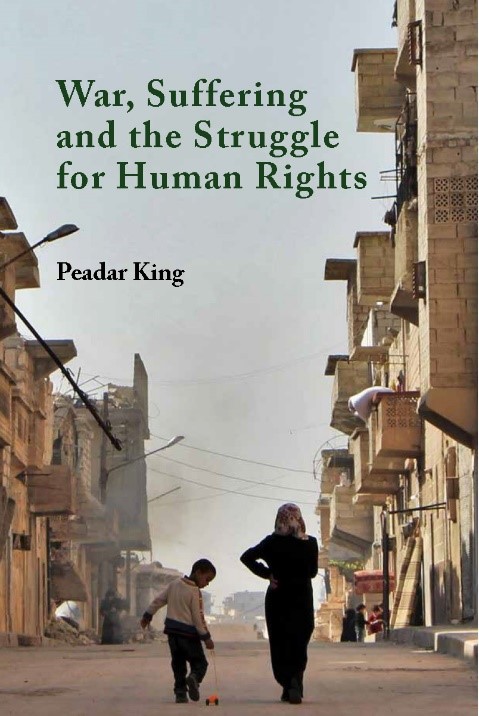

War, Suffering and the Struggle for Human Rights

The Policy Environment for Development Education

King, P (2020) War, Suffering and the Struggle for Human Rights, Dublin: Liffey Press.

Lebanese film-maker Nadine Labaki’s extraordinary and compelling Capernaum (2018) was an unexpected global sensation. Starring a 13-year-old protagonist who was himself a refugee and also starring, even more improbably, a child of three who becomes his sidekick, the film painted an unforgettable portrait of a chaotic, violent city (Beirut) where life is cheap, danger is everywhere, people are routinely sold and trafficked, crime is a way of life and your own family may be the most dangerous place of all. In this world there is no security and no safety net. Described by a Daily Telegraph reviewer as a ‘social-realist blockbuster – fired by furious compassion and teeming with sorrow, yet strewn with diamond-shards of beauty, wit and hope’ (Collin, 2019), the city portrayed, Beirut (in the news just now for very specific and tragic reasons), could in truth be any city with a legacy of conflict in the global South, from Mogadishu to Kabul.

Labaki’s brilliant film showed, in a visceral way, the everyday struggle for survival of tens of millions living on this planet today. If done well, as it was in this case, that is one of the great strengths of the medium of film - a sense of immediacy, visual power, and empathetic identification with the characters. But how does one achieve the necessary distancing required to stand back in a more reflective, analytical fashion and write about such issues, and what might be the purpose of writing about them? This is the challenge addressed by Peadar King in War, Suffering and the Struggle for Human Rights. King, long-time producer and presenter of What in the World?, Irish national broadcaster RTÉ’s global affairs series, has been bringing astonishing stories into Irish homes for almost 20 years. From stories of hope and inspiration to stories of oppression and suppression, the series has examined lives lived amongst serious and persistent poverty, and a wide range of complex social and political situations across the developing world.

It is not an easy task to address such issues on a global scale. Descriptions of injustice, violence and inequality are challenging at the best of times. They are most readily understood through real-life case studies, but when one begins to catalogue the horrors which humankind can inflict on itself, several dilemmas quickly become evident.

For one thing, the sheer repetitive awfulness of any such telling can numb the senses. As King says, in a sentence attributed to Stalin, one death is a tragedy, a million a statistic. There is a danger that the recitation of events will become a case of one damned thing after another, desensitising the reader and ultimately making it difficult to formulate an adequate moral, political or even emotional response. Robert Fisk reminds us of conversations with United States officers in Iraq after the invasion of that country in 2003 when they ‘began to talk to us of “compassion fatigue”. Outrageously, this meant that the West was in danger of walking away from human suffering’ (Fisk, 2020).

The stance to be adopted by any putative writer-as-witness to this apparently never-ending nightmare also poses a challenge. Can injustice, war, violence and suffering be adequately captured and analysed by any observer, especially one who has not been a participant in or direct observer of the events portrayed? How can one combine human empathy with dispassionate analysis and consideration of the underlying political and structural factors giving rise to such evils in the first place? Is it to be an unrelieved portrait of bleakness and savagery and is there a danger that a glint of humanity or hope might dilute this message? How does the writer allow space for readers to formulate their own responses to such recitations?

Of course, these problems and dilemmas are not new. They are part of the journalist’s daily calling. If their task is to write the first draft of history, that should include all of the above; disinterested accuracy and informed, dispassionate analysis and commentary. One might also include the academic researcher, who attempts, one hopes equally dispassionately, to analyse the causes and consequences of human, social and political events, whether at a local level or on a global scale, while situating that analysis within a broader comparative perspective.

The French word vulgarisation is not easy to translate – ‘popularisation’ is the usual English language equivalent, although words like ‘outreach’ and ‘dissemination’ are also suggested. The meaning is very far from what might be suggested by an overly literal English language reading and actually conveys, with a positive connotation, the notion of the dissemination of a high degree of knowledge and expertise in a form accessible to a wider public audience. This is a key element of King’s book. It combines the first-hand observations typical of good journalism, carried out in the field and based on encountering many of those directly affected, with background analysis and factual knowledge based on careful research. While he does not dissemble his own rights-based, left-of-centre political standpoint, that does not inhibit his ability to call out wrongdoing wherever he sees it. He has a keen eye for human detail, a strong empathy with his subjects and the background expertise to make sense of what he sees in both its specific and broader contexts.

His focus is a global one. In thirteen chapters, he manages to paint a portrait of some of the world’s more troubled places, as disparate as Afghanistan, Lebanon, Brazil and South Sudan. Some will be familiar, others, such as Western Sahara and Uruguay, less so (at least to the English language reader). Even in the case of those places and situations we think we know, he conveys a specificity of focus and an analytical depth that goes beyond what one might encounter in standard media reports. Moreover, one of his constant themes is, precisely, that much of what we think we know about such places is itself often derived from a radically inadequate, clichéd and distorted media image which serves to obfuscate and reduce complexity, rather than elucidate and educate. I remember all too well from my own time living in Lebanon in the 1980s that the part of the city where I lived, west Beirut, was almost invariably preceded by the qualifiers ‘mainly Muslim’ or ‘war-torn’. Such shorthand usages offer a superficial picture of a complex place and actually get in the way of a proper understanding, as surely as the constant depiction, familiar but irritating to Irish people, of the troubles on this island as a war between Catholics and Protestants.

King also shows that the lacunae in western media coverage are not limited to the clichés used, but affect the basic choices made in what is considered newsworthy and reportable. After one atrocity in South Sudan involving the massacre of about 2,000 civilians, he contacts a radio station in Ireland.

“That sounds like an interesting three minutes’, I was told. ‘Perhaps on Friday’. It didn’t happen. Apparently Friday was a busy day in Ireland. And, we are told, black lives matter” (194).

This picture of the Western perspective on the rest of the world may lack the bitter irony of the title of war correspondent Ed Behr’s (1978) memoir Anyone Here Been Raped and Speaks English? but the point is not dissimilar.

Certain themes recur throughout the book. One is man’s inhumanity to women: for example, the mass killing of women in the Mexican border town of Juárez which began around 1993.

“Many victims were teenage students, poor and working-class young women. According to an Amnesty International (2003), the majority of the victims were less than eighteen years old and almost half of them were subjected to sexual violence beyond the basic act of rape. Many had bite marks, stab wounds, ligature and strangulation marks on their necks. Some had their breasts severely mutilated. Autopsies determined that some of the missing girls were kept alive for a few weeks before being murdered. Investigators believe the girls were held captive and repeatedly raped and tortured before being murdered. Posters plastered on city walls bear testimony to the scale of the killing” (96-97).

This is not the only way in which women are victimised. King’s description of the links between militarisation and exploitative sex work around US military bases in South Korea takes us on a tour of the subject, going back to earlier versions of such exploitation in nineteenth century Ireland and drawing on the work of historian Maria Luddy concerning the Contagious Diseases Acts 1864-1886, which provided for the forcible confinement of up to nine months of women (but not men) suffering from venereal diseases in ‘subjected districts’ including Cork, Queenstown (Cobh) and the Curragh.

In spite of the book’s avowed subject matter, it is still a shock to read of the sheer levels of violence and murder portrayed. Latin America stands out – home to just eight per cent of the world’s population, but 33 per cent of its homicides.

“More than 2.5 million Latin Americans have been murdered since the turn of this century. No other continent comes near. Just four countries in the region – Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela – account for a quarter of all the murders on Earth” (27).

King does not reach for any simplistic explanations but nor does he subscribe to the idea that there is anything inexplicable about such matters. The world he portrays is rotten with inequality, corrupted by criminal drug gangs (serving, of course, western consumers in more salubrious countries) and controlled by ideologues like Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, sharing, as the book notes, the same white supremacist ideology as his North American neighbour.

Some issues surface repeatedly, including the often calamitous consequences of military intervention by outside powers in places such as Libya. But while every chapter also contains examples of survivors and the courage of those who fight for just causes, one offers a glimpse of the possibility of a genuinely better society. It is the story of José Alberto Mujica Cordano (‘Pepe’), former president of Latin America’s second smallest country, Uruguay, and a former revolutionary, inspired by Ché Guevara. A modest man known throughout the continent, he was responsible for a number of radical social experiments, including the legalisation of marijuana, and for policies in areas such as health and education which seem to have done much to reduce social inequality and oppression in Uruguay. It is probably no coincidence that a country known for its vibrant participatory democracy, low inequality and expansive social policies also stood out in its response to the recent COVID-19 pandemic.

The prose style is informal, direct and down-to-earth – sometimes perhaps excessively so – rather than academic and references are not provided. It could be argued that a focus on fewer places and in greater depth, rather than a world-wide whistle-stop tour, might have been more productive, but a good case can also be made for the choices King has made here.

I thought this book would be rather daunting, if only because of its endless accounts of human rights abuses and injustice. But King also shows the art that conceals art. Each chapter of about twenty pages is a self-contained account, painting a picture of people and places in a way which leaves the reader informed, interested and anxious to find out more. But each chapter also echoes common themes, in a way which conveys a continuity and an internal unity of purpose. He clearly writes with an Irish readership in mind, but what he has to say should be of interest to a far wider audience as well.

Above all, it is not all unremitting horror. He also shows us that humanity, resilience, tolerance and goodwill are rarely absent from the grimmest of situations. He amply justifies the task he has set himself, to make sense for us, the readers, of the places he depicts, to recover the humanity and agency of those portrayed, including victims, and to encourage us to think about our own moral engagement with the world beyond our shores, while subtly and constantly reminding us, should there be any danger of smugness or complacency, of local parallels.

References

Amnesty International (2003) Intolerable killings: 10 years of abductions and murder of women in Ciudad Juárez and Chihuahua, available: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/amr41/026/2003/en/ (accessed 10 August 2020).

Behr, E (1978) Anyone Here Been Raped and Speaks English?, London: New English Library Ltd.

Collin, R (2019) ‘Capernaum review: a crazily ambitious, heart-in-mouth neorealist version of Baby’s Day Out’, The Telegraph, 21 February, available: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/films/0/capernaum-review-crazily-ambitious-heart-in-mouth-neorealist/ (accessed 10 August 2020).

Fisk, R (2020) ‘Beirut has suffered a catastrophe that will live long in the memory – and the repeated betrayal of its citizens is a travesty’, 5 August, The Independent.

Labaki, N (2018) Capernaüm, available: https://www.capernaum.film/ (accessed 10 August 2020).

Piaras Mac Éinrí lectures in migration and geopolitics in the Department of Geography at University College Cork. He is a former member of the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs, with postings in Brussels, Beirut and Paris.