Using Collective Memory Work in Development Education

Abstract: This article captures aspects of community responses to COVID-19 through a participatory and interdisciplinary approach, namely collective memory-work (CMW). Using an autoethnographic CMW, we share experiences on the theme of solidarity in the backdrop of a global health pandemic and ‘black lives matter’ across continents. As a methodology CMW has been adapted and adjusted by scholars informed by the purpose of its application, institutional frameworks, and organisational necessities.

In the summer of 2020, a CMW symposium was scheduled in an Irish university but postponed due to COVID-19 restrictions. The scholars, however, decided to go online and work on the symposium. This article provides insights into the impact of the two events on the lives of four women scholars aged between 51 and 79 years who formed one of the discussant groups. The unfolding of the two global pandemics, namely racism and COVID-19, leads to reflections upon the conflicts experienced around solidarity, especially between participating in demonstrations in solidarity with #blacklivesmatter, and distancing ourselves in solidarity with all risk groups for COVID-19. One group’s right to breathe stood in opposition to another group’s right to breathe. The process of writing this piece on CMW also taught us to collectively own our final thoughts and words in this article.

Key words: Collective Memory Work; Development Education; Solidarity; Control; Pandemic; Racism; COVID-19.

Introduction

The importance of development education (DE) in engaging critically with communities has been an area of interest in the sector of international development for over three decades. At various intervals, scholars and practitioners have stressed the need to re-invent processes of public engagement to embrace diversity and emerging challenges in social consciousness. This article addresses the above concern through insights gained from a collective memory work of four scholars across three countries in the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic and #blacklivesmatter.

Theoretically, we have framed our arguments on the emerging multifaceted nature of solidarity using the concept of alienation. Methodologically, we argue that the use of collective memory work with its aspects of timeliness, its variations, the potential fields of application, its value in teaching, learning, research, and social activism supports the building of networks for cooperation and knowledge exchange across geographical and disciplinary boundaries. More importantly, the transfer of the collective memory work into non-academic arenas sets it out as an important development education tool.

In this article, we have first explored the connections between the methods of collective memory work and development education. We then focus on the process of collectivising and discuss how we (four strangers) proceeded with the project. Starting with the common theme of ‘solidarity’ we, then, move onto emerging themes in our memory work traversing through awareness, homes and homelessness, racism, the new normal, linking the idea of ‘control’ with the concept of alienation, human agency, and learning how to focus from the act of breathing. We deliberate upon COVID-19 as an art and a portal between different worlds and conclude with the contention that CMW is a useful interdisciplinary tool to facilitate discussions and actions on emerging social tensions.

The aim is to advocate the use of memory work to bring development education into ordinary use, within control of citizens’ action. With a focus on our discussions related to agency, control, and alienation, we argue that development education facilitators could use memory work to support learners collectively to explore and still retain agency.

Understanding Collective Memory Work

Memory work is an open methodology (Haug, 2008) which offers the possibility of reinterpretation on an individual case basis and create different forms of knowledge leading to new ways of learning. Scholars such as Jansson, Wendt and Åse (2009) argue that through an analysis of reactions of participants in a collective memory work, and [new] processes initiated thereof, critical discussions emerge which help locate ruptures and ambivalences in the already known, and open-up for understandings and interpretations that takes the scholar beyond the discursively given. In the same vein, Onyx and Small (2001) contends that our construction of the self continuously influences the construction of the event, and collective memory work enables us to understand each others’ construction of a specific event and allows participant to be both the subject and the object of the constructed event. ‘Because the self is socially constructed through reflection…’ (Ibid.: 774). Thus, as Onyx and Small (Ibid.) reminds us, as a feminist social constructionist method, memory work breaks barriers between the subject and object of research collapsing the researcher with the research and making everyday experience as the basis of knowledge. Questions on relationships emerge, including those based on power. As co-researchers in a collective memory work, the participants now have the same tools at their disposal to question inequalities and relationships based on unequal power. And this is where, we argue, collective memory work, and its search for not only ‘how it really happened’ but also in its search for moments when in ‘the process of creating an image, memory becomes a tool for the dominant class’, (Haug, 2008: 538) resonates with the goal of development education.

At the core of development education is the mandate to question inequalities, injustices, and existing power structures. According to a leading development education proponent, McCloskey, development education has ‘a commitment to critical enquiry and action’. Linking it to the COVID-19 context, McCloskey further states that the DE sector ‘has an opportunity and, perhaps, a responsibility, to debate how the coronavirus crisis should be negotiated over the short and long-term’ (McCloskey, 2020: 174). In other words, DE must adopt and embrace different forms of public engagement for such a public discussion of pandemics. Collective memory workshop is one such route where learners can be trusted to design and follow their own forms of active engagement to critically reflect upon a subject of collective interest. As such, CMW ties up neatly with Oliveira and Skinner’s concern (2014) of enabling Development Education and Awareness Raising (DEAR) practitioners to conceptualise citizen engagement in a more meaningful way by taking into consideration its broad context (2014: 9 cited in McCloskey, 2016: 129).

In fact, McCloskey had earlier voiced concerns that development education had been unable to enhance citizenship engagement with international development issues through sustained action outcomes, and argued for ‘supporting learners in designing their own forms of active engagement’ with greater clarity and openness (McCloskey, 2016: 110). We contend that the role of collective memory work in engaging the public to collectively sustain action outcomes arising from such questioning and sharing of memories of inequalities and experiences must be adequately researched. This will lead to meaningful conversations amongst diverse and smaller groups of people and communities for the public good. It is this gap we aim to fill through this article.

The process: how it really happened

In the summer of 2020, a CMW symposium was scheduled to be held in an Irish university but postponed due to COVID-19 restrictions. The scholars, however, decided to go online and work on the symposium. Our host, Robert Hamm, sent out emails to all participants enquiring if we were keen to participate in an online meeting to take the symposium forward. Twenty-five of us agreed to do so. Owing to the huge numbers and, to facilitate meaningful discussions, we agreed to be divided into smaller groups depending on our time zones and availability. The first meeting was difficult for some of our participants. It was especially difficult to accommodate Australian and American participants at the same time, for example. It was either early morning hours, or late night. After the first meeting of all participants, we met three times on Zoom. Between the four of us in our group, we were an eclectic mix of women scholars between the years 51 and 79, of Swedish, Indian-Irish, Indonesian-Australian, and Australian backgrounds. Other groups had scholars from Germany, Pakistan, the Americas, Brazil, the UK, and elsewhere whom we met online for a second time at the end of the project. The starting point for this collective memory work was the concept of solidarity and how this was actualised during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In our first online group-meeting, we decided to go back to our desks between meetings to write on what emerged in our lives during the first lockdown in March 2020. We discussed how lockdowns varied in Sweden, Ireland and Australia, and how these experiences varied with ethnicity. We shared those stories through group emails. A narrative was emerging following which we decided to dig into the main conflict we experienced around solidarity, between participating in demonstrations in solidarity with #blacklivesmatter, and distancing ourselves in solidarity with all risk groups for COVID-19. There was a contradiction between our own comfort and sense of solidarity and the wider injustices based on race and class. One group’s right to breathe stands in opposition to another group’s right to breathe. As a trigger word for our memory pieces, we therefore used George Floyd’s last words: ‘I can’t breathe’ (Singh, 2020).

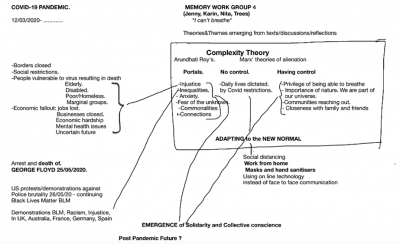

Keeping this in mind, we decided to select two memories; one a positive memory, and the other a more unpleasant one, to bring to our collective memory work. After discussing these memories through emails and Zoominars, we felt an urge to go deeper into the concept of solidarity, and in our last memory pieces we described how we encountered solidarity in our everyday life. Through a series of online meetings, learning from each other, forging a friendship based on trust and shared memories, we collectively produced this document at the end of the process. The following image (Figure 1) emerged from our memories. It provides a summary of our texts and discussion, and our conceptualisation of how these are connected.

Figure 1: Memory Work (McCormick et al., 2020)

Situating Ourselves

All four of us were aware of our backgrounds as privileged women with education mostly modelled on Western concepts. Two of us are ‘women of colour’, and two are white women. Two of us retired from paid university work, and the other two currently work in universities. Using a qualitative feminist method of Memory-Work, two of us, with others, explored (Onyx et al., 2020) a collective experience of ageing after retirement in which, following Freire (1970), we argued for a humanising pedagogy wherein ‘we’ control ‘our’ own learning, we argue for the voice of older women as agents of their own well-being, and what we found challenges the current script of ageing and social control that defines and limits who older women can be.

Similarly, we are aware of a tendency in the mainstream discourse on ‘gender and development (and/or DE)’ for example, to bring in the voice of ‘Third World women’ or women from ‘the global South’ or ‘disadvantaged people’ with ‘the implication being that Third World women speak so that ‘Western’ women-qua-‘developed’ may speak to one another about ‘them’ (Lazreg, 2002: 127). Working with Lazreg’s (Ibid.: 143) contention that the responsibility to engage with a reflexive methodology ‘which constructs itself as it constructs the subject matter’ is a task fraught with unspoken assumptions, we offer our experiences as a bridge between ‘the self’ [‘us’ reflecting as women scholars from varied backgrounds] and ‘the other’ [‘us’ again as women who are impacted by the two pandemics differently because of age and colour] by situating ourselves in the two pandemics. ‘The other’ here is our alienated self. We are women, considered ‘privileged’ and yet racialised in our everyday lives. As such we are acutely aware of the lives of the ‘disadvantaged’ sections [as it is ‘us’ also], and this is the strength of this article.

Solidarity

Our last and first question was about solidarity. What is it really? Where is it? While trying to grasp it through memory pieces, we realised that although it was fundamental to our collective work, it was something we took for granted. Without solidarity, and its accompanying aspects such as trust, empathy, love, there can be no society. Solidarity is an essential condition for humanity.

“…all stood in solidarity

each

meaningless without the other

a moment

incomplete without the other…”

Solidarity can be expressed in our daily contact with strangers as we walk through the park or just around the block. During the special circumstances of COVID-19, perhaps we smiled more, engaged in light conversation, and realised that we were together in our individual isolation. We offered kind words of comfort, small acts of kindness. We could not hug our grandchildren and friends, but we could call and text and show our concern for each other. We were unable to directly help those in intensive care at hospitals, but we as a collective adjusted to the situation, cared through small acts of solidarity, by keeping acceptable social distance as seen in public spaces when people interact carefully:

“On the subway people were sitting with distance, the informal rule seemed to be one person on every set of two pairs of chairs facing each other. The remaining people standing picked places 1-1.5 meters away from each other. She had seen no signboards or heard on social media recommending this public behavior and was amazed that everyone seemed to have figured out the same system”.

This is a quiet solidarity, largely unsung, but a very effective base for dealing with the pandemic crisis. We were separated but with a shared understanding of friendship. We also seem to be returning to a more peaceful lifestyle, while creating new ways of being part of the community. We were doing more for each other. Our sense of safety depended on ‘the other’ sharing the same urgency to be safe. In some places, community-based groups emerged to encourage people in their neighborhoods to connect with each other.

“Taara downloaded the Nextdoor app on her phone and soon received greetings and messages of welcome from people who live around her. A lady wrote ‘Say Hi when you see me walk past with my two yellow Labradors. I’d love to get to know you’. Another posted ‘Is anyone interested to go bushwalking on Sunday mornings?’ And ‘I can help do the shopping for you’. ‘I can walk your dog’. ‘My daughter is making cloth masks. She accepts orders. ‘Does anyone know a reliable gardener?’ ‘I am giving away a small fridge’, and so on”.

Neighbours invited each other to join walking groups and book clubs, offer their unwanted goods free of charge and share information about reliable trades-people and handymen. Actions such as these indicate that there is a sense of solidarity within communities. There is a willingness to regard the lives and safety of fellow human beings as equal to our own. Religious and community organisations have pulled together and offer food and support to those in need.

“This is solidarity, this is normal.

The new normal: anxiety, adaption, emergence”.

Awareness

We became aware that when COVID-19 was declared a pandemic on 12 March 2020, it not only unleashed a wave of sickness and death, but in the process exposed inequality, prejudice and discrimination experienced by minorities, indigenous people, as well as refugees and immigrants. The poor, homeless, disabled and dispossessed were also experiencing discrimination, and a greater vulnerability to COVID-19. Awareness of acute schisms in our society and environment had become apparent with the unfolding of events globally. This was reflected in our discussions and our writing.

We were also becoming more acutely aware of the contradictions between our own personal comfort and the wider fear and hardship around us. We felt, more sharply, the joys that were enhanced by our experience, especially the comforting presence of nature, and the value of our human connections with friends and family. We were walking outdoors more. We noticed the terrible injustices imposed by humans on nature. We were having evening tea everyday with overseas siblings and parents over WhatsApp. Suddenly we had more time to complete tasks we had postponed. At the same time, we also felt more sharply our own anxieties, the social distancing that alienated us from friends and family at an immediate level, and the terrible injustices made visible. We began to question the solidarity we wanted to feel. There was a contradiction in articulating ‘we are all in this together’, except that we were not in it together!

This awareness which existed within us in a latent form manifests in our collective memory work because we as society were forced by the lockdowns to pause and reflect on our lives. Participating in the workshop allowed us to express our deepest thoughts on the two pandemics of 2020, to dwell on the possibilities of becoming overwhelmed or to be able to overcome the crises, to reach out to others, and to collectively deal with the enormity of the problem we faced as a global society. As such, CMW has enormous potential as a tool for development education practitioners in communities facing similar difficulties in dealing with other crises. Older hitherto hidden patterns of structural inequalities between groups, classes, communities, and continents emerge and can be collectively challenged without leaving anyone behind.

We, therefore, argue that through our collective memory work on the experience of solidarity during periods of social crises we provide key lessons to development education in different contexts.

“Key in the analysis of remembered history are contradictions. In turn, these are a methodological tool that must permeate and complicate the linear search for truth ‘as it actually happened’. The result of such Memory Work is thus not rectifying or establishing the correct image; neither is it advice on how to get to the correct perspective or how far removed one is from it. Perhaps it is more than anything restless people with new questions, who are in a process with the intention of moving themselves out of a position of subalternity” (Haug, 2008: 538).

Central to collective memory work has been the presence of contradictions or different truths from different perspectives of all participating agents in the process. All truths have equal weight in the final analysis. Emerging features of trust, empathy, kindness, neighborhoods, collectiveness, bridging the self with the other through ‘social distancing’ amongst others have vast potential as transformatory tools which development education needs to equip itself with.

Racism

Racism was laid bare by COVID-19. In one memory when shopping for toilet paper, the author becomes acutely aware of a perception, a stereotype of a Chinese hoarding toilet paper. The racism is subtle, and maybe only in the author’s imagination, but still very real and present. It affects us all. Subtle moments of discomfort in public spaces needed to be called out. We were four women of different ethnicities and of different ages, and experienced racist discrimination differently.

“As Taara rounded the corner where tissues and toilet paper were kept, she spotted one lonely packet of toilet paper on the top of three rows of empty shelves. As she put the last of the six packets in her trolley, Taara noticed that a few customers turned their heads and watched her. She was aware of a video that had gone viral on social media of an Asian man running in and out of a supermarket buying toilet paper. She also heard in the news on television that people from Chinese descent have been abused and harassed during this time. Taara felt her heart thumping away and willed herself to breathe calmly as she stared straight ahead and walked with ‘unseeing eyes’ to the checkout”.

COVID-19 fear reveals racism in unexpected spaces. Racism is quite banal sometimes especially when it is about fear of the un-known. People who do not mirror you become a threat. The crisis revealed our deepest fears and long forgotten biases. Our discussions revealed that this basic fear of what doesn’t look familiar, later, reproduces structural discrimination embedded in the foundation of our societies.

Homes and Homelessness

In this case, the problem of homelessness stared at us. Home quarantine requires a home! At the peak of the pandemic, the city centers were desolate, and those who remained out on the streets were those who had nowhere else to go. Those who were usually in the periphery, hidden away in the darkness of the night, suddenly were a majority in the city's outdoor spaces. The homeless claimed our streets. A second realisation dawned that we, the authors of this text, all have homes! We had options earlier, to go out to work and come back home in the evening. We faced a new challenge - now our homes have also become our offices.

“Stuck in our homes we have begun to rely much more on online communication, and tools like Zoom in combination with the pandemic sometimes creates an unexpected intimacy. You stare at these tiny moving portraits of people in their home environment, and phrases such as ‘how are you’’ or ‘hope you are well’ aren’t empty phrases any more. Everyone is happy to share all the details of their sore throat”.

One of the first things I thought when I heard of a lockdown was:

“Oh gosh! This means all 4 of us will be in the house 24/7

…This was going to be the end of us”.

This intimacy, sharing personal environments and bodily sensations, also points out the differences. When meeting outside neutral offices, we encounter personal home environments, filled with strange colors, sounds and animals. We became aware of the differences in our group, geographically, historically, socially. Even if we believe this virus unites us, it also reveals the differences in our realities, differences that were not obvious at international conferences and meetings. Earlier our designations and roles represented us in meetings, not what we had in the backdrop of our screens in the living room or study. And then how many of us in a family can share a study while at work? These were unique issues which led us to think of the importance of collective memory work, and therefore as a tool for development education, to reflect on shared spaces in communities without hesitation. We worked on this piece together from kitchens, living rooms, attics, and cars.

Fear, anxiety and risk

One of the important findings of our collective memory work was the recognition of a fear, an anxiety, and possible risks in stepping out of homes, or connecting with people outside our homes. As we share the experience of the pandemic with others in our society, it does not automatically lead to solidarity. Many of us hid indoors (if we have a home), and focused on our individual health and happiness, facing the risk and anxiety of our own death in isolation. The recognition and acceptance of such an anxiety was not possible without collectively writing and sharing our memories of the pandemic. And hence, we strongly advocate its use as a development education tool to be used in contexts where the aim is to delve deeper into people’s psyche to understand what holds them back, and what, for example, perpetuates conflicts. It has the potential to bring people together through a collective dialogue to reflect upon the others’ actions which may be perceived as taking risk or avoiding a risk in a situation of sudden change.

Interestingly, the words ‘fear’, ‘anxiety’ and ‘stress’ did not appear in any of our written memories. Nevertheless, the emotion that these words convey were woven throughout our writings as we described what we did, saw, heard, smelled and felt. Reading through our memories, one can feel the sense of unease, of not being completely comfortable, of being on edge. It was a feeling of uneasiness, nervousness and anxiety in all of us. A perplexity about how this pandemic had suddenly changed our daily lives! Our worlds had changed, and we were unsure about how to handle the new normal. We did our best to adapt to our new circumstances by making new routines to normalise what was clearly abnormal to us. We now keep hand sanitisers in our handbags, wear masks, maintain social distance of 1.5 meters from our friends, and refrain from visiting crowded places. We participate in meetings and concerts online instead of attending in person. We cancel dinner parties, holidays etc. It is a bit like the first scene in a horror movie, where subtle details reveal that not everything is alright and what follows has the possibility of becoming the unexpected and terrifying. A slow realisation dawns upon us that one is never in total control, and that a situation we take for granted can change quickly.

Losing control versus alienation

A theme that emerged in our memory work was the contradiction in the texts between situations of control, such as being a determined individual in one’s own context acting in the world, and with situations without control, especially of being stereotyped, de-individualised and having to submit to a larger system upon which we have no influence. This paradox of being in control and yet not having control in many other ways, corresponds to a kind of ‘alienation’ discussed by Hegel and Marx (see Byron, 2013 and Sayers, 2011 for a detailed discussion on Hegel and Marx’s concept of alienation). According to Marx, in a capitalist economy, individuals become alienated from their product of labour, the labour process, others around them, and from their selves. For Hegel, alienation was more of an estrangement of the spirit in the life of a human. Elsewhere, taking cue from Hegel, Sayers argues that all human phenomena follow a path beginning with ‘an initial condition of immediacy and simple unity’ to ‘a stage of division and alienation’ culminating ‘in a higher form of unity, a mediated and concrete unity which includes difference within it’ (Sayer, 2011: 289).

Our emerging theme shows a similar process arising during COVID-19 where we hope humanity reaches a stage of ‘adult maturity and self-acceptance’ (Ibid.). Additionally, for this project of healing, maturity and acceptance of contradictions and conflicts within society, a step forward would be to blend Aristotle’s concept of good and happiness with Marx’s theory of alienation as contended by Byron. Byron argues that ‘it is normatively satisfactory to restructure the forces that give rise to alienation’ (2013: 434). Thus, our contention that the concept of alienation is useful to understand people’s conflict with their selves and with others while at the same time expressing solidarity, in the COVID-19 context holds ground. We further include arguments made by Raekstad:

“Marx's theory of alienation is of great importance to contemporary political developments, due both to the re-emergence of anti-capitalist struggle in Zapatismo, 21st Century Socialism, and the New Democracy Movement, and to the fact that the most important theorists of these movements single out Marx's theory of alienation as critical to their concerns” (2015: 300).

Having human control over our own conditions enables expressing oneself, leading to self-realisation, and being in direct relation with oneself and others. The opposite of this relational individual, is an interchangeable pre-programmed and un-creative person, alienated from itself and its fellow human beings, alienated in relation to its living conditions, at best a cog in the machinery. An example of losing control over your own narrative, being stereotyped and therefore de-individualised is in the memory of buying toilet paper (above), where the main character experiences a notion of racial profiling, suddenly fearing people categorising and labelling her as ‘Asian’ in a white-man’s country. ‘Without control: stereotyped, de-individualized, out of breath.

Losing control over one’s life was apparent in another memory piece. We found another example of losing control, becoming de-individualised, and categorised, as old (over 70 years), and therefore treated as potentially sick and in need of care (rather than being an actor with multiple capabilities).

“Then news of a planned demonstration in Sydney. It was lockdown. People, especially those over 70, like Jo, were told not to leave the house. It was too dangerous. The authorities tried to ban the proposed (anti-racism) demonstration for health reasons”.

Without much thought, we realised, that certain groups of people were ‘advised’ to stay indoors while others could step out. The intentions behind such policies were driven by a notion of public good which was perhaps not based on evidence from the public (the over 70’s age group in this case) it tried to protect. Ultimately, this is what COVID-19 was doing. We lose control, we can’t breathe without assistance, we are no longer in charge:

“Jo remembered a documentary on COVID-19 and how it causes death. Apparently, in the final stages, it affects the lungs, which is why there was a desperate call for ventilators for hospital intensive care units. The person may still breathe, but the carbon dioxide is no longer expelled, oxygen no longer absorbed. Basically, the person suffocates”.

Without being able to control our breathing we will ultimately die, figuratively as well as literally.

“Couldn’t breathe

Barely out of the emergency

Out of the ambulance...”

In sharing these memories, we want to argue that in situations of losing control or having no control over one’s life conditions, as communities living in poverty will give testimony to, using the tool of memory work collectively will throw a beacon of light on different dimensions of poverty and inequalities.

Having control and human agency

In contrast to losing control and becoming alienated, our memory work also elicited examples of having control. These memories were about being in nature, meditating, yoga, and participating in public demonstrations in solidarity with ‘the other’. Our memory about nature is a beautiful example of being an individual in a certain context, about being special, situated, with a history and belonging, very much alive and breathing:

“She picked a twig lying on the ground and breathed in the familiar fragrance of the most iconic Australian tree. It’s a smell that directly transports her to this park, to Australia, to home”.

In another piece on meditation, the main character becomes aware of her special breath, and announces that being her, being human, is also about being in control. To control breathing is to be empowered, aware and therefore in control while also embracing what is outside our control, which becomes a way of controlling one’s reactions towards the unknown.

“But gradually Jo became aware that this breath was rather special. In fact, it was life. Without breath, she would be dead. Breath is simply taken for granted, that is until it stops. We all breathe constantly, usually without effort, without thought. To focus on breath, to really focus, is to fully appreciate the sanctity of life”.

Similar in this memory piece where yoga is about taking action, regaining control-

“Yoga

It is time to re-start

… So, I started yoga

Slowly but surely…”

The memory-piece describing public demonstrations in solidarity with #blacklivesmatter was also very much about being able to take action, regain control, and to assert the right to breathe.

“But ordinary citizens around the world had had enough of these deaths of unarmed black people. The demonstration was going ahead regardless of its legality. Black lives matter. They have the right to breathe. We as citizens must stand in solidarity with them”.

Thus, as we note from the above examples, in memory-work, agency of participants is central to the method where participants:

“…spin the web of themselves and find themselves in the act of that spinning, in the process of making sense out of the cultural threads through which lives are made…” (Davies, 1994: 83 cited in Onyx and Small, 2001: 782).

The crisis revealed the presence of conflicting rights within society. To emphasise one’s right to express oneself or to follow the authority’s recommendation to ensure others’ rights to breathe. The crisis also showed that we can take control. Either we fall victims of the pandemic within ourselves, and outside ourselves, or we use it as an opportunity to rise above the pandemic to reveal our higher selves, to take responsibility, collectively and socially. One memory piece noted:

“Wondering how ordinary patients cope [in the red zone of government hospitals]

She [COVID-19 patient, lawyer sister] sent in a written complaint to the courts

Evidence-based proof of mismanagement

Unhygienic, water starved toilets

Helplessness of patients

Walled in the red zone…”

Thus, our memory work reflects upon ordinary lives taking cognisance of a (utopian) society where one is active and creative within existing life (threatening) conditions alongside others. As such, it holds immense potential for development education as a means to rise above our immediate conditions. For this notion of control should not be mistaken for selfish individual freedoms which leads to alienation from relations but as being connected and responsible for each other. Similar to breathing in meditation, as noted in our work, where equal ‘focus’ to all thoughts crossing our mind to create a higher awareness is encouraged, the two pandemics become tools to reflect on society in a different light, perhaps with all its faults and strengths. In this sense ‘the COVID-19 crisis’ is a bit like art, as it frames and highlights what is important. At best it makes us acutely aware of something that we mostly ignore as being banal, or so obvious that we can’t see it without help.

“Prana, my breath called me out

…To understand the breath

The very essence of life

‘prana’ my breath…”

The new normal

The writing process brought acceptance of the ‘new normal’ albeit marked by anxiety, for us. The term was like a mantra to convince ourselves that we are perhaps coping or should be coping. There is a kind of feeling that ‘this is the new reality and it’s not going away…so get over it’. Public dialogue increasingly begins to focus on mental health of all people, and not only of those who could afford paid services. Suddenly well-being became a household word. It was about our coping or not being able to cope with the pandemics, and not just about some ‘other’ in a faraway global South context.

The ‘new normal’ aptly illustrates the process of our own memory work. We describe our own pain, the loss of routine, the anxiety, and the threat of the unknown. We then reflect on our experience, search for, find and deliberate upon deeper meaning. Some of this reflection leads to a heightened awareness of the injustices in our societies.

“calling, cajoling, coaxing all she knew in high-places

…Courts set up an investigation committee

matters set in motion by

a COVID-19 survivor”.

A reflection

We are in the process of engaging in the production of knowledge [about development], and instead of ‘collecting witness accounts about development’ (Lazreg, 2002: 127), we offer to be the subject as well as the object. This is in itself a powerful tool, facilitated by CMW, which we argue could be used in DE to roll out the ‘transformatory changes’ it purports to. Borrowing from Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970), we contend that to be transformatory, we must go beyond conventional models of pedagogy, in favour of a more humanising pedagogy that challenges the status quo between the learner and the teacher, and between the oppressed and oppressor. As co-producers of knowledge we have shown that the production of knowledge is a combination of serious reflection and action between equals, a horizontal dialogue guided by love, humility, faith and mutual trust.

Some of our deliberations lead us to a new mindfulness of our own good fortune, of the healing properties of nature, of the sanctity of life-giving breath. We are left with many unresolved questions: how to redefine friendships, how to heal nature, how to support each other, how to earn a living, how to restore social justice, for example. There is a sharper awareness. Rather than tracing a linear process of causality, we seek to identify myriad decision-making moments of individuals, communities, and the institutions. Situations are constantly emerging out of this interaction as a co-creation of people and external conditions. This process has no finite ending. It can lead to destructive outcomes, but also to personal growth and new societal patterns to support greater fairness. Through a process of disruption, anxiety, reflection, of finding new positives and adopting new practices, the ‘new normal’ offers itself as a tool or method to development education processes. The ‘new normal’ has the potential to facilitate the interrogation of layered memories of participants because:

“Many of these layered stories can be seen as evidence of the everydayness of crisis, and of the frightening power of ‘the general training in the normality of heteronomy’ — the normality of external control, of other people’s rules” (Johnston, 2001: 36 cited in Onyx, 2001: 781).

Understanding this ‘new normal’ becomes easier through the tool of collective memory writing process which captures an essential aspect of development education where educators are fumbling for newer and more effective methods of documenting and analysing societal anxiety. This can be observed below:

“Momentum and movements for change are quietly (and sometimes loudly) occurring, across the many spaces and places where justice remains denied. If you care to look and listen, you will see and hear them. Looking beyond the fatigue of the 24-news cycle and a hardening indifference to images of suffering, you will see these moments in the volunteer search and rescue White Helmet workers in Syria, the Fairtrade towns and school committees, the divestment in fossil fuels campaigns, the indigenous communities and women’s rights groups challenging traditional land and inheritance laws and customs in places like Kenya and India and in the onward journey of the human rights movement worldwide” (Daly, Regan and Regan, 2016: 9).

Furthermore, the use of new means of online communication to bridge distances mixes our private and public self which sometimes creates awkward situations, where the private domain is juxtaposed by one’s public role creating an awareness of the subtle but strict borders between different social worlds. In an interview, Arundhati Roy suggested that we should look at COVID-19 as ‘a portal between different worlds’. Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew (Roy, 2020).

The idea of COVID-19 as a portal between worlds is a useful image which directs attention to the potential of the crisis to bring us together, de-alienating us by making us lose control over our petty lives and facilitating opportunities where we are interested in finding alternative sustainable means of ‘control’ than reproducing existing unequal social lives. As such, this portal summarises some of our discussions on how the pandemic reveals inequalities (between different worlds) but also commonalities and connections (portals). This learning through our collective memory work, brings focus to the importance of all voices as all are affected by the pandemic, though differently, while agreeing that the method is ideal for extending the findings to other voices. The contrast of the two pandemics for us ‘privileged’ authors represented important learning for us, as growing awareness of the injustice of black lives matters.

References

Byron, C (2013) ‘The Normative Force behind Marx's Theory of Alienation’, Critique: Journal of Socialist Theory, Vol. 41, No 3, pp. 427-435.

Daly, T, Regan, C and Regan, C (2016) 80:20 Development in an Unequal World, 7th Edition, Oxford: New Internationalist.

Davies, B (1994) Poststructuralist Theory and Classroom Practice, Geelong, Victoria, Australia: Deakin University Press.

Freire, P (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York, Continuum.

Haug, F (2008) ‘Memory Work’, Australian Feminist Studies, Vol. 23, No. 58, December, pp. 537-541.

Jansson, M, Wendt, M and Åse, C (2009) ‘Teaching Political Science through Memory Work’, Journal of Political Science Education, July, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 179-197.

Johnston, B (2001) ‘Memory-work: The power of the mundane’ in J Small and J Onyx (eds.), Memory-work: A Critique (Working Paper Series, 20/01), School of Management, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia.

Lazreg, M (2002) ‘Development: Feminist Theory’s Cul-de-sac’ in K Saunders (ed.) Feminist Post-Development Thought, London: Zed Books, pp. 123-145.

McCloskey, S (2020) ‘COVID-19 has Exposed Neoliberal-Driven “Development”: How can Development Education Respond?’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 30, Spring, pp. 174 - 185.

McCloskey, S (2016) ‘Are we Changing the World? Development Education, Activism and Social Change’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 22, Spring, pp. 110-130.

McCormick, T, Onyx, J, Hansson, K and Mishra, N (2020) ‘Memory Work Group 4’, Collective Memory Writing Symposium, Summer, Online Meetings.

Oliveira, S and Skinner, A (2014) ‘Journeys to Citizen Engagement: Action Research with Development Education Practitioners in Portugal, Cyprus and Greece’, Brussels: DEEEP, available: http://deeep.org/wp content/uploads/2014/05/DEEEP4_QualityImpact_Report_2013_web.pdf (accessed 24 April 2015).

Onyx, J and Small, J (2001) ‘Memory-Work: The Method’, Qualitative Inquiry, Vol. 7, No. 6, pp. 773-786.

Onyx, J, Wexler, C, McCormick, T, Nicholson, D, and Supit, T (2020) ‘Agents of Their Own Well-Being:Older Women and Memory-Work’, Other Education: The Journal of Educational Alternatives, Vol. 9, Issue 1, pp. 136-157.

Raekstad, P (2015) ‘Human development and alienation in the thought of Karl Marx’, European Journal of Political Theory, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 300–323.

Roy, A (2020) ‘The Pandemic is a Portal’, Financial Times, 3 April.

Sayers, S (2011) ‘Alienation as a critical concept’, International Critical Thought, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 287-304.

Singh, M (2020) ‘George Floyd told officers “I can't breathe” more than 20 times, transcripts show’, The Guardian, 9 July, available: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jul/08/george-floyd-police-killing-transcript-i-cant-breathe (accessed 1 February 1 2021).

Note:

We are indebted to Karin Hansson for her inputs and comments on this paper. Karin is one of the participants and co-author of the original draft product. Dr Hansson is currently Associate Professor in Computer and Systems Science at Stockholm University.

Nita Mishra is a reflective development researcher and practitioner, and occasional lecturer in International Development. She is currently engaged as a researcher on a Coalesce project focusing on social inclusion of rural to urban migrants in Hanoi, Vietnam at University College Cork. Her research focuses on women and human rights-based approaches to development, feminist methodologies, environment, migrant lives, community-based organisations and peace studies. Nita has extensive experience of working at grassroots level with civil society organisations, faith-based organisations, and funding bodies in India. She is the current Chair of Development Studies Association Ireland, Director on the Board of Children’s Rights Alliance, national coordinator of Academics Stand Against Poverty-Irish Network, and member of other community-based organisations such as the Dundrum Climate Vigil. Email- nita.mishra@ucc.ie

Jenny Onyx is Emeritus Professor, Business School, University Technology Sydney, Australia. She has over 100 refereed publications across fields of community management, community development and social capital, response to inequalities by age, gender, ethnicity, disability, and collective memory work. Email: Jennifer.onyx@UTS.edu.au.

Trees McCormick is a retired teacher/educator living in Sydney, Australia. She holds a B.Ed from Indonesia and a M.Ed from University of Sydney. Trees has taught in schools, universities and institutes of technology in Hong Kong, China and Australia. Prior to retirement she worked for TAFE NSW Northern Sydney Institute of Technology. Email: treesmcc@gmail.com.