Education for Sustainable Development and Political Science: Making Change Happen

Development Education Without Borders

Introduction

This article looks at the potential benefits of a more symbiotic relationship between Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and Political Science, both in terms of theoretical understanding and practice. In a previous issue of Policy and Practice, Selby and Kagawa (2011) highlighted the need for both ESD and development education (DE) to ask the big political questions and to engage more critically with the current economic and political hegemony. With this in mind we examine here the mutual benefit of a closer engagement between ESD and Political Science. This article is the result of a collaboration between a Political Scientist (Hugh Atkinson) and an experienced ESD academic and practitioner (Ros Wade), and is a culmination of discussions which have taken place over the last two years. It has been developed from our experiences over three years at the Political Studies Association (PSA) Annual Conference where sustainable development was barely on the agenda. As a result of this, for the last three years we have run a PSA panel on ‘Politics and ESD’ which has attracted growing interest and has now developed into a specialist group.

The article is also drawn from many years of experience working in ESD and with ESD literature which rarely interacts with politics and political agendas per se. The need for greater synergy between the two areas was also strongly supported at the 2012 Sustainability Summit at the University of Leuphana, Germany, which brought together ESD colleagues from all over the world. This is a huge challenge, of course, and clearly the word limit constraints of writing a journal article mean that we are unable to cover all the wider issues and implications which are involved in this. Here we aim to map out some of the parameters and introduce some key ideas which will be expanded on and further developed in a book commissioned by Policy Press, to be published in 2014.

The focus in this article is on ESD rather than DE but we write as engaged academics who have worked in both areas. Without revisiting the relational history between the sectors, we see ESD and DE on a spectrum, with both working together for social and ecological justice though their emphases may differ. They are both contested terms, open to varying perspectives, depending on the ideology of their proponents. We are very aware that they have different histories and dynamics (Hogan and Tormey, 2008; Wade, 2008; Wade and Parker, 2008) but both ESD and DE have been open to capture by mainstream agendas as has been highlighted by Selby and Kagawa (2011) who ask whether they have been ‘striking a Faustian bargain’ with neoliberal, economic growth perspectives that run counter to achieving sustainable development. Selby and Kagawa remind us that central to all ESD and DE debates about change is the issue of power and, in order to address this, we maintain that there is a need for an understanding of political processes and systems, and this is where Political Science can make a contribution. At the same time, central to a relevant and coherent discipline of Political Science is an engagement with the key challenges of sustainable development and this is where ESD can contribute.

ESD and Political Science in context

The 1987 Brundtland Report defined sustainable development as ‘meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ and since then the concept has continued to be critiqued and to evolve. Central to sustainable development is the urgent need to tackle climate change which Giddens (2009) has described as a more important policy challenge than social justice. There is a close link between sustainable development per se and education for sustainable development: ESD can be viewed as the learning (formal, non-formal and informal) that is necessary to achieve sustainable development (UNESCO, 2007). This covers a very broad spectrum from formal sector education to community activism, social learning, organisational learning and awareness raising. This presents immense challenges and hence ESD needs to draw on a wide range of disciplines.

The American Political Studies Association (APSA) defines Political Science as ‘the study of governments, public policies and political processes, systems, and political behaviour. Political science subfields include political theory, political philosophy, political economy, policy analysis, comparative politics, international relations and a host of related fields’ (2013). For the purposes of this article, we are referring to the aspect of Political Science that focuses on political institutions, political processes, ideology, pressure groups, power and decision making and policy change. Political Science has produced a vast array of academic literature, an analysis of which is beyond the scope and purpose of this article. However, reference will be made to aspects of the literature which will help inform our general thesis of a more symbiotic relationship between ESD and Political Science.

Both ESD and Political Science recognise the need for systems thinking in order to understand social, political and economic processes. Yet ESD as currently constructed pays only limited attention to ideology and power relations and Political Science can bring something to the table here. ESD is about social change and Political Science can offer skill sets and routes to change with its understanding of the nature of barriers to change, of how political systems work and of how the levers of power operate. ESD is limited in its understanding of power relations while having such an understanding is a strength of Political Science. Central to ESD is its interdisciplinary nature. Political Science also recognises the importance of such interdisciplinarity. There is real potential here to develop practice as well as important research agendas.

ESD and the political context

The world is facing some very serious social and environmental challenges over the next fifty years. These include climate change, global poverty and inequality, war and conflict, and peak oil, all set against a backdrop of highly consuming lifestyles and a growing world population which is likely to reach nine billion by the end of the century. Yet governments have been extremely slow to address these issues. One of the obstacles to change has been a reluctance or an inability to integrate social and environmental concerns into policymaking and practice. Politicians have been slow to take up the challenge, both from lack of understanding and a piecemeal approach to policy and from a lack of political will. Discussions in one of the high level groups during the UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation) ESD mid-decade Bonn Conference underlined this issue when delegates identified politicians and policy makers as a key target for ESD (Wade, 2009).

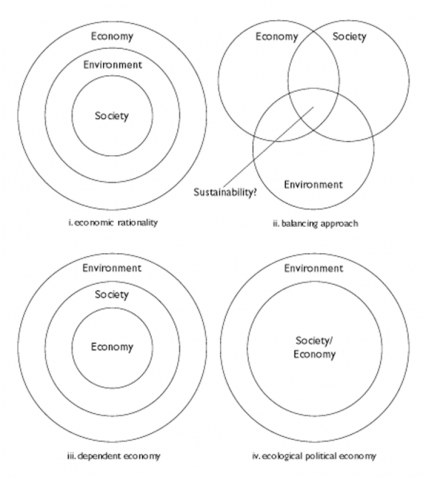

Figure 1: UNESCO’s three pillars of sustainable development

UNESCO identifies the three pillars of sustainable development as environment, economy and society, and the concept of sustainable development was devised to try to promote a new way of thinking which incorporated these elements. Despite its contested nature, it does at least provide a starting point for a new vocabulary of political change and the term has become increasingly used in mainstream policymaking over the last ten years. The four diagrams above in Figure 1 indicate different ways of approaching the term, all of which are open to differing political interpretations.

Diagram i shows a view which privileges economic concerns above the environment and sees society as a sub section of the economy – this could be said to demonstrate the current status quo. Diagram ii shows a series of overlapping circles in a Venn diagram. The central overlapping section where social, economic and environmental interact represents sustainable development. This seems to assume that somehow these elements of our daily lives can be divided and separated from each other. It is a diagram much favoured by those who support the business as usual, economic growth model for our planetary future. We would argue that economic perspectives are privileged in most policy contexts despite evidence of their limitations.

Diagrams iii and iv show all social activity taking place within the carrying capacity of the earth’s environment, with economic activity as an element of social activity. To us this demonstrates a more accurate reading of the context we are in. We are living on an island in space with the nearest other planet 40,000,000 km away. For the foreseeable future, this small and precious planet is the only home we have. Yet according to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF, 2009), if everyone in the world were to lead consumerist lifestyles like we do in the richest countries then we would need at least three planet earths to provide the necessary energy and resources. Because we are already living in a climate changed world, the main discussion centres on how many degrees of warming will we have to contend with (Lynas, 2007). Business as usual is not an option.

Diagram iii places economic activity firmly within the social domain, a reminder that it is people who create economic activity and who create markets. In addition, it challenges the notion of the pre-eminence of the economy over other areas of social activity. The economic lens through which we tend to look at the world these days is relatively recent – two hundred years ago religion and the state held much greater sway. Now it is surely time that we adopted a more relevant perspective for framing the twenty-first century – through the lens of social and ecological justice. This is where ESD and Political Science come together: what we are alluding to here is nothing less than a paradigm shift in the way that societies are organised, and in the way that we relate to each other and to the planet. Such changes need not only education but also political will and commitment.

After the first Earth Summit of 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, which drew up an extensive blueprint for sustainable development in the text of Agenda 21, education was seen as an essential element within it and commitments to education proliferated in the text. In addition, a whole chapter (Chapter 36) was devoted to the ‘Promotion of education, training and public awareness’. Crucially, this committed the world’s governments to ‘re-orienting education towards sustainable development’ (Quarrie, 1992: 221) and set out a basis for action, with clear, fully-costed strategies and activities to achieve it. Agenda 21 was an impressive political achievement in its own right in bringing about a policy consensus of all the world’s governments on the issue of sustainable development. Unfortunately, many of these commitments, such as those on education, were very slow to have any impact, and as early as 1996 UNESCO was reporting that ‘education [is] the forgotten priority’ and ‘is often overlooked or forgotten in developing or funding action plans at all levels, from local government to international conventions’ (UN, 1996).

As governments were so slow to take the initiative, this role was mainly taken up by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and committed activists. Their work tended to have two strands: one of support, training and awareness raising for educational practitioners, and the other of advocacy and lobbying for policy change. The ESD Programme at London South Bank University (LSBU) was itself a result of this engagement when, in 1993, a consortium of environmental and development NGOs came together to design a Masters’ course which would support practitioners and activists (www.lsbu.ac.uk/efs). At an early stage, therefore, it could be said that there was a strong connection between ESD and political activism (Wade, 2008).

The UN Decade of ESD 2005-2014

A consortium of NGOs also lobbied governments to make good their commitments at international level through the UN Commission for Sustainable Development (CSD) which was set up to monitor progress on Agenda 21. However, initial progress was slow in achieving this. So, with the strong support of a few governments like that of Japan, lobbying was successful in giving education for sustainable development the status of a UN Decade from 2005 to 2014. Education is now viewed as a prime lever for social change, described by UNESCO in the implementation plan for the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in the following way: ‘It means education that enables people to foresee, face up to and solve the problems that threaten life on our planet’ (UNESCO, 2005).

Policy and practice in ESD have certainly developed considerably since the start of the decade. For example, the Gothenburg Recommendations on ESD (2008), adopted on 12 November 2008 as part of the UN DESD, called on ESD to be embedded in all curricula and learning materials. In a number of countries there is now a developing government policy in areas of the formal education sector, from schools to higher education. In Denmark, for example, ESD has been introduced into key aspects of the curricula with a focus on children, young people and adult learners (The Danish Ministry of Education and Children, 2009). In the Netherlands, ESD has become an important element of the formal curriculum from primary school to higher education (Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, 2008). In Wales, ESD has been embedded in the curricula with a focus on schools, youth, further education and work based learning, higher education, and adult and continuing education (Welsh Assembly, 2006). In addition, national legal requirements on sustainable development in relation to other sectors, such as the built environment, have created space and the demand for training at a range of levels.

At the international level, education was further endorsed at the Rio +20 World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in 2012. This also highlighted the importance of links between ESD and Education for All (EFA: basic education as a requirement for the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) on poverty reduction). With the deadline fast approaching for the achievement of the MDGs by 2015, the concept of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is also beginning to be discussed at international policy level and, if adopted, this could give further impetus to the ESD and Political Science agenda (Sachs, 2012).

However, the key question for the SDGs is what kind of education is required if we wish to live sustainably? Certainly, current educational practices have been found wanting. David Orr reminds us that:

“Education is no guarantee of decency, prudence or wisdom. Much of the same kind of education will only compound our problems. This is not an argument for ignorance but rather a statement that the worth of education must now be measured against the standards of decency and human survival – the issues now looming so large before us in the twenty-first century. It is not education but education of a certain kind that will save us” (2004: 8).

The urgency of these issues was highlighted recently at Rio +20 where the key role of education was again endorsed by policymakers and practitioners. ‘At the Sustainable Development Dialogues, organized by the Brazilian government in the lead-up to the conference, three of the top ten key actions stakeholders voted on – out of a total of 100 – concern education’ (UNESCO, 2012). The challenge for ESD is to ensure that policy becomes practice and this is where Political Science can play an integral part.

Education as presently constructed can be broadly divided into three orientations: the vocational/neo-classical, the liberal progressive and the socially critical. Practitioners of ESD tend to position themselves mainly with ‘socially critical’ education where ‘the teacher is a co-ordinator with emancipatory aims; involves students in negotiation about common tasks and projects; emphasises commonality of concerns and works through conflicts of interest in terms of social justice and ecological sustainability’ (Fien, 1993: 20). However, this orientation tends to portray knowledge as mainly socially constructed and some say that it fails to give enough weight to the learning needed to live within the set biophysical boundaries of our world. In addressing some of the issues relating to the politics of knowledge, Janse Van Rensburg identifies one key challenge for educators: to find and use theoretical frameworks which enable ‘the acknowledgement of wider ways of knowing – in ways which open up greater possibilities in the re-conceptualisation of socially and ecologically appropriate development processes’ (1999: 18). This is a big challenge in an era when it seems that economic ways of knowing dominate all other narratives.

UNESCO as the lead international UN agency in promoting ESD describes it as being ‘facilitated through participatory and reflective approaches and is characterised by the following’:

- is based on the principles of intergenerational equity, social justice, fair distribution of resources and community participation, that underlie sustainable development;

- promotes a shift in mental models which inform our environmental, social and economic decisions;

- is locally relevant and culturally appropriate;

- is based on local needs, perceptions and conditions, but acknowledges that fulfilling local needs often has international effects and consequences;

- engages formal, non-formal and informal education;

- accommodates the evolving nature of the concept of sustainability;

- promotes life-long learning;

- addresses content, taking into account context, global issues and local priorities;

- builds civil capacity for community-based decision-making, social tolerance, environmental stewardship, adaptable workforce and quality of life;

- is cross disciplinary. No one discipline can claim ESD as its own, but all disciplines can contribute to ESD;

- uses a variety of pedagogical techniques that promote participatory learning and critical reflective skills”.

UNESCO further describes ESD related processes as involving:

- “Future thinking: actively involves stakeholders in creating and enacting an alternative future;

- Critical thinking: helps individuals access the appropriateness and assumptions of current decisions and actions;

- Systems thinking: understanding and promoting holistic change;

- Participation: engaging all in sustainability issues and actions” (UNESCO, 2007).

Above all, ESD is concerned with change – in ways of thinking, being, acting – on all levels, from the personal to the political, from local to global. This is illustrated by the ongoing discourse on ESD competences which is ‘based partly on the presumed lack of relevance of current educational provision and the need to produce ‘change agents’ (Mochizuki and Fadeeva, 2010). In 2010 UNECE (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe) produced a handbook of ESD competences for teachers which demonstrates the iterative nature of values and ethics, systems thinking, knowledge, and emotions with behaviour. While there are critiques of the competence agenda (for example, Lotz- Sisitka and Raven, 2009), the whole discourse highlights the importance of ESD as learning for action towards sustainability.

ESD: what can Political Science bring to the table?

This section will focus on how Political Science as a discipline can contribute to ESD and how the emerging area of ESD can contribute to Political Science. Here it should be noted that ESD is not considered as a discipline in its own right but rather as an inter and cross disciplinary field. As stated by UNESCO (2007) above, ‘No one discipline can claim ESD as its own, but all disciplines can contribute to ESD’. Up to now, we would argue, Political Science and ESD have had little interaction, to the detriment of both. Whilst there is evidence in Political Science literature of an engagement with the broader education debate (Jackobi, 2009; Orr, 2004) there is little if any reference to ESD.

Both Political Science and ESD are concerned with change at the level of policy and practice so there is real potential for symbiosis. Yet there is little evidence of this within ESD literature. This is perhaps a reflection of a wider malaise with the education community generally where there seems to be a marked reluctance to engage with the language of political change.

Yet at the same time there is a clear acknowledgement of education as a political football, kicked this way and that by prevailing political agendas. However, what is often missing is any comprehensive analysis of how educationalists can engage with these agendas. In the case of ESD, we would argue that educators need some understanding of Political Science as this is essential in order to understand how best to effect change.

ESD is about change – but also about conservation – of our ecological life support system and of the social structures which help us flourish as human beings. ESD is about the future but also about the present and it takes account of the past. ESD involves critical perspectives on change as many changes can be negative and destructive of human and ecological prosperity. The concept of sustainability, however, provides some basic guidelines for assessing whether change is good or bad. Sustainability is about making links in our complex world and often there are no easy answers. Bringing together agendas for change on social justice and ecosystem health means that we need to explore different theories of the relationships between social justice and ecosystem health. Globally, we need to keep in mind existing disparities in wealth and power, and the contrasts between high-consumption communities and low-consumption communities, identified in the ‘ecological footprinting’ concept. This is a potential area for collaboration between ESD and Political Science.

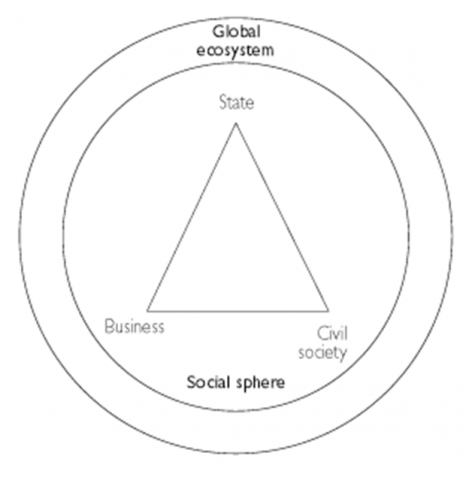

ESD adopts a holistic approach to understanding the world, recognising the iterative nature of policy and practice and the linkages and mutual dependence of ecological, social, cultural, economic and political relationships. This is illustrated in Figure 2 below, which sets out the interaction and connectivity of the three key social sectors interacting within the social sphere, which itself is dependent on the global ecosystem.

Figure 2: The interaction and connectivity of three key social sectors (from Parker, 2009).

Both ESD and Political Science accept the importance of systems thinking when attempting to understand economic, political and social organisms and how to effect change. Yet ESD has some conceptual problems in determining how such change might take place. Political Science can bring something to the table here. It can provide a context for ESD. There is potential in the following areas:

1. Understanding political systems and the power relations within them

ESD is limited in its understanding of the nature of power in political systems. Political Science can provide an explanatory framework and analysis of the levers of power, how power is developed and how it is used in a variety of ways to help shape the policy agenda. It can also help us to understand which levers to pull and the bells to press as well as the limits of action (Hague and Harrop, 2010; Heywood, 2011).

2. Understanding the role of pressure groups and social movements in shaping the policy process

Political Science can give us an understanding of the policy process (Hill, 2007; Knoepfel, 2011; Weiner and Viding, 2010). It has the potential to offer insights into the factors that impact on the ability of pressure groups and social movements to effect change. It has the potential to offer skill sets and routes to change. This could include skills in lobbying, advocacy (including the important ‘skills and capacities for resistance and transgression’ mentioned by Selby and Kagawa, 2011), as well as skills for developing policy manifestos and targeting efforts with limited resources.

3. Understanding political systems and the role of ideology

Change takes place (or not as the case may be) within the framework of ideology. Ideologies reform, adapt, become dominant or decline, wax and wane due to a variety of factors. ESD envisions a change in the way we do things. Political Science can provide some explanation of the ideological framework in which such change takes place (Ball and Guy Peters, 2005; Heywood, 2013).

Selby and Kagawa (2011) argue that ‘neoliberal growth and globalisation are ... clearly complicit in deepening poverty and injustice and in harming the environment’. There is validity in this statement. However, while it is true to say that neoliberalism with its emphasis on economic growth has been the dominant paradigm for three decades, it is an ideology and political approach which covers a broad spectrum. Political Science helps us to understand in a more nuanced way the complexities of different political systems and ideologies. The credit crunch of 2007-08 has forced a reappraisal on the part of governments about the more rampant laisssez-faire elements of neoliberalism. In other words, ideology and political systems are not static but are open to change, however problematic and intermittent. There are opportunities for ESD to engage more deeply and more effectively in these debates informed by Political Science.

4. Understanding the nature of political institutions

Political Science can give us an understanding of the way in which political institutions work (Hague and Harrop, 2010; Heywood, 2013). To effect change one needs to understand the nature of political institutions and political leadership at the global, European, national and local levels. Political leaders and political institutions tend to operate in the short to medium term. The kind of change inherent in ESD, for example radically changing our lifestyles to combat climate change, is in many ways outside the normal framework of political discourse. What we are referring to here is on-going and long-term. Politicians tend not to think in the long-term with their actions often shaped by the exigencies of the electoral cycle. In short they want to get elected. The demands of ESD might appear to be at odds with this view. Whilst Political Science can offer no magic cure to such a set of circumstances, it can at least help to set out the problems and offer some possible solutions. In particular, Political Science needs to start a debate about how political leaders and political institutions can reinvent themselves to prepare for the colossal challenges that tackling climate change and building a more sustainable world present. Are decision makers able to take the enormity of this on board, let alone present such a manifesto to the electorate?

5. The sustainable development agenda and political democracy

Linked to the last point is a fundamental question: how do we move to a politics in which political parties are honest with voters about the need to use less energy, to fly less, to use our cars less and to forsake the latest high tech gadget? The spread of ‘democracy’ over the last two decades has corresponded to a significant degree with the era of relentless growth in carbon dioxide emissions and fossil fuel depletion. Taken together with the current global economic crisis these realities present significant challenges for our political leaders. Are they capable of making ‘brave decisions’ (in the words of the civil servant from the BBC comedy Yes Prime Minister)? Such decisions involve spelling out clearly what has to be done if we are to make the world more sustainable and tackle climate change. This will require real sacrifices by Western consumers. How will they respond at the ballot box to such an agenda? Will our political leaders resort to the default position of short term expediency? There is no magic wand available here but Political Science has a major role to play in helping to frame this debate. In order to achieve this there is a need for a Political Science that is more relevant and that addresses real world political problems (Crick, 2005; Flinders, 2012; Rothstein, 2010; Schram and Caterino, 2006; Stoker, 2010; and Wood, 2012).

Political Science: what can ESD bring to the table?

Just as ESD can learn from Political Science so too can Political Science learn from ESD in a number of ways. As Matthew Flinders points out in Defending Politics, the discipline has undoubtedly been affected by the fact that ‘large sections of the public are more distrustful, disengaged, sceptical and disillusioned with democratic politics than ever before’ (2012: vii). Flinders argues that ‘for too long “politics” has been defined as involving politicians, formal political processes and political institutions like legislatures and parties’ (133) and stresses the need to include civil society as playing an active role in order to address the key challenges of the twenty-first century.

1. ESD offers a framework for understanding environmental and development issues

There are still many tensions evident within policy and practice between environmental and development issues. Politicians, concerned about winning elections, often seem reluctant to promote awareness raising of the major global and local challenges to the general public in any meaningful way. The issue of peak oil and the implications for our future energy use are often passed over in the wake of tabloid headlines about the rising price of petrol. Politicians and journalists themselves seem unable (or unwilling) to grasp the implications for our future way of life. Political Science has a duty to address this and to take a lead in establishing policy frameworks which can address it. ESD can offer a framework to develop this understanding. As Flinders argues, ‘The time has come for politicians to be a little brave and accept that there are limits to growth and that patterns of consumption and lifestyles need to change’ (ibid: 132).

For example, an understanding of sustainable development is essential for achieving the links between the MDG goals of poverty reduction and environmental sustainability (Wade and Parker, 2008: 9). The need for this is illustrated by the fact that out of all of the MDGs, the achievements in relation to the commitment to environmental sustainability (MDG 7) are very mixed. Whilst there has been some progress in reforestation in Asia (led principally by China) overall deforestation continues apace, biodiversity is declining and greenhouse gas emissions have reached record levels (UN, 2011). One of the reasons for this is that environmental and development agendas have still not come together in an effective way, particularly in relation to poverty reduction.

An understanding of poverty needs to take into account the dependence on the biophysical as well as the social environment. In addition, an understanding of these dependencies needs to be developed and explored more fully. The separation and tensions between the development agenda and environmental agenda illustrate to some extent the Western perspective of the split between the human and the natural world, a split which many feel is one of the major obstacles to sustainable development. Therefore, those of us who have been brought up in a Western educational/academic setting may have more to unlearn than those who have not. In many Southern and emerging countries environmental and development issues are more obviously interconnected and linked and there has not been a long history of separate constituencies. In South Africa, for example, Lotz-Sisitka points out that, ‘environmental education is strongly focused on the social, political, economic and biophysical dimensions’ (2004: 67).

However, we have to recognise that the dominant paradigm still operating in the world today is predominantly a Western one, which colours policy at both national and international levels. The tensions between environmental and development agendas need to be acknowledged and worked through and ESD can provide a framework for doing this. ESD has a strategic role in helping to address these tensions and move towards a clearer, more fully conceptualised and integrated form of sustainable development. This initiative needs to happen at all levels: international, national, regional, local, community, family, and individual. ESD is in a position to provide the framework for this. By its very nature, ESD necessitates the adoption of interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary approaches by establishing links across subject disciplines, across ministries and departments, and across formal and non-formal sectors. Thus, through a ‘multi-sectoral and linked up organisational learning, ESD has the potential the outcomes …for the MDGs.’ (Wade and Parker, 2008: 11).

2. ESD is by its nature interdisciplinary and can offer experience and expertise of this way of working to Political Science

An interdisciplinary approach is essential if we are to deal with the multi-faceted challenges of combating climate change and building a more sustainable world. Specialist disciplinary knowledge is always going to be relevant but at the same time ‘our assessment of positive ways forward and strategies for adaptation, mitigation and restoration life systems (including human social systems) must be based on more joined up forms of knowledge’ (Parker, 2010: 327)

While it is important not to underestimate the difficulties of working across disciplines, ESD draws from both the natural sciences and the social sciences and has experience in navigating some of the obstacles. The Education for Sustainability (EFS) programme at London South Bank University, for example, has over eighteen years experience in running an interdisciplinary post graduate programme. Students on the course come from a wide variety of backgrounds and geographical contexts, and have applied their learning in a range of settings. These contexts include the UK civil service, the health sector, schools and higher education (HE), conservation and development organisations. Course materials draw on a wide range of subject areas including Development Studies, Education, Social Science, Psychology, Ecology and Political Science. Students on the course are encouraged to make use of the theory to weave together their own learning patterns in relation to the context where they are working. In this way, the course has relevance to students from any region of the world and it has attracted students from a wide span of countries including the US, Japan, India, Tanzania, Colombia and beyond.

3. ESD involves a broad understanding of learning theory and processes and can help Political Science to engage with more participatory and interactive forms of learning and teaching

Human beings learn in different ways and a broad understanding of these different learning approaches is essential for effective education and change. ESD has developed a holistic and participatory approach to education (UNECE, 2005: 7) and has built up a repertoire of active learning processes which encourage engagement and action in addressing key issues. These include role plays, simulations, games and a wide range of activities which encourage critical thinking, reflection and questioning. Many of these are informed by the links which ESD has had with NGOs in the development and environmental fields. Much of the early impetus for ESD came from the work of development education centres (DECs) and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) like Oxfam and World Wide Fund for Nature and, as such, ESD is firmly grounded in action for real world change.

4. ESD can help Political Science to become more action orientated in addressing the key challenges of the day, such as poverty reduction in the context of climate change

By engaging with ESD, Political Science has the potential to be more action orientated towards real world problems. Through innovative course development, this could help to empower the next generation of agents for change in the political sphere. Many would-be policymakers and politicians undertake studies in Political Science and there is a real need to encourage them to tackle the difficult questions and to make ‘brave decisions’ for the long term benefit of people and planet. Courses which address real world issues could also have the added effect of encouraging student motivation and addressing the employability agenda with regard to graduate skills.

5. ESD can share expertise in working across sectors and across geographical regions

Political Science by its very nature engages with a wide range of political actors across all sectors. ESD can offer Political Science another avenue to address key issues, for example, through one of the initiatives for the UN Decade of ESD (2005-2014) where a number of regional centres of expertise (RCEs) for ESD were set up and endorsed by the United Nations University (UNU, see http://www.rce-network.org/elgg/#). These now form a global and regional network which has the aim to involve all sectors of society in the task of reorienting education towards sustainability. Most are based in universities and involve civil society, state and business networks which together are trying to address the sustainability challenges of the region where they are based, within the context of the global challenges which are faced by all of us on this planet.

In RCE Greater Nairobi this has involved a major focus on waste management in order to address the serious dangers of pollution and poverty. In RCE Rhine Meuse this has involved working with planning departments in promoting sustainable practices in housing and transport links. In RCE Sendai, it has involved addressing the aftermath and trauma of the Asian tsunami of 2004. This work has involved education and learning at all levels, both formal and informal, across a range of disciplines (Wade, 2013).

Political scientists can benefit from working with these UNU backed RCEs. RCEs are comprised of organisations that include higher education institutions, local government and community groups, NGOs and representatives from the business sector. These RCEs give political scientists a real opportunity at ground floor level to help shape the debate around sustainable development. Political scientists could benefit from exposure to new experiences and new ideas which might frame future research agendas. In addition, working with RCEs enables direct engagement with the regional political process and political actors and offers opportunities to students to become involved with action for sustainable change. RCE Crete, RCE Toronto and RCE Sendai all provide examples where students, academic and local politicians have worked together to promote change in their communities (ibid).

Conclusion

ESD can provide a framework for the collaborative, interdisciplinary approaches essential to developing the new learning and understanding needed if we are to address the very real sustainability challenges of the future. The understanding of political processes and power which Political Science can provide is also a prerequisite for the changes which are needed to achieve sustainable development for all.

This article has tried to show that there is a rich seam for both ESD and Political Science to tap into which might not only bear fruit in terms of innovative course development and cutting edge research but could also feed in a substantive way into broader political decision making and the shaping of public policy. Sustainable development is a key policy paradigm for the twenty-first century. We have offered some suggestions to take this forward, as we believe that by working together, ESD and Political Science can help to shape this paradigm.

References

Ball, A and Guy Peters, B (2005) Modern Government and Politics, Basingstoke, Herts: Palgrave Macmillan.

Brundtland, G (1987) Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development, New York: UN.

Crick, B (2005) In Defence of Politics, London: Continuum.

Danish Ministry of Education and Children (2009) Education for Sustainable Development: a strategy for the United Nations Decade, 2005-14, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Dutch Ministry of Education (2008) Learning for Sustainable Development, 2008-2011: From strategy to general practice, The Hague, Netherlands.

Flinders, M (2012) Defending Politics: Why Democracy Matters in the Twenty-First Century, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Giddens, A (2009) The Politics of Climate Change, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hague, R and Harrop, M (2010) Comparative Government and Politics, Basingstoke, Herts: Palgrave Macmillan.

Heywood, A (2013) Politics, Basingstoke, Herts: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hill, M (1997) The Policy Process in the Modern State, London: Prentice Hall.

Hogan, D and Tormey, R (2008) ‘A perspective on the relationship between development education and education for sustainable development’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 6, Spring, pp. 5-16.

Jakobi, A P (2009) Education in Political Science: Discovering a neglected field, Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Knoepfel, P, Larrue, C, Hill, M, and Varone, F (2011) Public Policy Analysis, Bristol: Policy Press.

Lotz-Sisitka, H (2004) Positioning southern African environmental education in a changing context, a discussion chapter commissioned by the SADC Regional Environmental Education Programme, for the purposes of informing the Danida funded ‘Futures Research’. Howick: SADC REEP .

Lotz-Sisitka, H and Raven, G (2009) ‘South Africa: applied competence in the guiding framework for environmental and sustainability education’ in J Fien, R Maclean and M G Park (eds.) Work, Learning and Sustainable Development, UNEVOC Technical and Vocational Education and training Series, Vol. 8, Heidelberg: Springer.

Lynas, M (2007) Six Degrees: Our Future on a Hotter Planet, London: Harper Perennial.

Mochizuki, Y and Fadeeva, Z (2010) ‘Competences for sustainable development and sustainability: significances and challenges for ESD’, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 391-403.

Orr, M (2004) ‘Political Science and Education Research: An exploratory look at two Political Science journals’, Education Research, Vol. 33, No. 11, pp. 11-16.

Orr, D (2005) ‘Preface’ in A R Edwards, The sustainability revolution: portrait of a paradigm shift, British Columbia, Canada: New Society Publishers.

Parker, J (2009) ‘An Introduction to Education for Sustainability’, Unit One Study Guide of the MSc Education for Sustainability, London: LSBU.

Parker, J (2010) ‘Competencies for interdisciplinarity in higher education’, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 325-338.

Quarrie, J (ed.) (1992) Earth Summit 1992, London: The Regency Press.

Rothstein, B (2010) ‘Should Political Science Be Relevant’, Inside Higher Education, available: http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2010/09/07/polisci (accessed 27 March 2013).

Sachs, J (2012) ‘Rio+20: Jeffrey Sachs on how business destroyed democracy and virtuous life’, Guardian, 22 June 2012, available:http://www.guardian.co.uk/sustainable-business/rio-20-jeffrey-sachs-business-democracy (accessed 29 October 2012).

Selby, D and Kagawa, F (2011) ‘Development education and education for sustainable development: Are they striking a Faustian bargain?’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 12, Spring, pp. 15-31.

Sohram, S F and Caterino, B (2006) Making Political Science Matter: Knowledge, Research and Method, New York: NYU Press.

Stern, N (2006) Review of the Economics of Climate Change. London: HM Treasury, HMSO.

Stoker, G (2010) ‘Should Political Science Be Relevant’, Inside Higher Education, available: www.insidehighered.com/news/2010/09/07/polisci (accessed 27 March 2013).

UNECE (2005) Strategy for Education for Sustainable Development, available: http://www.unece.org/env/esd.html (accessed 8 May 2013).

UNECE (2010) Competencies for ESD teachers, available:http://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/esd/inf.meeting.docs/EGonInd/8mtg/CSCT%20Handbook_Extract.pdf (accessed 16 July 2012).

UNESCO (2005) UN Decade for sustainable development 2005-2014, available: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001403/140372e.pdf (accessed 30 April 2013).

UNESCO (2007) United Nations Millennium Development Goals Report 2007, available: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/mdg2007.pdf (accessed 30 November 2007).

UNESCO (2007) ‘Introductory Note on ESD – DESD’, Monitoring & Evaluation Framework, Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2008) ‘Gothenburg Recommendations’, available: http://www.desd.org/Gothenburg/Recommendations.pdf (accessed 16 July 2012).

UNESCO (2012) available: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/rio-20/singleview/news/rio_20_recognizes_key_role_of_education/ (accessed 16 July 2012).

Wade, R (2008) ‘Journeys around Education for Sustainability: mapping the terrain’ in J Parker and R Wade (eds.) Journeys around Education for Sustainability, London: LSBU/WWF/Oxfam.

Wade, R (Rapporteur) (2009) Report on High Level workshop on ESD-EFA synergy, UNESCO Mid Decade Bonn Conference Report 2009, Unpublished.

Wade, R (2013) ‘Promoting sustainable communities locally and globally: the case of RCEs’ in S Sterling, H Luna and L Maxey (eds.) The Sustainable University, London: Routledge.

Wade, R and Parker, H (2008) EFA-ESD dialogue: Educating for a sustainable world, ESD Policy dialogue No 1, Paris: UNESCO.

Weimer, D and Viding, A R (2010) Policy Analysis: Concepts and Practice, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Welsh Assembly (2006) Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship: a Strategy for Action, Cardiff, Wales: Welsh Assembly.

Wood, M (2012) ‘An insider view on the relevance of political scientists to government’, available: http://blogs.lse.uk/impactofsocialscience/2012/05/30insider-view-relevance-political-scientists-government/ (accessed 10 April 2013).

Hugh Atkinson is a senior lecturer in politics and public policy at London South Bank University. His current research focuses on the links between politics, democracy and sustainable communities. He is the author of Local Democracy, Civic Engagement and Community: From New Labour to the Big Society (Manchester University Press, 2012).

Web site: www.hughatkinson.moonfruit.com

Twitter: @HughAtkinson

Ros Wade is Reader in ESD and Director of the Education for Sustainability programme at London South Bank University. Current research interests focus on ESD and social change and the potential of ESD learning communities of practice. Recent publications include a chapter in, S Sterling, L Maxey, and H Luna (eds.) The Sustainable University, (Routledge, 2013). She chairs the London Regional Centre of Expertise in ESD and is a member of UNESCO’s International Teacher Education network.

Website: www.rosw.moonfruit.com

Twitter: @RosWade1