Justice Dialogue for Grassroots Transition

Rethinking Critical Approaches to Global and Development Education

Abstract: This article deals with how a community conversation about transitional justice in a disadvantaged and deeply divided area of North Belfast led to the publication of a grassroots toolkit that is now translated into Arabic and Spanish for others to use in their own settings (Rooney, 2012). The toolkit aims to empower, equip and encourage people to examine the local practicalities of transition in a social justice conversation about the future. The article contributes to a growing interest in grassroots activism in development and transitional justice studies (Lundy and McGovern, 2008; McCloskey, 2014). I argue that the toolkit is a rights- based programme that supports local action, social repair and community transformation.

Key words: Transitional Justice; Toolkit; Conflict; North Belfast; Development Education; Community Change.

Introduction

What happens in a local district when a peace agreement is reached that brings an end to a protracted violent conflict? After the international spotlight turns away, how do people in a divided society get on with day-to-day life? What happens in women’s groups that have worked across the divide? In a situation where political progress is stalled and uncertain and when accountability for past human rights violations is resisted and contentious, how are the pressures of transition managed on the ground? Are there ways that the experience of living through a conflict can be utilised as a resource for social repair? Some answers to these questions were considered in a conversation about transitional justice in North Belfast that was convened by Irene Sherry, Head of Mental Health Services in Ashton Trust’s Bridge of Hope. As a community activist and member of the Transitional Justice Institute at Ulster University, I was invited to facilitate. The conversation became the basis for designing the Transitional Justice Grassroots Toolkit (Rooney, 2012) so that others could join in and have their say. The workbook and guide are freely available online in Arabic, English and Spanish for others to use in their own settings (Transitional Justice Institute, n.d.).

The experience of post-conflict transition in resource limited circumstances is of major interest to social justice academics and activists in development and transitional justice studies (Lundy and McGovern, 2008; McCloskey, 2014). This article argues that the toolkit can be adapted to support community dialogue in other troubled and politically divided circumstances. Using it, participants examine the local challenges of transition and consider what needs to happen next. Disadvantaged urban areas of Northern Ireland, like those in North Belfast where the toolkit conversation started, experienced disproportionate concentrations of human rights violations during the thirty-year conflict (Fay et al., 1999). When the conversation started in January 2011, the local peace process was already the subject of a substantial and influential literature. It was viewed globally as a remarkable twentieth century success story (Campbell and Connolly, 2003). Its influence continues to flourish (The Irish Times, 10 December 2016). This grassroots exchange, however, looked at the process from a very different angle. The initial conversation involved political ex-prisoners and former members of the IRA, UDA and UVF. The conversation began with the question ‘what is transitional justice and what can it do for us?’ The programme that ensued was the basis for designing the toolkit. Two women’s groups from republican and loyalist districts tested it and recommended a user’s guide. The groups had worked across the political divide for more than twenty years and yet the toolkit programme was the first time they had ever talked about their conflict experience (Magee and Sherry, 2017).

The men and women who participated in the early dialogue were all experienced community activists involved in truth seeking campaigns, women’s issues, trauma services and restorative justice (Rooney and Swaine, 2012). Restorative justice promotes alternative approaches to violent punishment for crime in local communities (Gormally, 2015). Hence, these participants were already active in the bottom- up transition processes of working with victims and survivors and engaging in post-conflict community transformation. The toolkit offered an opportunity for them to exchange views on their conflict experience and the impacts of the 1998 Belfast Agreement (Gov.uk, n.d.), which ended thirty years of conflict in Northern Ireland. The kind of post-conflict grassroots activism toolkit participants engage in is generally overlooked in transitional justice research (McEvoy and McGregor, 2008). It amounts to community ‘change from within’ and it occurs informally in troubled circumstances everywhere (Collier, 2007: 12). Grassroots organising empowers the people concerned and can help to improve life where it is organised. The toolkit programme engages with and informs this local agency.

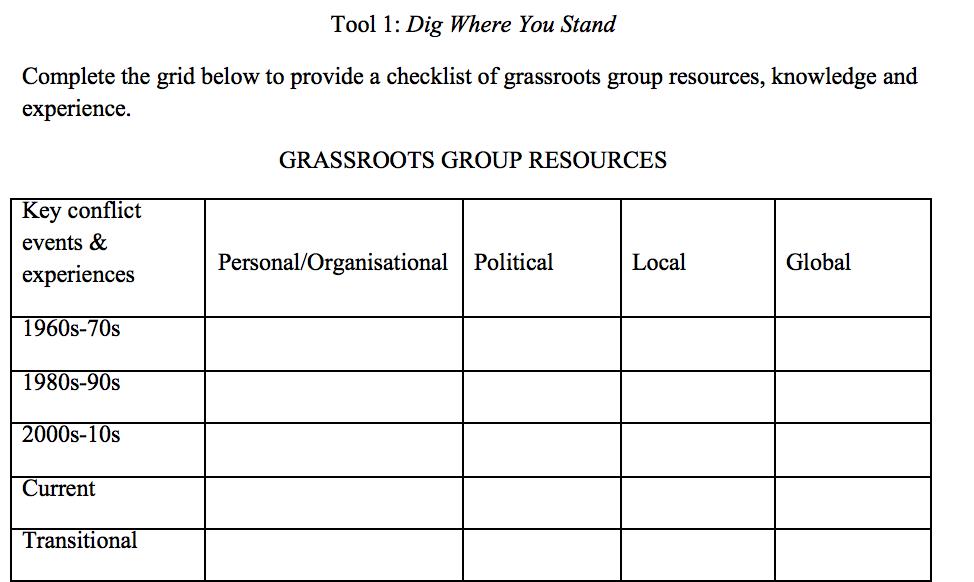

Altogether, the workbook has eight tools and a full programme usually consists of one session for each. The title of Tool 1, ‘Dig Where You Stand’, is a shorthand description of toolkit pedagogy. Everyone using Tool 1 is asked to reflect on their local conflict experience and make brief notes in the grid (see Tool 1 below). Individual grids are compiled into a single grid that represents the resources that everyone brings to the programme. The second tool introduces transitional justice in a five-pillar framework. The pillars are: institutional reform, that involves changes to public institutions intended to right past wrongs; truth, that addresses how a society deals with accountability for human rights violations; reparation refers to forms of social repair that are normally made to victims and their families; reconciliation addresses harm done to social relationships as a result of armed conflict; prosecution and amnesty relates to legal and other ways of bringing an end to armed violence and encouraging actors to tell what happened. Each measure is the title of the five tools that follow. The last tool (Tool 8), ‘Map Making’, is where everyone makes a map of the local transition and its milestones. The programme ends by looking to the future and thinking about what needs to happen next.

Part one of this article outlines the context for the initial toolkit conversation and introduces the toolkit’s simple and radical ‘dig where you stand’ pedagogy. Part two illustrates how some tools have been used. In part three, I reflect on intersectionality as the conceptual pivot of the toolkit design and method. A note on takeaways for the development educator precedes my conclusion on the remarkable necessity of seeing hope as a practical form of agency in the context of local frustrations and a growing sense of global despair.

Part 1: Place for conversation

Like many democratic states across the globe, the origins of Northern Ireland lie in violent conflict. The British partition of Ireland in 1922 established a majority unionist (mainly Protestant) and a minority nationalist (mainly Catholic) population. Institutionalised sectarianism led to civil rights protests in the 1960s and 70s. The reforms that quickly followed arguably inaugurated a long-term process of transitional justice. Collective amnesia to its past might have prevailed in Northern Ireland as it does elsewhere. The statelet might have developed differently but for the violent reaction to street protests that escalated into repression and armed conflict. The armed conflict that followed was not inevitable either. Neither was the peace agreement that was reached in 1998. Over thirty years of conflict, around 3,700 lives were lost. This loss of life in a small population of approximately 1.5 million people was immense and concentrated in the poorest urban areas of Belfast and Londonderry/Derry where over 80 per cent of conflict fatalities occurred. The number of attributed losses between 1969 and 2001 calculated by Sutton (2002) are: British Army (297); Royal Ulster Constabulary (55); UDA (262); UVF (483); and IRA (1,822). The IRA, UDA and UVF emerged from within the public housing estates of the most disadvantaged nationalist/republican and unionist/loyalist districts. Most of the British Army soldiers on the ground at the time of the conflict came from disadvantaged urban areas of Great Britain.

In the lengthening post-conflict context, the toolkit conversation contributes to a grassroots peace- building process that was politically inspired by the ceasefires and is community led. North Belfast is the most politically polarised and segregated constituency in Northern Ireland. Here, disadvantaged districts form a patchwork of close-knit streets that are blockaded at political interfaces. One in five conflict- related fatalities occurred here. The legacy of the conflict, along with the impacts of austerity, welfare reform and Brexit border uncertainties, makes life harder for everyone in these districts (Committee on the Administration of Justice, 2006; Bell and McVeigh, 2016). Additionally, at the time of writing, the local devolved power- sharing assembly created under the 1998 Agreement has not met since January 2017. The political impasse has hampered decision-making initiatives that could help to address urgent social and economic difficulties.

At first sight, North Belfast appears to be the least likely setting for a grassroots transitional justice toolkit to take root and thrive. And yet, it did. The simple pedagogical practice that made it possible can be adapted for other challenging conversations in different contexts. The participation of motivated individuals and groups with community credibility is critical. In the initial conversation, the first lesson for everyone was to listen. For instance, when the first participants spoke of their background, loyalist men said that they saw themselves as ex-combatants. Republican men and women said that they saw themselves as former volunteers and politically motivated ex-prisoners. For an outsider, these self-descriptions may be an interesting curiosity or useful analytical concepts for research. For the people who make these distinctions, however, much more is at stake.

The words that people use in these circumstances are often invested with self-worth, communal dignity and political purpose. For instance, loyalists refer to ‘Northern Ireland’ whilst republicans refer to the ‘North of Ireland’. The terms assert and challenge the settled status of the constitution and rights within the United Kingdom. This is about much more than petty political point scoring. The language used in a toolkit conversation reflects complex cultural values, views on rights and equality plus the human and political vulnerabilities of participants. Respect and openness to the words people use helps to diffuse divisiveness that could get in the way of an inclusive dialogue. No-one is excluded. Anyone interested can join in and feel free to use words and decide on meanings that work for them. This is peace- building at a pace that is decided by the people involved. The ‘dig where you stand’ method ensures that language is not a barrier to listening. In the initial conversation, everyone eventually agreed that the terms ‘Northern Ireland’ and the ‘North of Ireland’ could be used alternately throughout toolkit publications. For some people, reaching this consensus was a significant act of political generosity and recognition.

Local listening

Attentive listening is more than a facilitator skill or participatory practice. It is based on the principles of fairness and respect for human dignity that are central to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Rights- based toolkit practice involves watchful respect, awareness of silences and encouragement. This means noticing the ways that people participate non-verbally. A skilled facilitator can encourage attentive listening as a form of self-empowering participation. This has a levelling effect that was noticeable in the initial conversation between ex-prisoners, especially when someone talked about themselves as a young man or woman, growing up in a working class republican or loyalist district and having experiences that led to them becoming ‘involved’ (i.e. active and armed). These situating-of-self stories help to explain the leadership role that some participants still hold within their own communities. Their organisations, they maintained, had a galvanising, peacebuilding role that is not recognised either in the local media or in academic research. Participants from loyalist districts, in particular, saw the transitional justice conversation as a way to counter a negative public image that recycles bad news stories in the media. For instance, public blame for sectarian strife or racist attacks in North Belfast commonly fails to focus on worsening social and economic conditions that compel a more complex public response and wider social responsibility.

The toolkit is not about blame. It simplifies academic patois and provides an opportunity for researchers to engage with toolkit groups on their research into one of the pillars (Rooney, 2012). Toolkit groups are generally keen to hear and engage with academic perspectives and recommendations that might directly affect them. They are introduced to transitional justice in a presentation that tracks its mid-twentieth century origins to the International Criminal Court at Nuremberg (ibid: 43-44). Its twenty-first century revival is explained as an outcome of the post-Cold War and post-9/11 global environments. Peace Agreements are a central feature of post-conflict transitions. Around 1,500 agreements were negotiated in 150 jurisdictions between 1990 and 2016 (Political Settlements Research Programme, n.d.). The five- pillar framework has proved to be adept for introducing an array of complex transition measures applied in various post-conflict contexts. Examples of each are introduced in a quick ‘I get it’ way in the guide. Local power-sharing is the example given for ‘institutional reform’; the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission is an example for ‘truth’; material or symbolic restitution is the generic example for ‘reparation’; participatory community programmes are a simple example of ‘reconciliation’; the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia is the example used for ‘prosecution and amnesty’.

The original conversation between loyalists and republicans was hard working and free of contention though not free of dispute. Political positions were well- known, and, whilst difficult subjects were not avoided, neither were they an occasion for confrontation. Less straightforward were the exchanges between the two loyalist groups. From an outsider perspective, one loyalist or republican community may appear to be very much like another. However, this early conversation revealed what insiders already knew. That is, that each district has its own particular gendered history of human rights violations, armed insurrection, paramilitary factionalism and government neglect. These experiences run very deep in the areas concerned. In the past, they have led to fractured relationships within families and between neighbourhoods where different factions of an organisation hold sway. The toolkit makes space for these tensions to surface safely. That in itself was a significant toolkit achievement in the original Bridge of Hope conversation.

These North Belfast grassroots communities do not see themselves as without internal resources. Nor are they wholly dependent on external agencies to resolve serious post-conflict problems. On the contrary, people using the toolkit recognise that the local management of political expectation and the mobilisation of community disaffection are potent political forces that can heal relationships, build peace or undermine political stability. This gritty reality is inconsistent with most mainstream liberal peace theory that remains grossly optimistic about the potential of top down interventions to resolve conflict and make peace work (Tziarras, 2012).

Part 2: Dig Where You Stand

Given the opportunity to use the toolkit, participants reflect, listen and engage in a dialogue about a wider social landscape of reduced resources and political pressures that make social repair harder for everyone. They decide for themselves what can be said, what can be done and what is possible given the pressures in a particular locality. Imagination is important too. Some participants respond more readily to images rather than to information in a text. One photograph at the start of the user’s guide, for instance, shows eight faces of people of various ages, genders and skin colour (Rooney, 2014: 6). The image is described as representing common humanity as, ‘a multiplicity of perspectives, class backgrounds, religions and regions’ (Rooney, 2015: 74). In an opening session, this photograph is used to spark discussion on individual distinctiveness as a common human resource that in some circumstances serves as a reason for exclusion and conflict.

The first tool asks everyone to ‘dig where you stand’; in other words, to situate ‘yourself’ by thinking about, ‘the experiences and events that make you the person you are’ (Rooney 2014: 20). It is a simple request that is often tackled with relish. Intersectional positions quickly emerge. Working singly or together, women, young people, ex-prisoners, and conflict victims and survivors, along with a facilitator, make notes in the grid. They record gendered, class and community-based conflict experience, knowledge and resourcefulness.

The grid is set out this way: five time periods make up the left side with four headings across the top. The time periods are flexible and changeable according to the age range in a group of participants. The scaled down Tool 1 grid below starts at the 1960s through to the present. The headings are: personal/organisational, political, local, and global. At a glance, a life and a social history can be captured in short hand.

Source: The Transitional Justice Grassroots Toolkit (Rooney, 2012: 11).

The idea of Tool 1 is to quickly make a chart of some individual and communal milestones and memories. At the end of the session grids are collected and collated for the next session. The collated Tool 1 grid is a record of the group’s social resources. No name appears on any grid. This allows users to record an experience or event that someone sees as important but contentious or difficult to be spoken of openly. People often note a conflict experience that is linked to their political and geographical location. Hot topics of the moment often surface, such as welfare reform or Brexit (Magee and Sherry, 2017). Tool anonymity is used to critical effect. In one session, a participant wrote: ‘my father was interned when I was a kid’. Another, simply ‘the Shankill bomb’. And another ‘we were put out of our home in the 60s’. In that same session, someone else wrote ‘my brother was killed’. None of these statements was said aloud or owned by anyone in the group at the time but everyone saw the grids and learned something about what had happened to another person. Each toolkit programme teaches that everything does not have to be spoken of to be understood or acknowledged. Anonymous communication is an input that has a potent impact (ibid).

At the end of a recent programme, one woman spoke up and said that a highlight of the toolkit for her was to be able to regard her conflict experience as a resource. Previously, she had viewed her bereavement as a personal one of loss and grief that she spent her life getting over and dealing with one way or another. When using the five-pillars, she said she drew on the experience and in this way saw herself as making a contribution to the toolkit group. Her generous approach was anticipated in the guide:

“[A]t the heart of this grassroots work … is an emphasis on local people and their lived experience. Contributions from those who endured the worst impacts of conflict have the potential to shape the journey of transition [for everyone]” (Rooney, 2014: 10).

The woman who spoke up found that she had used her experience in a self-empowering way of her own choosing. Her moving awareness silenced the room for a brief time. Such moments occur in each toolkit programme. Sometimes they occur when a tool grid that everyone has completed is passed around and a life changing event that someone has recorded is noted without comment. This is profound peace-building.

Some participants identify themselves primarily as victims and survivors. Being identified in this way is an official recognition that is often valued as necessary and beneficial for those who have suffered a conflict related bereavement or injury. Such recognition may carry policy standing and related reparation entitlements. However, there are downsides to being identified as a conflict ‘victim’ or indeed as an ex-prisoner or former combatant. These people may have few opportunities to express a wider sense of their own worth and agency. ‘Just’ using the tools, is a self-empowering way to participate. It is about going beyond the immediacy of personal experience and placing it within a wider context. This justice dialogue reflects on ‘what remains to be done’ in a life in a local area. How this is articulated and acted upon is up to people themselves. This is a creative programme with practical concerns about the impacts of transition in the everyday (Rooney, 2017). Each participant engages creatively in an exchange about social justice. This includes learning about how people in other transitions deal with complex justice dilemmas.

The self-empowerment method is transferable. When a Transitional Justice Institute (TJI) researcher used Tool 1 in an oral form in a Palestinian camp in Lebanon, the camp residents recounted family narratives of displacement over different decades (Sobout, 2017). They gave accounts of everyday acts of resistance and resilience. The institutional reform and reparation tools were used, as they are used in Belfast and elsewhere, in self-empowering ways of the user’s own choosing. These participants saw institutional reform as relevant to their experience of exclusion from decisions taken about the reconstruction of the previously bombed camp and they used reparation to reflect on their repeated experience of displacement and denial as rights bearing people. Camp residents used the toolkit to articulate the collective dignity that they invest in rituals of daily life and to imagine and map a reconstructed camp of the future (ibid.).

Global Glimpse

Whilst Tool 1 is where the toolkit methods of listening and being listened to are first practiced, Tool 2, “The Five Pillars – Global Glimpse”, turns everyone’s attention to transitions elsewhere in the world and how some of the five measures are employed in different settings. Attentiveness of another kind comes into play. Everyone is asked to refocus, to raise their eyes as it were, to the horizon of transitions across the globe. Five boxes make up the tool and are labelled: institutional reform, truth, reparation, reconciliation and prosecution and amnesty. The guide has some country examples alongside each. The gear shift from focusing on the familiar local to seeing how another place faces complex post-conflict challenges, has a liberating effect. Everyone is ‘in the same boat’ in the sense of relying on each other to share some knowledge about the five pillars and different places. The tool raises fundamental questions about where local ‘knowledge’ about other places comes from and how everyone relies on similar sources of media information. To help overcome any knowledge gaps, some academics and researchers from TJI filmed ten-minute talks on each of the pillars. The talks include local reflections, international examples and reliable websites. Some toolkit participants will focus on a particular country whilst others may identify a measure that matters to them and investigate how it has worked elsewhere. The key learning from the five tools that follow is that transition is tough and uncertain in any society recovering from a protracted period of violent, dehumanising politics.

Talking truth

The truth of what happened in the past in any conflict is bound to be controversial. Dealing with the past is often regarded as the most controversial subject facing a society in transition. Tool 4 tackles the truth about the past in a broad sense by inviting everyone to name three local and/or international truths that they see as necessary. They give reasons for their choice and name ways to find the truth in each case. Lastly, they note some pros and cons of finding the particular truth. The process of having to pin down reasons for and name ways to find a ‘truth’ and identifying some consequences allows everyone to see both the complexity of dealing with the past and the importance of singular and shared truth claims.

The truths named in the tool grid are rarely confined to human rights violations. Some people want the truth to be told about historical events and others about social and economic inequalities and political oppression in different sites. Some participants detail the local role of security force collusion with non-state loyalist militaries and with informers on all sides; also often noted are truths about religious institutions, the state, individual politicians, international mediators and the British and Irish governments. What’s useful about this broader canvas of ‘truth’ is the cognitive distance that emerges between ‘knowledge’ about the local and sources for learning about the global.

The workbook image for truth is a photo of old fashioned metal block letters once used in printing (Rooney, 2014: 10). Placed together, the letters read, ‘The truth’. The temporary placing of the letters for the photograph suggests that truth is itself put together or constructed from different elements. It may be captured in a photograph or on the web, put together in a report or established with forensic evidence in a court of law. The trainer’s manual reminds everyone that accountability for human rights violations is a lawful obligation (Rooney, 2015).

The truth tool session ends, like other sessions, by prompting intersectional awareness of personal and political positioning, about where participants stand in relation to being outsiders and glimpsing ‘truth’ that is required in another setting. An image from the guide that is framed as a jigsaw piece is used to expand on this awareness. It shows a set of photographs of the faces of people killed or disappeared in Latin America (Rooney, 2014: 34). The photographs make up a body shape as if in a crime scene investigation. It is difficult to look at the faces. Each one calls for a response. But there is no simple way to respond to the image without being curious about the people pictured and wanting to know more about their context. Ignorance of a context, however, can arouse empathy for people who are strangers to us. The trainer’s manual takes the point further:

“Imagination is a unique human ability that enables empathy with perspectives and experiences not our own. It enables us to picture a collective future that may seem impossible from where we stand at the moment. Picturing a different future is the first step to making it happen” (Rooney, 2015: 67).

Toolkit and guide images are used for purposes of creative and critical reflection around how taken-for-granted knowledge about both the local and the global are mediated by influential sources that establish ‘knowledge’ which goes unquestioned.

Part 3: The personal is intersectional

The last tool, Tool 8 ‘Map Making: From the Personal to the Political’ focuses on the role of equality and human rights in a transition. People are not expected to agree in advance as to what equality and rights mean any more than they have agreed on other terms. The point is to enable everyone to feel free to engage in a conversation about what they see as significant. The commitments to equality and human rights made in the 1998 Agreement are alluded to as transition landmarks and democratic obligations. Local realities are faced:

“The labels ‘Catholic’ and ‘Protestant’ are used in the North of Ireland as short-hand for a person’s relationship to the state ... Labels are a tricky, if handy, way to refer to a conflict. The labels ‘Catholic’ and ‘Protestant’ are necessary for monitoring equality [but] do not explain the full identity of people and who they truly are. Rather, they identify political and equality features of a society in conflict” (Rooney, 2014: 12).

The toolkit programme is infused with intersectional awareness. In practice, this means stressing the combined significance that gender, class and identity have in shaping individual conflict experience, justice aspirations and future hopes. The approach contributes to a relatively recent turn in transitional justice scholarship that is concerned with how justice and social repair are negotiated in daily life (Shaw and Waldorf, 2010). Two questions are posed at this juncture: how do people experience transitional justice processes that are presumed to be for their benefit? And, after conflict how do individuals and groups ‘restore the basic fabric of meaningful social life’ in ways that are relevant to their lives? (Alcalá and Baines, 2012: 385). These practical concerns and questions are at the core of toolkit conversations as well as central to the intersectional approach.

Intersectionality theory is a useful diagnostic tool for understanding community tensions in deeply divided, sectarianised jurisdictions where the resources required to tackle structural inequalities (e.g. in housing, education and income) are invariably refused, unavailable or contentious. Commitments made in a peace agreement to equality and rights are often contested when it comes to practical implementation. In some cases, law and social policy play a strong enforcement role. This is so, whether the site of the transition is security force reform in Belfast or accountability for human rights violations in Baghdad.

The responsibility and decisive role of governance in all of this is often obscured by research agendas and media fixations that concentrate on warring men. Recurring social unrest and threats of violence in places like North Belfast are rarely recognised as symptomatic of loyalist anxieties in a situation where the constitutional status will be decided by referendum at some point in the future. Institutional failures to implement negotiated equality and rights commitments in republican areas are on no-one’s agenda. Battles between policy implementation and claw back fuels a destabilising local competition for sectional resources and votes (Ní Aoláin and Rooney, 2007). The impacts on marginalised women’s lives often sink below the horizon (Rooney and Swaine, 2012). All of this is palpable in toolkit conversations.

Seeing women

When the women from the republican Falls Road and loyalist Shankill Road women’s centres were introduced to the five pillars of transitional justice, they independently gravitated to Tool 3 on institutional reform, and had plenty to say. Welfare reform was a top news story at the time and they were collectively incensed about the impacts of benefit cuts on women in their community. Welfare reform, however, is not regarded as a transition related reform in transitional justice theory. The women had a different view. They clearly saw that reduced resources would seriously affect women like themselves and they said it would adversely impact on their community’s capacity to manage change. The two groups enjoyed sharing their strongly held views, having a common purpose and saying what should be done next. They used tool anonymity to articulate things that might prove contentious if said aloud. When they completed the programme, they gave feedback and said that this was the first time in over 25 years of working together on a number of issues that they had ever met in each other’s centres. It was also, as already noted, the first time ever they had talked conflict politics together (Magee and Sherry, 2017).

There is a sense though, that ‘adding women’ to the post-conflict picture will, for the most part, make little difference. Reams of feminist theory have been written about this ‘adding women’ approach that makes no difference locally or internationally (Scott, 1996; O’Rourke, 2015). Critical points of feminist theory such as this one often surface pragmatically in toolkit conversations. These activist women saw themselves as making a difference a day in their centres. For most men doing the programme, the idea that gender is a shaping factor (or force) in their lives is usually viewed as something of a disruptive novelty rather than a practical and critical insight. The customary silence on gender as an intersectional shaping force in men’s lives, as well as in statistics on deaths in conflict, goes some way to explain these initial reactions.

For the most part, feminist and other social theory tends to be thought by toolkit groups as an elite academic activity, abstract and remote from the everyday. Everyday theory, however, refers to how knowledge is produced from practical experience and grassroots struggle (Bade, 2010). Toolkit participants theorise their own situations and engage with various forms of knowledge and struggle to do this. The toolkit conversations reveal an acute awareness of how an individual’s gender, social class and political position, shapes and, to a large extent, determines individual and collective experiences of conflict and transition. The toolkit makes the masculinity of gender and the hiddenness of women’s lives visible in text and image. For instance, women’s conflict experience and activism is emphasised in this common sense observation from the guide:

“Anyone’s experience of conflict and transition is shaped by a number of factors. Gender is an obvious one. It is so obvious that it is often overlooked [and] easy to forget … The gender impacts on women and men are rarely examined. The toolkit is a means to record these differences” (Rooney, 2014: 11).

Dignity in dialogue

One reason for the toolkit’s staying power and popularity is that local knowledge and experience are recognised as critical resources for the conversation. Everyone is an expert in their own life and times. Toolkit conversations develop a space where speaking out and listening are forms of active engagement. Toolkit groups are eager to tell of the impacts of conflict and transition in their own families and communities. Another reason that the conversation facilitates an educative exchange between former opponents and people with different political aspiration is that everyone recognises a common purpose in learning about transitions elsewhere. Everyone wants to learn of transition achievements and predicaments in other places. Participants inform themselves of international developments and use the opportunity to engage wider constituencies, including academics and NGOs, in a conversation about the past and the future.

Toolkit conversation is not an agreeable chat about social repair. It does not ease tensions and lessen competition for scarce public resources in disadvantaged districts. Nor, obviously, does it fix any of the complex accountability problems alluded to in this article. It does not set out to confront issues for the sake of confrontation, nor to persuade anyone of anything other than their entitlement to speak out, to be heard and to listen to others do the same. No-one is asked to forgo their aspirations. The toolkit conversation is arguably a form of social justice in practice. The focus is on institutions, official commitments and ways that power works rather than who people are in a group. Although, who people are is their critical starting point. The toolkit goes on to explore state and church founding institutional histories that constitute the conditions of everyday life. It admits the possibility of engaging in a social justice exchange that regards all participants as rights bearing, dignified equals. That is, as people who manage hostile socioeconomic structures of deep-rooted inequalities in a deeply divided polity that can do better.

Toolkit takeaways

The participatory method at the heart of this grassroots work is undoubtedly influenced by development education practice in the global South. Paulo Freire’s emancipatory pedagogy (Freire, 2001) was widely used across Northern Ireland in women’s groups and prisoner education throughout the conflict (Hope and Timmel, n.d.). Being steeped in this approach, I used it intuitively when facilitating the initial community conversation and designing the toolkit. Similarly, using intersectionality as a conceptual lens for a grassroots conversation in a divided society was a transitional justice borrowing from feminist critical race theory in the United States (Crenshaw, 1991; Rooney, 2018). The toolkit’s participatory pedagogy, then, is an example of practice and theory influences and borrowings coming together to support a local justice dialogue. How this is supported in Arabic, English and Spanish speaking settings is up to a facilitator who adapts the toolkit to local circumstances (Sobout, 2017). Listening to the language used and facilitating the freedom of diverse participants to use terms of their choice is a critical takeaway for the development educator intending to use the toolkit in oral or textual forms. Textual forms allow for grid anonymity.

A further takeaway is the transportability of the toolkit’s ‘Dig Where You Stand’ participatory pedagogy with its central recognition of the value of local knowledge, experience and imagination as resources for social repair. For this reason, Tool 1 is an indispensable starting point. The adaptability of the five- pillar framework is an additional takeaway. It was devised from listening to the topics raised at the initial conversation and linking them to international research in the global field of transitional justice. This local and global framing is adaptable for dialogue about other complex topics between people with conflicting experiences and perspectives. It involves using a simple grid to frame issues in meaningful and accessible ways that enable everyone to listen to each other and consider implications for action. For a development educator planning to use the toolkit, a final pragmatic takeaway is that the participation of individuals with community credibility is crucial. Their grassroots leadership encourages wider participation. In practice, the toolkit programme to date has been an educative and gratifying engagement between people who explore their local experience in the context of transition challenges across the globe.

Conclusion

The toolkit’s bottom-up beginnings, as a small budget one-off conversation designed around the simple principle of giving voice to grassroots conflict experience and concerns in North Belfast, proved to be pivotal. In the absence of major funding and free of funder commodification pressures, we developed a civic programme that puts local experience and participation at the heart of a justice conversation about post-conflict transition. This might not have happened, we may not have listened so closely, if the valid priority was to gather data, produce a commercial project or publish a report to meet time-bound objectives. As it transpired, in the process of facilitating a much needed local conversation, we focused on listening and using what was learned to build a dialogue that supports local peace building. We developed a unique community empowerment programme that is translatable to other grassroots circumstances. These seemingly accidental outcomes were the fruits of an effort to join people in taking action to maintain hope and change the script of their lives.

The word ‘hope’ is not often used in the necessarily hard headed socio-legal field of transitional justice. It will be treated with suspicion by some. I might have considered myself one such were it not for the experience of working with the Bridge of Hope and people in North Belfast. In this constituency, disadvantaged districts may have some political influence at the ballot box but they are without the power or prospect of gaining the structural investment that their areas desperately need. In these circumstances, people do what they can to improve family life and local conditions. The toolkit programme is a contribution to these endeavours.

Two images of hope from the guide capture the determination and necessity of sustaining hope in situations where despair might more readily overwhelm everyone. One shows Hope Street on a brick wall in Belfast city centre (Rooney, 2014: 50). The street has been redeveloped. Inner city homes have been demolished long ago. Everyone is asked to imagine what it is like to live in Hope Street, to have hope, and then to think about the impact of hopelessness in a community. The other image is a graffiti spattered wall in a war zone with the capital letters: ‘KNOW HOPE’ (Rooney, 2014: 46). The wordplay on ‘no hope’ rejects ignorance and affirms something of the power of knowledge as resilience in the midst of catastrophe. If hope is knowable in these dire circumstances, the graffiti artist seems to proclaim, then we must commit to knowing hope anywhere. This is hope in the Freirean sense of conscientisation (Freire, 2001). It is hope in Gramsci’s ‘good sense’ concept (Gramsci, 1971), rather than hope as misleading sentiment. This notion of knowing hope is fundamental to building and sustaining community resilience. No-one, whatever their background is, excluded. The toolkit programme is an educative engagement with the past that celebrates the pragmatic value of hope and community resilience for building a different future.

One risk of transitions from war to relative stability, however, is that the circumstances of those who have endured the most may be ignored and set aside. In a rush away from a contentious hard-to-deal-with past towards a nebulous reconciliation, the unexamined failures of the past may be pushed into a distant future to await fresh discovery perhaps by another excluded and disaffected generation without direct experience of conflict. This grassroots toolkit is a community-led commitment to hinder that prospect.

References

Alcalá, P R and Baines, E (2012) ‘Editorial Note’, International Journal of Transitional Justice, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 385-393, available: https://academic.oup.com/ijtj/article/6/3/385/683878 (accessed 4 June 2018).

Bade, S (2010) ‘Everyday Theorizing and the Construction of Knowledge’, Journal of Information, Intelligence and Knowledge, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 339-342.

Bell, C and McVeigh, R (2016) A Fresh Start for Equality? The Equality Impacts of the Stormont House Agreement on the ‘Two Main Communities’ – An Action Research Intervention, Belfast: Equality Coalition.

Campbell, C and Connolly, I (2003) ‘A Model for the "War on Terrorism?" Military Intervention in Northern Ireland and the Falls Curfew’, Journal of Law and Society, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 341-375.

Collier, P (2007) The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done About It, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) (2006) Equality in Northern Ireland: The rhetoric and the reality, Belfast: Committee on the Administration of Justice, available: https://caj.org.uk/2006/09/01/equality-northern-ireland-rethoric-reality/ (accessed 4 June 2018).

Crenshaw, K (1991) ‘Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color’, Stanford Law Review, Vol. 43, No. 6, pp. 1241-1299.

Fay, M T, Morrissey, M, Smyth, M and Wong, T (1999) The Cost of the Troubles Study: Report on the Northern Ireland survey: the experience and impact of the Troubles, Derry Londonderry: INCORE.

Freire, P (2001) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th Anniversary Edition, New York: Continuum.

Gormally, B (2015) ‘In the midst of violence: local engagement with armed groups, Conciliation Resources’, available: http://www.c-r.org/accord/engaging-armed-groups-insight/northern-ireland-punishment-restorative-justice-northern (accessed 4 June 2018).

Gov.uk (n.d.) ‘The Belfast Agreement’, available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-belfast-agreement (accessed 20 July 2018).

Gramsci, A (1971) Selections From The Prison Notebooks, translated and edited by Q Hoare and G N Smith (1999), London: The Electric Book Company, available: http://courses.justice.eku.edu/pls330_louis/docs/gramsci-prison-notebooks-vol1.pdf(accessed 4 June 2018).

Hope, A and Timmel, S (n.d.) Key Principles of Freire, Belfast: School of Unity and Liberation, available: https://www.ivaw.org/sites/default/files/documents/Key%20Principles%20of%20Freire.pdf (accessed 21 July 2018).

Lundy, P and McGovern, M (2008) ‘Whose Justice? Rethinking Transitional Justice from the Bottom Up’, Journal of Law and Society, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 265-92.

Magee, A and Sherry, I (2017) Bridge of Hope Toolkit Archive [unpublished].

McCloskey, S (2014) ‘Introduction: Transformative Learning in the Age of Neoliberalism’ in S McCloskey (ed.) Development Education in Policy and Practice, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

McEvoy, K and McGregor, L (2008) Transitional Justice from Below: Grassroots Activism and the Struggle for Change, Oxford: Hart.

Ní Aoláin, F and Rooney, E (2007) ‘Under-enforcement and Intersectionality: Gendered Aspects of Transition for Women’, International Journal of Transitional Justice, Vol.1, No. 3, pp. 338-354.

O’Rourke, C (2015) ‘Feminist scholarship in transitional justice: a de-politicising impulse?’ Women’s Studies International Forum, Vol. 51, pp. 118-127.

Political Settlements Research Programme (n.d.) Peace Agreements Database, available: https://www.peaceagreements.org/search (accessed 20 July 2018).

Rooney, E (2012) Transitional Justice Grassroots Toolkit, Belfast: Bridge of Hope, available: https://www.ulster.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/231710/75856R660TRANSITIONAL-JUSTICE-TOOLKIT112017.pdf (accessed 20 July 2018)

Rooney, E (2014) Transitional Justice Grassroots Toolkit: Users’ Guide, Belfast: Bridge of Hope, available:

https://www.ulster.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/231712/75856R658TJI-USER-GUIDE112017.pdf (accessed 20 July 2018).

Rooney, E (2015) Transitional Justice Grassroots Toolkit: Trainer’s Manual, Belfast: Bridge of Hope.

Rooney, E (2017) ‘Justice Learning in Transition: A Grassroots Toolkit’, Political Settlements Research Programme Working Paper Series, No. 18-02, pp. 1-33, available:

http://www.politicalsettlements.org/publications-database/justice-learning-in-transition/ (accessed 4 June 2018).

Rooney, E (2018) ‘Intersectionality: Working in Conflict’, in F Ní Aoláin, N Cahn, D F Haynes, and N Valji, (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Conflict, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rooney, E and Swaine, A (2012) ‘The “Long Grass” of Agreements: Promise, Theory and Practice’, International Criminal Law Review, Vol. 12, pp. 519-548.

Scott, J W (1996) Feminism and History, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shaw, R and Waldorf, L (2010) Localizing Transitional Justice: Interventions and Priorities after Mass Violence, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Sobout, A (2017) ‘Planning for Peace’, Belfast: Ulster University.

Sutton, M (2002) Updated and revised Index of Deaths from the Conflict in Ireland, available: http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/sutton/book/index.html (accessed 2 July 2018).

The Irish Times (2016) ‘Colombia’s Peace Deal Drew Inspiration from Northern Ireland – Country’s President’, 10 December, available:

http://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/colombia-s-peace-deal-drew-inspiration-from-northern-ireland-country-s-president-1.2901322 (accessed 26 March 2018).

Transitional Justice Institute (n.d.), Toolkit – Grassroots Transitional Justice Programme, available: https://www.ulster.ac.uk/research/institutes/transitional-justice-institute/research/current-projects/t4t-toolkit (accessed 20 July 2018).

Tziarras, Z (2012) ‘Liberal Peace and Peace-Building: Another Critque’, The GW Global Post Research Paper, available:

https://thegwpost.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/liberal-peace-and-peace-building-zenonas-tziarras-20123.pdf (accessed 4 June 2018).

Acknowledgement

My thanks go to Irene Sherry at the Bridge of Hope for leading the way. Also to Dr. Joanna McMinn for invaluable support in the final stages of this article. Gratitude is also due to the following Transitional Justice Institute colleagues and researchers for their voluntary contributions to the DVD: Rimona Afshar, Louise Mallinder, Rory O’Connell, Catherine O’Rourke, Bill Rolston and Elizabeth Super. Thanks also go to Ulster University’s Paul Notman who made the DVD with funding obtained by the Bridge of Hope. The toolkit translations were supported by the Political Settlements Research Programme (PSRP: www.politicalsettlements.org) funded by UK Aid from the Department for International Development for the benefit of developing countries. The views set out here and any errors made are mine alone.

Eilish Rooney is a feminist community activist who teaches in the School of Applied Social and Policy Sciences and is a member of the Transitional Justice Institute at Ulster University.