The Wrong Tool for the Job? The Application of Result-Based Approaches in Development Education Learning

The Policy Environment for Development Education

Abstract: Results-based approaches (RBAs) to evaluation have become central in development cooperation and were applied to development education (DE) evaluation in 2012 by Irish Aid, the primary funder of DE work in Ireland. After almost a decade of using results-based approaches in DE, it is timely to review their use as a measurement and evaluation tool, recognising the evidence provided as valuable, as well as naming many issues of concern over their continued application. While the use of results-based approaches is compulsory for all Irish Aid funded DE work in order to align with Irish Aid’s strategic goals, there has been some flexibility in their application. We highlight some innovative practices in measurement of results used by the DE sector in Ireland in this article.

RBAs can be effective at tracking change at institutional or programme level; additionally, this approach can bring a strategic goal-orientated outlook to organisational planning. But overall, we argue that RBAs are not appropriate tools for measuring development education learning. Many negatives are highlighted: the results chain view of learning as linear; the assumption that DE can be measured separately from other life events or actors; the failure to take into account the varying capacity of DE practitioners; and the tendency of the format to encourage ‘soft’ DE learning outcomes. We suggest that the use of RBAs encourages less radical and transformative DE ‘results’ and misses attitudinal and value changes, as well as the vibrancy, innovation and enthusiasm of the DE sector in Ireland. The richness of DE learning and its effects on participants is lost, especially in assessing the full range of pedagogical effect and learning in the attitudinal and affective domains. To paraphrase Chambers (1997), DE ‘results’ become reduced, controlled and simplified.

Key words: Development Education; Learning; Evaluation; Results-Based Approaches; Critical analysis.

Introduction

During the past decade, the monitoring and evaluation environment for development education (DE) in Ireland has been increasingly dominated by the use of results-based approaches (RBAs) to measure their effectiveness. In this article, we review the implementation and use of RBAs in DE work in Ireland; we recall their initial application by the primary source of DE funds in Ireland, highlight some of the innovative strategies employed by DE practitioners to measure and evaluate their work, summarise the primary issues with the use of RBAs in education, and conclude by reflecting on future directions for the monitoring and evaluation of DE work. RBAs are well embedded into all current Irish Aid-funded DE project funding and play a central role in how all grantees report DE ‘results’. It is timely to review the events of the past eight years showing how DE practitioners in Ireland have adapted to the imposing of RBAs onto their work. We highlight some examples of where Irish DE organisations and practitioners have adapted to use of RBAs in an innovative manner, but questions and challenges remain about the adoption of this approach to the measurement of DE learning.

What are results-based approaches?

RBAs originated in the international development sector and can be described as a management strategy that focuses on the achievement of measurable results and demonstrating impact. Throughout the 2000s, OECD (organisation for economic co-operation and development) countries agreed to use results-based management strategies to improve aid effectiveness and monitor results. Results-based management (RBM) is defined in development cooperation by the OECD/ Development Assistance Committee (DAC) as a ‘management strategy focusing on performance and achievement of outputs, outcomes and impact’ (OECD, 2002). This approach measures if policies and programmes are effectively and efficiently producing the expected results, where improving performance is the central orientation and accountability is its secondary function.

RBAs are most commonly represented in a ‘Results Framework’, which articulates the result/change that is sought in the target group, details key indicators that demonstrate the desired change is taking place, and displays baseline and target data in order to chart progress towards the programme goal. RBAs are often visualised through a results chain, a linear chain where inputs and activities lead to outputs, outcomes and impact. While it has been applied in aid and international development, the origins of the approach lie in management theory for the corporate world and public administration (Vähämäki, Schmidt and Molander, 2011). These strategies reflect the reforms in public administration termed New Public Management, which emphasises proof, effectiveness, efficiency and accountability (UN Secretariat, 2006). Designed to improve the public sector and government performance, they bring the focus of public spending and policies onto results and outcomes, rather than process or procedures. The reform movement aims to essentially apply entrepreneurship, competition, and market-based mechanisms to public policy.

This reform impact can be seen in how education has become market-led rather than a public service; the emphasis is placed on performance and ranking measured by evaluation outcomes such as grades and graduate employability in a system of increased surveillance and seemingly open choice (Lynch, Grummell and Devine, 2012). New managerialism undermines education as public right and the ‘purpose of education is increasingly limited to developing the neo-liberal citizen, the competitive economic actor and cosmopolitan worker built around a calculating, entrepreneurial and detached self’ (Lynch, 2014: n.p.). Whilst the impact of new managerialism is seen in recruitment and educational administration, it also influences pedagogy where output is emphasised over process. Teaching becomes an efficient exercise of data input and instruction, where student passivity is encouraged rather than participation, reminiscent of Freire’s concept of education as banking (Freire, 1970). The knowledge that is valued is what the ‘entrepreneurial and actuarial self’ requires for market performance (Lynch et al., 2012: 22). A culture of carelessness is created diminishing the pastoral aspects to teaching and where moral values such as solidarity and care are diminished (Lynch, 2014) - arguably the global orientated values that DE promotes (Bourn, 2014).

Imposition of results-based approaches in Ireland

The shift to RBAs in Ireland was driven primarily by Irish Aid (IA), the major funder for DE in Ireland. Having successfully embedded RBAs across their international development cooperation work, Irish Aid sought to extend this approach to their DE work. In conjunction with the publication of their new DE strategy in 2016, Irish Aid published their Performance Management Framework (PMF) for DE covering the period 2017-2023 (Irish Aid, 2017). The PMF links DE work to Irish Aid’s broader strategic goals. This goal for DE states:

“People in Ireland are empowered to analyse and challenge the root causes and consequences of global hunger, poverty, injustice and climate change; inspiring and enabling them to become active global citizens in the creation of a fairer and more sustainable future for all through the provision of quality development education” (Irish Aid, 2017: 4).

This overall strategic goal is broad enough to include all DE sectors, formal and non-formal education as well as youth and community work. It is also broad enough to encompass a wide range of DE topics and projects. Arguably, it asks for critical DE addressing the root causes of poverty and injustice (Andreotti, 2006), although the critical and political nature of addressing these causes may conflict or find culpability with government policy.

Since 2012, all DE projects and programmes funded by Irish Aid have been obliged to include a results framework in funding applications and in end-of-project reports. From 2017 onwards, these reporting requirements have included particular forms of data on DE work. Some disaggregated data on participants in DE programmes is also requested in these reports; disaggregated by gender, age, sector, educational level (e.g. early childhood education, primary, post-primary), third level by discipline, and non-formal education. Specific questions for inclusion in all post course surveys/ evaluations are given to grantees, and learners’ answers are to be reported to Irish Aid.

The grantees’ results framework is not expected to mirror the Irish Aid performance management framework document, rather flexibility is encouraged and grantees were tasked with writing their own indicators and outcomes, where outcomes are defined as ‘changes in skills or abilities that result from the completion of activities within a development education intervention’ (Irish Aid, 2017: 3). Whilst flexibility exists in the writing of a grantees’ results framework, nevertheless it must be stressed that all funded DE projects are required to contribute to the outcome indicators of Irish Aid’s PMF for 2017- 2023. Furthermore, the DE project performance indicators of the project must be in alignment with the language of the Irish Aid PMF (Irish Aid, 2019: 12). This is a requirement for funded projects.

The adoption of RBAs in the evaluation of DE was not a decision of the DE sector in Ireland; the use of these approaches was imposed as an essential element to the funding granted. This imposition from above was initially met with resistance from development education practitioners, who questioned the appropriateness of using RFs in educational contexts (Gallwey, 2013). However, the Irish Development Education Association (IDEA), the national Irish network of development education organisations and individuals, has facilitated constructive dialogue between Irish Aid and the DE sector. The DE sector has accepted the need for DE to deliver measurable results in terms of Irish Aid’s strategy. DE practitioners also have recognised that a focus on results can lead to valuable critical reflection about what we do, why we do it, and how we can improve our practice. Indeed, anecdotal evidence suggests that RBAs are effective in measuring impact at institutional or programme level, for example, tracking the extent to which DE has been integrated into Initial Teacher Education (ITE) courses, or tracking progressive stages of engagement by schools enrolled in a global learning programme. Like a Theory of Change, a RBA compels organisations to examine how change happens in their area of work, and thus enables refinement of inputs to better meet the needs of target groups.

Irish Aid’s willingness to be flexible has allowed for some innovation and contextualisation of results frameworks to specific DE settings. For their part, Irish Aid acknowledge the value of qualitative measures of learning and accept that there are difficulties inherent in capturing the complex, long-term attitudinal changes characteristic of DE. This is a primary concern with the use of RBAs as measures of learning in education and is described in the next section.

Results based approaches in education: the ‘proof’

There are a number of positives in the use of RBAs for DE. The primary positive feature is that the data gathered provides evidence of the vibrancy and range of work carried out by DE practitioners and organisations in Ireland. This evidence is necessary for accountability of how public funds are utilised effectively and to support the continuation of DE work by making a case for further resourcing and funding. Additionally, the presentation of DE ‘results’ in a format similar to other Irish Aid work helps to secure the position of DE within the overall IA programme.

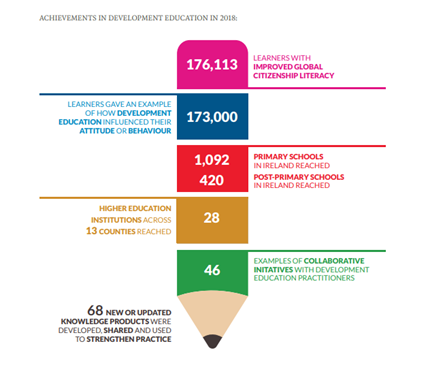

In their annual report for 2018, the data collected from the Irish Aid DE annual reports, DE Strategic Partnership Programme, and Programme Grant funding streams is shown in the following infographic:

Figure 1. ‘Achievements in DE in 2018’ (Irish Aid, 2019: 54).

The collective data was shared with the IDEA Quality and Impact Working Group for review on its usability and informativeness. This raw data highlighted the vibrancy of the sector and the range of work carried out, the high volume of participants and learners, and the geographical spread across the island. In the ensuing discussion, the Working Group raised issues of concern, such as General Data Protection Regulation (GPDR) challenges in reporting learners’ characteristics. While presenting interesting data, there were large gaps missed in this infographic, which seems to flatten the energy and enthusiasm of the DE sector. The range of activities across formal and non-formal education is absent. Feedback from learners or measures of their gain from DE (beyond stated changes in their behaviour or attitudes) are absent. However, we recognise that this infographic is the beginning of the reporting on DE ‘results’ by Irish Aid and hopefully more depth of data will be visualised and included in future reports.

Difficulties with use of RBAs in development education

This section outlines the many negatives on the use of RBAs; firstly, they are clumsy instruments, focused on counting and numerical scores of results which work towards an overall impact, rather than rich accounts of learning on development, the range of topics addressed, and activism for positive social change. The inherent assumption as illustrated in a results chain is a move by learners in a positive, left to right spectrum, as a learner will move from ‘little or no’ knowledge to more. But this assumes that gaining knowledge is positive while the reality is that more knowledge may lead to more questions, confusion in their values, or indeed lead to rejection of knowledge as it may challenge biases and assumptions about how the world works (Allum et al, 2015). Also designing a pedagogical intervention based on objective development knowledge is straightforward, drawing on development studies and political economy knowledge. However, addressing the subjective responses to global learning is more complex as many factors mediate the affective learning domain including beliefs and morals, efficacy and emotional responses (Liddy, 2020). How are these elements of learning to be measured and counted? Can we measure a transformation? Or more profoundly, should we even attempt to quantify a learner’s values, emotions and beliefs? DE should aim to create a pedagogical space for questioning and challenging values and beliefs, even allowing for unknown beliefs and attitudes to emerge during learning activities rather than aiming to measure, quantify and attribute changes.

The influential role of the DE practitioner is an important factor when attempting to evaluate DE resource material. In a study on the use of the Just Children resource for young children (Oberman, 2010), Judith Dunkerly-Bean and colleagues (2017) found that learners’ understanding of poverty and inequality depended on the ‘nexus of practice’ established by their teacher. For example, one teacher in Dunkerly-Bean’s study unconsciously framed poverty as ‘a choice that those who are resilient can potentially overcome’, thereby creating a value-laden framework through which her pupils made meaning from the Just Children resource. Therefore, if we are attempting to assess the impact of a resource, we have to ask: are we assessing the impact of the resource as it was produced, or are we assessing the impact of the resource as it is delivered within the nexus of practice of an individual educator? Where are the values and attitudes, even the knowledge of the educator addressed and measured? Are the root causes of poverty and injustice named and challenged, or is poverty framed as a personal choice? The information the practitioner gives in their work, as well as their values and ideological assumptions on the topic must be interrogated, or else it can run the risk of ‘indirectly and unintentionally reproducing the systems of belief and practices that harm those they want to support’, as Andreotti (2006: 49) argues. This interrogation becomes more necessary in an era of new managerialism with the dominance of economic imperatives over global justice values.

A key element in DE is action; the definition of development education by Irish Aid (2006: 9) says it ‘seeks to engage people in analysis, reflection and action for local and global citizenship and participation’. However, actions arising from a DE programme could have a wide variety of results; for example, learning on food miles may encourage one learner to be a more local based consumer while another learner could argue to support farmers in developing world contexts through buying imported fruit and vegetables. Can these two results be reported in a similar manner in a pre-defined results framework? And if we merely count actions arising, then do we encourage questionable activism such as charity and fundraising?

The temporal dimension is a further issue; the results chain is read from left to right following the timeline of the funded project. Many of the projects funded by Irish Aid in recent years have been funded on an annual basis as opposed to the three-year funding offered in the past (the reinstatement of two-year grants in 2019 was a welcome step in the right direction). This short timeframe has two implications. First of all, what ‘results’ can be expected after a year? Secondly, most of the DE project work lacks a continuity of learners. Only in formal education can you assume a long-term engagement (i.e. post-primary 5-6 years; third level 2-3 years). Furthermore, many DE programmes target a specific year group (often Transition Year) and thus have a new cohort of students every year. Without this continuity, opportunities for gathering baseline data and tracking DE learners over a period of time is gone.

A further issue is the inherent challenge of attribution versus contribution in evaluation of education interventions. For example, if we are carrying out a DE programme on diversity, using learners’ pre- and post-programme work to track how attitudes towards diversity changed, how can we be sure that any changes we observe are a result of the DE programme? And can we even draw a boundary around a ‘DE programme’? In reality, learners are exposed to a myriad of influences outside of the DE setting, including family, community, and the media. Inside a classroom or non-formal setting, a DE initiative does not operate in a vacuum either but is integrated into the educator’s overall practices. Recently, Trócaire and Centre for Human Rights and Global Citizenship applied a pre- and post-programme approach to research on the impact of the Just Children resource for early childhood settings (Gallwey and Mallon, 2019). This included a photo-based activity in which children discussed similarities and differences between themselves and children in the global South (Allum et al., 2015: 23). The researchers noted in the post-programme session an increased ability to describe and discuss nuanced differences in skin tone and hair colour. It is tempting to attribute this change to activities in the Just Children resource. However, in an interview, the teacher mentioned her recent classroom work with diversity dolls and role-play about physical similarities and differences. The learning evident in the post-programme activity could not be attributed definitively to Just Children, nor to the diversity dolls, nor indeed to other influences. Research and evaluation in this case suggest that Just Children contributed to and enhanced the children’s learning, which is as far as a ‘result’ can be attributed to a particular DE activity.

Usually results-based approaches aim to identify and attribute impact but, in educational practice, it is not possible nor is it desirable to demonstrate causal links. If carefully used, pre- and post-programme activities can serve as a window onto learning or as part of a multi-strand evaluation. However, any toolkit or evaluation methodology based on comparing ‘before’ and ‘after’ data runs the danger of appearing to deliver clear evidence of change and there is a need to be vigilant about its limitations. One author of this article remembers vividly arriving late and frazzled at a DE conference, which was reflected in her pre-assessment tool while her post-assessment was calm and reasonable. How is the evaluation of such data to be read, analysed and reported on? It was not the DE event itself that calmed her. Likewise, the role of socially desirable responses and bias (Callegaro, 2008) in evaluation forms must be considered When participants and learners know the funding for the DE programme is related to the evaluation, it is likely they will be less critical and more positive in their assessments.

The impact of DE is what funders want to be able to demonstrate and ‘prove’; however, this impact cannot be solely accredited to the DE intervention. Media, family and community, global events, as well as other learning programmes can all play a role in generating the ‘result’. Some of these factors can be named, others are unexpected. Who would have known a year ago that we would all become so knowledgeable in global health pandemics and disease transmission?

The limitations in the use of results-based approaches to prove results and impact miss the other gains and positives that can be attributed to the DE work. The right form of evaluation and right questions just need to be asked. Tools for tracking DE at the level of the learner need to be appropriate for the work. Firstly, tools need to be capable of handling the complex attitudinal learning outcomes characteristic of DE. Secondly, tools need to respect the participatory, learner-centred values base of DE (Bourn, 2014). Thirdly, while tools that capture an action taken as a result of learning are very valuable, we also require tools that recognise that not all learning is accompanied by a short-term action or a visible change of behaviour. Reflection on learning and taking time to integrate new knowledge into established beliefs and behaviours can be challenging and long-term (Liddy, 2020).

How has DE in Ireland responded and adapted to use of RBAs

To help balance the need for measurable results with the need to do justice to rich DE learning, IDEA developed a hands-on toolkit for using RBAs in DE settings, and have updated the toolkit annually (IDEA, 2019a). Furthermore, Irish Aid staff have provided detailed feedback to funded organisations and have encouraged applicants to move beyond purely quantitative measures towards more qualitative measures in their RFs (IDEA, 2019b). IDEA’s Quality and Impact Working Group also played an important role in engaging with Irish Aid staff on the data collected using RBAs in DE. This dialogue has been very helpful as it takes place outside of the direct funder-funded power dynamic and provided feedback on the PMF data generated by Irish Aid. The use of qualitative indicators and anecdotal reporting (Collins and Pommerening, 2014) of positive learning outcomes were two of the areas of results reporting that Irish Aid now recognise and welcome in the annual reporting process.

However, there are many issues which require further exploration and reflection. Using results frameworks because they are a necessity for funding can lead to a mechanical repetition of what was accepted by the donor in previous years. Furthermore, as organisations understandably are averse to risking an empty results column at the end of the year, they may choose ‘safe’ indicators that rarely explore diffuse, long-term or cumulative impact. The root causes of poverty and injustice are complex topics; what organisation would claim that ‘challenging white privilege’ or ‘ending global hunger’ as their intended result, when ‘increasing awareness of racism’ or ‘learning about food security’ is a more realistic statement, especially as the funding is for just one year.

This choice of safe indicators has implications not only for how we measure our DE work, but also for the DE content of our programmes. There is truth to the maxim, ‘what gets measured, gets done’; if we choose ‘safe’ indicators over innovative ones, then creative DE can be squeezed out by more formulaic projects. This process then perpetuates the ongoing deradicalisation and de-clawing of DE (Bryan, 2011).

Responses by DE sector

The DE sector in Ireland has come a long way in creating and refining such tools. One example is the Self-Assessment Tool (SAT) used by WorldWise Global Schools, Ireland’s national Global Citizenship Education programme for Post-Primary Schools (2019). The SAT allows students and teachers to self-score across four learning areas: knowledge, skills, attitudes/values, and action. The before and after scores in the four areas can be collated to give a composite picture of learning in the school, and potentially can give an indication of how the WWGS-funded learning programme has contributed to changes in the school. In addition, the SAT contains an activity for students and teachers to record qualitative responses on their key learning in relation to these four learning areas, in the form of four key questions. It is important to note that the SAT is intended primarily as a tool for learning within schools and only secondarily as a way to measure the impact of the WWGS programme. It is also worth noting that the SAT is quite formal in its language and framing, as it was designed for use in a post-primary school setting.

Another example of an innovative approach to generating data for a RF is Trócaire’s (2018) Empathy Scale. This is a numerical scale designed to track depth of engagement in the complex learning area of empathy. The Empathy Scale is applied to work submitted by learners, such as games submitted into the Trócaire (2019) Gamechangers competition, and results are then fed into Trócaire’s DE Results Framework. The Empathy Scale is valuable in that it is based on ‘showing’ rather than ‘telling’; it uses evidence gleaned from materials produced by learners, rather than relying on learners’ self-reported responses to survey questions. However, it is recognised that the scale is inherently subjective in terms of the assessors’ interpretations of learners’ materials, and which is also influenced by many external contextual factors, such as teachers, peers and media.

Although it is designed as a tool for the practice of DE and not purely for evaluation, the new IDEA Code of Good Practice for Development Education (IDEA, 2019c) offers an opportunity for the sector to articulate good practice of quality DE and potentially illustrate the impact of DE work. A strength to this approach is that the identification of good practice is carried out in a way that is compatible with DE ethos, defined in the Code as ‘global solidarity, empathy and partnership, and challenging unequal power relations across all issues we work on’ (IDEA, 2019c: 14). Through the Code process, members self-assess the quality of their DE practice and identify evidence to illustrate specific good practice indicators. For example, Principle Four encourages critical thinking in exploring global issues and one attendant indicator asks if diverse and challenging perspectives from both local and global contexts are included. In the accompanying handbook, DE practitioners and organisations can describe the evidence they have (such as supporting documentation, policies, meeting details, photos, programme plans), as well as rate themselves on a four-point scale from minimal to full ability to meet this indicator.

The evidence gathered in the Code process could be collated to show how the provision of quality DE is creating a collective impact in target groups across the sector. Practitioners self-assessment through the Code could become one element of a broader evaluation of DE work, including perspectives of the learners, and more objective results can be obtained by just applying the RBA. This evidence could illustrate, rather than prove, the impact of quality DE on learners, and would be an educationally-appropriate tool for demonstrating the power of DE.

Questions for the way forward

Results-Based Approaches can play an important part in DE at institutional and programme level; these approaches can track successes and highlight areas to refine in further evaluation work. They also work well at individual level when the culmination of a programme involves taking a specific and measurable action. However, this paper highlighted some of the challenges that emerge if we attempt to apply a RBA to an attitudinal learning and values based learning programme (Bourn, 2014). In these cases, tools are problematic, interpretation of data is ambiguous, and attribution of change is next to impossible.

Standardised surveys, such as some of the templates offered in the Annex to the Irish Aid PMF (Irish Aid, 2017) can provide ready-to-use statistics to populate a Results Framework, but do they serve the needs of learners or of DE practitioners? In a one-hour workshop, is it really worth asking participants to spend valuable minutes at the start of the session rating their knowledge or skills, and then spend more time repeating the process at the end of the 60 minutes? Do these ratings contribute to an understanding of the ‘impact’ of DE? And more significantly, do these duties surrounding these measures occupy the ‘monitoring and evaluation space’ and thereby distract from creating more meaningful methods? If the sector continued to apply RBAs rigorously to the aspects of DE work to which they are suited (e.g. levels of stakeholder engagement or measuring depth of integration) could their use move away from unsuitable contexts? Instead of wasting time and energy on clunky pre- and post-programme measurements of learning at individual level, why not invest time, resources and innovative thinking into other ways of demonstrating that ‘DE works’?

In terms of funders who may seek more impact measurement data, the DE community needs to press for an acknowledgement that at best, pre- and post- measurements of learning will yield data about contribution, not about attribution. Funders also need to be more realistic about the level of change that can be expected to take place over the brief timespan of most DE initiatives. Robust longitudinal studies are extremely costly; for example, the ESRI (Economic and Social Research Institute) Growing Up In Ireland study has cost the taxpayer approximately €2.5 million per year (Wayman, 2018). Yet we cannot adequately deliver data about the long-term impact of DE learning without longitudinal research. Large-scale research funding could address many of the issues raised earlier and work towards the application of appropriate measurement and evaluation tools for DE learning, and find the right tools for the job.

The opportunity to explore some innovative approaches would be welcomed by the DE sector; however, research funding is key. The Mid-term Review of the Irish Aid DE Strategy has been paused due to the Covid-19 pandemic, but we hope it will resume in Autumn 2020. The IDEA Quality and Impact Working Group has prepared a submission for this review, outlining many of the difficulties we see in the usage of RBAs in DE and with recommendations to improve its awkward framework. However, this submission strongly suggests and encourages Irish Aid to examine other evaluation and learning tools, particularly for use in their new strategy beyond 2023. Furthermore, this research could link with Ireland’s reporting responsibilities under SDG 4.7; ‘the essential knowledge and skills’ for sustainable development. These knowledge and skills are not yet fully outlined (Gallwey, 2016) and the appropriate measurement tools need to be progressed to meet our reporting commitments.

Conclusion

Since 2012, RBAs have become central to evaluation in DE work in Ireland as a compulsory requirement by Irish Aid as part of the evaluation mechanism established for its development education grants scheme. While the DE sector has adapted to this, the use of RBAs in education is not without question or concerns.

DE practitioners in Ireland acknowledge the need for evidence to support their work, to improve quality, and to argue for ongoing resourcing and funding to continue their work. But quantitative numerical measures of results do not fully embrace the extent and range of DE work and they do not fully engage with learners’ responses. They do not measure or describe the full range of pedagogical processes involved in teaching or facilitating learning. There are many varied outcomes from a DE programme, from knowledge gain to attitudinal change to activism for positive social good. Use of a formulaic assessment and evaluation tool can miss the richness of individual case studies of learning and the overall vibrancy of the DE sector in Ireland. Unexpected or unintended positive consequences may be lost. Balancing the need for robust data as a form of accountability in the use of public funds with the richness and energy of the DE sector in Ireland is required by DE practitioners, not just Irish Aid.

As Chambers (1997: 55) argued about measuring poverty, ‘it is then the reductionist, controlled, simplified and quantified construction which becomes reality for the isolated professional, not that other world, out there’… where ‘the flat shadows of that reality that they, prisoners of their professionalism, fashion for themselves’. Through negotiation with the funding body and their innovative practices, the DE sector in Ireland can stay out of these flat shadows.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper are members of the IDEA Quality and Impact Working Group. We would like to acknowledge all other members of the group as this paper reflects many of the groups’ workplans, discussions and thoughts over the past few years. However, the ideas presented here are the opinions and experiences of the authors and are not the official view of IDEA.

References

Allum, L, Dral, P, Galanska, N, Lowe, B, Navojsky, A, Pelimanni, P, Robinson, L, Skalicka, P, and Zemanova, B (2015) How Do We Know It’s Working: Tracking Changes in Pupils’ Attitudes, Reading: Reading International Solidarity Centre.

Andreotti, V (2006) ‘Soft versus critical global citizenship education’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 3, Autumn, pp. 40-51.

Bourn, D (2014) Theory and Practice of Development Education, Oxford: Routledge.

Bryan, A (2011) ‘Another cog in the anti-politics machine? The “de-clawing” of development education’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 12, Spring, pp. 1-14.

Callegaro, M (2008) ‘Social Desirability, from the Encyclopaedia of Survey Research Methods’, in P J Lavrakas (ed.) Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods, New York: Sage Publications, pp. 826-827.

Chambers, R (1997) Whose Reality Counts? Putting the First Last, London: Intermediate Technology Publications.

Collins, A. and Pommerening, D (2014) Anecdotal Evidence Record, Oxford: DP Evaluation.

Dunkerly-Bean, J, Bean, T, Sunday, K and Summers, R (2017) ‘Poverty is Two Coins: Young children explore social justice through reading and art’, The Reading Teacher, Vol. 70, Issue 6, pp. 679-688.

Freire, P (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York, Continuum.

Gallwey, S and Mallon, B (2019) ‘Can a story make a difference? Exploring the impact of an early childhood global justice storysack’, Beyond the Single Story Intercultural Education Conference, 25 January, Dublin: DCU.

Gallwey, S (2016) ‘Capturing Transformative Change in Education: The challenge of tracking progress towards SDG Target 4.7’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 23, Autumn, pp. 124-138.

Gallwey, S (2013) ‘Using a Ruler to Measure a Change of Heart? Working with Results Frameworks in Development Education’, 20 November, Global Justice through Global Citizenship, Brussels: DEEEP/Concord.

IDEA (2019a) Using Results-Based Approaches in Development Education Settings: A Practical Toolkit, Dublin: IDEA, available: https://www.ideaonline.ie/uploads/files/Impact_Measurement_Toolkit_2020_FINAL.pdf (accessed 15 June 2020).

IDEA (2019b) ‘Notes from meeting with Irish Aid DE staff and IDEA Quality & Impact Working Group’, 10 June, Dublin: IDEA.

IDEA (2019c) ‘Code of Good Practice for Development Education’, Dublin: IDEA, available: https://www.ideaonline.ie/uploads/files/A4_Code_Principles_Landscape_web.pdf (accessed 15 June 2020).

Irish Aid (2006) Irish Aid and Development Education: describing... understanding... challenging: the story of human development in today’s world, Dublin: Irish Aid, available: https://www.developmenteducation.ie/teachers-and-educators/transition-year/DevEd_Explained/Resources/Irish-aid-book.pdf (accessed 15 June 2020).

Irish Aid (2017) Development Education Strategy Performance Management Framework 2017-2023, Dublin: Irish Aid, available: https://www.irishaid.ie/media/irishaid/allwebsitemedia/60aboutirishaid/Irish-Aid-DevEd-Strategy-PMF.pdf (accessed 15 June 2020).

Irish Aid (2018) Annual Report 2018, Dublin: Irish Aid, available: https://www.irishaid.ie/media/irishaid/DFAT_IrishAid_AR_V14-CC-SCREEN.pdf (accessed 15 June 2020).

Irish Aid (2019) Development Education Grant 2020 Application Form, Dublin: Irish Aid, available: https://www.irishaid.ie/what-we-do/who-we-work-with/civil-society/development-education-funding/ (accessed 16 October 2019).

Liddy, M (2020) ‘Apprenticeship of Reflexivity’, in D Bourn (ed.) The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education and Learning, London: Bloomsbury.

Lynch K, Grummell B and Devine D (2012) New Managerialism in Education: Commercialization, Carelessness and Gender, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lynch, K (2014) ‘“New managerialism” in education: the organisational form of neoliberalism’, openDemocracy, 16 September, available: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/new-managerialism-in-education-organisa... (accessed 26 August 2020).

Oberman, R (2010) Just Children: A resource pack for exploring global justice in early childhood education, Dublin: Trócaire and the Centre for Human Rights and Citizenship Education.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2002) Glossary of Key Terms in Evaluation and Results-Based Management, Paris: OECD.

Trócaire (2018) ‘Empathy and Understanding Scales for Development Education’, Maynooth: Trócaire.

Trócaire (2019) ‘Gamechangers Competition’, Maynooth: Trócaire, available: https://www.trocaire.org/education/gamechangers (accessed 13 August 2020).

UN Secretariat (2006) Definition of basic concepts and terminologies in governance and public administration, New York: UN, available: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/566603?ln=en (accessed 15 June 2020).

Vähämäki, J, Schmidt, M and Molander, J (2011) Results Based Management in Development Cooperation, Stockholm: Riksbankens Jubileumsfond.

Wayman, S (2018) ‘Growing Up in Ireland: what we’ve learned from a decade of research’, Irish Times, 7 November, available: https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/health-family/parenting/growing-up-in-ireland-what-we-ve-learned-from-a-decade-of-research-1.3676695 (accessed 15 June 2020).

WorldWise Global Schools (2019) ‘Self-Assessment Tool’, Dublin: WWGS, available: http://www.worldwiseschools.ie/tools/ (accessed 15 June 2020).

Mags Liddy was recently awarded the Nano Nagle Newman Fellowship in Education at University College Dublin (UCD) to study school leadership in developing world contexts. She is also Convenor of the Irish Development Education Association (IDEA) Quality and Impact Working Group. Contact magslid@gmail.com

Susan Gallwey has worked in development education for over 20 years, and recently retired from her position as Development Education Officer at Trócaire. She has a long-standing interest in creating appropriate and workable methods for the evaluation of development education. Contact details: susankgallwey@gmail.com