Global Education can Foster the Vision and Ethos of Catholic Secondary Schools in Ireland

Rethinking Critical Approaches to Global and Development Education

Abstract: There are currently 374 voluntary secondary schools in Ireland constituting 51 per cent of all post-primary schools (CSO, 2018). Until the 1960s, these schools were staffed primarily by religious sisters, brothers and priests. The decline in available religious personnel has meant that they are now run by education trusts who must keep the mission and values of the founders alive in the schools. As a teacher in a fee-paying Catholic secondary school, I realise that the principles of global education (GE) are closely aligned with the stated ethos of my school which has strong aspirations towards social justice. I have become convinced of the potential that GE has to promote and maintain the founding vision and ethos of the school and of all religious schools. I believe that it could greatly increase the likelihood of our Catholic schools producing young men and women to be agents of transformation in society and in the world. I feel that this is particularly important in schools like mine as graduates of fee-paying schools are considered to have the potential to wield influence in society (Freyne, 2013).

The aim of my study was to investigate the potential of GE to foster the founding vision and ethos of Catholic secondary schools in Ireland. Through questionnaires and semi-structured interviews, I elicited the opinions of teachers and principals in three fee-paying Catholic secondary schools in Dublin. For convenience, I chose to include my own school in the study, also selecting two other schools belonging to different religious orders. A total of 225 teachers from these schools received an online Survey Monkey questionnaire and seventy-four completed it, which was a response rate of thirty-three per cent. Respondents were invited to provide contact details if they wished to be interviewed. Of the twelve teachers who responded, nine were selected for interview based on their subjects. As religion, senior geography and Civic, Social and Political Education (CSPE) were identified in the literature as being the subjects most likely to involve GE the sample included at least one of each. The three principals were also interviewed.

As fee-paying Catholic schools in Dublin cater for only a certain demographic of the Irish population, the results are therefore biased in terms of the socio-economic background characteristic of the students. Despite this and although the selection cannot be considered representative of all Irish secondary schools, the study is likely to be of interest to teachers and educationalists in other settings and it is potentially applicable to many Irish post-primary schools.

Key words: Global Education; Development Education; Catholic Ethos; Secondary Schools.

Introduction

As educators, we have a wonderful opportunity to influence our students for good, to make them aware of injustice, to teach them the critical skills to analyse its underlying causes and to care enough to want to bring about change. Global education can help us to achieve this as it aims to develop awareness, compassion and critical thinking skills which in turn lead to action for justice. GE is closely linked to, and is often considered to be synonymous with, development education (DE) (Godwin, 1997). The terms are often used interchangeably as the significant content dimension of DE is a focus on the global (Dillon, 2016). In this article both terms are used. The Maastricht Declaration (2002) offered the following definition for GE:

“Global Education is education that opens people’s eyes and minds to the realities of the world, and awakens them to bring about a world of greater justice, equity and human rights for all. Global Education is understood to encompass Development Education, Human Rights Education, Education for Sustainability, Education for Peace and Conflict Prevention and Intercultural Education; being the global dimensions of Education for Citizenship” (EWGEC, 2002: 2).

Catholic ethos and social justice

Statements from the websites of some of Dublin’s fee-paying Catholic schools express the aspiration that their students will become agents for change in society.

“Most importantly, we encourage our school community to look outwards and become agents for social change through involvement in initiatives supporting justice”.

“Our work on the goal of Social Awareness has given our pupils the appropriate knowledge, values, skills and opportunities to enable them to effectively address injustice, conflict-resolution and environmental issues and thus become ‘agents of transformation’”.

“The many social justice programmes help nurture a lifelong desire to work towards a fairer, more just society”.

The aspiration that the students should become positive agents of change in society indicates that the principles of GE are largely in line with the Catholic ethos expressed by the schools on their web sites.

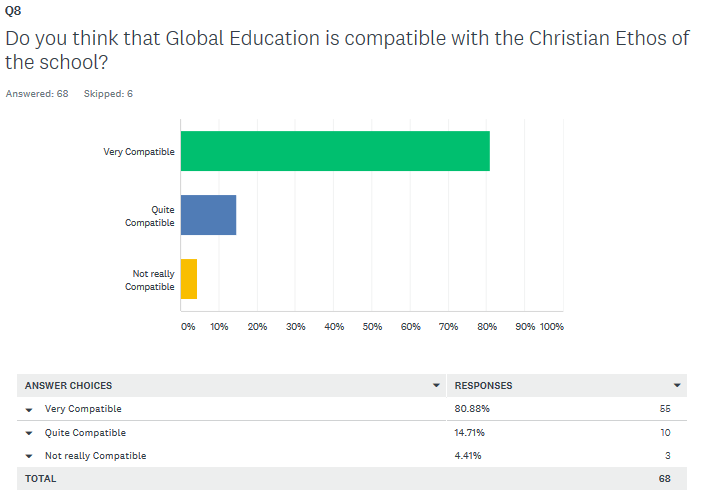

This mirrored the opinions of the teachers in the study. When asked the question ‘Do you think that Global Education is compatible with the Christian Ethos of the school?, a significant 96 per cent of teachers responding to the questionnaire believed that GE was compatible with the ethos of their schools and 89 per cent felt that it would be of benefit to students and staff. In interviews, all teachers expressed the view that the Catholic ethos of the school was compatible with the principles of GE. This echoes the findings of Bryan and Bracken (2011) as teachers spoke about the need for schools to produce well-rounded, socially conscious individuals and viewed development education as having an important role to play in this process.

Figure 1: Do you think that Global Education is compatible with the Christian Ethos of the school?

In fact, one principal and a teacher from a different school expressed the hope that GE might play a role in faith formation as there is no longer a significant presence of religiously professed staff in the school. Principal Laura said: ‘That’s why I think the whole idea of Global Education is really important. I think it’s a very strong way of developing young people in their faith’. Religious Education (RE) teacher Brendan made a similar point:

“I suppose for people who would be less religious in their outlook I think Global Education is a way of expressing the ethos of the school in a modern way…Schools should definitely promote it as a way of living out the ethos of the school”.

Involvement in social justice work and developing a social conscience might forge a path to faith and could help to foster a Catholic ethos while traditional practice of faith is in decline.

Global education in the curriculum

It is clear that committed and sustained engagement with GE would enable schools to engage with their Catholic ethos. It is obvious from this research, however, that the greater body of teachers do not have a good understanding or much experience of GE. In the surveys, a slight majority, 53 per cent, said that they had never taught it and 38 per cent were not aware of any other teachers’ involvement with GE. Honan (2006) thought that DE had advanced from its origins as a marginal ‘tag-on’ and had ‘come in from the cold’, with both its content and methodologies evident across the curriculum (ibid: 20). The new Leaving Certificate subject, Politics and Society, piloted in forty-one schools and examined for the first time in 2018, has great potential as it aims to develop the student's ability to be a reflective and active citizen (DES, 2016). DE is also specifically addressed in subjects such as junior and senior cycle, religion, geography and CSPE. In interviews it emerged that many teachers think that GE is taught in these subjects, but is this really the case?

CSPE is a subject well suited to a rich exploration of DE (Honan, 2006) but, as concepts must be explored in a single 40minute period per week, there is a clear message that development and global justice themes are simply not that important. According to Jeffers, the allocation of one class a week to CSPE creates ‘an impression that, no matter what the rhetoric, the subject can’t be very important’ (2008: 6). CSPE teacher Geraldine said: ‘We’re definitely limited with the fact that it’s one period a week. You get very, very little done. You’re really teaching to the exam and that’s not what Global Education should be about’.

Adam made the same point:

“It’s one period a week. You have to get a lot of stuff done in a small period of time. You can’t limit Global Education to CSPE or religion as you don’t have enough time. That’s the bottom line”.

CSPE will be examined for the last time as a stand-alone subject in 2019. It will instead be incorporated into a new Junior Cycle subject called Wellbeing (NCCA 2017), which will possibly allow for deeper exploration of GE material. Brendan teaches Leaving Certificate religion but avoids the GE content:

“I’ll be honest, the current Leaving Cert religion programme is so dense that it’s very hard to cover the course. When you’re faced with getting them through the exam you become more pragmatic and choose what’s more applicable to the exam”.

Geraldine teaches Leaving Certificate geography, which includes GE in economic geography. Other opportunities to study GE are lost, however, because the topics are perceived as an exam risk. Geraldine explains:

“Schools avoid global interdependence as the marking is vague. It goes back to teachers teaching for the exam. The other options are geo-ecology. It’s physical geography, it’s black or white. It’s either right or wrong”.

As she marks Leaving Certificate geography she knows that this is a nation-wide trend:

“I could get three hundred scripts and they’d all do geo-ecology. It goes back to the marking of it and the fact that it’s physical geography. Students find it more straightforward to learn point after point after point”.

Fiedler et al. (2011) had noted this point. They cited Bryan and Bracken (2011) who found that DE opportunities are hindered by a system that ‘marginalises global themes, privileges recall and outputs over learning, and provides little time or space for self-reflective interrogation’ (Fiedler et al., 2011: 60). All three schools participating in this study regularly top the lists of ‘feeder-schools’ to Irish universities and are consistently in the top ten of the nationwide school league tables. Teachers believe that they can’t focus on GE issues because parents are more concerned about results. Freya said: ‘I hear this from parents; it’s focused on the Junior Cert, the Junior Cert, the Junior Cert. In the exam year, the focus is on the exam’. Ciaran felt the same pressure:

“Losing more time would be a huge burden for me. Well, being a fee-paying school we have to get good results. If we were at the bottom of the league table I don’t think too many parents would be paying fees”.

Cross curricular teaching and a whole-school approach

It has been found that GE is largely promoted and supported by individuals or small groups of teachers within a school and there is very little engagement by school staff as a whole (Gleeson et al., 2007). Many schools rely on ‘champion’ or ‘warrior’ teachers to push GE (Rickard et al., 2013: 40). It is clear that a whole-school approach in which GE is taught across the curriculum is the ideal (IDEA, 2013). Change needs to be part of a wider vision or ethos and implemented through strong and committed support from senior leadership within the school (Bourn, 2016). If new DE activity is incorporated into existing school activities it is less likely to be rejected (Rickard et al., 2013). Unless this happens, it may be championed by just one enthusiastic and committed person but this is not sustainable in the long run (Doggett et al., 2016).

Teacher support

To engage the wider school community, training in good practice and methodologies is essential (Kruesmann, 2015). If this support is not provided: ‘teacher educators run the risk of reinforcing – rather than challenging – unequal power relations and colonial assumptions and promoting uncritical forms of development action’ (Bryan and Bracken, 2011: 41). The willingness and capacity of school management to support teachers in DE endeavours is crucial. Yet Rickard et al. (2013) found that per cent of school principals do not include DE as part of their staff planning days and the idea of introducing DE as part of these days evoked very little interest.

Not all teachers will want to engage with DE. Some have been working in their own area for so long that cross-curricular work may prove difficult: ‘the price of a strong ethos of teacher autonomy can be a culture of teacher isolation’ (Jeffers, 2008: 8). Doggett et al. also referred to the traditional ‘silo’ approach of the individual teacher in the classroom which leads to isolation and stasis (2016: 58). Not everybody will perceive a need to change the status quo. As Bourn noted: ‘any discussion on teachers as agents of change needs to be predicated on an understanding of the limitations many teachers face in their desire to be agents of change’ (2016: 68). Others may be reluctant to bring DE into their subject, seeing it as a disservice to students preparing for high-stakes examinations (Bryan and Bracken, 2011: 187).

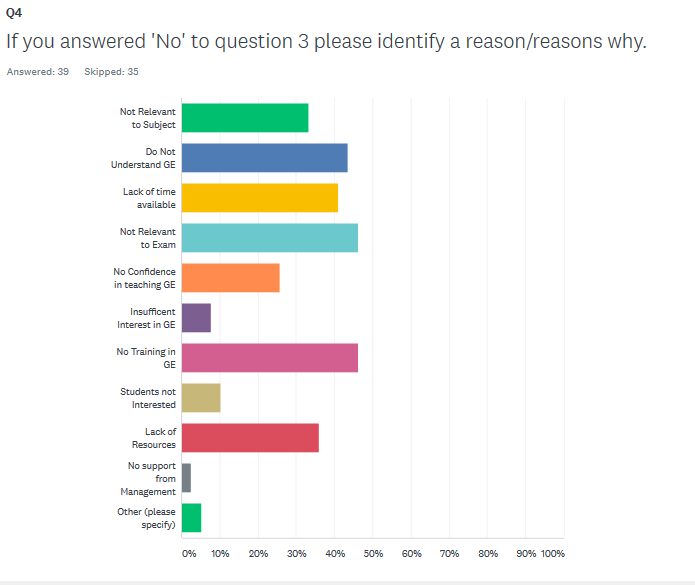

When asked in the questionnaire why they didn’t teach GE, 46 per cent of teachers surveyed felt that it was not relevant to state exams and 41 per cent did not have the time to teach it. This indicates that ‘teaching to the exam’ was a major factor in their failure to engage with GE. Other reasons cited were lack of understanding of GE and lack of training and resources. This points to the need for staff training and investment in the area. Both the data and the literature agree that to successfully embed GE into the life of the school the impetus must come from the top down. Management must champion global education, allowing time for whole staff training on principles and methodologies and making it part of school mission and policy. The narrow focus on academic excellence and examinations in many schools prevents this from happening.

(Question 3 was “Have you taught Global Education in your own subject area?”)

Figure 2: If you answered ‘No’ to question 3 please identify a reason/reasons why.

Global education and charity

The questionnaire asked teachers to select one or more options from GE activities that they may have observed in their schools. Eighty seven per cent considered fundraising for charities and sixty three per cent considered overseas immersion trips to be examples of GE, thus indicating a poor understanding of the concept. This was closely followed by: ‘Talks by Aid Workers’, The ‘Trócaire Lenten Campaign’, The ‘Concern Debate’ a ‘WorldWise Global Schools (WWGS) Workshop’ and development workshops by Irish Aid and Trócaire.

Many schools practise what Bryan and Bracken (2011) described as ‘development as charity’. The three schools participating in this study are very active in works of charity and many charitable organisations and beneficiaries are very grateful for their support. White, as cited in Cleary (2015: 57) considered DE to be an education that focuses on social justice, moving away from the ‘charity model’ to one of active global citizenship where students engage with social justice issues. When fundraising is seen as a legitimate response to global poverty, this reinforces stereotypical ideas about the dependency and vulnerability of recipients who are in need of ‘our’ help and does little to promote a more substantively equal relationship between the global North and global South (Bryan and Bracken, 2011: 231). It places those in the North in a position of power, creating a seemingly kind and benevolent master but a master nonetheless (Simpson, 2017). Concentrating solely on a fundraising agenda to alleviate poverty insulates learners from having to re-think dominant understandings as it shields them with comforting assurances that they are helping to ‘make a difference’ (Bryan and Bracken, 2011: 207). Also, the sense of achievement that is derived from fundraising activities may close off the possibility of young people thinking further about, and acting to change, the structures that bring about and sustain poverty and injustice in the first place.

In interviews teachers felt that fundraising was a positive and even necessary activity but many teachers felt that the approach to fundraising could be better. Brendan said:

“I think kids fundraise and don’t really know what they’re fundraising for. There has been an over-emphasis on the charity which is important but probably we need to get away from that, we need to break that link that it’s all about charity”.

Sometimes awareness is lacking. Eamon said:

“I sometimes wonder if they know what they’re buying that cake for, trying to make the school understand as they’re killing each other to get to the tables. I think we could have more awareness”.

Doggett et al. found this attitude in school leaders also: ‘the charitable approach expressed by many school leaders enabled greater distancing and an aspirational stance rather than active involvement in Development Education’ (2016: 47).

School immersion trips and global education

All three schools involved in this study bring students to countries of the global South on immersion trips where they may visit projects, attend school or participate in voluntary work. In all three schools, an important element of the trip is to provide financial assistance to the projects visited or to the associated charity organisation and they involve huge fundraising campaigns.

Bryan and Bracken (2011), however, found that school links initiated for charitable reasons are counterproductive to the aims of GE and can reinforce stereotypical thinking which can lead to feelings of intellectual and moral superiority. These trips may belong to the development-as-charity framework, which positions Irish participants as ‘global good guys’ and southern participants as needy recipients of ‘our help’ (ibid: 28). Given the long-standing and embedded nature of charitable initiatives in Irish post-primary schools and their pervasiveness as an accessible and ‘doable’ form of development activism, a considerable challenge exists in steering schools and students away from helping approaches and towards a mutual learning approach to school-linking and immersion schemes (ibid: 252). School partnerships should be on an equal footing, based on mutual learning and not charity (IDEA, 2013) but this is rarely the case.

The missionary ethos

This ‘helping’ model relates back to the missionary ethos of the founders of these schools when Irish nuns and priests went to the global South to teach, nurse and to spread Catholicism. While some believe that missionaries were instrumental in bringing a social justice perspective to the emerging DE agenda, others believe that missionaries and church or parish-based groups were prominent in influencing the discourse on the developing world from a charity perspective by concentrating on ‘starving black babies’ (Fiedler et al, 2011: 18). O’ Sullivan (2007), as cited in Fiedler et al. (2011), noted that:

“The Irish missionary movement created a vivid, albeit at times inaccurate, image of Africa in the minds of the Irish population. The ‘penny for a black baby’ campaign called on Irish citizens to support missionary societies building schools, hospitals and churches in their parishes” (ibid: 17).

Principal John said:

“We were taught primarily by priests and they talked about buying a black baby, paying a penny for a black baby…. I’d be very conscious as a lay Principal of my responsibility to maintain the wishes of the founding fathers”.

It is obvious that this attitude has survived to the present time. The overseas immersion trip is afforded great prominence as it reflects the missionary intent of the founding orders. As those early missionaries saw no need to question the validity of their actions, neither is the validity of sending teenagers to the global South to ‘do good work’ often questioned either. According to this model, going on mission is desirable in itself, without the need for intense preparation or questioning why this charity is necessary. In fact, some have questioned whether all school activities are purely altruistic. According to Bryan and Bracken, these types of schools are more likely to practise ‘high profile’ DE, which enhances the overall reputation of the schools and enables them to demonstrate that they are offering a ‘well-rounded education’ to their students (2011: 160). Tallon et al. (2016) also found that social action in schools might promote the status of the school in the community rather than active social change agendas.

Although the teachers interviewed did not consider the trips to the global South to be cynical exercises in promoting the school, on some occasions the lack of preparation and apparent purpose led them to question the value of such trips. In two of the schools in the study teachers voiced concern that there was insufficient preparation before trips and that GE opportunities are lost when students come home. On the other hand, the third school’s preparation programme and reciprocity through exchange meets the good volunteering standards as set out by Comhlámh (2017). Other schools could learn from their example.

Promoting action for change

It is significant that definitions of GE and DE share a commitment to critical thinking leading to action. Tormey noted that all modern definitions of DE contain references to ‘critical thinking/awareness/reflection’ as well as ‘action’ (2003: 214). Definitions across the board appear to agree that DE should result in behavioural change on the part of the learner (McCloskey, 2016). McCloskey (2016) related this to Freire’s ‘liberating action’. Freire’s conception of social transformation is intrinsically linked to the concept of ‘praxis’ which is a combination of reflection and action. This reflection leads to empowerment and determination to bring about change and highlights the importance of engaging in quality GE in our secondary schools. If we really want our young people to become agents for change in the world, we must empower them with the skill to think critically, with an awareness of injustice and a desire to overcome it.

Do Irish secondary schools produce ‘Agents for Change’?

Some of the teachers interviewed were not convinced that their schools are producing agents for change. Brendan said:

“I don’t know that we’re making critical thinkers and people that will challenge as journalists maybe or solicitors. I’m not sure that we’ve achieved that yet. We do showcases, we do projects and displays but sometimes they’re on a superficial level”.

Bryan and Bracken also found that, in the school context, calls to action generally involve ‘obedient activism’ ‘whereby students are channelled into apolitical, uncritical actions such as signing in-school petitions, designing posters or buying Fairtrade products’ (2011: 16). Often experiences of service and social action at school are limited to feasible short-term projects, and often under the umbrella of fundraising. As Tallon et al. suggested, this kind of activity is often more concerned with ‘promoting the status of the school in the community rather than active social change agendas’ (2016: 98). Andreotti (2006) found that in schools action is likely to be ‘soft’ rather than critical and that schools are more likely to engage in ‘The Three “Fs” of Fundraising, Fasting and Fun’ (Bryan and Bracken, 2011: 28). Doorly called them the ‘five “Fs” of food, fashion, festivals, flags and fundraising’ or actions such as signature gathering, wearing bracelets and debating, often linked to individual rather than collective action, which lacks power (2015: 116).

Science teacher Harry remembered his students protesting outside the Dáil about government cuts to development aid, against French nuclear testing in the South Pacific, against the Irish Rugby Football Union for playing rugby against South Africa during apartheid. This was all in the past. ‘But nowadays I don’t see students in protests. I’m not aware of any of our students going to protest anywhere’. Eamon felt that perceived parental pressure is the reason that teachers and students don’t get involved in more radical action. They say:

“Oh I don’t want her going to the inner city. I don’t want her giving soup to the homeless. We’re giving the money. We’re doing our part. Let someone else do that”.

He fears a lawsuit should anything go wrong. “A lot of that does come down unfortunately to litigation. If somebody hits a student when they’re out helping someone it’s ‘Oh I’m gonna sue’”.

Harry made a similar point:

“I probably don’t feel as free as I used to feel about saying to students ‘Do you want to get involved in this protest?’ I’d be more careful these days. The parents might have very different views on something. So I wouldn’t invite students to go on a march against the banks or something like that. Some of the parents could be big bankers”.

Bryan and Bracken had also found that, while teachers were not opposed to the notion of students becoming politically engaged, most were reluctant to explicitly encourage the political ‘mobilization’ of students (2011: 26). They were concerned that political actions might provoke negative consequences or sanctions from parents or the wider community. Tallon et al. (2016) questioned the narrow focus of DE and wondered what kinds of global citizens are we encouraging in our schools if this is how we perceive DE. ‘Action may be packaged up to avoid the difficult questions and continue the systems that paper over the cracks’ (ibid: 107). Charity and ‘soft’ actions are acceptable but anything more radical that questions the status quo is not. This resonates with the findings of Flannery who questioned ‘all their rhetoric and endeavours in the area of justice and equality’ (2016: 21) and asked ‘how in our schools are we preparing our students to be active agents for transformative political, social and economic change?’ (ibid).

Global education and the Irish examination system

Bryan highlighted an inherent tension between the goal of DE, which seeks to develop active citizens, and an education system which views the primary purpose of education as to ‘prepare students for competitive employment in the global marketplace’ (2011: 4). She alluded to the exam-driven focus of the curriculum as being a major obstacle to the meaningful inclusion of development issues and global justice themes in schools (ibid). O’Brien (2017) noted that the modern classroom resembles a military training ground where students are drilled to produce perfect answers to potential questions based on examiners’ marking schemes. This focus also deprives students of the opportunity to develop critical thinking skills. Some multinational employers and universities complain that too many school-leavers are emerging from an exam-obsessed second-level where students are ‘taught to the test’ and are not learning to think for themselves (ibid).

Conclusion

I have found that the principles of GE are compatible with the stated Catholic ethos of Irish Secondary schools. I have also found that this ethos remains largely aspirational in these schools and that in reality they do not espouse real and radical social change. Despite the idealistic rhetoric of mission statements, the most influential values in such schools are consumerist as students compete for places on high-points university courses as these qualifications will lead to highly paid careers, status and wealth. The ability to think critically is not a skill necessary to achieve high points in Leaving Cert examinations; so, unfortunately, this is not prioritised at senior level in our schools. Junior Cycle reform has meant that the ability to think critically is now a requirement of the Junior Cycle (DES, 2015). Reform of the Senior Cycle is planned but, while the points system continues to be utilised for selection for college places, it is unlikely that significant change will happen soon.

This disconnect with their stated ethos poses significant challenges for the successful implementation of GE within the schools. A great opportunity exists, however, for GE practitioners to work with school management, to highlight the link between school ethos and GE, to analyse the school mission statements and to see how implementing a solid GE programme could help schools live out their ethos. A good GE programme could embed a social justice perspective across all subject areas to avoid infringing on examination preparation. Ideally, action for justice could move beyond fundraising but otherwise fundraising and immersion trips could be accompanied by intense analysis as to why these activities are considered necessary. Global education can help schools to move beyond the rhetoric to become real promoters of social justice and to inspire their students to become agents of change.

References

Andreotti, V (2006) ‘Soft versus Critical Global Citizenship’ in Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 3, Autumn, pp. 40–51, available: https://www. developmenteducationreview.com/issue/issue-3/soft-versus-critical-global-citizenship-education (accessed 02 March 2017).

Bourn, D (2016) ‘Teachers as Agents of Social Change’, International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 63-77, available: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1475774/1/5.%20Bourn_Teachers%20as%20agents%5... (accessed 18 July 2018).

Bryan, A (2011) ‘Another Cog in the Anti-Politics Machine? The “De-clawing” of Development Education’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 12, Spring, pp. 1-14, available: https://www.developmenteducationreview.com/issue/issue-12/another-cog-an... (accessed 23 August 2018)

Bryan, A and Bracken, M (2011) Learning to Read the World? Teaching and Learning about International Development and Global Citizenship in Post-Primary Schools, Dublin: Irish Aid.

Central Statistics Office (CSO) (2018) ‘Second Level Schools and Pupils by Type of School, Statistical Indicator and Year’, available: https://www.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/saveselections.asp (accessed 18 July 2018).

Cleary, B (2015) Education for Transformation through Gospel Values, Dublin: Des Places Educational Association.

Comhlámh (2017) The Comhlámh Code of Good Practice, available: http://comhlamh.org/code-of-good-practice/ (accessed 18 July 2018).

Department of Education and Skills (DES) (2015) Framework for Junior Cycle 2015, available: https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Policy-Reports/Framework-for-Ju... (accessed 19 July 2018).

Department of Education and Skills (DES) (2016) Politics and Society Curriculum Specification, available: https://www.curriculumonline.ie/getmedia/e2a7eb28-ae06-4e52-97f8-d5c8fee... (accessed 02 August 2018).

Dillon, E (2016) ‘Development Education in Third Level Education-What is Development Education?’ in M Cenker, L Hadjivasiliou, P Marren and N Rooney (eds.) Development Education in Theory and Practice – An Educator’s Resource , pp.11 – 44, Cyprus: UNIDEV NGO Support Centre, Slovakia: Pontis Foundation, Ireland: Kimmage Development Studies Centre.

Doggett, B, Grummell, B and Rickard, A (2016) ‘Opportunities and Obstacles: How School Leaders View Development Education in Irish Post-Primary Schools’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 23, Autumn, available: https://www.developmenteducationreview.com/issue/issue-23/opportunities-and-obstacles-how-school-leaders-view-development-education-irish-post (accessed 18 April 2017).

Doorly, M (2015) ‘The Development Education Sector in Ireland a Decade on from the Kenny Report: Time to Finish the Job?’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 20, Spring, pp. 114-122, available: https://www.developmenteducationreview.com/issue/issue-20/development-education-sector-ireland-decade-%E2%80%98kenny-report%E2%80%99-time-finish-job (accessed 23 August 2018)

EWGEC (Europe Wide Global Education Congress) (2002) The Maastricht Global Education Declaration, available: https://rm.coe.int/168070e540 (accessed 18 July 2018).

Fiedler, M, Bryan, A. and Bracken, M (2011) Mapping the Past, Charting the Future: A Review of the Irish Government’s Engagement with Development Education and a Meta-Analysis of Development Education Research in Ireland’, Dublin: Irish Aid, available: https://www.ideaonline.ie/uploads/files/Mapping_the_Past_Fiedler_Bryan_Bracken_2011.pdf (accessed 31 July 2018).

Flannery, B (2016) ‘Reflections from an Ignatian Educational Perspective’, Working Notes Affairs, Vol. 79, pp. 21-26, December,available: http://www.workingnotes.ie/item/reflections-from-an-ignatian-educational-perspective (accessed 18 July 2018).

Freire, P (1996) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, London: Penguin.

Freyne, P (2013) ‘Are School Fees Fair?’, The Irish Times, 31 August, available: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/education/are-school-fees-fair-1.1510916 (accessed 18 July 2018).

Gleeson, J, King, P, O’Driscoll, S and Tormey, R (2007) Development Education in Irish Post-Primary Schools: Knowledge, Attitudes and Activism, Dublin: Irish Aid, available: http://www.ubuntu.ie/media/report-2007-gleeson.pdf (accessed 19 July 2018).

Godwin, N (1997) ‘Education for Development: A Framework for Global Citizenship’, The Development Education Journal, Vol 7, No. 1, pp. 15–18.

Honan, A (2006) A Study of the Opportunities for Development Education at Senior Cycle, Dublin: Irish Aid/NCCA, available: http://www.ubuntu.ie/media/deved-senior-cycle.pdf (accessed 19 July 2018).

IDEA (2013) Good Practice Guidelines for Development Education in Schools, available: https://www.ideaonline.ie/pdfs/IDEA-Good-Practice-Schools-Full-Report_14... (accessed 19 July 2018).

Jefferess, D (2008) ‘Global Citizenship and the Cultural Politics of Benevolence’, Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices, Vol 2, No 1, pp. 27–36.

Jeffers, G (2008) ‘Some Challenges for Citizenship Education in the Republic of Ireland’, in G Jeffers and U O’Connor (eds), Education for Citizenship and Diversity in Irish Contexts, Dublin: The Institute of Public Administration, available: http://eprints.maynoothuniversity.ie/2812/1/GJ_Chapter.pdf (accessed 19 July 2018).

Kruesmann, M (2015) Challenge and Change: Global Citizenship Education in UK Schools, London: Think Global, available: https://think-global.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2016/01/Symposium... (accessed 19 July 2018).

McCloskey, S (2016) ‘Are we Changing the World? Development Education, Activism and Social Change’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 22, Spring, pp. 110-130, available: https://www.developmenteducationreview.com/issue/issue-22/are-we-changin... (accessed 23 August 2018)

NCCA (n.d.) Politics and Society, available: https://www.ncca.ie/en/senior-cycle/curriculum-developments/subjects-and-frameworks-in-development/politics-and-society (accessed 02 August 2018).

NCCA (2017) Junior Cycle Wellbeing Guidelines, available: https://www.ncca.ie/media/2487/wellbeingguidelines_forjunior_cycle.pdf (accessed 02 August 2018).

O’Brien, C (2017) ‘Is our education system fit for purpose in the 21st-century?’, The Irish Times, 17 April, available: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/education/is-our-education-system-fit-fo... (accessed 22 April 2017).

Rickard, A, GrummellB and Doggett, B (2013) WorldWise Global Schools: Baseline Research Consultancy, Dublin: WWGS.

Simpson, J (2017) ‘“Learning to Unlearn’” the Charity Mentality within Schools’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 25, Autumn, pp. 88-108, available: https://www.developmenteducationreview.com/issue/issue-25/%E2%80%98learning-unlearn%E2%80%99-charity-mentality-within-schools (accessed 31 July 2018).

Tallon, R, Milligan, A and Wood, B (2016) ‘Moving beyond fundraising and into … what? Youth Transitions into Higher Education and Citizenship Identity Formation’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 22, Spring, pp. 96-109, available: https://www.developmenteducationreview.com/issue/issue-22/moving-beyond-... (accessed 18 July 2018).

Tormey, R (2008) ‘Development Education: Debates and Dialogues’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 7, Autumn, pp. 109-111, available: https://www.developmenteducationreview.com/issue/issue-7/development-edu... (accessed 18 July 2018).

Anne Payne is a secondary school teacher who is currently seconded to the Irish Aid Development Education Unit. As Education Officer in Irish Aid, she liaises with organisations who deliver development education in Irish post-primary schools. She recently completed a Masters in International Development in Kimmage Development Studies Centre, Dublin and is particularly interested in global education/development education at post-primary level.