Education About, For, As Development

Development Education Without Borders

“The content of education which is subject to great historical variation... expresses certain basic elements in a culture... being in fact a selection, a particular set of emphases and omissions” (Williams, 1961: 145).

Introduction

Development and development education need to be more linked and learn from each other (Bourn, 2012). The differences in standards of living between Northern and Southern parts of the globe are stark with some geographical regions requiring development education to recognise their over-development and negative impact on global resources (Orr, 1991), while others have development needs that urgently require the technological innovations and development that make Northern lives easier (Rosling, 2011). So how do local development needs especially in developing countries translate into development education? And in what ways does the inclusion of the local affect activism and mobilisation for development arising from the educational intervention? These questions draw on my experiences as a participant on the Advanced Development Education in Practice course organised by Development Perspectives in Ireland and DEN-L in Liberia, and on my lecturing work with the students of the Masters in Development Practice, Mary Immaculate College (MIC) Limerick. These experiences raised many questions for me regarding the purpose of development education, the expectation of activism and change-orientated agency arising from development education interventions, and the inclusion of local and global development content.

In this paper I wish to focus on the relationship between development and development education, in particular focusing on the form development education may take in developing country contexts. I examine how national settings and local development concerns influence the type and content of development education programmes. To consider this question, I called on the tripartite explanations of development education as education about, for and as. Tormey summarises the three types saying that development education includes:

“[E]education as personal development, facilitating the development of critical thinking skills, analytical skills, emphatic capacity and the ability to be an effective person who can take action to achieve desired development outcomes. It is education for local, national and global development, encouraging learners in developing a sense that they can play a role in working for (or against) social justice and development issues. It is education about development, focused on social justice, human rights, poverty and inequality, and on development issues locally, nationally, and internationally” (Tormey, 2003: 2).

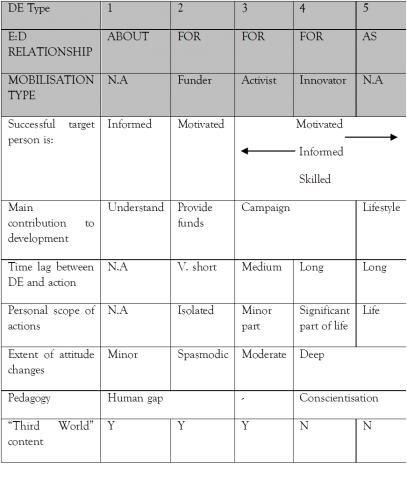

In this paper I present a table by Downs (1993) outlining five types of education about, for and as development; then I present an updated version of his table I prepared for my students in MIC earlier this year. All five types are in operation and his analysis differs to a historical or generational understanding which places some forms in the past (Mesa 2011). Andreotti’s (2006a) analysis of soft and critical forms of development education also informed my thinking and questioning, as I wondered what factors affect and lead to different forms, beyond the political orientation and critical literacy of the development education practitioner. Local development needs and national factors can be influential also.

Types of development education

Development education highlights the inequalities and injustices present across our globe, and advocates action for global social justice. It is defined by the Irish government as:

“...an educational process aimed at increasing awareness and understanding of the rapidly changing, interdependent and unequal world in which we live... It seeks to engage people in analysis, reflection and action for local and global citizenship and participation... It is about supporting people in understanding and acting to transform the social, cultural, political and economic structures which affect their lives at personal, community, national and international levels” (Irish Aid, 2006).

This official Irish government definition highlights many of the necessary aspects of development education: the educational content areas; the skills developed such as critical thinking; and the encouragement for action towards social change and transformation. Another way to consider the multiple forms of development education can take is through the lens of three types of education about, for and as development. The tripartite concept of education about, for and as has been usefully applied to environmental education (Fien 1991; 1993) and can also be applied to development education. The three stances reflect how the purpose and aims of education is envisioned, the form of content and knowledge, and the teaching and learning approach used. Despite being twenty years old, Downs’ table is applicable and informative today in considering different types of development education in operation. The three approaches are summarised in the table below.

Table 1. Summary characteristics of different types of DE (Downs, 1993)

About, For, As Development

The following section looks at these types of education in detail.

Education about development

Education about development is learning about the developing world; essentially facts and data on global inequalities, addressing issues such as poverty and hunger, gender and maternal health. This relates to education about Type 1 on Downs’ table (1993). This approach to global learning aims to develop a moral commitment to the concerns of the developing world and about global inequalities, but does not necessarily lead to a critical stance on the causes or the structures which maintain global poverty. Within this type of development education, immediate short-term learning outcomes can easily be defined and tested through increases in knowledge and awareness of global issues. However it is acknowledged that knowledge alone does not engender change or ethical maturity. A content-centred approach to education does not create critical or analytical capacity to question the embedded messages on global inequalities. As Wade (2006) argues, it is not the acquisition of knowledge that is important in development education; rather it is how this knowledge is put to use. Knowledge can be a dangerous thing when combined with values that negate life, justice, equality and sustainability. In Downs’ terminology mobilisation for development and action or activism arising from education about development is either not applicable or, more accurately, not expected. Certainly the action needed ‘to transform the social, cultural, political and economic structures which affect their lives at personal, community, national and international levels’ (Irish Aid, 2006) could not be expected from this type of educational intervention. In a similar way Krause (2010) questions whether this form of information based work can be classed as development education.

Furthermore, learning about global issues can raise overwhelming and far-reaching concerns, describing a world of ecological risk and economic uncertainty. Hicks (2006) argues that effective and engaged learning about global issues must address more than the cognitive dimensions; remaining in cognitive learning dimension could engender pessimism, hopelessness and cynicism rather than the engagement and empowerment necessary for addressing current and future challenges. While asking fundamental questions on our economies, politics and social choices, learners can be left without answers, feeling overwhelmed and possibly leading to cynicism about their capacity for change. However while this type may not be advocated by or used by many development education practitioners today, it must be acknowledged that this form of development education centring on information is one that is in use today particularly in formal education settings with a reliance on didactic teaching.

Education for development

Education for development centres on enhancing skills and capacity for societies and economies to develop. Downs’ table presents three forms of education for development – Types 2, 3, 4. Looking across these three forms, there is an evident progression towards more critical types of development education. Type 2 presents a form of education for development which builds on the knowledge provided by education about development to encourage action. Learners are aware, motivated and concerned about global development issues, however the impact on the learner is short-term and attitudinal change is spasmodic according to Downs, or occasional in my rephrasing. The primary mobilisation for development arising from this is fundraising. This charitable response is the only possible action which can be envisioned from this type of education for development, as without well-defined local connections the learner cannot implement change in their personal lifestyle. Clear links to modernisation theory could be made from the content of this approach. Downs’ work links here with Andreotti’s (2006a) analysis of soft and critical forms of development education as she argues that the critical literacy of the educator is central to more critical forms. However I believe the context of the work and the content is also an influencing factor.

Types 3 and 4 education for development promote more progressively critical approaches to education moving across Downs’ table. While the content is development centred, it could address local development concerns as much as global development issues seen in his row titled ‘Third World’ content. Types 3 and 4 education for development cultivate the skills of critical thinking and analysis centring on building the capacity of learners in development. Advocacy and campaigning for political and economic reform is identified as mobilisation for development resulting from these types of education. The emphasis within education for development types is on generating an understanding of a rapidly changing and interdependent world, and emphasising the learners’ role in that world.

In some interpretations, Type 3 education for development could be linked with vocational education with the emphasis on practical skills such as entrepreneurship. Science and technology are important to development, and development can occur through investment in research and new technologies. These are valuable skills in the developing world context and provide a vehicle for economic development, echoing human capital theory where the education system is seen as primarily of benefit to economic development. As Rosling (2011) eloquently demonstrates with his washline thesis, some modernisation is necessary for communities and women in particular to improve the quality of life and reduce hardship. However this type of development education does not necessarily lead to questioning the fundamental concerns regarding our economies or societies, and could centre on teaching the skills needed to perform in a globalised economy. This approach could be critiqued as being ideological as it could be linked to the modernisation thesis of economic progress (Rostow, 1960). This approach to education for development does not challenge the persistence of inequality, enhance participation in democracy or challenge cultural representations of the developing world. It does not necessarily challenge the structures of global trade that maintain inequalities and work to retain unfair advantages, nor necessarily ask fundamental questions about capitalism and economic systems.

The significant difference between Type 3 and 4 is the mobilisation for action arising from education for development, where Type 3 centres on campaigning and advocacy – titled activism by Downs – while Type 4 education for development includes lifestyle as their contribution to development – called innovator by Downs. This is where the impact of learning and the deep changes in attitude become more long-term and a significant part of one’s life – he uses the term conscientisation for Type 4. However in Downs’ work Type 4 education for development does not address global development issues as it refers to no ‘Third World’ content. I changed this to include both local and global content and thereby allow for more local-orientated development concerns and innovation for development. For example, I read Type 4 education for development as questioning Northern consumerist lifestyles and calling for personal innovation in consumption patterns as mobilisation for development. This change made clear the necessity of the inclusion of local development issues for more critical forms of development education, and for personal and social innovation to be the resulting actions.

Education as development

Education as development focuses on the potential social and personal development of the learner through engagement with global issues, called Type 5 by Downs. This type of development education centres on empowerment, participation and expansion of human capacities, sharing some outcome characteristics with active citizenship. Downs does not identify mobilisation for development resulting from education as development, saying this is not applicable. By this he could mean that learning is embedded in everyday life. However I believe he contradicts himself by labelling the learning arising as deep and naming both the personal scope of action and the long-term impact of the learning. Thus I reinterpret the mobilisation for development as long-term personal and social innovation. Attitudinal and lifestyle changes are expected as learning outcomes, which I label personal and social innovation and others could read as citizenship where awareness of global responsibilities is embedded in everyday behaviours and agency.

This type of education as development includes post-colonial theories and knowledge to highlight the global structures that maintain inequalities. These structures can be political and economic as well as knowledge centred – for example Mignolo argues that the South lack epistemic privilege in the creation of knowledge and argues for ‘epistemic delinking’ (2007: 458) and decolonising of knowledge, meaning a conceptual and theoretical delinking of social thought from Northern (in particular European) dominance. This allows for local interpretations of development to be included and for the content to be driven by their own development needs. It is an education process, where learners engage in constructive development of their knowledge of global issues and concepts in relationship with their local setting. Learning could be viewed as a dialogical process, echoing Freire’s (1970) concept of education through dialogue. In fact Downs here uses the Freirean term conscientisation for Types 4 and 5. By utilising these approaches in educational settings, learners’ capacities for critical and analytical thinking are enhanced.

This understanding of development education requires long-term engagement with development education concerns, and fulfils the call for development education to be ‘an educational process aimed at increasing awareness and understanding of the rapidly changing, interdependent and unequal world in which we live’ (Irish Aid, 2006). Furthermore it addresses the need for action to transform; however these innovations may be seen in the personal and social arenas rather than directed at political change. While Downs referred to no ‘Third World’ content, I also adapted this to include both local and global development issues and added post-colonial theories and post-development content to enhance the critical aspects of this type of education as development. This understanding also makes clear the overlaps with global citizenship education.

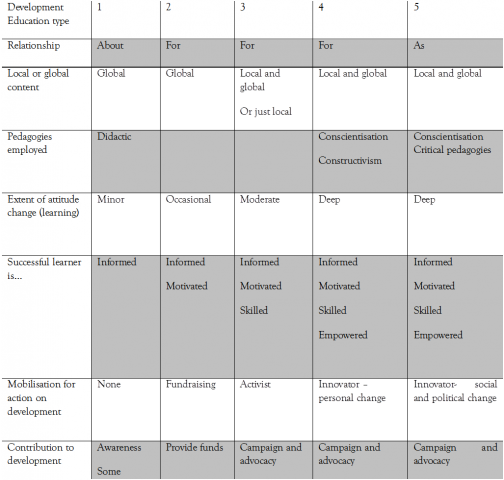

Summary of changes made

While Downs’ table is beneficial to illustrate the relationship between the three types of development education, I rewrote it for use on a module on development education which I teach as part of the Masters in Development Practice in Mary Immaculate College. During the Spring semester 2013 I distributed the two tables to the student group and we had meaningful discussions on its content and implications for their work in development, which in turn linked to the questions I had regarding the different forms development education can take and how national factors influence these forms.

Some of the language used in the row titles required updating as terminology has evolved over the past twenty years. For example, ‘Successful Target’ was changed to ‘Successful Learner’ and the ‘Pedagogy’ row was changed to ‘Pedagogies employed’ which is sub-titled ‘Extent of attitude change as learning’. I re-titled the ‘Local or global content’ row instead of ‘Third World’ content as I felt the inclusion of local development content demonstrated the necessity for local issues to be included in development education in order for lifestyle and personal change to occur. Additionally I added ‘Link to development theory’ and ‘Geographical focus of work’ rows to highlight the differences between the form development education can take in Northern and Southern settings.

Below is my adapted version.

Table 2. Summary characteristics of different types of DE (Liddy, 2013 adapted from Downs, 1993)

Arising from the rewriting and from discussions, there are three areas I would like to highlight in the discussion below.

Monitoring and evaluation

The first area I would like to highlight is the monitoring and evaluation implications arising from Downs’ work. The time lag between the development education intervention and action arising from it is identified by Downs, and his table highlights that the more engaged and critical forms of development education can lead to long-term changes. These changes in attitude (which I subtitle learning) are not immediately measurable nor can be pre-determined or defined as learning outcomes in the planning stages. This has implications for monitoring and evaluation work as the extent of attitudinal changes may not be seen by the conclusion of a learning programme or for a considerable time after the development education intervention.

The long-term changes in attitude arising from Type 4 education for development is titled innovator by Downs (1993) – this is an interesting aspect to learning arising from development education and has implications for the measurement of learning arising from development education. This innovator title I interpreted as personal changes for Type 4 education for development. This form of change-orientated agency places the centre of focus on personal lifestyle choices such as consumer behaviour, travel choices, reduction of resources use, analysis of impact, etc. While these are local and personal changes, they can have long-term global impacts by, for example, supporting fair trade products and a reduction in Co2 emissions. This innovation could lead to social and political transformation called for in the Irish Aid definition of development education – i.e. understanding and acting to transform the social, cultural, political and economic structures. The forms of learning and attitude change evoked in these types of development education, I believe, are contrary to the forms of monitoring and evaluation which measure immediate learning. They also conflict with predetermined learning outcomes rather than allowing for individual learning to be self-determined and evolve through the learning programme.

While these are important to note their implications are not of primary significance to the overall discussion in this paper. However the primary concern which I address in the following section is that Downs’ work builds an argument for the inclusion of local development issues as central to innovator learning and deep attitudinal changes. Downs demonstrates that more critical and engaged types of development education which impact most on the learner and create the most significant long-term attitudinal change arise from the inclusion of less global content.

National variations of development education

Downs’ original and my adapted table clarified my thinking on the form development education takes in different national and socio-economic contexts. Global orientated development education is the type we are most familiar with in Ireland, bringing about more awareness and understanding of the developing world and our interdependencies. Questions are asked on development policies and agendas with a global dimension bringing issues that may seem to be far away closer to us in the North. Initially from the Downs’ table, I was still unsure as to how Type 4 education for development without ‘Third World’ content is development education and not community development. However his argument became clearer when I further added the ‘Link to development theory’ and ‘Geographical focus of work’ rows which brought the global focus to the fore.

The inclusion of these new rows highlighted the differences between the Northern and Southern focus of development education work, and clarified for me the form that development education can take in developing world and Southern contexts. To give an example, DEN-L in Liberia provide development education focusing on local development concerns such as gender issues in their community, conflict resolution and the effects of climate change and deforestation on their land. But for development education to meet expectations of global content, Liberians should learn about Ireland, European Union, the Group of 8 leading industrialised countries (G8) etc. The question is why should Liberian development education programmes include global content? Their concerns are at local and national levels – they need to enhance education provision, literacy, develop skills such as entrepreneurship and innovation. They need the Type 3 education for the development skillset described earlier based on technological improvement to address local need. Many are living below Rosling’s washline where 61 percent of the Liberian population have access to an improved water supply and where Gross National Income is just $370 (World Bank, 2012). Also in Liberia, Type 4 education for development could address local development issues such as gender and democratic political participation and not necessarily require any global content.

However I believe learning about these topics from a global perspective brings a vital critical perspective by addressing the role of global institutions and systems which affect Liberia. The economic and social development of Liberia as a country is greatly impacted by global influences; the impact of Chinese investment (Alden, 2005) or the impact of large scale plantations such as the Firestone rubber plantation (Church, 1969). Liberia is also unfortunately very well known for war and conflict, and ensuing actions with the International Criminal Court are worthy of study (Akande, 2003). The inclusion of more critical theoretical accounts of globalisation and questioning of development agendas can enhance learners’ understanding of the global impact on their local context. Additionally without the inclusion of global issues, more critical questions on development as a project cannot be asked in their national context as well as internationally, and Type 5 education as development brings the focus on to power asking where the global power dimension is. This is the type of development education that DEN-L provides in Liberia bringing a global perspective and dimension to their programmes while working to address local development concerns and generate change in livelihoods and communities.

The ‘Local or global content’, ‘Link to development theory’ and ‘Geographical focus of work’ rows led to identifying a clearer difference between education for development and education as development – this difference centres on the local and global focus of the development education intervention, determines the content of the course provided and allows for transformation of the social, cultural, political and economic structures. This was the main question I had about development education in developing country contexts.

In 2010, I travelled to Liberia believing that Northern and Southern perspectives on development education are very different – now I believe this is far more nuanced than a simple clear-cut difference. Now I see how Southern local orientated development education shares much similarity with Northern local orientated community development; however Southern global orientated development education differs to Northern global orientated development education. Northern global development education addresses the omission of the developing world, while Southern development education focuses on the inclusion of global politics into local development concerns. This understanding celebrates the different types of development education and underscores the need for multiple forms of development education with differing content foci as all types of development education are necessary in different national and development contexts. However the mix of local and global content in development education brings me to my next point.

The paradox of critical development education needs to be less global and more local

Downs’ table shows how information about the world is not enough for personal innovation and social change as some types of education for development could only engender fundraising activities as mobilisation for development or could be modernisation and technology focused. These forms do necessarily address structural causes or analysis of global poverty and inequalities. More critical and informed innovation requires the inclusion of local orientated content to provide the opportunity for innovation on a personal and social dimension and for education as development to become embedded as a way of life. Including the ‘Link to development theory’ and ‘Geographical focus of work’ rows made clearer the paradox that critical development education needs to be less global and more local. This type of education can engender greater learning and understanding, leading to empowerment through active learning and enhanced potential for real change. This is where the overlaps between development education and active global citizenship become clearer as the activism arising from development education becomes enmeshed in everyday life as personal and social innovation.

A strong local and global dimension is important in development education and one which DEN-L has successfully amalgamated in its work. Development education in Ireland can be hampered by the division between what is a local development issue and what is a global development concern as development education tends to be globally focused and thus any activism arising is the same. But there is poverty and corruption in Ireland; we have resource issues, land rights concerns and migration issues too. By keeping the focus on the global dimension and on the far-away, the opportunity to engage in local orientated innovation and change that could have global consequences is missed. Understanding how local change and development impacts on the global and vice versa is the key learning. This type of development education does not deny the need for Southern voices and global perspectives to be included – as Regan (2011) argues, the key question for development education in the West is where is Africa in this? But the inclusion of local content provides a framework to activism and agency beyond campaigning or fundraising and can bring behaviours closer to the ideal of global civil society.

Conclusion

This is primarily a personal reflection piece on the relationship between development and development education, addressing questions I had been struggling with. From my participation in a development education exchange with DEN-L in 2010, I had questions as to the type and form development education may take in developing country contexts, associating local orientated development education with community development work. Similar questions arose in class discussions on the Masters in Development Practice in MIC on how development education can work to address local development concerns yet be something different to community development work. Finally I had questions on activism and mobilisation for development arising from development education.

Downs’ table identified five types of development education in a useful manner highlighting the differences between forms of education about, for, as development. His language and titles required some updating so I adapted his work for use in class. In summary Type 1 education about development creates nothing more than understanding, and does not call for any action. As argued by Wade and Hicks, awareness and knowledge alone does not engender change. Type 2 education for development creates informed and aware citizens, but their action arising remains at the fundraising level – a soft action resulting from development education. Type 4 education for development is an educational process creating informed, motivated and able learners, aware and empowered to campaign for change; however the change they work towards can be centred on the local and national arena rather than global. Type 3 and Type 5 both include local development challenges, however Type 5 advocates for personal and lifestyle innovation and agency while Type 3 could be influenced by modernisation accounts of economic development and growth. Seeing the five types in a clear manner, identifies clearly the need for local and global development content to be included within an understanding of their mutually productive and influential relationship and within the rapidly changing, interdependent and unequal world Irish Aid state in their definition of development education.

The questions I had about national variations of development education became clearer when the ‘Geographical focus of work’ and ‘development theory’ were added to the table. These new rows aided my understanding of the differing forms of development education in different contexts and places, and identified influencing factors as to the form a programme takes. The question I had concerning the expectation of activism and change-orientated agency arising from development education was also addressed by the inclusion of local development issues. However this highlighted the paradox that more critically informed activism and social innovation required a local and personal focus rather than a global dimension for activism to become a way of life and to move beyond charitable actions. This analysis has implications for the monitoring and evaluation of development education work briefly described above. More critical and engaged types of development education which impact most on the learner and create the most significant long-term attitudinal change and work to transform social, cultural, political and economic structures require the inclusion of local development issues as central to agency and innovation.

Note on Language:

I use the generalised terms Northern to denote the over-developed world of Europe, North America and other G8 countries while Southern denotes the under-developed areas of Asia, African and Latin America. I am aware these terms are general and greatly simplify the diversity of economic and political situations in both regions.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank the participants of the Masters in Development Practice, Mary Immaculate College, Limerick for engaging in much debate and discussion on this topic. Our seminars were Freirean dialogic learning in practice and were greatly inspiring. I would also like to thank the participants of the Advanced Development Education in Practice course for fruitful discussions, especially the coordinating organisations Development Perspectives, Dundalk, Ireland and DEN-L, Gbanga, Liberia. I endeavoured to make contact with Ed Downs, the original author of the table to discuss his work and to ask permission to reproduce it here. Unfortunately I could not make contact. If he reads this paper, I would welcome his comments and feedback.

References

Alden, C (2005) ‘China in Africa’, Survival: Global Politics and Strategy, Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 147-164.

Akande, D (2003) ‘The Jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court over Nationals of Non-Parties: Legal Basis and Limits’, Journal of International Criminal Justice, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 618-650.

Andreotti, V (2006a) ‘Soft versus critical global citizenship education’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 3, Autumn, pp. 40-51.

Andreotti, V (2006b) A Postcolonial Reading of Contemporary Discourses Related to the Global Dimension in Education, available: http://www.osdemethodology.org.uk/keydocs/andreotti.pdf (accessed 16 October 2013).

Bourn, D (2012) ‘Educación para el desarrollo: de corriente minoritaria a corriente establecida’/ ‘Development Education: from the Margins to the Mainstream’, The International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, Numero Uno (Febrero 2012), available: http://educacionglobalresearch.net/issue01bourn/(accessed 20 August 2013).

Church, R J H (1969) ‘The Firestone Rubber Plantations in Liberia’, Geography, Vol. 54, No. 4, pp. 430-437.

Downs, E (1993) ‘Placing Development in development education’, conference paper, University of Central Lancashire, Reproduced in the London South Bank University Reader for Unit 1: Introduction to Environmental and Development Education, London: South Bank University.

Fiedler, M (2007) ‘Postcolonial Learning Spaces for Global Citizenship’, Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 50-57.

Fien, J (1993) ‘Environmental Education: A Pathway to Sustainability’, reproduced in the London South Bank University Reader for Unit 1: Introduction to Environmental and Development Education, London: South Bank University.

Fien, J (1991) ‘Towards school-level curriculum enquiry in environmental education’, Australian Journal of Environmental Education, Vol. 7, pp. 17-30.

Freire, P (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Graves, J (2002) ‘Developing a global dimension in the curriculum’, The Curriculum Journal, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 303-311.

Hicks, D (2006) Lessons for the Future: The missing dimension in education, Victoria BC: Trafford Publishing.

Irish Aid, (2006) Development Education: Describing... Understanding … Challenging, available: http://www.developmenteducation.ie/resources/development-education/irish-aid-and-development-education-describing-understanding-challenging-the-story-of-human-development-in-todays-world.html (accessed 8 August 2013).

Jefferess, D (2008) ‘Global citizenship and the cultural politics of benevolence’, Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 27-36.

Krause, J (2010) European Development Education Monitoring Report: DE Watch, available: www.coe.int/t/dg4/nscentre/ge/DE_Watch.pdf (accessed 8 August 2013).

Mesa, M (2011) ‘Evolution and future challenges of development education’, The International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, Numero Zero (October 2011), available: http://educacionglobalresearch.net/en/manuelamesa1issuezero/ (accessed 20 August 2013).

Mignolo, W (2007) ‘The Splendors and Miseries of “Science”: Coloniality, Geopolitics of Knowledge and Epistemic Pluriversality’ in B.de Souza Santos (ed.) (2007) Cognitive Justice in a Global World: Prudent Knowledge for a Decent Life, New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

Orr, D (1991) ‘What Is Education For? Six myths about the foundations of modern education and six new principles to replace them’, The Learning Revolution, available: http://www.context.org/iclib/ic27/orr/ (accessed 8 August 2013).

Regan, C (2011) Keynote speech at Centre for Global Education conference titled ‘Reflections and Projections: Mapping the Past and Charting the Future of Development Education’, 24 February 2011, available: https://docs.google.com/file/d/0Bwa0-yj_NbZGNGNiNTNlNDktMjg2Ni00MjNkLWI3NGYtNmU2YTUwNzM1OWI4/edit?usp=sharing (accessed 8 August 2013).

Rosling, H (2011) The Magic Washing Machine, filmed Dec 2010, posted March 2011, TED Women, available: http://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_and_the_magic_washing_machine.html

Rostow, W (1960) The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sachs, W (1992) The Development Reader: A Guide to Knowledge and Power, London: Zed Books.

Tormey, R (2003) Teaching Social Justice: Intercultural and Development Education Perspectives on Education’s Context, Content and Methods, Limerick: Mary Immaculate College, and Dublin: Ireland Aid.

Wade, R (2006) ‘Journeys around Education for Sustainability: mapping the terrain’, London: WWF/LSBU.

Williams, R (1961) The Long Revolution, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

World Bank (2012) World Development Indicators- GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$) and Access to an improved water source, available:http://data.worldbank.org/country/liberia (accessed 20 August 2013).

Mags Liddy is completing her PhD thesis at the University of Limerick exploring the capacity of overseas volunteering as a professional development experience for teachers. Additionally she is coordinator of the IDEA Research Community, part of the Irish Development Education Association. Formerly she was Research Associate with the Ubuntu Network, a teacher education research project based at the University of Limerick from 2006 to 2010.