Deeper Democracy through Community Learning: From Education to Empowerment

Development Education and Democracy

Abstract: Following the assumption that the levels of education and social capital are good predictors of democratisation (Barro, 1999; Glaeser, Ponzetto and Shleifer, 2007), many development agencies have promoted a depoliticised education in the global South toward enhancing the individual skills of citizens who would, in turn, find their own ways to promote democracy and sustainable development in their countries. However, the persistence and resurrection of authoritarianism and unbalanced development in both the global South and North (Diamond, 2015) necessitates revisiting education. Based on our experience and research on the role of learning to reduce regional imbalances and to revive marginalised places, as well as pragmatic planning initiatives in neighbourhood development in Iran, we seek to propose an alternative approach to learning for development. Our alternative approach goes beyond the individual adaptive learning conventionally recommended to the South and proposes experiences of individual transformative and community-based reflexive learning processes that would directly contribute to empowering the local community, building local capabilities, lowering inequalities, and strengthening the foundations of democratic institutions at the local level.

With roots in Freirean critical pedagogical approaches, we articulate learning processes at the individual and community level and the ways in which they lead to transformative institutional change in facilitated planning and development programmes. We believe that this new approach will eventually lead to the empowerment of marginalised parts of society and strengthen democracy at the national level as it results in more diverse and distributed sources of political power across developing societies. We ground our discussion with examples and cases drawn from development practices throughout Iran during the rise of pro-democratic forces before widespread disappointment about electoral democracy paved the way for the extreme right to take over local and national governments leading to the recent countermovement in Autumn 2022.

Key words: Institutional Learning; Reflexive and Adaptive Learning; Community Development; Bottom-up Intervention; Deep Democracy.

Introduction

Increasing inequality has been a long-term global trend (Blanchard and Rodrik, 2021), leading to dire consequences including but not limited to the rise of populism, social polarisation, and reduced trust in democratic institutions (Berman and Snegovaya, 2019; Ignatieff, 2020). Many countries in the global South lack the representative government capable and accountable to identify and solve the problems of inequality and underdevelopment (Andrews, Pritchett, and Woolcock, 2017). Market-based solutions have not produced convincing successes either. In contrast to the promises of the neoliberal doctrine, liberalisation efforts have not channelled capital toward underdeveloped regions with lower production costs (Stiglitz and Lin, 2013) rather it has accentuated inequality (Chancel et al., 2022). The response to government and market failures has been a vague democratisation project that would change the political equilibrium in favour of the left behind places in an unknown timetable (Robinson, 2010).

Current theories of democratisation either framing it as an elitist project with no significant role for the masses (North, Wallis and Weingast, 2009; Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012) or, on the other side of the spectrum, formulating democratisation as a mass grassroots centric project as a chapter in the total social transformation of society (Hardt and Negri, 2005; Purcell, 2013), do not promise to bring positive change to the majority of the South given persistent problems of authoritarianism, especially in the post-Arab Spring outlook. We believe that here lies a crucial conceptual space for learning and an imperative for scholars working on the intersection between education and development. On one side of the spectrum, the second group of theories of change leveraging on grassroots movements face a paradox that society needs to learn in practice to overcome some of the problems impeding collective action and institutionalise their solutions through political parties, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and other civil society organisations. Nevertheless, authoritarian leaders find these entities as existential threats and attempt to prevent these forms of civil activism. At the other end of the spectrum, elitist theories of democratisation face a problem of learning too. They assume that authoritarian leaders somehow learn that it is in their interest to gradually open the political system to more inclusive political participation.

Our alternative focuses on education and learning. But it diverges from the de-politicised formal (Freire, 1970; Kane, 2013) form of education mainly focused on individual skills like Information Technology, foreign languages, and mathematics prescribed by many international development agencies (UNESCO, 2015). These documents produced by development agencies utilise the language of community building to sugar-coat their business-as-usual educational approach and they integrate education into the development of human resources for global value chains of production (Kane, 2008). Furthermore, it is assumed that the newly literate individuals would, in one way or the other, find their own ways to act in solidarity to push for democracy and development. Alternatively, we are talking about experiences of learning that would directly (and not by vague intermediaries, if such an approach bears fruit) contribute to empowering the local community to bring about institutional transformation, building local capabilities, lowering inequalities, and strengthening the foundations of democratic institutions at the local level.

We believe an integral element of any development project should be premised upon Freirean education and learning (Freire, 1970): to recognise different types of knowledge, to promote political knowledge, to encourage dialogue, and to empower critical subjects (Kane, 2013). Our solution for the problems of rising inequality, populism, and a constantly downgrading environment is designing development programmes based on the participation and learning of the local community as the main unit of intervention. But we highlight the processes of individual reflexive learning as well as institutional learning as vital complementary learning processes that should be triggered and nurtured for sustainable social transformation.

We provide evidence from Tehran municipality and the Iranian Ministry of Labor, Cooperatives, and Social Welfare (MLCS) to ground our discussion. Reform in several aspects of urban management and city development was pursued from 2017 to 2021 including a wide-ranging change in favour of facilitation-based community-oriented urban development. Similarly, MLCS led several initiatives, such as sustainable regional employment, and supporting and upgrading the livelihoods of street vendors. A critical reflection on the reasons for the collapse of these progressive initiatives is vital here. We believe that in reflecting upon the link between development and democracy, learning can be a useful mediator. Hence, to facilitate this reflection, we first articulate a conceptual framework to help distinguish between different types of developmental interventions as well as between different types of community-based programmes.

Learning for development: a categorization of the archetypes

Our argument is that community-based initiatives are central to development work that might activate substantial grassroot learning potentials to support democracy. We also claim that initiatives that provide local communities with the opportunity to learn and overcome the problems that impede collective action might be the key to engaging larger parts of society in a broader strategy of development and democratisation. Here, we set out different types of education and learning envisaged by different development approaches to show how community-based learning has been widely neglected by development practitioners and theorists. To begin with and to build a comparative framework, we pose two fundamental questions about the learning approaches attached to development interventions.

‘Who?’ The first question of learning

The first question is regarding the ‘who’; asking about the entity that learns. In response, we distinguish between three scales of learning: individual-level learning, community-based learning, and social learning. An example of the most prevalent instance of individual learning considers the basic computer and language skills prescribed and facilitated by development agencies to provide opportunities for the better-educated individuals to compete in a free (but unfair) labour market; the familiar barometer of neoliberal success. As an instance of social learning, one might consider the gradual transformation of the dress code in Iran over the past three decades and the social acceptance of new forms of Hijab despite the persistence of institutionalised legal regulations, which have fuelled the current uprising in Iran.

For an example of community level learning processes, we can look at efforts to cope with the water scarcity crisis in Iran. First, we can point out the patriarchal proposals coming from the mainstream policy-makers advocating a sharp rise in the price of water to let the invisible hand of the market rearrange the current order of agriculture and irrigation. We use the term ‘patriarchal’ in direct reference to the learning model they have in mind to solve the problem. The learning process they try to activate takes place among the undemocratic circles of decision-makers dominated by the tyranny of experts. This type of learning takes place among a limited group (community) of so-called ‘experts’, deciding on removal of ‘unproductive subsidies’, without any input from the wider local population most affected by these decisions (Fazeli, 2016). On the other hand, environmentalist groups who employed a facilitation-based approach to make bottom-up solutions, designed interventions that encouraged dialogue and cooperation among farmers around Urmia Lake (Northeast Iran) that facilitated a change of economic behaviour, transformation of patterns of cropping and repositioning of these farmers in the value chains based on learning at the community level. But, as the community-based learning was not integrated in a broader social learning process that institutionalised the transformed livelihood at the community level, it fell short in saving the lake in the face of the stronger political economic forces at work. In this example, we see that two modes of learning in the form of community-based collective action and individual entrepreneurial skills complementarily worked to bring about local change. However, this local project did not foster institutional and discursive skills to lead a sustainable transformation.

‘What?’ The second question of learning

The second characteristic of learning that helps distinguish different modes of learning is related to the ‘what’ question, asking about the learning processes activated. In response to the ‘what’ question, the literature in the field of education and development suggests that learning is either: an objective adaptation of the learner to the environment or, in other words, it is behavioural and adaptive; an internal reorientation of internal cognitions, perceptions and discourses which can be labelled cognitive or reflective; or a complicated temporal relation between the internal and external dimensions and is reflexive.

The process of adaptation to responses from the environment by individuals with minimal changes to the scheme or cognitive and social patterns and norms that guide the individuals’ interaction with the environment is defined as adaptive or behavioural learning. This process is theoretically captured with various models and names in the literature, including a ‘process of assimilation’ (Illeris, 2009; Kolb, 1984), and ‘single loop learning’ (Argyris, 1977; Senge, 1990). Reflexive learning can be defined as a change of mental and habitual models in response to reflection by the agent on the adaptive learning cycle. This mode of learning can be traced in the literature as accommodative (Illeris, 2009), transformative (Mezirow, 1991), andragogical (Tennant, 2019), or double loop learning (Argyris, 1977). Cognitive or reflective learning can be described as a change in an individual’s cognition (cognitive frames, frameworks, habits of mind, points of view, and espoused theories) by reorienting cognitive categories without direct relation to the outside world and the adaptation process.

In contrast to reflexive learning, which takes place in interaction with the world and in the course of practice, cognitive and reflective learning is abstracted from action, and is described as being expansive (Engeström, 1987), transitional (Alheit, 1992), and concentrated on the life-world of individuals (Kegan, 1994; Jarvis, 2007). The main difference between reflexive and reflective/cognitive learning is related to the ways in which these mental models are treated in theory and practice: as a stand-alone and separate phenomenon from action and adaptation (in reflective/cognitive learning), or as entangled with action and the adaptive learning processes (for reflexive learning). For instance, within the saffron producing and export cluster in northeast Iran that supplies more than fifty per cent of the world’s exported saffron, adaptive learning limits the scope of action of the businessmen to adapting to local market pricing trends, leaving international trade to Spanish and other players. While a major part of the value of saffron export is related to finding and developing new market channels, the persistence of negative competition (adaptive learning) on price, prevented Iranian actors from opening up trade to new markets in East Asia. This progress was realised by a major revision of mental and habitual models about travel habits, collective marketing, personal investment and consumption, and mutual identity building processes all identified as part and parcel of reflexive learning at the community and individual level (Farahani, 2013).

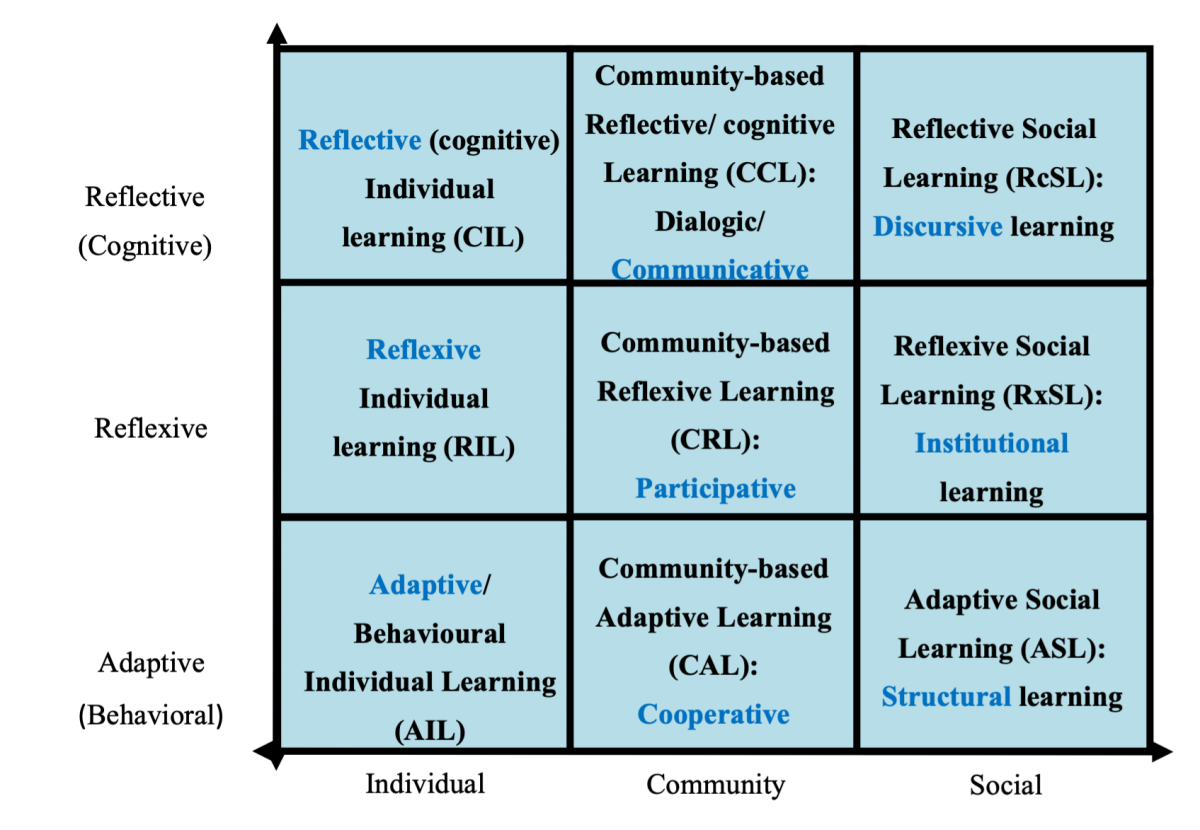

With the two axes (what and who) and three categories for each of them, nine possible learning archetypes (ideal/theoretical types) are developed as depicted in Figure 1 (Farahani, 2021). This categorisation, developed in detail with precise references to educational and developmental literature (Farahani, 2021) helps to make implicit the learning processes embedded in various development paradigms including those that try to overcome feminist, post-colonial, post-development, and structural criticisms of development explicit from a learning perspective. A more precise understanding of the learning components in development practice can lead us toward a more systematic and conscientized embedding of the considerations of learning in design, practice, and monitoring of development projects. Although some elements of this table may seem competing, it must be noted that any developmental programme, when deconstructed from a learning perspective, is composed of several elements of the table with different intensities.

Figure 1: Nine archetypes of learning created by the intersection of two axes (Farahani, 2021)

For example, take the approach of mainstream development practitioners to adopt some of the progressive strategies of empowerment, vocational training, and community development. These neoliberal approaches have been accused of being merely ‘window dressing’ (Tussie and Tuozzo, 2001) and coopting the language of dissent (Roy, 2004). But what makes it distinct from the genuinely progressive schemes? Liam Kane (2008) points out that civil society’s participation in these programmes remains decorative and in practice the governments and powerful international agencies manipulate the process. This is an entry point to adopt the conceptual matrix above. When evaluating the programme design, an important concern would be its potential to enhance the capacities of local communities to work together, and to integrate meaningful participation from the collective body of locals (not from the externally imposed agents), and to take community as the unit of intervention, not the individual. A large body of seemingly progressive community-based interventions, if analysed according to Figure 1, are still circumscribed in targeting the individual rather than triggering participative community-based processes that are entangled with the transformation of shared mental and habitual models among the local community.

To make the point clear, take the neoliberal version of vocational training to reduce poverty and unemployment. This approach tries to stimulate development by activating the adaptive mode of learning at an individual level by developing marketable transferable individual skills. An alternative proposal might diagnose the cause of the problems of underdevelopment as one of innovation; hence it might adopt a different educational strategy that focuses on the entrepreneurial skills of the population, resorting to reflexive individual learning. Further, if the root of poverty is attributed to lack of voice in the national policy-making system, you might resort to strategies that try to initiate a reflective learning process at the national level to address the regional imbalances that are fundamentally different from the first proposition. What distinguishes these proposals is the shade of each learning mode brought forward.

This conceptualisation of learning models in development work also helps to better frame the critics of some of the current depoliticised and under-productive development interventions to draw concrete solutions to contribute in the discourse of ‘empowerment’. Zakaria (2021) argues that the idea of empowerment has become disconnected from the idea of collective political action. She explains that ‘empowerment’ used to revolve around components of power, conscientisation, and agency. Today, however, it has been reduced to mere participation in the economic sphere. Drawing upon Figure 1, we can reformulate the critics of Zakaria as a transition of the empowerment programmes’ design from social and community-based reflexive learning toward programmes focused merely on individual learning.

To revive the emancipatory dimension of empowerment programmes, one should think of how to integrate ever more elements that might strengthen the legal and political capabilities of the local collectives, instead of a sole focus on transferable knowledge gained at the individual level. Mainstream development agencies are focused on the lower row of the table: adaptive individual learning (e.g. how to foster income from chickens) and community-based adaptive learning when it comes to collective skills (e.g. investing in agglomeration effects of business clusters or de-politicised livelihood methods). But our conceptualisation of the learning for development guides us towards the second and third row of the table where a surplus is generated through successful praxis of community, leveraging on the capacities for consensus building, problem solving, advocacy, as well as civil protest and social resistance. This surplus contains collective action capacities and political know-how that goes beyond the algebraic sum of individual learning and economic power of each member of the community.

With this formulation of the link between learning and development, we turn to the second link necessary for our discussion: the link between democracy and learning that will assist us in making the final link between democracy and development with learning acting as the pivot.

Alternative pathways to democracy and their discontents

The proposed quick fixes to liberal democracy (ranked-choice voting, electoral quotas for women, etc.) normally revolve around the same discourse and point of view that produced the crises in the first place, hence fall short of amending the problems facing our democracies (Farahani and Hadizadeh, 2020). Unfortunately, the few radical alternatives of the left aiming to go beyond the tyranny of this pseudo-pragmatism do not seem promising. We identify two strands that try to move beyond conventional representative democracy to critically engage with them from a ‘learning for development’ point of view to draw attention to the third alternative.

The first alternative discourse has roots in Habermas-inspired deliberative democracy. Habermas argues for a true dialogue in an ‘ideal speech situation’ (Green, 1999: 22), in which both sides are ‘freed from the influence of specific problems’ (Habermas, 1971: 73) as the way forward for establishing a more inclusive and better-functioning democracy. Habermas does not explain specifically how the powerless and the marginalised can contribute to these processes of decision-making for the shared resources; rather, his conception of deliberative democracy in practice remains shackled to chains similar to that of the present system delegating power of decision-making to the representatives mostly made up of unaccountable political elites and technocrats. Based on our categorisation, the learning process aiming to be activated through the deliberative approach to democracy advocated by Habermas (Hadizadeh Esfahani, 2013; Holden, 2008; Evans, 2005) is community-based reflective learning (top row on the second column of Figure 1). Here, development subjects are turned into mere absorbers of the learning that has happened for politicians, social scientists, philosophers, and public figures. We believe this to be one of the major shortcomings of the deliberative democracy prescriptions, suggesting that the process of becoming a critical-minded citizen is where the role of education becomes critical. Meaningful participation in democratic dialogue to make policy decisions needs practical skills that are acquired through the processes of learning by doing. But the asymmetry of power in any society undermines the Habermasian dialogue. In addition, opportunities of practical learning at a social level provided through mass movements such as the ones in Iran, Egypt, or Sudan are rare and, arguably, at high costs for the whole of society. Instead, we propose that collective actions in local communities, can facilitate and activate the processes of learning that would serve as a critical element of meaningful participation.

The second alternative to address the ailments of representative democracy is anarchistic, populist, or absolute democracy, that is best formulated in the work of Hardt and Negri (2005). From this perspective, democracy is described as living in a state-less and structure-less world. In this worldview, after the multitude takes over, institutions governing the society are simply turned into tools under the control of the multitude. Thinkers in this framework are primarily concerned with the ways in which hegemony, empire, and apparatuses of capture control not only the coercive power of governmentality but also consent and the governing of the self. This strategy aiming to change the key scenarios and root metaphors (described as hegemonically shaping discourses) of a society by grassroots activism, problematising these discourses, and protesting hegemonic discourse to replace it with a socialist and liberating one serving the interests of the multitudes, mainly focuses on reflective social learning (top right corner of the matrix). Learning in their viewpoint occurs when social truths are destabilised.

Both of these left strategies remain circumscribed to assumptions specific to the global North and fail to provide a roadmap toward democracy in the South. They take the existence of organised popular groups for granted, a phenomenon that Mukand and Rodrik (2020) find peculiar to the industrialised West, hence making their path to democracy inimical to late comers. Rodrik (2016) also notes that due to the differences in structural factors that produce social forces, even when mass political mobilisation takes place in the global South, it would not necessarily revolve around economic disparities aiming to transform the relations around labour rights, taxes, and social welfare; rather the main cleavage is identity. Hence, both strategies might fall short of mobilising social forces towards institutional transformation of the political economy to fight inequality and injustice.

Towards a third alternative discourse of democracy: revisiting learning

The third alternative, on which we try to ground our work, is a pragmatic alternative of creative democracy (Lake, 2017), deep democracy (Green, 1999), and radical democracy (Bernstein, 2010) with roots in the framework of early pragmatist thinkers, notably John Dewey. Dewey develops the idea of democracy ‘as an ethical form of life’, as a normative consequence of humans being more than ‘isolated non-social atoms’ (Bernstein, 2010: 72) which closely resembles Freirean approaches to centring community in social reproduction. He was also critical of ‘democratic elitism’ and the argument that in the face of complexity of social problems and manipulation of individuals by mass media, ‘the wisdom of an intelligentsia’ which has the responsibility to make wise democratic decisions, is necessary. Moreover, he argued that whatever expert knowledge was required for understanding situations, it was not the experts who should take over the debate, and it was up to democratic citizens to judge and decide (Bernstein, 2010: 75). This again has close affinities with Freirean learnings about community knowledge and the process of conscientisation. For Dewey (1960), the ideal of democracy was thoroughly associated with the ideal of community. It is in the ‘deeply democratic community’ that democracy is realised, and this is the point that justifying development relying on community-based learning ties development initiatives into pragmatic democracy. This ideal of democracy relies on the engagement of individuals in reflexive community-based problem solving and learning that is deeply rooted in emancipatory participatory methods of facilitation and community planning (Farahani and Hadizadeh Esfahani, 2020).

While the ailments of representative democracy are real and should be dealt with, the way to progress does not come from either an elitist or a populist route. Rather, the focus should be on creating space for enabling more direct community-based democracy that could provide space for reflective processes on daily practices to make way towards institutional transformation. True, meaningful dialogue that emerges from participation in collective problem solving in community-based planning is one imperative and instrumental for a non-elitist and non-populist approach to practicing deep democracy.

Ailments of the seemingly progressive community-based efforts to strengthen democracy: lessons from Tehran

After setting out our framework, below we briefly present our understanding of the entanglement of democratisation and development in tandem with reflexive participatory community-based learning in our experience in Iran.

Our major learning from the experience of Iran in this framework is that well-designed community-based learning interventions make possible dialogue - as formulated by the pragmatist and emancipatory approach - for progression in democratisation synchronised with development based on participation. Community-based learning and affiliated methods in democracy and development can facilitate the path towards democracy with more inclusive development, and development with deeper democracy. Our experience with the transformation of Razavieh city on the outskirts of Mashhad is a telling example. In 2015, women were initially confined to traditional and religious roles with sewing machines seen as a tool to fulfil their feminine duties at home. This was the entry point for an empowerment initiation, activating a process of community-based learning that started with twenty-five women struggling to support their families’ livelihoods beside the patriarchal roles assigned to them at home. Facilitators provided trainings and connected these women to markets through a community-based learning project grounded in a broader regional development programme that realised the important role that the garment industry could play in job creation in the Mashhad metropolitan Area (including Razavieh). This project, carefully designed regarding the necessary modes of learning in the specific context of Razavieh paved the way for social and political empowerment of women in this region, transforming their role in social hierarchy. After the initial intervention, these women themselves proceeded to deliver twenty workshops (with an average of four employees including men) led by women that became the core of economic life in the city. It also led to the recognition of their socio-economic role in the city, symbolised by an enormous sewing machine sculpture placed in the city’s central square as the signature element of Razavieh.

Furthermore, what became evident in our experiences including in the case of Razavieh is that a clear transformational and progressive vision is needed to guide community-based learning processes. Community-based learning gets derailed from progressive goals in democratisation and development and can turn into small projects without sustainable impacts which can easily fade away. Several of these small initiatives have been carried out in Iran by international, national, and local organisations. But there is a need for broader transformational goals both at the local and societal level that guide community-based initiatives. For example, the anticolonial language of the most progressive community-based initiatives is adopted by the authoritarian quasi-governmental institutions and foundations in Iran to push monumental ‘Mahroomiyat-Zodayi’ (literally meaning ‘removing deprivation’) projects (Karami, 2023). While defined as local projects to ‘empower’ poor communities in theory, they fell short of delivering sustained results in the face of rising poverty (Salehi-Isfahani, 2022). The massive budgets appropriated to these programmes have done nothing more than foster heavy networks of patron-clientelism as they are intentionally detached from the democratic transformative aims of community-building, turning a blind eye to oppressive and disempowering processes that produce mass poverty in the Iranian society in the first place. These community-based development plans, detached from democratic goals, also contribute to the political economy that produced and reproduces poverty by massive wealth accumulation on landgrabs, corruption, and rent-seeking economic activities (Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, 2023).

We have also learned that within communities, community-based learning does not start from the community as a whole; rather it is individual transformational leaders that ignite and motivate community-based learning. The process of learning of such individual leaders (labelled as social entrepreneurs in business and business-related activities) is reflexive individual learning. The activation of individual reflexive learning processes for social entrepreneurs is closely related to activating effective community-based learning if not confused with entrepreneurial rent-seeking hedonistic business promotion. We faced an illuminating instance in a project to have street vendors recognised by the state as formal workers, benefiting from loans, insurance, and social security support. In this experience, a talented young street vendor, who called himself ‘uneducated vendor’ received media training and consultations from an NGO. Trying to represent the interests of street vendors in the media, he acted as a champion to neutralise the propaganda propagated by conservative urban policymakers who resisted recognising this profession (Shamsi, 2017). Nurturing the individual reflexive skills of this social entrepreneur seems much more effective than a superficially benevolent state agent or NGO advocating on behalf of the ‘voiceless’ marginalised community and became instrumental in triggering participative community-based learning among street vendors.

What we have learned more generally and in the face of the broader democratisation movement in Iran is that democratisation endeavours focused on elections without community-based learning and local community empowerment are unlikely to bring about enduring and inclusive development. Rather, they most probably ignite counter-democratic populist movements and halt developmental processes for several years as Iran’s experience in democratic reforms in the early 2000s and most recently, in the past six years, attest (Dabashi, 2011; Mahmoudi, 2011; Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, 2023). The discouraging results of democratisation without community-building is depicted in the experience of city council elections in Iran (Tajbakhsh, 2021). While the reformist government made it a priority to restore city councils as a means for democratic consolidation, the second city council elections became a launch pad for former president, Mahmud Ahmadinejad’s, antidemocratic political career. An elitist electoral approach to democracy (based on reflective learning among elites) has led to inattention to community-based democratic life (reflexive learning among citizens). This arrangement strengthens the propensity for democratisation and development by means of dialogue behind closed doors among elites, which leads to a sense of exclusion and reactionary populist voting in turn. The recent pattern of the rise of the ultra-right in Tehran city council, a city with a population of 8.5 million, attests to this trend (Hamshahri, 2021).

Development without community-based learning and local community empowerment is unlikely to bring about democratisation. Rather, it results in decreased well-being either due to failure to stimulate growth rates necessary for institutionalisation and sustainability of developmental efforts or by the burdens of unbalanced growth: reactionary populist movements for depriving the voiceless, marginalised and under-represented communities. The failed growth resulting from distributional policies relying on various forms of reactionary politics adopted by the mass of people (by electing populists like former president Ahmadinejad) and unbalanced growth dependent on neoliberal growth-oriented policies based on adaptive (individual and societal) learning processes both stifle development (Sarzaeem, 2018).

Conclusion

The narrative of these local communities with their complicated connection to a gradualist blueprint for development and democracy in Iran based on a theory of a learning society might not seem appealing for the mainstream theorists of democracy in prestigious western academia who are fascinated by the contentious politics of the Middle East. In the face of the abyss of another Arab-Spring-style state collapse, we dare to narrate the life story of people like the ‘uneducated vendor’ in Iran as an alternative to adopting a de-politicised stance in doing development work in authoritarian contexts or audacious prescription of Mahammed Bouazizi (the Tunisian street vendor whose self-immolation triggered the Arab Spring uprisings) style struggle for democracy without recognising the risks we might inflict to the target society.

We argue that constant learning in different modes among different segments of society is needed to guarantee the inclusive and meaningful participation of citizens. To make interventions more effective, stable, and sustainable, pro-democracy forces and development practitioners can take advantage of a learning framework that helps improve the design of programmes towards the meaningful empowerment of society. Ailments of the present form of democracy have a direct relationship with decision-making processes behind closed doors. Those most affected by these decisions are the ones least involved in the processes of decision-making and implementation and their political participation is limited to an instance of engineered balloting. We believe the solution might lie in paying more attention to learning that could pave the way for the political participation of ever more sectors of society throughout the year, not just election day. This is where genuine sustainable solutions and innovations are nurtured, not under the shadow of benevolent top-down reformists.

References

Acemoglu, D and Robinson, J A (2012) Why Nations Fail: The origins of power, prosperity and poverty, London: Profile.

Alheit, P (1992) ‘The biographical approach to adult education’ in D O’Sullivan (ed.) Adult Education in the Federal Republic of Germany: Scholarly Approaches and Professional Practice, Vancouver: University of British Columbia, pp. 186-222.

Andrews, M, Pritchett, L and Woolcock, M (2017) Building State Capability: Evidence, Analysis, Action, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Argyris, C (1977) ‘Double loop learning in organizations’, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 55, No. 5, p. 115.

Barro, R J (1999) ‘Determinants of democracy’, Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 107, No. S6, pp. S158-S183.

Berman, S and Snegovaya, M (2019) ‘Populism and the decline of social democracy’, Journal of Democracy, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 5-19.

Bernstein, R J (2010) The Pragmatic Turn, Cambridge: Polity.

Blanchard, O and Rodrik, D (eds.) (2021) Combating Inequality: Rethinking Government's Role, Cambridge: MIT press.

Chancel, L, Piketty, T, Saez, E, and Zucman, G (eds.) (2022) World Inequality Report 2022, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Dewey, J (1960) On Experience, Nature and Freedom, New York: The Library of Liberal Arts.

Diamond, L (2015) ’Facing up to the democratic recession’, Journal of Democracy, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 141-155.

Dabashi, H (2011) The Green Movement in Iran, New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Engeström, Y (1987) Learning by Expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research, Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit.

Evans, P (2005) ‘The challenges of the “Institutional Turn”: New interdisciplinary opportunities in development theory’ in V G Nee and R Swedburg (eds.) The Economic Sociology of Capitalism, pp. 90–116, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Farahani, A F and Hadizadeh Esfahani, A (2020) ‘Exploring possibilities for a pragmatic orientation in development studies’ in J Wills and R Lake (eds.), The Power of Pragmatism: Knowledge production and social inquiry, pp. 244-263, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Farahani, A F (2021) Learning in Development Policy and Practice: Inequality Reduction and Regional Development in Iran, Worcester, USA: Clark University.

Farahani, A F (2013) Socio-reflexive regional learning in the Khorasan (Northeast Iran) Saffron Cluster.

Fazeli, M (2016) ‘My main concern is not the dams, rather it is the development governance system’, Kilid Melli, Vol. 24.

Freire, P (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York: The Seabury Press.

Glaeser, E L, Ponzetto, G A and Shleifer, A (2007) ‘Why does democracy need education?’ Journal of Economic Growth, Vol. 12, pp. 77-99.

Green, J M (1999) Deep Democracy, Community, Diversity, and Transformation, Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Habermas, J (1971) Toward a Rational Society: Student Protest, Science, and Politics, Boston: Beacon Press.

Hadizadeh Esfahani, A (2013) ‘Exploring people-centered development in Melbourne Docklands Redevelopment: Beyond physical development and collaborative planning’, Simon Frasier University.

Hamshahri (2021) ‘Freefall of participation in elections’, Hamshahri Newspaper, 22 June, available: https://bit.ly/3YvVcUh (accessed 20 March 2023).

Hardt, M and Negri, A (2005) Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire, New York: Penguin.

Holden, M (2008) ‘Social learning in planning: Seattle’s sustainable development codebooks’, Progress in Planning, Vol. 69, No. 1, pp. 1-40.

Ignatieff, M (2020) ‘Democracy versus democracy: The populist challenge to liberal democracy’, LSE Public Policy Review, Vol. 1, No. 1.

Illeris, K (2009) Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning Theorists in their Own Words, Abingdon: Routledge.

Jarvis, P (2007) Globalization, Lifelong Learning and the Learning Society: Sociological Perspectives, Abingdon: Routledge.

Kane, L (2008) ‘The World Bank, community development and education for social justice’, Community Development Journal, Vol. 43, No. 2, 194-209.

Kane, L (2013) ‘Comparing “popular” and “state” education in Latin America and Europe’, European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 81-96.

Karami, F (2023) ‘An Investigation on Budget Bill 1402: Anti-poverty’, Research Center of Parliament of Islamic Republic of Iran, available: https://rc.majlis.ir/fa/news/show/1757331 (accessed 30 March 2023).

Kegan, R (1994) In Over Our Heads: The Mental Demands of Modern Life, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kolb, D A (1984) Experiential Learning: Experience as the source of learning and development, Englewood Cliff s, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lake, R W (2017) ‘On poetry, pragmatism and the urban possibility of creative

democracy’, Urban Geography, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 479-494.

Mahmoudi, V (2011) ‘Poverty Change During the Three Recent Development Plans in Iran (1995-2009)’, African and Asian Studies, Vol. 10, pp. 157-179.

Mezirow, J (1991) Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mukand, S W and Rodrik, D (2020) ‘The political economy of liberal democracy’, The Economic Journal, Vol. 130, No. 627, pp. 765-792.

North, D C, Wallis, J J and Weingast, B R (2009) Violence and Social Orders: A conceptual framework for interpreting recorded human history, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Purcell, M (2013) The Down-Deep Delight of Democracy, Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

Robinson, J A (2010) ‘Industrial policy and development: A political economy perspective’, Revue d'economie du developpement, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 21-45.

Rodrik, D (2016) ‘Is liberal democracy feasible in developing countries?’, Studies in Comparative International Development, Vol. 51, pp. 50-59.

Roy, A (2004) The Chequebook and the Cruise Missile, London: Harper Collins.

Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, E (2023) ‘Iran’s Uprisings for “Women, Life, Freedom”: Overdetermination, Crisis, and the Lineages of Revolt’, Politics, Goldsmiths University of London.

Salehi-Isfahani, D (2022) ‘The Impact of Sanctions on Household Welfare and Employment in Iran’, Washington, DC: School of Advanced International Studies.

Sarzaeem, A (2018) Iranian Populism; Analysis of the Quality of Governance of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad from an Economics and Political Network Perspective, Tehran: Kargadan Press.

Senge, P M (1990) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, New York: Doubleday.

Shamsi, A (2017) ‘The most educated uneducated vendor’, Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, 27 August, available: https://telewebion.com/episode/0x1b4a0e9 (accessed 3 April 2023).

Stiglitz, J and Lin, J (2013) The Industrial Policy Revolution I: The Role of Government Beyond Ideology, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Tajbakhsh, K (2021) ‘The Political Economy of Fiscal Decentralization under the Islamic Republic of Iran’, The Muslim World, Vol. 111, No. 1, pp. 113-137.

Tennant, M (2019) [1998] Psychology and Adult Learning: The role of theory in informing practice, Abingdon: Routledge.

Tussie, D and Tuozzo, M F (2001) ‘Opportunities and constraints for civil society participation in multilateral lending operations: lessons from Latin America’ in M Edwards and J Gaventa (eds.) Global Citizen Action, Colorado: Lynne Reinner Publishers, pp. 105–120.

UNESCO (2015) Education 2030: Towards inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning for all, Paris: UNESCO.

Zakaria, R (2021) Against White Feminism: Notes on Disruption, New York: Norton Company.

Alireza Farahani is an urban/regional development practitioner focusing on facilitation-based planning. He received his Ph.D. in Geography from Clark University. Currently, he is working at Sharif University of Technology and other development institutes in Iran for entrepreneurship and business development.

Behnam Zoghi Roudsari is a researcher and policy analyst at Development Studies Center at ACECR in Tehran. He has an extensive record in the field of social policy and welfare, particularly in cooperation with MCLS. He also contributes to social policy debates in public media.