Addressing the Complexity of Contemporary Slavery: Towards a Critical Framework for Educators

Abstract: Many significant global challenges are embedded within social, economic and political systems that transcend national borders (Drinkwater, Rizvi and Edge, 2019: 5). One issue that sits at the intersection of these transnational processes is slavery. Mainstream analyses tend to present slavery in two distinct phases: ‘historical’ slavery as a legal institution abolished in the nineteenth century; and ‘new’ (Bales, 2004) or ‘modern’ slavery (Kara, 2017) as a separate phenomenon, which is primarily associated in the policy literature with criminality in the global South. In these ways slavery is frequently de-coupled from the transnational systems that have shaped and continue to shape it. Recent global events involving the removal of statues have renewed focus not only on the historical legacies and contemporary manifestations of slavery, but their connections to transnational systems. While there is a need for education to explore historical slavery there is a pressing need to consider the contemporary slavery, and the relationships between these forms (Quirk, 2009). This article proposes a framework of critical development education and history education, across conceptual, didactic, affective and active domains to support educational practices that challenge dominant Eurocentric discourses to address the complexities of contemporary forms of slavery.

Keywords: Contemporary Slavery; History Education; Critical Development Education; Historical Enquiry; Historical Consciousness; Transnationalism.

Introduction

Transnationalism is described as the ‘social, economic and political connections between people, places and institutions’ (Drinkwater, Rizvi and Edge, 2019: 5), and is also recognised as global interconnectedness. Whilst global movements of people and ideas offer potential for the positive transformation of societies, there is recognition that transnational processes are often historically connected to violence and inequity. Slavery, in both in its historical and contemporary forms, is a transnational issue (Quirk, 2009; Kotiswaran, 2019) that interconnects in complex ways with a range of socio-economic, institutional, political and environmental processes (Van den Anker, 2004). Keogh, Ruane and Waldron correctly assert that ‘one of the most effective weapons for modern day abolitionists is education’ (2006: 13). Nevertheless, the complex and politically charged relationship between slavery and issues like neoliberal globalisation, development, racialisation and migration make it a daunting subject for educators.

This article identifies three particular challenges for educators in addressing this significant global development issue. First, due to the dual emergence of a transnational global governance regime around human trafficking and renewed intellectual output regarding ‘modern slavery’, the issue was framed through the lens of criminal justice and security, associated mainly with the global South. Second, contemporary slavery was presented in individualised terms, decoupled from the structural and societal issues with which it interconnects. Finally, analysis of contemporary slavery has failed to adequately engage with historical slavery and its legacies. Here we propose methods for addressing these complexities.

Development education (DE) is recognised, in its more critical forms, as a transformative educational process which seeks to foster understanding of local and global issues, meaningful reflection on global justice, and informed action to challenge inequity. Critical development education (CDE), when framed through the lens of historical enquiry (HE), can help learners interrogate the roots of contemporary slavery. The first section presents an overview of the literature exploring the emergence of contemporary slavery as a global development issue, highlighting the contentious conceptualisations of the issue that frame how it is acted upon. The article then provides a critical analysis of Andreotti’s (2006) typology of ‘soft’ versus ‘critical’ DE approaches before considering the implications of this model for education about contemporary slavery. To conclude, we present a pedagogical framework that draws upon critical approaches such as CDE and HE to support educators in planning for and teaching issues of contemporary slavery.

Contemporary slavery: a complex global development issue

Contemporary slavery has emerged as a significant global development issue in the 21st century. Under the guise of ‘modern slavery’, it has been incorporated into the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals, adopted by bodies like the International Labour Organisation (ILO) and International Organisation for Migration (IOM), and enshrined in national legislation, notably in the UK. Meanwhile, a cohort of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and ‘philanthro-capitalist groups’ use their influence to continually focus public attention on the issue (Kotiswaran, 2019). The renewed interest in slavery came initially as a surprise, as many assumed that it had disappeared following legal abolition in the nineteenth century. However, a ‘global sea change’ in anti-slavery activism occurred in the mid-1990s that brought the issue back in from the margins (Quirk, 2011: 158).

The origins of this remarkable shift lay in concerns about migration and borders in the wake of globalisation (Ibid.; Kotiswaran, 2019). In 2000, the concept of ‘human trafficking’ was codified by the UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, which has had ‘phenomenal’ levels of state ratification (Kotiswaran, 2014: 36). While the Protocol is primarily a ‘law enforcement instrument’, its inclusion of the ‘three P’s’ (Prevention, Protection and Prosecution) also reflects the influence of human rights principles (Plant, 2015: 154). Nevertheless, in practice, the early focus of the Protocol was trafficking for sexual exploitation (Ibid.; Kotiswaran, 2014) that manifested as a ‘moral crusade’ against prostitution (Bélanger, 2014: 89).

The codification of human trafficking coincided with interest in ‘new’ (Bales, 2004) or ‘modern’ (Kara, 2017) slavery. Most discussions of this topic begin with scholar-activist Kevin Bales, whose influence is widely acknowledged (Issa, 2017; O’Connell Davidson, 2015; Quirk, 2011). Bales’ most distinctive proposal is the contemporary ‘disposability’ of labour. In this scenario of ‘big profits and cheap lives’ (2004: 4), Bales asserts that ownership is no longer required or even desirable given the abundance of low-cost labour; what is instead required is effective control, which is frequently temporary. While Bales refers to structural issues that create surplus labour (corporate power, land ownership, state policy), his overwhelming focus is on the point of exploitation between ‘slaveholder’ and victim. In this way, Bales presents slavery as a ‘residual’ phenomenon caused by exclusion from global markets (Phillips and Sakamoto, 2012: 296), an ‘anachronism’ to be tackled via economic modernisation and targeted laws (O’Connell Davidson, 2015: 57).

In spite (or perhaps because) of these characteristics, Bales’ conception of slavery ‘found a receptive audience among political elites’ (Quirk, 2011: 158). In particular, this formulation was a good ‘fit’ with human trafficking. The dual emergence of these concepts meant that ‘modern slavery’ became inextricably linked to a criminal justice approach (Plant, 2015). Following Bales’ alliance with the Walk Free Foundation and the creation of the Global Slavery Index in 2013, these ‘new abolitionists’ – an ‘uncomfortable’ coalition of aid agencies, human rights activists, religious groups and ‘neoliberals’ (Murphy, 2019: 6-7) – extended their influence to national legislation and UN bodies (O’Connell Davidson, 2015). Over time the sector has expanded its focus to labour trafficking, a process some view as ‘exploitation creep’ (Chuang, 2014), but which is facilitated by the ‘complex and ambiguous definition’ of trafficking (Gallagher, 2017: 104).

In this context, other international law concepts have also been brought under the ‘umbrella’ of ‘modern slavery’. These include the ‘slavery-like practices’ – among them debt bondage, serfdom, and servile marriage – outlined in the 1956 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery. Furthermore, Allain (2017) has argued that the 1926 Slavery Convention definition of slavery – widely understood then and since as referring only to chattel slavery (Quirk, 2011: 145) – may be re-interpreted to incorporate the ‘modern’ concept of effective control (Allain, 2017).

Similarly, forced labour – first elaborated in 1930 as a ‘modest commitment’ to suppressing state-directed labour (Quirk, 2011: 104) – has been refined to bring it into alignment with trafficking (Plant, 2015), culminating with the ILO’s adoption of ‘modern slavery’. However, this has led to a disjuncture between the concept and its application (Lerche, 2007). For example, the ILO presents forced labour as the ‘antithesis of decent work’, noting the existence of a continuum of exploitation (2009: 8-9). In practice, however, it is ‘embedded’ in a criminal law approach (Fudge and Strauss, 2017: 538) that privileges coercion by ‘force, threat and violence’ (Kotiswaran, 2014: 372). Social issues like discrimination on grounds of ethnicity, class, immigrant status or gender are re-imagined as individual ‘risk factors’; while economic coercion is ruled out entirely (LeBaron, 2020: 41). This ‘cocooning’ of forced labour renders it ‘safe for governments and international organisations’ (Lerche, 2007: 431).

Despite its legal foundations and prominence, ‘modern slavery’ remains notoriously ‘slippery’ and contested (LeBaron, 2020: 7). Indeed, mainstream approaches have generated a ‘wealth of critical scholarship’ focussed on its conceptualisation and operationalisation (Natajaran, Brickell and Parsons, 2020: 2). According to LeBaron’s overview, this framing: obfuscates root causes; provides ‘cover’ for anti-feminist, anti-immigration and pro-business policies; reflects western paternalism; de-politicises labour exploitation; and disempowers workers (2020: 7-8). For LeBaron, those who use the term ‘tend to place way too much emphasis on criminal justice solutions’ (Ibid.: 8). Other scholars claim that the ‘powerful’ anti-slavery lobby promotes an individualised view of exploitation that exists ‘outside the purview of state scrutiny and market capitalism’ (Natajaran, Brickell and Parsons, 2020: 3). For example, Bales and others characterise modern slavery as the ‘dark underworld’ of the global economy but fail to make any causal links (Lerche, 2007; LeBaron and Phillips, 2019). This approach has also been criticised for analysing slavery in a ‘historical vacuum’ (Quirk, 2009: 114).

By contrast, the critical approach adopts the broader category of ‘unfree’ labour (Fudge and Strauss, 2017; Natajaran, Brickell and Parsons, 2020). The reasons for this are twofold. Firstly, it is claimed that the slavery frame tends to ‘depoliticise’ exploitation by focussing on an individualised relationship of exploiter/exploited rather than difficult issues of consent and agency (O’Connell Davidson, 2015). Secondly, critics allege that the metaphor of slavery promotes an ‘implicit dichotomy’ between freedom and enslavement (Natajaran, Brickell and Parsons, 2020: 2-3). Instead, it is argued that exploitation should be conceptualised as a ‘continuum’ (Ibid.) or ‘spectrum’ (Fudge and Strauss, 2017). Other issues highlighted by the critical literature - such as the criminal justice approach, the conflation of trafficking and people smuggling, and the portrayal of corporations as ‘heroes’ (LeBaron, 2020: 9) - derive from the operationalisation of a particular version of ‘slavery’ rather than the term itself.

The critical school represents a ‘useful corrective’ to the hegemonic conceptualisation (Kotiswaran, 2019: 379), but has its shortcomings. Firstly, it adopts a similarly ‘ahistorical’ approach (Lerche, 2007: 433-435), prioritising ‘abstract’ debates on whether unfree labour is ‘capitalist’ (LeBaron and Phillips, 2019: 2). Secondly, notwithstanding ‘fierce debates’ over terminology, almost no-one denies the existence of widespread forced labour and exploitation in practice (Murphy, 2019: xi). While arguing for deeper structural reforms, the ‘scepticism’ of critical scholars toward international human rights law (Kotiswaran, 2019: 379) means it offers little to those actually in conditions of bondage (Quirk, 2011: 206). Finally, some have questioned its relevance to the developing world, where informal labour is the norm, and the impacts of neoliberalism are heterogeneous (Kotiswaran, 2019).

What does this mean for development educators? On one hand, contemporary slavery is a troubling global phenomenon. While data on prevalence is contested, the severity of the human suffering linked to this phenomenon makes it a serious cause for concern (Crane et al., 2019: 88). This is not an issue that educators should ignore. On the other hand, slavery is a challenging topic, raising issues of historical and contemporary justice; legacies of colonialism, racialisation and discrimination; and questions about the meaning of freedom and ‘development’. The importance of addressing these complexities is emphasised by the global movement around the toppling of statues and the debates about racism and colonial legacies it sparked. The geographic spread of the protests and range of figures involved – from legal slaveholders to architects of contemporary slave systems like King Leopold II to colonisers like Columbus – speak to the transnational nature of these interconnections across time. As Quirk (2009: 115) notes: ‘Slavery has always been a global issue. It should be taught as a global issue’.

Critical development education

Development education (DE) is a process which can support the development of knowledge, understanding, skills and values allied to an interrogation of many of the processes associated with transnationalism. Recent research has considered the extent to which DE approaches meet their transformative ends. Drawing on post-colonial theory, Andreotti’s (2006) ‘soft versus critical’ framework presents a multifaceted framing of DE, offering two distinct interpretations. Soft forms of DE identify poverty and helplessness as problems to be solved by individuals compelled to act out of a sense of common humanity. This message is simple and easy to accept (Bryan, 2012), however, Andreotti makes a strong case for a critical DE (hereafter CDE), rooted in the concepts of justice and equality, where the principles for change move from universalism to reflexivity, dialogue and an ethical relation to difference.

Andreotti (2006) makes reference to the importance of critical historical perspectives on the concepts of imperialism, north-south relations and universalisation, which can underpin action through CDE. This compelling assertion raises questions as to how history education and CDE may support critical engagement with contemporary slavery, particularly as the relationships between DE and other educational fields have often been neglected (Bourn, 2008). Andreotti’s (2006) framework is regarded as a seminal contribution to the field (Bourn, 2020; Hartung, 2017), challenging the moral frame through which DE is explored and the assumptions that dominate current approaches. However, this framework has also been critiqued for presenting DE approaches as an either/or option, denying nuances and possible approaches between both (Hartung, 2017). Andreotti has stated that the soft versus critical frame is not necessarily about either/or, but both and more (Andreotti and Pashby, 2013). Indeed, Bourn (2015) suggests that softer forms of DE are a starting point for educators and learners, presenting DE as a learning process that can and should play a role in bringing participants along a more critical path.

Cognisant of these criticisms, but open to the potential of the framework to offer an important critical perspective on educational practice, this article considers how educational approaches which address the theme of contemporary slavery can be structured in a manner which promotes the more critical dimensions of DE, and which interrogate the connections ‘between the individual and personal, from the local to the global’ (Bourn, 2008: 18). These connections, particularly in relation to the concept of slavery, also transcend time and, as such, the article also considers how a focus on contemporary slavery illuminates the potential consonance of DE and history education in addressing complex global issues.

Towards a framework for critical development education through history education

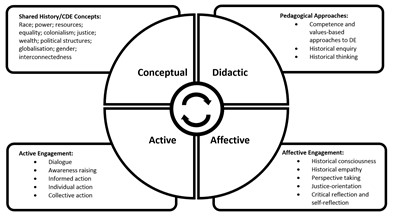

Derived from an analysis of debates within the field of contemporary slavery, against a combined backdrop of Andreotti’s (2006) model and educational practice in the fields of history education and DE, this article proposes a framework for a critical approach to contemporary slavery. Comprised of four interrelated dimensions, the framework (Figure 1) identifies a series of key concepts which may underpin an educational enquiry in this area, the didactic or pedagogical processes which may frame this enquiry, the affective aspects which shape associated learning, and the action-orientations which may guide this process. Whilst a full unpacking of this framework is beyond the scope of this article, the following sections give particular consideration to the conceptual and didactic dimensions of educational approaches to addressing contemporary slavery.

Figure 1: A Framework for planning and teaching CDE

Conceptual connections across time

History education is frequently used to provide deeper context to the legacies of slavery (Klein, 2017), yet there is also a need to consider the contemporary elements of slavery and the relationships between the historical and modern forms (Quirk, 2009). History lessons on the subject of slavery are often chronologically, geographically and thematically limited (Armstrong, 2016) and predominantly focus on the factual aspects of the transatlantic slave trade, avoiding other time periods and regions. Such narrow coverage can lead learners to the conclusion that slavery was a feature of the past, was confined to the continents of Africa and North America and ended when the transatlantic trade was criminalised and slavery abolished (Blum, 2012). HE, when framed through the lens of CDE, can help learners not only make connections between past and present forms of slavery, but can allow them to connect to the global legacies of slavery. Furthermore, this approach enables educators to address the didactic, affective and active domains that must be stimulated to explore concepts such as racialisation, justice, inequality, power and colonialism across place and time.

For example, Quijano’s concept of ‘coloniality of power’ (2000) – a key influence on the work of Andreotti (2011) – asserts that the conquest of the Americas led to the articulation of the labour force with the singular aim of producing commodities for the world market. The exploitation inherent to this system was justified by a process of racialisation whereby each form of labour control – slavery, servitude, wage labour – was associated with a particular ethnicity. According to Quijano (2000), the power of racialisation lives on beyond the end of colonial rule and the abolition of slavery, as evidenced by the persistence of non-wage labour among groups viewed as ‘inferior’. Another approach focuses more on ‘poverty and class politics’ (Munck, 2014: 200). For example, the contemporary privatisation and enclosure of lands in countries like Brazil may be viewed as part of a capitalist process of ‘accumulation by dispossession’ (Harvey, 2005). The reference to Marx’s ‘primitive accumulation’ highlights the similarities between contemporary and historical events, such as the ‘enclosures movement’ in Europe that privatised common lands and pushed peasants into serfdom (O’Connell Davidson, 2015: 59-60).

This lens shifts the focus from exploring narratives about historical slavery to deconstructing the institutional discourses and concepts that contributed and continue to contribute to multiple forms of slavery. In order to understand both the ideologies that underpinned past actors’ thinking and the continuities and discontinuities that shape actions today, it is essential that learners recognise that many historical sources represent Eurocentric discourses rather than those of the disenfranchised or displaced.

Conceptual connections between the individual and the structural

A CDE perspective demands that we engage with the complex inequitable structures that create the conditions within which slavery and exploitation flourish in Ireland and elsewhere. This may be reflective of the movement away from understanding slavery solely as an issue of criminality toward one focused on national and global structures and institutions. For example, Andreotti’s framework and an engagement with post-colonial ideas should lead educators to consider alternatives to the modern slavery/human trafficking/forced labour framework advanced by the United States (US), United Kingdom (UK) and multilateral organisations. India and Brazil stand out in this regard.

The issue of bonded labour was largely overlooked by nineteenth-century abolitionism (Quirk, 2011: 69). Instead, it was left to the postcolonial Indian state to tackle via ground-breaking legislation combining criminal and labour laws (Kotiswaran, 2014: 382-385). Furthermore, this broad approach was underpinned by creative Supreme Court rulings during the 1980s. One key judgement pointed to power asymmetries between employers and workers, holding that labour undertaken due to a lack of economic alternative could be considered ‘forced’ (Ibid.: 389). However, this interpretation was rejected by the ILO (2009). The Brazilian case involved social, labour and religious activism inspired by liberation theology and human rights, but also by Brazil’s history of slavery (Rezende and Esterci, 2017). Activists consciously adopted this language in creating a ‘political category’ to confront powerful vested interests, including military dictatorship, agribusiness and transnational corporations (Ibid.). This led in 1995 to the creation of a new concept of ‘slave labour’ that went beyond the ILO’s narrow view to encompass attacks on human dignity (Ibid.: 83). Evidence from Brazil reveals the importance of contemporary slavery to the global economy (Sakamoto, 2020) and its system is viewed as an ‘indictment’ of capitalism (Issa, 2017: 103).

Similarly, a CDE approach goes beyond institutions and individuals to consider the belief systems that underpin both historical and contemporary slavery (Andreotti, 2006). A key consideration here is the issue of racialisation and its legacies. Much of the framing around human trafficking or modern slavery emphasises their largely de-racialised nature, advancing the claim that ‘anyone’ can be trafficked or subjected to conditions of slavery. For example, a new campaign launched in Ireland by the Government of Ireland in alliance with the IOM is entitled ‘Anyone Trafficked’. Bales notes that the key distinction between exploiter and exploited today is ‘wealth and power’ rather than ethnicity (2004: 17). Although contemporary slavery is not expressly racialised, in practice institutional discrimination based on racialised categories renders specific groups more vulnerable to poverty and exploitation (Van den Anker, 2004: 19). In Brazil, for example, official data reveals that the majority of the 54,000 people found in contemporary slavery since 1995 were black, a fact Sakamoto (2020) attributes to the ‘incomplete abolition’ of slavery and failure to achieve real inclusion.

Conceptual connections from global to the local

A focus on structural issues also recognises that whilst we are all interconnected, the nature of these connections is shaped by power relations that underpin both local and global inequality. One example of these dynamics is Ireland’s fishing industry. In 2015 news reports detailed extensive labour exploitation, including trafficking and forced labour, on Irish trawlers. Migrant workers from Africa and Asia were confined to their boats, received less than half the minimum wage, and were forced to work up to 20 hours a day (MRCI, 2017). Rather than equalise rights, the Irish state introduced an ‘Atypical Worker Scheme’ that tied migrants to employers, deepening unequal power relations (Ibid.). Following a legal challenge and an ‘exceptional rebuke’ from four UN Special Rapporteurs (Lawrence and McSweeney, 2019), the state was forced into an embarrassing climb-down. Nevertheless, the issue precipitated a startling fall by Ireland in the US State Department’s Trafficking in Persons Report, from Tier 1 in 2017 to Tier 2 Watchlist in 2020 – the only western European country at this level. While the report emphasises the need for convictions, a critical approach might link this outcome to Ireland’s insertion into the global economy. As Kirby and Murphy note, the removal of rights and protections from non-EU workers, increasing their exposure to exploitation, was a policy choice driven by a ‘neoliberal fixation’ on limiting state intervention, delivering migrants ‘to the mercy of the market’ (2007: 14).

Bourn (2014: 14) suggests DE should encourage ‘the learner to make connections between their own lives and those of others throughout the world’. In addition to the connections this article has already explored, the literature in this area reveals that the wider network of responsibility towards contemporary slavery must include interconnections to those global issues that increase its likelihood of occurring. This more holistic conceptualisation points in turn to a broader suite of methods to prevent foreseeable harms. For example, the literature highlights the link between land ownership and labour availability, as landless workers are more easily exploited (Quirk, 2011: 121). In places like Brazil, the role of export-oriented agriculture in displacing peasant and indigenous communities is clear (Phillips and Sakamoto, 2012: 306; Sakamoto, 2020). Rather than a by-product of disembodied processes of ‘modernisation and globalisation’ (Bales, 2004: 13), this rush to ‘occupy’ the Amazon and ‘usurp’ communities was incentivised by the state and seized upon by big business (Rezende and Esterci, 2017: 79). Many members of these displaced communities were pushed into contemporary slavery, forced to enclose those same lands so agribusiness could export crops like soy and cotton (Sakamoto, 2020).

These transnational interconnections include the nexus between slavery, the environment and climate change. A mainstream approach links increased deforestation, emissions and coerced labour to consumer demand for forest-risk commodities. To quote Bales: ‘there is no secret to the engine driving this vicious cycle. It is us – the consumer culture of the rich north’ (2016: 8). Framed predominantly as an issue of ‘criminal slaveholders’, Bale’s solution is simple: end slavery (Ibid.: 10). Consumers in the North are presented with a ‘win-win’ scenario: we can absolve our guilt by ‘saving’ people from slavery without impacting ‘our lifestyles or the economy’ (Ibid.: 118). However, a critical approach goes deeper to examine the impacts of neoliberalisation and global governance that empower corporations to exert downward pressure via supply chains, incentivising sub-contracting and labour exploitation that in turn damages the environment (LeBaron, 2020: 73-76). This instrumental power interacts with structural processes of exclusion and deepened precarity, including: landlessness; a lack of decent work and basic services; water, air and soil pollution; and climate change itself. These factors combine to render traditional livelihoods unsustainable, pushing many of the world’s poorest citizens to migrate in precarious conditions (Bond DEG, 2020).

Didactic approaches to CDE

There is a need for DE to move beyond content-based didactic approaches, based on the factual presentation of global issues such as contemporary slavery to consider both competence-based and values-based approaches (Tarozzi and Mallon, 2019). The former is concerned with the development of skills such as ‘critical thinking, finding creative solutions or dealing with complexity and ambiguity’ (Ibid.: 120), while the latter supports a reflection on the values and beliefs which underpin learners’ attitudes, understandings and actions in this regard (Ibid.). As such, active learning methodologies remain important teaching strategies, where learners have the opportunity for discussion, dialogue and reflection on the issue of contemporary slavery.

Drawing on Bourn (2014), a pedagogical framework for exploring contemporary slavery could include fostering a sense of global outlook (and responsibility) towards the issue, nurturing a belief in social justice and equity, developing a commitment to reflection and dialogue, and supporting a recognition of power and inequality within the world, and across time. With a similar concern for the relationship between the past and present, Diptée (2018) contends that there needs to be greater consideration given to how society engages with ideas about slavery’s past that have the capacity to inform present attitudes. Uncomplicated and mythologised narratives that served well in centuries-old debates against slavery are no longer sufficient (Ibid.). Educators and learners need to ask critical questions to explore not only past legacies but also those that continue to hold influence in the present.

HE is a pedagogical approach to teaching that places the learner, their questions and their ideas, at the centre of the learning experience. In contrast to traditional forms of history teaching in which learners consume historical information through uncritical use of textbooks, HE allows learners to engage in the process of asking critical questions, analysing evidence to answer those questions and synthesising their own research (Barton and Levstik, 2004). HE draws on the disciplinary concepts associated with historical study that stem from the historical method. These concepts collectively allow learners to think historically and enable them to analyse evidence, explore change and continuity, interpret cause and effect, and understand how to evaluate historical claims in order to create their own evidence‐based interpretations (Cooper and Chapman, 2009). By doing so, learners can see how historical knowledge is constructed and how history can be used to interrogate the roots of phenomena such as contemporary slavery.

Affective approaches to CDE

Andreotti (2006) suggests that CDE promotes the basis for caring about issues, such as those explored within this article, as matters of justice and responsibility towards the other, rather than from a belief in common humanity and responsibility for the other. Complicity in the structures underpinning, and the systems perpetuating, historical and contemporary slavery requires, from a CDE perspective, a justice-oriented approach, grounded in political or ethical principles. This affective dimension is prominent in the literature on history education. As Keogh, Ruane and Waldron (2006) argue, teaching about both contemporary and historic forms of slavery involves not just a factual understanding of what happened in the past, but also an emotive recognition of its human experience. Historical empathy and perspective taking, they maintain, can provide opportunities to connect historic slavery to contemporary issues of equality and justice. A longitudinal understanding of such concepts is central to an understanding of the relationship between historical and contemporary slavery.

A further framework of significance in the exploration of this affective dimension is the theoretical concept of historical consciousness, based on an understanding of history as a phenomenon relating to how people construct historical meaning and the ways in which they orient themselves in time (Nordgren and Johannson, 2015). Rüsen describes it as a form of sense-making where the ‘past is interpreted for the sake of understanding the present and anticipating the future’ (2012: 45). In this regard, historical consciousness can be taken as a trans-historical, trans-cultural and transnational mode of how humans relate to time, historical meaning and the world around them. Rüsen (1993) highlights the connection between the disciplinary work of HE and what he calls ‘life-practice’. Beginning with the need to orient the individual in time, he identifies the relationship between the discipline of history and the wider cultural conditions within which the discipline of history is enacted. Historical enquiries into the past begin with, and are inspired by, particular interests which are filtered through the dominant theories that learners hold about the past. Topics such as slavery are a prime example of how important an understanding of the historic roots are to positioning oneself in the present and taking action on the issue in the future.

Conclusion

This article has sought to set the context for education that engages with the issue of slavery in its various forms, with particular reference to the multiple perspectives and inherent power dynamics which frame the field. From the outset, contemporary slavery is recognised as a global development issue that is highly complex yet, in light of the severity of human suffering, demanding of an educational response. Indeed, such complexity presents a clear challenge to educators (Keogh, Ruane and Waldron, 2006), and reflection on this issue, as suggested in this article, may present many of the emotional challenges of CDE which Andreotti (2006) identifies.

There are significant allusions to the importance of a historical lens in the pursuit of CDE, and with a focus on contemporary slavery, the conceptual connections between past and present are illuminated, and the potential of HE to guide an exploration of past and present forms is recognised. The article highlighted the importance of incorporating a structural perspective in the analysis of contemporary slavery, where lines of connection and complicity are drawn between individuals, societal norms, belief systems and global power dynamics. Through the example of Ireland, the article drew these connections from the local, where structures and systems in the Irish context form the backdrop for contemporary slavery, to global issues such as land rights, displacement and climate change.

The didactic or pedagogical dimension of the proposed framework recognises the active participatory nature of CDE, but also the importance of reflection on the values which underpin understandings and decisions. Again, the potential of history education, and specifically HE, to inform this critical approach is recognised. Finally, the affective dimension of the framework is briefly considered, and historical consciousness is suggested as a framework to support historical empathy and strengthen considerations of positionality and anti-slavery action.

Comprising the fourth dimension of the proposed framework, the concept of action concerns not only the historical or potential actions of learners, but also the actions or inactions of individuals and institutions in the past and present, both against slavery and in support of the violent practices and structures that shape history and our current reality. This article has attempted to develop, through engagement with CDE and history education, the grounds for acting against contemporary slavery as a political and ethical concern, based on relationships and connections across place and time. Recognising the limitations of this project in light of Andreotti’s (2006) framework, this article is part of an ongoing process which hopes to contribute to opening up spaces that support the exploration of how DE can contribute towards a wider educational response to the injustice of slavery in all its forms.

References

Allain, J (2017) ‘Contemporary Slavery and Its Definition in Law’, in A Bunting and J Quirk (eds.) Contemporary Slavery: The Rhetoric of Global Human Rights Campaigns, Ithaca/London: Cornell University Press.

Alliance 8.7 (2017) Global Estimates of Modern Slavery, Geneva: ILO.

Andreotti, V (2006) ‘Soft versus critical global citizenship education’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 3, Autumn, pp. 40–51.

Andreotti, V D O (2011) ‘(Towards) Decoloniality and Diversality in Global Citizenship Education’, Globalisation, Societies and Education, Vol. 9, No. 3-4, pp. 381-397.

Andreotti, V D O, and Pashby, K (2013) ‘Digital democracy and global citizenship education: mutually compatible or mutually complicit?’, The Educational Forum, Vol. 77, No. 4, pp. 422-437.

Armstrong, C (2016) ‘Teaching slavery in a global context: some pedagogical themes and problems’, in C Armstrong and J Priyadarshini (eds.) Slavery: Past, Present and Future. Leiden: Brill.

Bales, K (2004) Disposable People: New Slavery in the Global Economy, 3rd edition, Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press.

Bales, K (2016) Blood and Earth: Modern Slavery, Ecocide and the Secret to Saving the World, New York: Spiegel & Grau.

Barton, K C and Levstik, L S (2004) Teaching History for the Common Good, New York/London: Routledge.

Bélanger, D (2014) ‘Labour migration and trafficking among Vietnamese migrants in Asia’, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 653, No. 1, pp. 87-106.

Blum, L (2012) High Schools, Race, and America’s Future: What Students Can Teach Us About Morality, Diversity, and Community, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Bond Development and Environment Group (DEG) (2020) ‘Addressing the Triple Emergency: Poverty, Climate Change, and Environmental Degradation’, London: Bond.

Bourn, D (ed.) (2020) The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education and Learning, London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Bourn, D (2015) ‘A Pedagogy of Development Education: Lessons for a More Critical Global Education’ in B Maguth and J Hilburn (eds.) The State of Global Education: Learning with the World and its People, New York/London: Routledge.

Bourn, D (2014) ‘The Theory and Practice of Global Learning’, Development Education Research Centre, Research Paper No.11, available: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1492723/1/DERC_ResearchPaper11-TheTheoryAndPracticeOfGlobalLearning[2].pdf (accessed 1 December 2020).

Bourn, D (2008) ‘Development Education: Towards a Re-conceptualisation’, International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 5-22.

Bryan, A (2012) ‘Band-aid Pedagogy, Celebrity Humanitarianism and Cosmopolitan Provincialism: A Critical Analysis of Global Citizenship Education’ in C Wankel and S Malleck (eds.) Ethical Models and Applications of Globalization: Cultural, socio-political and economic perspectives, Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Chuang, J (2014) ‘Exploitation creep and the unmaking of human trafficking law’, American Journal of International Law, Vol. 108, No. 4, pp. 609-649.

Cooper, H and Chapman, A (eds.) (2009) Constructing History 11-19, London: Sage.

Crane, A, LeBaron, G, Allain, J and Behbahani, L (2019) ‘Governance gaps in eradicating forced labour: From global to domestic supply chains’, Regulation & Governance, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 86-106.

Diptée, A A (2018) ‘The problem of modern-day slavery: Is critical applied history the answer?’, Slavery & Abolition, Vol. 39, No. 2, pp. 405-428.

Drinkwater, M, Rizvi, F and Edge, K (eds.) (2019) Transnational Perspectives on Democracy, Citizenship, Human Rights and Peace Education, London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Fudge, J and Strauss, K (2017) ‘Migrants, Unfree Labour, and the Legal Construction of Domestic Servitude: Migrant Domestic Workers in the United Kingdom’ in P Kotiswaran (ed.) Revisiting the Law and Governance of Trafficking, Forced Labour and Modern Slavery, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gallagher, A (2017) ‘The International Legal Definition of “Trafficking in Persons”: Scope and Application’ in P Kotiswaran, (ed.) Revisiting the Law and Governance of Trafficking, Forced Labour and Modern Slavery, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hartung, C (2017) ‘Global citizenship incorporated: Competing responsibilities in the education of global citizens’, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 16-29.

Harvey, D (2005) The New Imperialism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

International Labour Organisation (ILO) (2009) The Cost of Coercion, Geneva: ILO.

Issa, D (2017) ‘Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking in Latin America’, Latin American Perspectives, Vol. 44, No. 6, pp. 4-15.

Kara, S (2017) Modern Slavery: A Global Perspective, New York: Columbia University Press.

Keogh, D, Ruane, B and Waldron, F (2006) ‘Is Slavery History? Slavery in historic and contemporary societies’, Geographical Viewpoint, Vol. 34, pp. 7-14.

Kirby, P and Murphy, M (2007) ‘Ireland as a “Competition State”’, IPEG Papers in Global Political Economy, No. 28, pp. 3-24.

Klein, S (2017) ‘Preparing to teach a slavery past: History teachers and educators as navigators of historical distance’, Theory & Research in Social Education, Vol. 45, No. 1, pp. 75-109.

Kotiswaran, P (2019) ‘Trafficking: A Development Approach’, Current Legal Problems, Vol. 72, No. 1, pp. 375-416.

Kotiswaran, P (2014) ‘Beyond Sexual Humanitarianism: A Postcolonial Approach to Anti-Trafficking Law’, UC Irvine Law Review, Vol. 4, pp. 353-406.

Lawrence, F and McSweeney, E (2019) ‘Non-EEA migrants on Irish trawlers gain new immigration rights’, The Guardian, 22 April.

LeBaron, G (2020) Combating Modern Slavery: Why Labour Governance is Failing and What We Can Do About It, Cambridge: Polity.

LeBaron, G and Phillips, N (2019) ‘States and the Political Economy of Unfree Labour’, New Political Economy, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 1-21.

Lerche, J (2007) ‘A global alliance against forced labour? Unfree labour, neo‐liberal globalization and the International Labour Organization’, Journal of Agrarian Change, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 425-452.

Migrant Rights Centre Ireland (MRCI) (2017) Left High and Dry: The Exploitation of Migrant Workers in the Irish Fishing Industry. Dublin: MRCI.

Munck, R (2014) ‘New Paradigms for Social Transformations in Latin America’ in S McCloskey (ed.) Development Education in Policy and Practice, Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Murphy, L (2019) The New Slave Narrative: The Battle Over Representations of Contemporary Slavery, New York: Columbia University Press.

Natajaran, N, Brickell, K and Parsons, L (2020) ‘Diffuse Drivers of Modern Slavery: From Microfinance to Unfree Labour in Cambodia’, Development and Change, pp. 1-24.

Nordgren, K and Johansson, M (2015) ‘Intercultural historical learning: A conceptual framework’, Journal of Curriculum Studies, Vol. 47, pp. 1–25.

O’Connell Davidson, J (2015) Modern Slavery: The Margins of Freedom, Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Phillips, N and Sakamoto, L (2012) ‘Global Production Networks, Chronic Poverty and “Slave Labour” in Brazil’, Studies in Comparative International Development, Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 287-315.

Plant, R (2015) ‘Debate: Forced Labour, Slavery and Human Trafficking: When do definitions matter?’, Anti-Trafficking Review, Vol. 5, pp. 153-157.

Quijano, A (2000) ‘The Coloniality of Power: Eurocentrism and Latin America’, Nepantia, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 538-580.

Quirk, J (2011) The Anti-Slavery Project: From the Slave Trade to Human Trafficking, Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press.

Quirk, J (2009) Unfinished Business: A Comparative Survey of Historical and Contemporary Slavery, Paris: UNESCO.

Rezende, R and Esterci, N (2017) ‘Slavery in Today’s Brazil: Law and Public Policy’, Latin American Perspectives, Vol. 44, No. 6, pp. 77-89.

Rüsen, J (2012) ‘Tradition: A principle of historical sense-generation and its logic and effect in historical culture’, History and Theory, Vol. 51, No. 4, pp. 45-59.

Sakamoto, L (ed.) (2020) Escravidão Contemporânea, São Paolo: Editora Contexto.

Tarozzi, M and Mallon, B (2019) ‘Educating teachers towards global citizenship: A comparative study in four European countries’, London Review of Education, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 112-125.

Van den Anker, C (ed.) (2004) The Political Economy of New Slavery, Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Chris O’Connell is a Postdoctoral CAROLINE Fellow at the School of Law and Government at Dublin City University. His current research examines the relationship between climate change, vulnerability and contemporary slavery. His research has received funding from the Irish Research Council and from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 713279.

Benjamin Mallon is Assistant Professor in Geography and Citizenship Education in the School of STEM Education, Innovation & Global Studies in the Institute of Education, Dublin City University. His research focuses on pedagogical approaches which address conflict, challenge violence and support the development of peaceful societies.

Caitríona Ní Cassaithe is an Assistant Professor in History Education in the School of STEM Education, Innovation & Global Studies in the Institute of Education, Dublin City University. Her research interests include: the learning and teaching of history at primary and post-primary level, initial teacher education, museum, heritage and place-based education, digital technologies, controversial/contested issues and disciplinary literacy.

Maria Barry is Assistant Professor in the School of STEM Education, Innovation and Global Studies in DCU's IoE. She is a teacher educator and researcher in the fields of history education and global citizenship education.