sierra Maestra, and as objects, their adherence would have been impossible” (Freire, 2005: 171).

This article reflects on some of the key development milestones achieved by Cuba over the past sixty years from the 1961-62 literacy campaign to its successful production of home-grown COVID-19 vaccines and rolling out of a vaccination programme. As Helen Yaffe (2020b) asks:

“Just how can a small, Caribbean island, underdeveloped by centuries of colonialism and imperialism, and subject to punitive, extra-territorial sanctions by the United States for 60 years, have so much to offer the world?”.

A follow-up question could be why have countries in the global North and the international development and development education sectors in Ireland, Europe and elsewhere been so slow to learn from Cuba’s developmental achievements? Cuba’s ground-breaking work in health and education from a small economic base, shrunken further by a sixty-year-old US blockade, suggests that exponential growth is not essential to maintaining a developmental state. What is required is the political will to prioritise social needs rather than objectivise humans as subservient to the demands of the market economy. The article begins with an assessment of the impact of the US blockade on Cuba and argues that this has not prevented Cuba from achieving high level development indicators.

The US blockade of Cuba

The most concerted and sustained effort by the US to topple the Cuban revolution has been Washington’s ‘Embargo on All Trade with Cuba’ - Proclamation 3447 – signed into law on 3 February 1962 by President John F. Kennedy. The embargo or blockade had the aim of ‘isolating the present Government of Cuba and thereby reducing the threat posed by its alignment with the communist powers’ (The American Presidency Project, 2022). This anachronistic relic of the Cold War continues to inform US policy with Cuba, as President Biden, following the lead of his predecessor Donald Trump, has kept Cuba on Washington’s list of ‘state sponsors of terrorism’. Cuba was accused of ‘repeatedly providing support for acts of international terrorism in granting safe harbour to terrorists’ (Philips, 2021); this is despite President Obama’s decision to lift this designation in 2015 and ease the two countries toward greater diplomatic normalisation (DeYoung, 2015).

Cuba estimates the cumulative economic damage caused by the US blockade at $154.22 billion and continues to suffer ‘devastating international financial restrictions’ with most Western banks refusing to process transactions with Cuba because of the blockade’s extra-territorial reach (UN, 2022; Benjamin and Bannan, 2022). The irony for Washington is that despite the aggression of its blockade and its stated aim of Cuban isolation, it is the US that faces an annual humiliation in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) when a resolution titled “Necessity of ending the economic, commercial and financial embargo imposed by the United States of America against Cuba’, is voted on by members. The latest vote, on 3 November 2022, was the thirtieth time this resolution has been supported by the UNGA, and saw 185 countries vote in favour of ending the blockade and only two, the US and Israel, vote against with two abstentions (UN, 2022).

Despite the economic hardship suffered every day by Cuban citizens as a result of the blockade the Trump administration added 200 restrictions on economic activity between the US and Cuba including remittances sent by Cuban-Americans to relatives living in the island (Augustin, 2020). These restrictions have impacted on trade, banking, tourism and travel which are designed to maximise internal pressure on the Cuban government and secure the support of the 1.5 million Cuban-Americans in Florida, a key swing state in US elections (Ibid). Biden’s decision not to remove Cuba from Washington’s ‘state sponsors of terrorism’ list is likely to represent a play for those same votes, placing political efficacy over the humanitarian needs of Cuban citizens. During the pandemic, Cuba’s economic squeeze intensified as tourism was choked off by necessity and the island was denied vital hard currency to buy personal protective equipment (PPE) and medicines. A key element of the US blockade, enshrined in the Cuban Democracy Act (1992), is its extra-territoriality enabling the US to sanction third parties that trade with Cuba (Gordon, 2014: 66). In 2015, for example, the French international banking group, BNP Paribas, agreed to a record $9bn (£5.1bn) settlement with US prosecutors over allegations of trade sanction violations with Sudan, Iran and Cuba (Raymond, 2015).

Marc Bossuyt, from the UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, found that the 1992 Cuban Democracy Act, attempted to turn ‘a unilateral embargo into a multilateral embargo through coercive measures, the only effect of which will be to deepen further the suffering of the Cuban people and increase the violation of their human rights’ (Bossuyt, 2000). Amnesty International has found that the US government is ‘acting contrary to the Charter of the United Nations by restricting the direct import of medicine and medical equipment and supplies, and by imposing those restrictions on companies operating in third countries’ (Amnesty International, 2009: 20). It adds that the US should take ‘the necessary steps towards lifting the economic, financial and trade embargo against Cuba’ (Ibid).

Cuba’s development achievements

According to UN data for 2021, the United States has a mean life expectancy at birth for males and females of 78.8 years, has GDP per capita of $65,133 and spends 19.9 per cent of GDP on healthcare (UN Data, 2022). Cuba has a very similar mean life expectancy of 78.7 with a GDP per capita of $9,295 and spends 11.2 per cent of GDP on healthcare (Ibid). By point of reference, Costa Rica has a mean life expectancy at birth of 80.0 years with a GDP per capita of $12,238 and spends 7.6 per cent of GDP on healthcare (Ibid). These statistics suggest that a high GDP per capita is not a necessary guarantor of a high life expectancy. Granted, life expectancy tells us very little about the quality of life enjoyed by citizens, but statistics from the US Census Bureau for 2021 showed that 11.6 per cent of Americans, or 37.9 million people, were living in poverty, nearly twenty per cent of whom were Black (US Census Bureau, 2022). If we add into this statistical mix that Cuba produces 2.5 carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions per capita (tonnes) compared to 16.6 CO2 emissions per capita (tonnes) in the US (UNDP, 2020) then we can see that the high-growth model of development pursued by high income countries like the US comes at an environmental cost without creating social and economic equality (UNDP, 2020). Fitz (2022), for example, found that between 2019 and 2021, encompassing the worst impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancy in the US plunged almost three years while for Cuba it edged up 0.2 years.

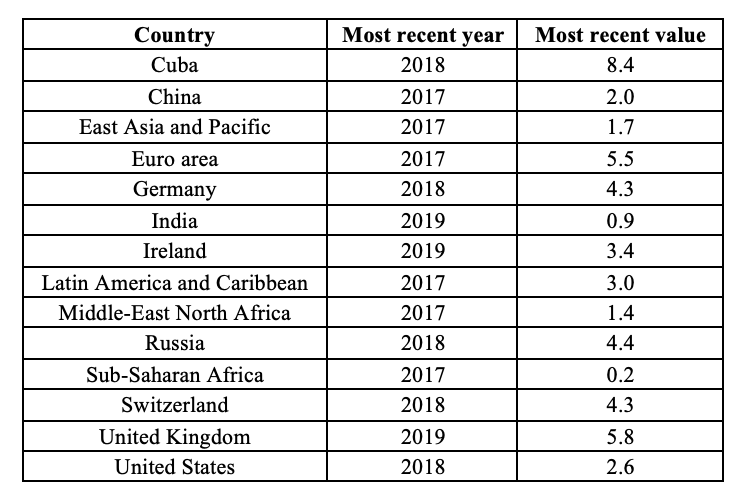

The decline in US life expectancy can largely be attributed to the pandemic and a private health system based on profit, rather than offered as a public service. In Cuba, healthcare is offered to all citizens as a fundamental human right and free at the point of delivery. The contrasting approaches to healthcare resulted in Cuba having eighty-seven COVID-19 deaths by 21 July 2020, when the US had experienced 140,300 (Fitz, 2022). While the US population is thirty times that of Cuba, it had 1,613 times as many COVID deaths (Ibid). This was the result of national planning by the Cuban Ministry of Health built upon six decades of health infrastructure and good practice. By way of example the table below shows the number of Cuban doctors per 1,000 people compared to selected countries and regions. It illustrates the value of prioritising social values and public need rather than modelling the economic system on endless cycles of growth that serve no purpose other than sustaining elite consumption at an enormous ecological cost (Bhalla, 2022).

Table 1: Physicians per 1,000 people (Cuba and selected countries and regions)

Source: The World Bank (2022).

Cuba’s COVID-19 response

Between March 2020 when Cuba initiated its COVID-19 vaccine development and June 2022, the island’s biomedical innovation enabled it to advance five vaccine candidates for trialling with three domestically produced vaccines receiving Emergency Use Authorization (EUA). The vaccines are Abdala (approved in July 2021), Soberana 02 and Soberana Plus which received EUA in August 2021. In September 2021, Soberana 02 and Soberana Plus received EUA for use in the paediatric population and, in October 2021, Abdala received the same authorisation. All of this meant that by June 2022, ninety per cent of the Cuban population had been fully vaccinated, including 97.5 per cent of children over the age of two. By June 2022, Cuba was reporting less than twenty new daily COVID-19 infections and no deaths while globally there were 843,000 new confirmed COVID-19 cases and 1,874 deaths per day, with only sixty per cent of the global population fully vaccinated (MEDDIC, 2022: 2-4). Cuba’s Finlay Institute which developed the Soberana vaccines is rated third out of twenty-six pharmaceutical companies on a ‘Fair Pharma Scorecard 2022’ which ‘ranks Covid-19 medical product developers based on their commitment to human rights principles’ (Rawson, 2022). The scorecard is based on criteria that includes pricing and distribution, technology transfer and open source patents (Ibid). While wealthy countries were accused of ‘vaccine hoarding’ (Costello, 2021) which put millions of lives at risk in the global South, Cuba agreed to share its vaccines and the technology behind them with other low-income countries in the global South including Nicaragua, Vietnam, Mexico and Venezuela. Moreover, Cuba’s vaccines do not require storage at low temperatures, are inexpensive to produce and can be manufactured to scale making them more accessible to low-income countries (Rawson, 2022).

What is evident in Cuba’s domestic capacity to successfully manufacture its own vaccines and roll them out to the overwhelming majority of its population, is a total commitment to public health. Cuba’s home-grown vaccination programme ‘demonstrates the importance of building and nurturing domestic health technology capabilities including ecosystems of suppliers and manufacturers’ (Geiger and Conlan, 2022: 55-56). Cuba’s sharing the vaccines with other countries at cost reflects an internationalism reflected in health ‘becoming a defining characteristic of its revolution’ both domestically and overseas (Feinsilver, 1993: 1). Cuba’s revolutionary leader, Fidel Castro, made a declaration of intent that Cuba would become a ‘bulwark of Third World medicine’ and a ‘world medical power’ (Ibid). The imbalances in vaccine coverage and the lack of solidarity by advanced economies toward countries in the global South was ‘coloured by a colonial legacy’, argued Geiger and Conlan, ‘which substitutes local capacity building in low and middle-income countries with donations’ (2022: 46). The Director-General of the World Health Organisation (WHO), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, pulled no punches when describing vaccine inequity as a situation of ‘vaccine apartheid’ with only four doses per 100 people of COVID-19 vaccine administered in low-income countries by October 2021 compared to 133 doses per 100 people in high-income countries (Bajaj, Maki and Stanford, 2022).

Henry Reeve Brigade

Cuba’s international approach to healthcare long precedes the pandemic, with 400,000 Cuban medical professionals having worked in 164 countries over six decades (Yaffe, 2020b). This health solidarity is best reflected in the work of the Henry Reeve Brigade, an International Team of Medical Specialists in Disasters and Epidemics comprising 1,586 medical professionals, including nurses, doctors and medical technicians dispatched in response to emergency situations wherever they arise. The brigade is named after a Brooklyn-born brigadier-general, who fought and died in 1876 during the First Cuban War of Independence, and was established by Fidel Castro in 2005 to offer assistance to the victims of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. While President George W. Bush rejected the offer of assistance, it’s instructive to look at how Katrina was used by Republican policy-makers to set in train thirty-two neoliberal policies, including the suspension of wage laws and creation of a ‘flat-tax enterprise zone’, while parents were given vouchers to use at for-profit charter schools (Klein, 2007: 410). The Cuban response to the disaster was to offer professional humanitarian assistance while politicians in the US sought to exploit the disorientation caused by the ‘shock’ of the disaster for purposes of privatisation and profit.

The medical missions undertaken by the Henry Reeve Brigade have included the 2014-16 Ebola outbreak in West Africa when 250 medics risked their lives while fighting the virus in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia, (MEDICC, 2017). When COVID swept across the world in March 2020, Cuba sent 593 medical workers to fourteen countries, including Italy’s worst-hit region Lombardy (Petkova, 2020). In May 2017, the Henry Reeve Brigade receive the WHO’s prestigious Dr Lee Jong-Wook Memorial Prize for Public Health ‘in recognition of its emergency medical assistance to more than 3.5 million people in twenty-one countries affected by disasters and epidemics since the founding of the Brigade in September 2005’ (Pan American Health Organisation, 2017).

Yet another major contribution to global medicine by Cuba is the Latin American School of Medicine (LASM) (Escuela Latinoamericana de Medicina, [ELAM]) established in the wake of Hurricane Mitch in 1998 which tore through Central America and the Caribbean causing thousands of deaths and left 2.5 million homeless (Gory, 2015). The mission of the school is to provide a free medical six-year scholarship to students living in marginalised communities in low-income communities in Africa, Asia and the Americas (including the US) who, upon graduating as doctors, pledge to devote their working lives to similarly impoverished communities in need of medical support (MEDICC, n.d.). LASM prioritises female and Indigenous students which prompted Dr Margaret Chan, former Director-General of the World Health Organisation, to say during a visit to the school: ‘For once, if you are poor, female, or from an indigenous population you have a distinct advantage… an ethic that makes this medical school unique’ (Gory, 2015). By the twentieth anniversary of LASM in 2019, 29,000 medical students had graduated from the school, including 182 from the United States (MEDICC, 2019). A grassroots empowerment programme that is tuition-free, LASM has now benefited physicians from more than 120 countries with former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon, saying on a visit to the school, ‘Cuba gives us a lesson of solidarity and generosity’ (Oram, 2018).

Education

From the beginning of the twentieth century, US interventionism in Cuba was given a legislative sheen with the Platt Amendment which enabled Washington, directly or indirectly through proxies, to control the island’s economy and government (Franchossi, 2016). For the Cuban people, this period of neo-colonialism was characterised by poverty and social neglect, particularly in the area of education. Prior to the 1959 revolution, Cuba had one million absolute illiterates, more than a million semi-literate, 600,000 children without schools and 10,000 teachers without work (Correa, 2021). In 1961, Cuba launched a literacy campaign involving brigades of educators with 268,420 members described by the Minister of Education, Ena Elsa Velázquez Cobiella, as ‘a momentous revolution in the educational and cultural order’ (Ibid). The literacy campaign enabled 707,212 adults to learn to read and reduced the illiteracy rate to 3.9 per cent of the total population, overcoming what Fidel Castro described as ‘four and a half centuries of ignorance’ (Ibid). Not content with enabling students to read, the Cuban commitment to education included language schools, education in the community and education services for the disabled, including 1,500 blind students taught to read using braille between 1979 and 1983 (Ibid). Many of the men and women who joined the revolutionary struggle in the 1950s were illiterate peasants or part of the urban poor who used the revolution as a springboard into higher education. Ramiro Abrue joined the revolutionaries in the Sierra Maestra and here describes his upbringing:

“I was born in a distant peasant hamlet, very humble. Our house was made of mud. My dad was a muleteer. He died after my first school year, which was a disaster for a poor peasant family. We had to move periodically, first to the village of Caibarién and then to Havana. We were always on the move. Once we moved six times in a year. My primary and secondary education was completely irregular. The result was that I was a functional illiterate. Thanks to the revolution I could study” (Kruijt, 2017: 46-47).

Ramiro later became Cuba’s liaison with Central American revolutionaries for more than thirty years and went on to hold a doctorate in history. Dirk Kruijt’s (2017) oral history of Cuba captures several similar examples of political literacy combining with educational literacy to support transformative learning.

Education, like healthcare, is free to all Cuban citizens and is a leading employer of women with sixty per cent of the workforce female. There are 10,626 schools servicing a population of eleven million. There are twenty-two universities, of whom fourteen are headed by women who occupy sixty-three per cent of the top university positions (Oxfam, 2021: 53). Among the impacts of the blockade on education in Cuba are the severing of exchange visits made by staff and students to universities in the US and impediments to migrating teaching to digital platforms, particularly necessary during the pandemic. Cuba had to fall back on television to broadcast classes to 1.7 million students (Ibid: 55).

However, one of the towering achievements of Cuba in education has been its adult and youth literacy programme, Yo, sí puedo (‘Yes, I Can’) developed by the Latin American and Caribbean Pedagogical Institute (IPLAC) of Cuba. The programme has been implemented in thirty countries and, to date, 10.6 million people have been made literate, while 1,317 learners are in classes (Correa, 2021). The majority of beneficiaries are in the global South in countries including Venezuela, Mexico, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Mozambique and Angola. One of the beneficiary countries is Argentina which by 2018, had a total of 33,650 graduates with the results of the programme transformative as well as pedagogical:

“because it allows for personal change, self-esteem and the relationship with society. In the four months a physical change is seen, the dress changes, the attitude, becoming aware that a better reality is possible” (Rezzano, 2019).

Climate change

Cuba is one of the few countries to have taken a science-based approach to mitigation and adaptability on the question of climate change. It spent a decade working on a climate action plan called Tarea Vida (‘Project Life’) driven by the urgency of exposure to extreme weather systems such as Hurricane Irma in 2017 which pummelled the island causing extensive damage to settlements and infrastructure (Grant, 2017). Passed by Cuba’s Council of Ministers in 2017, Project Life takes a long view of climate mitigation premised upon practical action and driven by the need to build the resilience of vulnerable communities. The measures included in the climate action plan are: banning construction of homes in vulnerable coastal areas; relocation of populations threatened by flooding; shifting agricultural production away from salt-water contaminated areas; strengthening coastal defences and restoring natural habitat (Stone, 2018). Cuba will be hoping to access support from the Adaptation Fund agreed at COP27 (Worth, 2022) to enhance resilience for people living in the most climate-vulnerable communities like those in close proximity to the thousands of kilometres of Cuba’s low-lying coastline.

Cuba’s average sea level has risen by nearly seven centimetres since 1966 and the annual average temperature has increased since the middle of the last century by 0.9 degrees Celsius. Projections by Cuba’s Ministry of Science, Technology, and Environment (Citma) estimate an average increase in sea level to twenty-seven centimetres by 2050, and eighty-five cm by 2100. Cuba has been modelling the impact of these dramatic rises in sea level and implications for flooding, agriculture, loss of dry land and increase in salinisation (Milán and Del Toro, 2018). The South-Eastern province of Guantanamo has already made the most significant progress to date in actioning the climate plan by reforesting coastal ecosystems, constructing water treatment plants, and promoting environmentally friendly agricultural practices (Ibid). While Cuba has constructed a long-term mitigation plan modelled to the end of this century, like many small-island nations it lacks the capital needed to fully realise its climate targets.

Family Code

Cuba has also been making advances in domestic legislation toward inclusivity and equality. On 26 September 2022, the Cuban people adopted by national referendum a highly progressive Family Code with 67.87 per cent of the population voting ‘yes’ and 33.13 per cent opposing. The referendum followed an extensive consultation exercise involving 79,000 neighbourhood meetings that generated 434,000 proposals and twenty-five versions of the Code before the final draft was agreed and put to a vote. Among the measures agreed in the Code are: the right to marriage, adoption and assisted reproduction for same-sex couples; women’s reproductive rights over their bodies; rights for the vulnerable including the elderly, children, adolescents and the disabled; corporal punishment made illegal with parents now having ‘responsibility’ for rather than ‘custody’ of their children; domestic violence penalties; an equitable distribution of domestic work; and expanded rights for carers (Ramírez, 2022: 15). The emphasis in the Code is on love, human dignity, equality and non-discrimination and backs-up many of the principles enshrined in Cuba’s 2019 Constitution on the idea of equality regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation or gender identity (Ibid: 16). The Code is a rebuttal to homophobia, transphobia and misogyny and the ‘prejudices and stereotypes that are part of the collective imaginary’ (Ibid: 17). Perhaps its biggest achievement is in challenging Cuban patriarchy particularly in the family home through legislation that directly targets gender-based violence, women’s double-shift at home and in the workplace, and the need to share domestic work.

Cuba’s economy

In January 2021, Cuba ended its dual currency system which had seen Cubans use the Cuban Peso and tourists use the convertible CUC which was pegged at 1:1 with the US Dollar. This system had created inequalities in Cuba with those who had access to CUCs through tourism or remittances enjoying a better lifestyle than those depending on salaries in Pesos. The two currencies were unified with the Cuban Peso pegged at twenty-four Pesos to the Dollar. ‘The aim of the reform was to improve the relative position of Cuban peso-earners’, argues Emily Morris, ‘and incentivise import substitution and export growth’ (2022: 18). In order to shield Cubans from the ‘painful adjustment process’ state salaries and social security payments were increased but inflation running at seventy per cent has meant spiralling food prices and a reduction of food imports between 2019 and 2021 of forty per cent (Ibid: 19). One fifth of Cuba’s import expenditure is on food which meant that the dramatic loss of hard currency income caused by the shutting down of the tourism sector during the pandemic hit the economy substantially. On a visit to Cuba in April 2022, I saw currency changing hands on the street with Cuban Pesos trading at much higher rates than the official 14:1 official peg with the US Dollar. My taxi driver from the airport refused to accept Pesos and wanted payment in Dollars or Euros, and this policy was replicated in other tourism services. For the Cuban economy, this appeared to be the deepest crisis since the Special Period of the 1990s. Food shortages and spiralling prices, electricity cuts, lengthy queues at stores, disquiet about the pandemic, the loss of tourism hard currency, the tightening of the blockade by the Trump and Biden administrations, and an over-dependence on imports represented an enormous collective challenge for the island.

Cuba’s highly successful vaccination programme meant that it could open its doors to tourists again in November 2021 and Havana’s international reputation for world-class healthcare meant that tourists had confidence in travelling with safety to the island during the pandemic. Official forecasts suggest that a two-year recovery period will be needed to restore the economy to pre-pandemic levels (Ibid: 20), but a growth rate of four per cent was anticipated for 2022 suggesting that a corner might have been turned (Cordoví, 2021). However, Cuba’s economic turbulence is likely to continue as long as it has to withstand the terrible constraints imposed by the US blockade.

Conclusion

When Jason Hickel introduced the Sustainable Development Index (SDI) as a necessary alternative to the United Nations’ Human Development Index (HDI) (UNDP, 2020), he sought to assess countries on the basis of indices of progress ‘defined less by GDP growth and more by social goals’ (Hickel, 2020a: 1). The HDI ranked countries mostly on the basis of growth measured by GDP per capita whereas the SDI directly addresses the question of ecological sustainability. The SDI used the same basic formula as the HDI based upon life expectancy, education and income but added new indices for material footprint and CO2 emissions. This resulted in a very different ranking to the HDI with the latter headed by countries with high carbon emissions and GDP per capita. The SDI, however, is headed by low-income countries with positive development indicators and low carbon footprints. The top five countries in the 2019 SDI are Costa Rica, Sri Lanka, Georgia, Panama and Cuba (SDI, 2019) which, for development educators, offers an opportunity to explore with learners, avenues to development that are more equitable and sustainable. The HDI, like the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), is framed in the context of development as growth rather than seriously addressing the root causes of poverty, inequality and injustice in the dominant economic paradigm of neoliberalism (Alston, 2020; Fricke, 2022).

This article has suggested that the high-level development achievements of Cuba from a narrow economic base in a wider context of extreme aggression from its near neighbour to the North, offers convincing evidence that the relentless pursuit of growth is not necessary to address the social needs of all citizens and is highly damaging to the natural environment. The concept of de-growth is gaining significant momentum in academia and civil society as a means of containing growth within planetary boundaries and organising society on the basis of sustainability rather than capital accumulation (Hickel, 2020b). Cuba’s remarkable history of six decades of literacy, universal healthcare, community and adult education, and international health solidarity bears the closest of scrutiny. We can now add to that list its momentous advances in biotechnology and climate mitigation under the severest of economic constraints.

This is not to propose Cuba as a cut and paste template for other countries to apply but as a developmental state worth serious investigation by civil society movements, development NGOs, development educators and government ministries interested in sustainability, equity, human dignity and solidarity. Why settle for a state that overuses resources, chews through the planetary boundary, espouses ever ending growth and still fails to meet even the most basic human rights such as health, education, nutrition, housing, employment and inclusivity? Another world is possible.

References

Alston, P (2020) ‘The Parlous State of Poverty Eradication: Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights’, 2 July, Human Rights Council, available: https://chrgj.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Alston-Poverty-Report-FINAL.pdf (accessed 23 July 2020).

Amnesty International (2009) ‘The US Embargo against Cuba: Its Impact on Economic and Social Rights’, AMR 25/007/2009, London: Amnesty International, available: https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/amr250072009en.pdf (accessed 9 December 2022).

Augustin, E (2020) ‘Cubans lose access to vital dollar remittances after latest US sanctions’, The Guardian, 1 November, available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/01/cuba-remittances-us-sanctions-western-union (accessed 8 December 2022).

Bajaj, S S, Maki, L and Stanford, F C (2022) ‘Vaccine apartheid: global cooperation and equity’, The Lancet, Vol. 399, Issue 10334, 16 April, available: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(22)00328-2/fulltext (accessed 23 November 2022).

Benjamin, M and Bannan, N L O (2022) ‘Biden Should Remove Cuba from the Infamous State Sponsors of Terrorism List’, Counterpunch, 28 July, available: https://www.counterpunch.org/2022/07/28/biden-should-remove-cuba-from-the-infamous-state-sponsors-of-terrorism-list/ (accessed 6 December 2022).

Bhalla, J (2022) ‘The 1 Percent Are Many Times Worse Than the Rainforest Wreckers’, Current Affairs, 30 November, available: https://www.currentaffairs.org/2022/11/the-1-are-many-times-worse-than-the-rainforest-wreckers/ (accessed 9 December 2022).

Bolender, K (2010) Voices from the Other Side: An oral history of terrorism against Cuba, London: Pluto Press.

Bossuyt, M (2000) ‘The Adverse Consequences of Economic Sanctions on the Enjoyment of Human Rights, Working Paper prepared for the Commission On Human Rights, Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights’, UN Doc: E/CN.4/Sub.2/2000/33, Geneva: UN Economic and Social Council, 21 June 2000, paragraphs 98-100.

Cordoví, J T (2021) ‘2022. To grow 4%’, Cuba News, 29 December, available: https://oncubanews.com/en/opinion/columns/counterbalance/2022-to-grow-4/ (accessed 13 December 2022).

Correa, Y S (2021) ‘The Literacy Campaign was a cultural revolution’, Granma, 21 December, available: https://www.granma.cu/cuba/2021-12-21/la-campana-de-alfabetizacion-fue-una-revolucion-cultural-21-12-2021-21-12-12 (accessed 6 December 2022).

Costello, A (2021) ‘The richest countries are vaccine hoarders. Try them in international court’, The Guardian, 14 December, available: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/dec/14/richest-countries-vaccine-hoarders-international-court-millions-have-died (accessed 23 November 2022).

DeYoung, K (2015) ‘Obama removes Cuba from the list of state sponsors of terrorism’, Washington Post, 14 April, available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/obama-removes-cuba-from-the-list-of-state-sponsors-of-terrorism/2015/04/14/8f7dbd2e-e2d9-11e4-81ea-0649268f729e_story.html (accessed 6 December 2022).

Feinsilver, J M (1993) Healing the Masses: Cuban Health Politics at Home and Abroad, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fitz, D (2022) ‘Life Expectancy: The US and Cuba in the Time of Covid’, Counterpunch, 26 September, available: https://www.counterpunch.org/2022/09/26/life-expectancy-the-us-and-cuba-in-the-time-of-covid/ (accessed 18 November 2022).

Franchossi, G M (2016) ‘113 years since the Platt Amendment and the betrayal of Estrada Palma’, Granma, 11 March, available: https://en.granma.cu/cuba/2016-03-11/113-years-since-the-platt-amendment-and-the-betrayal-of-estrada-palma (accessed 12 December 2022).

Freire, P (2005) Pedagogy of the Oppressed (30th anniversary edition), New York: Continuum Books.

Fricke, H-J (2022) International Development and Development Education: Challenging the Dominant Economic Paradigm?, Belfast and Dublin: Centre for Global Education and Financial Justice Ireland.

Geiger, S and Conlan, C (2022) ‘Global Access to Medicines and the Legacies of Coloniality in COVID-19 Vaccine Inequity’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 34, Spring, pp. 46-61.

Gordon, J (2014) ‘The U.S. Embargo Against Cuba and the Diplomatic Challenges to Extraterritoriality’, Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, Vol. 36, no. 1, Winter, pp. 63-79.

Gory, C (2015) ‘In Cuba, a free medical education leads to a lifetime of benefits’, Cuba Sí, London: Cuba Solidarity Campaign, available: https://cuba-solidarity.org.uk/cubasi/article/198/in-cuba-a-free-medical-education-leads-to-a-lifetime-of-benefits (accessed 24 November 2022).

Grant, W (2017) ‘Hurricane Irma: Cuba hit with strong winds and heavy rain’, BBC News, 9 September, available: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-41210865 (accessed 12 December 2022).

Hickel, J (2020a) ‘The Sustainable Development Index: Measuring the Ecological Efficiency of Human Development in the Anthropocene’, Ecological Economics, Vol. 167, pp. 1-10, available: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c77afeb7fdcb89805fab2a0/t/5de248f378ecef6237c3f5e7/1575110909448/Hickel+-+The+Sustainable+Development+Index.pdf (accessed 16 June 2020).

Hickel, J (2020b) Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World, London: Penguin.

Klein, N (2007) The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, London: Allen Lane.

Kruijt, D (2017) Cuba and Revolutionary Latin America: An Oral History, London: Zed Books.

MEDICC (Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba) (2017) ‘Cuba’s Henry Reeve International Medical Brigade receives WHO Dr. LEE Jong-Wook Memorial Prize for Public Health’, 26 May, available: http://medicc.org/ns/cubas-henry-reeve-international-medical-brigade-receives-dr-lee-jong-wook-memorial-prize-public-health/ (accessed 24 November 2022).

MEDICC (Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba) (2019) ‘Cuba’s Latin American School of Medicine Graduates Hundreds of New Doctors’, 24 July, available: http://medicc.org/ns/cubas-latin-american-school-of-medicine-graduates-hundreds-of-new-doctors/#:~:text=July%2024%2C%202019%E2%80%94Celebrating%2020,over%2029%2C000%20%E2%80%93%20including%20182%20doctors (accessed 24 November 2022).

MEDICC (Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba) (2022) ‘Cuba’s COVID-19 Vaccine Enterprise: Report from a High-Level Fact-Finding Delegation to Cuba’ (Executive Summary), available: http://mediccreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/MEDICC-Cuba-COVID-19-Vaccine-Executive-Summary_2022.pdf (accessed 23 November 2022).

MEDICC (Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba) (n.d.) ‘Latin American School of Medicine’, available: http://medicc.org/ns/elam/ (accessed 14 November 2022).

Milán, Y R and Del Toro, D G (2018) ‘Climate change brings transformations in Cuba’, Granma, 12 April, available: https://en.granma.cu/cuba/2018-04-12/climate-change-brings-transformations-in-cuba (accessed 12 December 2022).

Morris, E (2022) ‘Cuba’s economic challenges: Dr Emily Morris interviewed by Bernard Regan’, Cuba Sí, Spring, London: Cuba Solidarity Campaign.

Oram, B (2018) ‘The Latin American Medical School’, Morning Star, 24 December, available: https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/latin-american-medical-school (accessed 24 November 2022).

Oxfam (2021) ‘Right to Live without a Blockade: The Impact of US Sanctions on the Cuban Population and Women’s Lives’, May, Oxford: Oxfam International, available: https://www.oxfamamerica.org/explore/research-publications/right-to-live-without-a-blockade/ (accessed 12 December 2022).

Pan American Health Organisation (Organización Panamericana de la Salud) (2017) ‘Cuba's Henry Reeve International Medical Brigade receives prestigious award’, 26 May, available: https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=13375:cubas-henry-reeve-international-medical-brigade-receives-prestigious-award&Itemid=0&lang=fr#gsc.tab=0 (accessed 24 November 2022).

Petkova, M (2020) ‘Cuba has a history of sending medical teams to nations in crisis’, Aljazeera, 1 April, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/4/1/cuba-has-a-history-of-sending-medical-teams-to-nations-in-crisis (accessed 24 November 2022).

Philips, T (2021) ‘Trump administration puts Cuba back on “sponsor of terrorism” blacklist’, The Guardian, 11 January, available: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/jan/11/cuba-us-sponsor-terrorism-blacklist-sanctions-trump (accessed 22 November 2022).

Ramírez, B (2022) ‘Love is the law’, Cuba Sí, Autumn, London: Cuba Solidarity Campaign, pp. 15-17.

Raymond, N (2015) ‘BNP Paribas sentenced in $8.9 billion accord over sanctions violations’, Reuters, 1 May, available: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-bnp-paribas-settlement-sentencing-idUSKBN0NM41K20150501 (accessed 9 December 2022).

Rawson, B (2022) ‘Cuba combats “vaccine apartheid” to protect countries in the Global South against Covid-19’, Food and Health, 19 July, available: https://lacuna.org.uk/food-and-health/cuba-combats-vaccine-apartheid-to-protect-the-global-south-against-covid-19/ (accessed 23 November 2022).

Rezzano, M F (2019) ‘“Yo, sí puedo”, Cuban literacy that changes lives in Argentina’, Cuba in Latin America. Latin America in Cuba, 31 July, available: https://distintaslatitudes.net/historias/serie/cuba/yo-si-puedo-argentina#:~:text=%E2%80%9CYo%20s%C3%AD%20puedo%E2%80%9D%20es%20un,potencia%20relacional%20entre%20ambos%20pa%C3%ADses (accessed 12 December 2022).

SDI (Sustainable Development Index) (2019) available: https://www.sustainabledevelopmentindex.org/ (accessed 13 December 2022).

Stone, R (2018) ‘Cuba embarks on a 100-year plan to protect itself from climate change’, Science, 10 January, available: https://www.science.org/content/article/cuba-embarks-100-year-plan-protect-itself-climate-change (accessed 6 December 2022).

The American Presidency Project (2022) ‘Proclamation 3447—Embargo on All Trade with Cuba’, available: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/proclamation-3447-embargo-all-trade-with-cuba (accessed 6 December 2022).

The World Bank (2022) ‘Physicians (per 1,000 people) – Cuba and selected countries and economies’, available: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.PHYS.ZS?locations=CU (accessed 21 November 2022).

United Nations (2022) General Assembly: 28th plenary meeting, 77th session, 3 November, available: https://media.un.org/en/asset/k16/k16o4lsqf3 (accessed 22 November 2022).

UN Data (2022) available: https://data.un.org/default.aspx (accessed 9 December 2022).

UNDP (2020) ‘Human Development Index Ranking 2020’, Human Development Reports, New York: UNDP, available: http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/latest-human-development-index-ranking (accessed 22 January 2021).

US Census Bureau (2022) ‘Poverty in the United States: 2021’, 13 September, available: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2022/demo/p60-277.html#:~:text=Highlights-,Official%20Poverty%20Measure,and%20Table%20A%2D1 (accessed 9 December 2022).

Worth, K (2022) ‘COP27 Reaches Breakthrough Agreement on New “Loss and Damage” Fund for Vulnerable Countries’, 20 November, United Nations Climate Change, available: https://unfccc.int/news/cop27-reaches-breakthrough-agreement-on-new-loss-and-damage-fund-for-vulnerable-countries (accessed 12 December 2022).

Yaffe, H (2020a) ‘How Cuba Survived’, Tribune, 26 July, available: https://tribunemag.co.uk/2020/07/cubas-model-vindicated (accessed 8 December 2022).

Yaffe, H (2020b) ‘Cuban Medical Science in the Service of Humanity’, Counterpunch, 10 April, available: https://www.counterpunch.org/2020/04/10/cuban-medical-science-in-the-service-of-humanity/ (accessed 18 November 2022).

Stephen McCloskey is Director of the Centre for Global Education and editor of Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review. His latest book is Global Learning and International Development in the Age of Neoliberalism (London and New York: Routledge, 2022).