Opening Eyes and Minds: Inspiring, Educating and Engaging Third Level Students in Global Education

Finding the 'Historically Possible': Contexts, Limits and Possibilities in Development Education

Abstract: Suas has worked since its inception to engage Irish third level students in global citizenship education. This article focuses on the Suas Global Citizenship Programme, setting out the purpose and context of the programme, its innovative design and educational approach and its comprehensive monitoring and evaluation framework. The article presents an analysis of key findings from Suas’ evaluation process and a summary of our learning to date on the challenges of supporting third level students in reflecting, learning and acting on global justice issues.

Key words: Global Citizenship; Higher Education; Tertiary Education; Global Campus; Monitoring and Evaluation.

“It was the most challenging yet rewarding thing I've ever done. The way I feel now is that I can take up any task which perhaps before the Suas experience I would have thought too difficult for myself. Despite exposure to the harsh reality of the living circumstances of most Kolkata citizens, I feel more positive about life in general and my ability to change the world in a positive manner” (Participant, Suas Overseas Volunteer Programme, 2013).

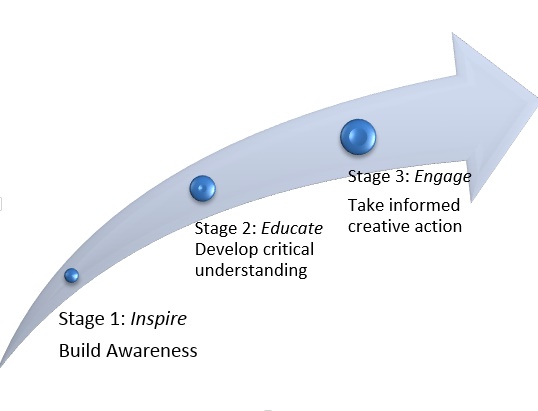

Founded by students for students in 2002, Suas has worked since its inception to address educational disadvantage in Ireland and abroad. Suas, a charitable organisation based in Dublin, achieves this through working with partner organisations to develop and deliver education programmes for young children in Ireland and the global South; engaging and preparing volunteers to support programme delivery; and building a wider movement of members who share the Suas vision and aims. Global citizenship education (GCE) constitutes a core part of Suas’ work. Suas’ Global Citizenship Programme initially emerged from its flagship Overseas Volunteer Programme (OVP), as returning volunteers founded local student societies and began a range of volunteering and awareness-raising activities in Ireland. Fundamentally, the programme seeks to support the progressive engagement of third level students with global justice issues through an integrated programme of activities that correspond to different ‘stages’ of participation and learning.

Figure 1. Three stages of the Global Citizenship Programme

Since 2002 the Global Citizenship Programme has grown significantly, focusing on five university locations in Ireland – Dublin City University, National University of Ireland Galway, Trinity College Dublin, University College Cork and University College Dublin. In 2010, Suas joined with three European partner organisations – Suedwind Agentur (Austria), the Centre for the Advancement of Research and Development in Educational Technology (CARDET, Cyprus), and KOPIN (Malta) to extend the Global Citizenship Programme into a further eight university locations across Europe using the name ‘Global Campus’. In addition to their work with third level students, Suas and partners undertake various development, networking, capacity building and communications activities to promote and sustain non-formal GCE in the third level education sector.

This article focuses on the Global Citizenship Programme in Ireland, setting out the purpose and context of the programme, its innovative design and educational approach and its comprehensive monitoring and evaluation framework. The article concludes with an analysis of key findings from Suas’ evaluation methods and a summary of our learning to date on the process of engaging third level students in GCE.

Context and purpose of the Global Citizenship Programme

Suas’ Global Citizenship Programme is underpinned by a theory of change that is based on two main assumptions: firstly, that the critical engagement and action of Irish citizens is essential in overcoming global development challenges such as poverty, disease, pollution, climate change, inequality; and secondly, that GCE plays a key role in building that active and critical engagement by equipping people with the skills, knowledge, and attitudes to critically engage with global issues and effect change for a more just and equal world. Since its foundation by a group of third level students in the Trinity College Dublin St. Vincent de Paul Society in 2002, Suas has consistently encountered considerable student interest in global justice issues. However, a 2011 thematic review of development education in Ireland, carried out by Irish Aid, showed that less than one percent of 160,000 full-time, third level students participated in Irish Aid funded development education courses (Irish Aid, 2011: 11). This prompted a root and branch analysis of Suas’ experiences to date and an examination of the challenges and opportunities at third level for advancing a more critical engagement with global justice issues.

To gain a better understanding of students’ attitudes, knowledge, understanding, activism and learning on global development, Suas commissioned a National Survey of Third Level Students on Global Development in 2012. The National Survey results were extremely encouraging, indicating a strong student interest in global development and justice issues and a positive attitude towards taking action for a more just world (2013: 12). However, the overall student response to the survey highlighted the following challenges:

- Significantly more work was needed to build student motivation and increase student commitment to take action on global justice issues;

- Education providers needed to explore how students could make a positive impact on development issues and draw attention to the different ways in which students’ skills could be put to good use;

- Interventions needed to build students’ critical understanding of global issues and engage students in both individual and collective forms of action that together seek to address not only the symptoms of poverty and inequality but also the structural causes;

- GCE activities needed to expand to include online learning opportunities. They also needed to be promoted more effectively on campus and through social media.

Programme design

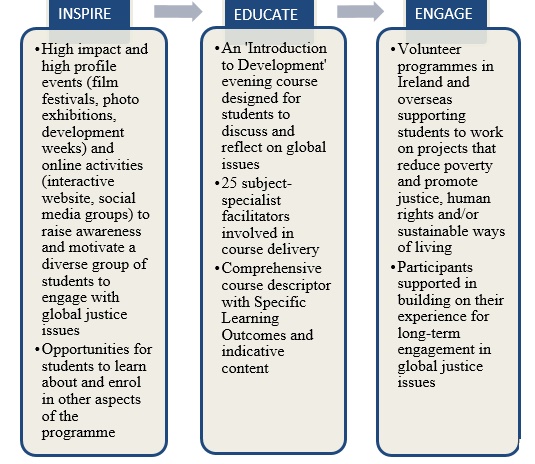

In responding to these challenges, Suas and its European partners perceived significant challenges in meaningfully integrating GCE within the formal curriculum. However, the potential of the non-formal space at third level was noted and an integrated, multi-component, non-formal programme was designed to cater to students’ interests, needs and availability. The programme combined existing ‘tried and tested’ Suas activities (courses and volunteering projects) with new activities (large-scale awareness raising and online activities) within the following framework.

Figure 2. Global Citizenship Programme activities

The design and delivery of the Global Citizenship Programme has been heavily informed by the original Suas programme - the Overseas Volunteer Programme (OVP) – as well as our European partners’ experience of delivering GCE in Austria, Cyprus and Malta. The first key lesson from the OVP has been the critical importance of university stakeholder involvement in engaging students in GCE. Suas maintains strong links with student-based groups in higher education institutions, particularly Suas Societies which are run by interested students including returned volunteers. Suas staff members work directly with society committee officers and members to deliver GCE activities in their locations, with society officers often taking on key organisational roles. A campus coordinator on the 2014 Global Citizenship Programme remarked:

“I spoke to a large number of students who wanted to know more about the festival, and immediately signed up. Many of these students, after the various showings, asked whether there were any courses, volunteering opportunities or resources available.”

Suas has also maintained links with university staff throughout its existence. Individual staff members have supported Suas activities on campus in an advisory and/or practical capacity. With the development and expansion of the Global Citizenship Programme, Suas extended its stakeholder engagement with university bodies, for example, civic engagement offices, student unions and development bodies. Building on the relationships established by the OVP, Suas set up Global Citizenship Programme advisory groups and working groups on campus to bring key stakeholders together and provide a forum for discussion and working together.

A second lesson from the OVP relates to how the activities are promoted to maximise student participation. Suas particularly seeks to engage the ‘interested majority’ in our programme i.e. students from a wide range of disciplines who are not formally studying development but are interested and want to engage. To promote GCE activities, Suas connects with university students and staff across a range of disciplines and through a range of channels, notably word-of-mouth, social media, staff and student emails and campus media. We have come to understand that students have different interests and needs, and are more available, at different stages in their university life and may be better placed to engage with certain activities at certain times.

The final lesson from the OVP relates to its commitment to sustained engagement. It is extremely important that participants are supported and encouraged to continue their role as active, engaged, critical global citizens. By providing as much information as possible on the objectives and content of the activities and asking students to ‘apply’ or ‘register’ in advance, Suas encourages students to self-select for activities and take responsibility for their learning. Applicants for the OVP go through an extensive recruitment process consisting of individual interviews, group interviews and Garda (police) vetting given the involvement of children and young people in the projects and the potential mental, emotional and physical impact of placements. Suas believes that a comprehensive application process increases volunteer ‘buy-in’ and commitment and is rewarded with low drop-out rates and long-term commitments from participants. To sustain engagement, information and opportunities are provided to volunteers upon their return. It also encourages previous participants to reengage directly with Suas as programme supporters, organisers and/or facilitators – an accessible next step for returned volunteers with the potential to act as a catalyst for other actions. Katie, a student at the National University of Ireland at Galway (NUIG) said:

“The first time I was ever involved in or heard of Suas was through the Global Issues Course, which I took when I was in first year at college. I’m quite surprised at how big an impact the course has had on my life since then! ... A year later I was accepted on the Suas Volunteer Programme 2013 in Kolkata. I really can’t put the whole experience into words except to say it was definitely the single best decision I have made to apply. I feel as though I gained at least three years’ worth of life experience in three months. I met amazing inspiring people from India and Ireland. Most importantly it has made me realise what is important to me, how I want to live and what I want to achieve in the future.”

In autumn 2014 Katie will act as a Global Issues Course coordinator at NUIG thus deepening and sustaining her involvement with Suas’ on-campus programmes.

Education approach

Social justice theories of development are at the centre of all educational interventions in the Global Citizenship Programme. Particular attention has been paid to ensure that learners engage in a critical and transformative learning experience which actively challenges ethnocentric and modernisation understandings of development. This programme seeks to promote ‘critical’ global citizenship amongst participants by facilitating reflexivity, dialogue and reflection on one’s own assumptions, attitudes and privileges within a globalised world. The programme also seeks to instil a deeper understanding of the rights and duties of global citizens alongside an ethical and moral obligation to take action.

The programme acknowledges the opportunities advanced by the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) framework to engage students with the multiple and interconnected dimensions of poverty and inequality in the global South. However, it endorses the view of Bernardino (2002) that while the MDGs are ‘good themes’ which represent a ‘general global consensus’ on what is needed to eradicate poverty and achieve a more just world, there is a strong imperative to:

“formulate our education program and campaign on a critical understanding of the MDGs’ policy framework and put forward the need for flexibility in adapting paradigms for development that are not dogmatic but more attuned to the experience and needs of many developing countries” (Bernardino, 2002: 40).

Thus, the programme sees the MDGs as a springboard for participants’ critical engagement with global issues, international development policies and interventions. Programme activities seek to take the MDG discourse beyond 2015, addressing the gaps and shortfalls identified in the MDG framework and responding to new challenges and opportunities created by more recent events including inter alia, the impact of technological advances, the effects of the global financial crisis, the consequences of climate change, and the aftermaths of rapidly shifting political landscapes.

This programme conceptualises GCE as an enhancement of key life skills in a complex and increasingly interconnected world, an approach that relates personal and local life to global issues, focuses on the learning process, and actively supports critical thinking, self-reflection, civic engagement and independent decision-making skills in the learner. GCE here aims to develop competencies needed to lead a fulfilling life in a complex and globalised world and equip students with the competencies needed to participate in change processes from local community to global levels (DEEEP, 2010: 7). However, the programme also seeks to embed elements of a more radical form of global education in that it highlights the need for collective as well as individual action and structural change as well as lifestyle change. The programme acknowledges the relatively privileged setting of third level education in which global citizenship is being carried out, and takes on board Spivak’s (2004) warning that to avoid projecting and reproducing ‘ethnocentric and developmentalist mythologies onto Third World subalterns’ educational interventions should emphasise ‘unlearning’ and ‘learning to learn from below’. There is a need to facilitate participants’ ability to challenge ethnocentric assumptions and dominant representations of global issues and connect with much deeper narratives. The project therefore draws on Andreotti’s concept of critical literacy which advocates:

“providing the space for [learners] to reflect on their context and their own and others’ epistemological and ontological assumptions: how we came to think/be/feel/act the way we do and the implications of our systems of belief in local/global terms in relation to power, social relationships and the distribution of labour and resources” (2006: 49).

The teaching approaches that are considered by this programme to be most appropriate for enhancing critical literacy skills are: participatory; creative; active; exploratory and inquiry-based; discursive/dialogue based; collaborative; solution-focused; issue-based/authentic. Consequently, the pedagogical approach in this programme requires educators to abandon traditional ‘top-down’ teaching methods in favour of collaborative, democratic approaches to student learning.

Monitoring and evaluating the Global Citizenship Programme

Mapping changes in knowledge, skills, attitudes and in the propensity to take action can be a challenging process given that many small interventions may need to take place before a tipping point is reached and observable change occurs. Moreover, outcomes for educational programmes such as the Global Citizenship Programme can often occur in a non-linear, multi-level, multi-dimensional and non-sequential fashion (Bamber, Owens, Schonfeld, & Ghate, 2009). This makes it difficult (although not impossible) to document how specific interventions can lead to specified outcomes. A considerable amount of time and effort was invested by Suas to ensure that all activities stem from a robust results-based framework which sets out realistic indicators for short-term and long-term outcomes.

It was essential to put in place a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation process to capture credible data on the reach and impact of programme activities. Both qualitative and quantitative methods are used in the approach, and our evaluation framework maps indicators to specific research methods. The programme has worked with partners and external evaluators to refine the methods used for tracking changes in the awareness, critical understanding and informed, constructive action for development of students and other key stakeholders in the thirteen university locations in which the programme is delivered. This section of the article illustrates key findings from monitoring and evaluating the Inspire and Educate aspects of the Global Citizenship Programme.

Inspire

The purpose of the Inspire activities is to raise awareness of global justice issues and encourage students to deepen their understanding. Activities are designed to be engaging, interesting and thought-provoking and, within this context, Suas organised a global film festival in five campuses in 2013. This type of event, by its nature, does not lend itself to formal evaluation of what students have ‘learned’ or gained from attending; rather, it is intended as a first step to draw people in, raise awareness and deepen understanding, and provide opportunities for deeper engagement.

As a consequence, the evaluation process focuses on numbers of students reached and includes information on gender breakdown and fields of study. A snap survey is also carried out with Inspire participants immediately after activities to assess the impact and effectiveness of the event. For example, an Inspire participant in 2013 said of the activities:

“A great festival that is available to everyone, with a variety of subjects and topics so everyone will find something that interests them...without the 8x8 film festival I might never have been exposed to this subject. I also found that the documentary screenings humanized issues that we hear about on the news and in the media every day. It put a face and a human story behind figures and facts that so often just pass over our heads.”

A survey is carried out with participants after approximately six months to assess the effectiveness of the event in acting as a catalyst for further engagement with global issues. Suas also invests in online activities that aim to complement and build on Inspire activities. For online engagement, Suas tracks the nature of engagement ranging from signing up to the online network (www.stand.ie), accessing the website/newsletter, and joining social media groups to engaging more proactively in the network, for example, by posting on the website or social media and initiating/having conversations on global justice issues. The stand.ie website has had a readership of over 2,700 in the first six months of 2014 of whom 40 percent are returning visitors, while the website continues to attract new readership and followers as well as new student authors and editorial committee members.

Educate

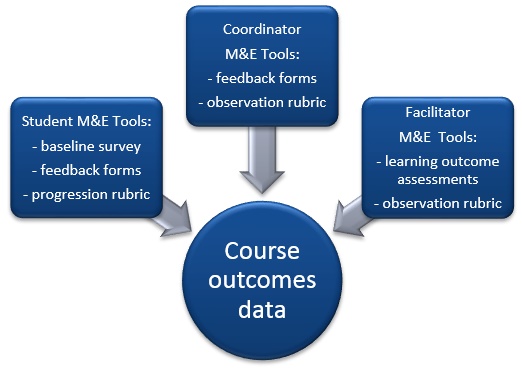

To monitor and evaluate the seven-week Introduction to Development course, the programme adopts a mixed method, triangulation approach with students, facilitators and course coordinators all reporting qualitatively and quantitatively on the perceived impact of the course. The resulting sets of data are combined and analysed to assess the effectiveness of the programme in delivering short term and long term outcomes. A number of evaluation tools have been designed specifically to collect data on each of the indicators.

Figure 3. Course monitoring and evaluation tools

The evaluation tools take into account the non-formal nature of the evening course and its relatively short duration and were designed to allow creative and practical means of collecting data. Learning outcome assessments and observation rubrics use teaching and learning activities such as debates, simulation games, role plays and quizzes to indicate students’ knowledge and skill in relation to core outcomes. Working with course coordinators, experienced facilitators assess student progress over the course across a range of specified indicators, including the ability to identify complex relationships between local and global issues and the ability to reflect on one’s own position in a globalised world. The tools are designed to capture facilitator feedback in a systematic and standardised format. Although these tools are unable to capture nuanced and complex information, they provide an accurate and objective snapshot of student progress in a systematic and standardised format. Used in conjunction with a primary evaluation tools such as pre- and post-intervention surveys and qualitative interviews with focus groups and individual participants, the data provides a comprehensive picture of programme impact.

Suas is very interested in student pathways to engagement with global justice issues and to this end the Global Citizenship Programme tracks the number of participants who progress through the three strands of the programme – from Inspire to Educate to Engage activities. Suas also follows up with a proportion of alumni online to ascertain other actions they have taken on foot of their involvement in global citizenship. A new tool, a progression pathway rubric, was introduced by Suas in autumn 2013. The rubric is completed by participants at the end of the global learning course and is designed to support students to reflect on the different opportunities for continuous engagement and what they would like to do as a result of their participation on the course. It suggests a series of seven general action pathways and tracks participants’ inclination to engage with each pathway as a result of their participation. The pathway is not intended to compel participants into particular actions; participants are free to opt out of further engagement and/or suggest their own action pathway. However it does provide concrete suggestions and enables Suas to provide tailored support to students wishing to go further.

Learning

Even at this early stage of the Global Citizenship Programme, the first year of delivery has been a steep learning curve for Suas and the team would like to share some of the lessons learnt. Firstly, there is a strong student demand for global citizenship education and providing a mix of activities that cater to students’ different interests, needs and availability. The programme has enabled students to progress from one activity to another and achieved positive and encouraging results. In 2013Inspire activities, such as the film festival, attracted 2,684 student participants, Educate activities had 309 participants (an increase of 28 percent on 2012) and Engageactivities had 91 participants, the highest since 2009.

Secondly, there is significant support for these activities within the third level sector in Ireland and in Austria, Cyprus and Malta where our partners are working. This type of programme benefits from the renewed focus on the purpose of third level education and the desire to produce graduates who are ‘globally engaged citizens’ with associated knowledge and skills. This high level of support translated into the involvement of forty-nine university staff and eighteen student societies/groups in the organisation and delivery of the film festival alone in 2013. Liaising with this number of external supporters created a significant demand for Suas resources; however the success of the event would not have been possible without their involvement.

A third and particularly encouraging finding for the Suas team has been the significant changes in knowledge, skills and attitudes amongst participants. Students emerge with a deeper and more critical understanding of the issues following their engagement with the Global Citizenship Programme. Learning outcome assessments completed by facilitators provided evidence that 88 percent of participants had a deeper understanding of the internal and external causes of poverty, a finding strongly supported by qualitative research and post-course surveys carried out with the students themselves. For example, an Educate participant in 2012 said:

“Our beliefs and what we thought we knew was also challenged, because what you thought you knew wasn’t true at all. Your perspectives and your beliefs were being challenged because what you might have thought wasn’t an issue, well, the facts were there for you and you had to re-think it.”

Interestingly, there is evidence that students participating in the Global Citizenship Programme are arriving with a greater understanding of the issues than was previously the case. This is something that requires further research and analysis in 2014 and 2015 but could well be an indication that ongoing interventions in GCE and development education at primary and secondary level are having a positive, cumulative effect on the knowledge and awareness of students.

In terms of sustained impact, evaluations show an increase of over 60 percent in the proportion of students motivated to take action on development issues after participation in the Global Citizenship Programme. An Educate participant in Spring 2014 said: ‘I feel like these issues are important to everyone but they don't know what to do or how to take actions, and this course can help you see how to do that.’ There also appears to be a correlation between depth of engagement and the level of activism/support with Inspire participants undertaking 2.4 actions on average, Educate participants undertaking 4.3 actions and Engage participants undertaking 6.7 actions (based on a list of thirteen possible actions). Actions varied for the different groups but the most common actions included making changes to lifestyle and consumer habits, engaging with global justice issues online, raising awareness and encouraging others to act on global issues and making charitable donations to global development causes.

At the same time, it is clear that there are limits to participation with competing demands on student time having a particularly negative effect. This is evident from the 25 percent reduction in the number attending the festival compared to the number registered and from the 151 students who withdrew after registering as participants on the Introduction to Development course. It has also proved difficult to recruit a full complement of participants for the long-term commitment of theEngage element of the programme. Time constraints could also explain the compensating increase in online engagement. This has underscored the importance of scheduling activities around student and staff availability and of developing online opportunities for engagement.

It is also clear that a robust and well-resourced monitoring and evaluation process is an essential part of the overall programme. As mentioned previously, measuring changes in knowledge, skills and attitudes in the non-formal learning sphere is a complex task requiring innovative and creative approaches to data collection. Adopting a mixed methods approach has been incredibly useful in producing a multi-layered, multi-faceted analysis of the programme and in providing in-depth information on the full impact of the programme activities. It has also helped unearth discrepancies between perceptions of learning from participants, facilitators and staff, hitherto masked by purely quantitative approaches to evaluation. The monitoring and evaluation process has also generated a reflexive approach to programme content and delivery with ongoing discussions about the impact of activities, the effectiveness of teaching and learning methods, the relevance of curricular content, and the successful achievement of learning outcomes. This in turn provides a strong platform for periodic, independent, in-depth reviews of the programme.

Designing and implementing a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation process was not without its difficulties. The introduction of evaluation tools for facilitators and coordinators into non-formal learning spaces proved challenging at first. Initially, there were concerns that these tools constituted a move towards a ‘standardised testing’ of students with facilitators and coordinators understandably worried about potentially negative implications for teaching and learning approaches. There were also concerns that in-class observations and assessments would ‘take over’ the learning process and divert time and resources away from the course content. A strong communications strategy was needed to reassure staff that the evaluation process was designed to allow a reflective practitioner model of evaluation rather than a narrow testing of students and that facilitators and coordinators would receive ongoing support in implementing the new tools.

It is also important to acknowledge the time, resources and expertise needed to establish and maintain an effective monitoring and evaluation process. As a medium sized organisation without dedicated staff for this purpose, the collection, analysis and reporting of data proves a challenge for Suas and would not be possible without adequate funding or the support of independent coordinators, facilitators and evaluators involved in the programme.

Conclusion

The experience of delivering the Global Citizenship Programme has been encouraging and convinced Suas and our partners of the continued relevance of GCE for third level students. We have also been struck by the interest and support for GCE among other third level education stakeholders such as academic staff, students unions, civic engagement offices and development bodies. The programme has highlighted the importance of responding to the perceptions, needs and interests of students and taking a flexible approach, which supports students to progressively engage with global justice issues. This student-centred approach remains relevant given the continuing impacts of the financial crisis on young people in Ireland. More third level students are now working part-time during their studies and are concerned about career opportunities upon graduation. Students are also influenced by increased public scrutiny of government expenditure and distrust of state-funded institutions including NGOs.

The process of designing, delivering and monitoring the programme has supported Suas and our partners to refine our educational approach and to better understand the specific changes in knowledge, skills and attitudes that are being achieved. Consequently, we are willing and able to share our experiences and learning with others working in the field of GCE, particularly in the third level education sector. We are still in the early stages of the programme and we will continue to share our learning; together with our European partners, we are developing a website (www.globalcampus.eu), programme resource and articles to communicate the approach, results and lessons learnt in delivering the Global Citizenship (‘Global Campus’) Programme.

References

Andreotti, V (2006) ‘Soft versus critical global citizenship education’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 3, Autumn, pp. 40-51.

Bamber, J, Owens, S, Schonfeld, H and Ghate, D (2009) ‘Effective community development programmes: An executive summary from a review of the international evidence’, Dublin: Centre for Effective Services.

Bernardino, N (2002) ‘Global education in Europe: Some Southern perspectives’ in E O’Loughlin and L Wegimont (eds.) Global Education in Europe to 2015: Strategies, policies and perspectives, available: http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/nscentre/Resources/Publications/GE_Maastricht_Nov2002.pdf (accessed 19 August 2014).

DEEEP (2010) European Development Education Monitoring Report, ‘DE Watch’ published by the European Multi-Stakeholder Group on Development Education, Brussels: DEEEP, available: file:///C:/Documents%20and%20Settings/Stephen/My%20Documents/Downloads/DE_Watch.pdf (accessed 19 August 2014).

Irish Aid (2011) Synthesis Paper: Thematic Reviews of Development Education within primary, post-primary, higher education, youth, adult and community sectors, [online], available: https://www.irishaid.ie/news-publications/publications/publicationsarchive/2011/july/synthesis-paper--thematic-reviews-of-development/ (accessed 19 August 2014).

Spivak, G (2004) ‘Righting wrongs’, The South Atlantic Quarterly, Vol. 103, pp. 523-581.

Suas (2013) Report on the National Survey of Third Level Students on Global Development, available:

https://www.suas.ie/sites/default/files/documents/Suas_National_Survey_2013.pdf (accessed 19 August 2014).

Joanne Malone is the Global Citizenship Programme Manager and has been working with Suas since 2009. Prior to that, Joanne worked as a project executive with Middlequarter Consultancy. With a background in languages, politics and administration, she has spent over seven years working in education and project management roles in Ireland, France and India. Joanne first got involved with Suas in 2004 while studying in Trinity College Dublin.

Gráinne Carley has been working on Suas’ Global Citizenship Programme since early 2014. Prior to that she worked for the CDETB Curriculum Development Unit coordinating the EU-funded Refugee Access Programme for Separated Children Seeking Asylum. She has spent more than ten years working in the field of education both at home and abroad.

Meliosa Bracken has over ten years’ experience in global citizenship education. She works as an educational research consultant with a particular interest in the monitoring and evaluation process. She has previously worked as a researcher in the School of Education, University College Dublin (UCD) and is currently the coordinator of a development education project for adult learners in South Dublin.