The Visual Representation of Global Development Issues in a Higher Education Environment: Perception, Interpretation and Replication

Development Education in the Formal Sector

Abstract: What kinds of perspectives of global development issues are students exposed to through the visual imagery displayed in higher education institutes? This study explores the messages being communicated by these images and how they are interpreted by students and staff of a higher education institute in the Republic of Ireland. Following an overview of the theoretical literature, original fieldwork is presented, in which interviewees were invited to respond to visual representations of global development issues on display in the institute. The study looks at how these visual messages contribute to viewers’ perceptions of people from the wider world, particularly those who are vulnerable or living in poverty. It examines how students (and their educators) negotiate these messages and the ideological perspectives they represent, and the implications for their subsequent work environment and practice.

Key words: Messages; Visual Imagery; Visual Representation; Development Imagery; Photography; Teacher Education; Global Issues; Poverty.

In our visually mediated world we have come to ‘know’ many of the realities of our wider environment through witnessing visual representations of it, long before experiencing the actuality: we visit a new city online on Google Street View before we book the flight to our chosen destination; we take a virtual tour of our hotel before checking in. The visual in our culture, either in its static or moving forms, is afforded high status; Gregory refers to the favouring of ‘vision’ in ‘Western’ contemporary society (1994: 64); Rose reminds us of the increasing saturation of Western societies in particular by visual images, and suggests that ‘Westerners now interact with the world mainly through how we see it’ (2012: 3). An image can be an idea or even a memory, something we ‘see’ in the mind’s eye, so much so that it can be difficult to separate the actual image viewed from the imagined or remembered image.

The development sector depends heavily on photographic imagery for communication, publicity, information and awareness-raising purposes. Equally, imagery can be an effective tool for development educators to engage with learners on complex global issues. Although the issue of visual representation has been a focus for development practitioners and researchers for decades (Alam, 2007; Dogra, 2014; Lidchi, 1999; Lissner, 1977; Moeller, 1999; Pieterse, 1992; Said, 1978; Sankore, 2005; Sontag, 1979; Young, 2012), it is only relatively recently that theorists have turned to the issue of problematic representations of development in formal education (Bryan and Bracken, 2011; Honan, 2003; Jeffers, 2008; Smith and Donnelly, 2004; Tallon and Watson, 2014).

This article examines the ways in which global development issues are represented visually in the higher education institutional space, what key messages are being communicated by these visuals and how higher education students and their educators interpret or are influenced by these ideas. It presents an overview of the literature, outlining the theoretical backdrop of contemporary visual representation and the discourse surrounding the issue in the development sector; it addresses this under thematic headings, exploring the impact of visual imagery on perception, from the perspective of those viewing as well as those depicted. This is followed by an account of a consultative research project devised to explore these themes in the field. The project took a selection of visual representations of people living in poverty as displayed in a higher education institute in the Republic of Ireland, and interviewed staff and students to examine the impact of those visuals, studying their interpretation and, and the potential implications for their subsequent work and practice. This field research process and the methodology involved is outlined in greater detail below.

Theories of representation

Ways of seeing

Visual culture theorists suggest that we articulate knowledge visually to the extent that we conflate seeing with knowing: ‘Looking, seeing and knowing have become perilously intertwined’ to the extent that ‘the modern world is a seen phenomenon’ (Jenks, 1995: 1-2). In regard to photography (and video) in particular, there is a tension between the idea of an image as reality and the perception of it as ‘an artefact, … an expression of culture which needs to be read very much like a painting’ (Emmison, Smith and Mayall, 2012: 22–23). Dogra refers to the ‘truth claim’ of a photographic image, that is ‘the documentary-like or evidence effect’ which suggests it is real and actually happened (2014: 160).

Writers on visual culture, such as Sturken and Cartwright (2009), argue that it is not simply the image that is significant but how the image is looked at. They draw on Berger’s (1972: 9) assertion that ‘we never look just at one thing: we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves’. Images are polysemic, that is, they have multiple possible readings depending on the experiences, knowledge and perceptions of the viewer. Intertextuality – the way in which meanings of images or texts are reconstructed and reproduced around similar types of visual images – can also influence discourses around similar visual texts (Rose, 2012: 191). So, we consciously or unconsciously cross-reference when interpreting images of a similar genre.

The ‘Other’ imaged – recurring themes

Smith and Donnelly (2004) cite Gregory’s (1994: 64) description of the significant role played by vision in our ‘construction of “knowledge” of the “Third World” “other’”. Referencing Said’s seminal Orientalism (1978), the authors describe Said’s exposé of the ‘power dynamics of colonialism’ in visual representations of the Orient, a visualisation which Said asserted could not be separated from social relations. Drawing on Foucauldian theory, Said claimed that the ‘other’ was actually about ‘reflecting the self’ (1978: 208). The idea that ‘to see is to know’ was a ‘fundamental tenet of colonial domination and appropriation’, as well as a mistaken ideology of development practice (Smith and Donnelly, 2004: 129).

In Representations of Global Poverty, Nandita Dogra describes how the ‘construction and maintenance of “difference” between “us” and “them” or “the West” and “non-West”/“East”/“Orient’” informs ongoing colonial discourse and continues ‘to linger and inform the ways of seeing and representing “Other” cultures’” (2014: 12). Dogra extends her argument to include the ‘whole history of colonial imagery that did infantilise the non-West (McClintock, 1995; Mudimbe, 1988; Shohat and Stam, 1994)’, primarily through ‘the use of children as symbols’ (Dogra, 2014: 38), and ‘the representation of the Third World as a child in need of adult guidance’ (Nandy 1983, cited in Escobar, 1995: 30). This representation involves contradictory associations, including innocence, neediness, paternalism, helplessness, dependency, ignorance and underdevelopment.

Similarly, the predominance of women in development imagery is hugely symbolic and equally complex, drawing on associations with nature, motherhood, nurture, victimhood, tradition and vulnerability, as noted by Dogra (2014). She highlights for instance how ‘the form of the female figure, akin to that of a child, can project ideas of “nature” while hiding other ideas such as the historical background and politics of famines’. Such images misleadingly ‘project the women and children as a homogenously powerless group of innocent victims of problems that just “happen to be”’ (2014: 40). This overemphasis, in non-governmental organisation (NGO) imagery in particular, is also borne out by recent research commissioned by Dóchas in Ireland (Murphy, 2014) and by ASCONI (Young, 2012) in Northern Ireland. Murphy refers to the personal stories of women in direct fundraising appeals as more likely to be used in a way which ‘depicted the causes of poverty as internal to the developing country, or even the fault of the beneficiary herself’ (2014: 55). She also expresses concern at the significant portrayal of women in gendered roles (needy, dependent, primarily care-giving etc.), as explored by Dogra.

The Dóchas research draws on theories of ‘frames’ as developed by Darnton and Kirk (2011) in their major research project Finding Frames: New Ways to Engage the UK Public in Global Poverty, elaborating the theory in an attempt to understand and address the problematic public engagement model entrenched in the ‘Live Aid Legacy’ – the dominant giver/grateful receiver mode. Darnton and Kirk’s theory builds on the work of the cognitive linguist George Lakoff who ‘identified a number of “deep frames” which inform how we behave, how institutions are constructed, and how we think and talk about the world’ and ‘represent moral worldviews’ (Darnton and Kirk, 2011: 2). The Finding Frames report employs Lakoff’s theories to identify prevailing themes underpinning development practice. It identifies positive deep frames including participatory democracy, and negative surface frames including ‘charity’ and ‘aid’. Murphy (2014), who used the same methods of analysis as Darnton and Kirk in her study of frames emerging in the communication materials of Irish NGOs, found ‘charity’, ‘help the poor’ and ‘poverty’ to be the dominant surface frames here also. Murphy’s concern is that such negative framing ‘only serves to emphasise a divide between rich and poor, black and white, or superior and inferior’, reinforcing the ‘“us and them” mentality’ (2014: 52). Images of ‘Poster Children’ and women are also dominant in Murphy’s findings, that of women so significant that she coined a new category, the ‘Gender frame’ (ibid: 55).

Impact on perceptions

In a Suas national survey of 1,000 higher education students in Ireland, participants were asked to ‘identify the first word that came to mind when they heard the term “developing countries’”. The terms ‘“Third World” (18%), “Africa” (15%), “poor/poorer” (12%) and “poverty” (5%)’ featured in the proportions indicated (2013: 2). In an earlier DCI (Development Co-operation Ireland) study of development education effectiveness in Irish schools, Honan (2003: 21) reports ‘overwhelmingly negative images of the Third World’ in students’ responses. The research relates this negativity to what it terms a “black babies” and “assistencialist” approach to the issues, reinforced by ‘teacher attitudes and experiences, the role of the media and the constant fundraising and advertising activities of NGOs’ (Honan, 2003: 21, 41).

Sankore is concerned about the impact of ‘increasingly graphic depictions of poverty projected on a mass scale by an increasing number of organisations over a long period’, which he maintains must ‘impact on the consciousness of the target audience’. He describes the unintentional effects of potentially well-meaning charity campaigns:

“the subliminal message [is] … that the people in the developing world require indefinite and increasing amounts of help and that without aid charities and donor support, these poor incapable people in Africa or Asia will soon be extinct through disease and starvation. Such simplistic messages foster stereotypes, strip entire peoples of their dignity and encourage prejudice” (2005: para.6).

Keen also underlines the effect of a cascade of negative images: ‘If the only thing you get is the negative stories, you become inured and people seem less human’ (quoted in VSO, 2002: 11). This is not a new idea: Sontag (1979: 20-21) suggests that ‘the vast photographic catalogue of misery and injustice throughout the world has given everyone a certain familiarity with atrocity, making the horrible seem ordinary – making it appear familiar, remote, inevitable’. This ‘catalogue’ of imagery has become disproportionately associated with the global South. Bryan and Bracken suggest that because we are not exposed to the daily realities of people in Southern countries going about their business we tend to make broad assumptions and attribute the sensational or disastrous to the “‘African” or “Indian condition’” (2011: 123). Additionally, there is a tendency to perceive the global South as ‘a series of absences’ (Smith, 2006: 76).

Much of the typology of negative imagery includes a significant level of so-called development pornography – defined by one commentator as ‘the pictures of victims that show in shocking detail what’s happened to them, stripped of life and often stripped of dignity’ (Humphrys, 2010). Common in the media as well as in many NGO publicity campaigns, such imagery is also prevalent in school textbooks, as Bryan and Bracken’s 2011 study highlights. The authors point out that while development NGOs might attempt to justify the use of shocking imagery as a fundraising tactic, a rationale for its use in secondary school textbooks is ‘less clear-cut’ (2011: 112). They contend that students from countries in the majority world attending Irish schools can be upset and offended by textbook representations of their culture and nationality.

An indicator of the lasting power and impact of imagery on perceptions or ‘the still image lingering’ is evidenced in the strong associations which Ethiopia has for many people born well after 1984 (Clark, 2004: 12). Moeller describes the result of formulaic coverage where ‘iconic moments become symbols, then stereotyped references that become at best a rote memory’ (1999: 53). Beg (quoted in Smith, 2006: 24) asks if ‘the “developing” world is not static – then why don’t the images change constantly with the progress that is taking place?’ Moeller (1999: 43) suggests that there is a ‘built-in inertia that perpetuates familiar images’, an inertia that the public submits to as a result. She suggests that the inevitable consequence of formulaic or even sensationalised coverage is ‘compassion fatigue’ (ibid: 53). In the context of visual imagery, compassion fatigue refers to the phenomenon whereby graphic or upsetting imagery ceases to have an impact because it has been seen so many times before. Sankore believes that ‘fatigue has already set in’ and insists the result of a lack of clarity on the causes of poverty in the South will be a ‘backlash’ as ‘ingrained negative stereotypes’ lead to ‘ignorant prejudice’ (2005: para.13).

Such a backlash is already being felt by African diaspora communities. Young points to some of the particular effects on people of African origin living in Northern Ireland, including the perception of ‘Africans as helpless’ and the continent perceived as ‘a monolithic, undifferentiated region’ (2012: 22). Young asserts that individuals are ‘profoundly negatively impacted by these images and the messages they convey’. She shows that the imagery is part of a ‘broader narrative [which] implicitly emphasises the “otherness” of these individuals and groups and ostracises many new communities and reinforces the perception of them as on the periphery of society in Northern Ireland’ (2012: 38). As Manzo suggests, that stereotypical imagery affects not only how “‘we” see “them”, but also how “they” see themselves’ (2006: 11). Wambu also shows that stereotypes impact on young people of African origin living in the West, who ‘often feel negative towards Africa and seek to dissociate themselves from their place of heritage. This hinders their participation or engagement in Africa’s development’ (2006: 22). A quotation from a focus group participant from the diaspora in NI further points to the ‘psycho-social’ impacts: ‘These images have to erode at our social conscience as a people. African people start resenting each other, as it makes me feel different to them, and it destroys a collective people’ (Young, 2012: 25).

The image in the institution

As far as this author has been able to establish, no research to date, either in Ireland or elsewhere, has focused on the way in which global development issues are represented in the public spaces of institutes of higher education. Cox, Herrick and Keating point out that other than in reference to the architecture of schools, ‘until recently the nature of space and learning itself has not been greatly studied or theorised’ (2012: 698).

Similarly, there is a scarcity of academic literature on the actual visual spaces such as noticeboards or vertical display areas of educational institutions, notwithstanding the obvious connection between the visual and the spatial – that is, between an image and the context in which it is viewed. In a survey carried out on behalf of the Irish Traveller Movement in the former Froebel College of Education (Power, 2012), the issue of the institutional environment was touched on, where, in the context of creating a more inclusive campus, participants raised the issue of the images (and icons) on display there. As Emmison et al. emphasise, buildings are ‘not simply functional structures whose built form reflects imperatives of utility and cost. They also reflect the cultural systems in which they are embedded’ (2012: 153).

Field research in a higher education environment

The complex associations and reactions described in the theoretical framework above come into play whenever such images are used, whether in promotional material, in textbooks, or in public displays. The theory formed the backdrop for the research project carried out by the author between June 2013 and December 2015, which analysed a selection of images depicting global development issues which appeared on noticeboards in a higher education institute in Ireland. The institute in question specialises in teacher education and offers a range of undergraduate and postgraduate programmes in education-related studies including a B.Sc. in Education Studies and a Bachelor in Education (Primary) (B.Ed.).

The primary data used for analysis included sixteen semi-structured 30-minute interviews with staff and students (which were audio-recorded, transcribed and then coded). This interview data was supplemented by 35 completed research questionnaires which had been returned by a combination of staff and students. Initially an inventory was made of imagery in the institute depicting any aspect or reference to people or places in the global South. Approximately 200 photographs were taken of relevant imagery in noticeboards and public display areas in the college. The researcher selected twenty representative images and printed them in full-colour A4 format. Global themes depicted included trade, environment, equality, peace and conflict, poverty, play, culture including art and music, inclusion, aid and volunteering. Subsequent analysis showed that ten of these images derived from NGO sources, two from a government department, three from government or state-sponsored bodies, one from a national faith-based representative body, one from a faith-based foundation, four from lecturers’ own curricular-area-related displays, one from a student volunteering experience, one from a framed corridor photograph and one from an unknown source. Images were chosen to reflect a variety of compositions and themes, regardless of their source. These visuals were used to prompt and focus the discussions in all interviews with staff and students.

In this text all interviewees have been anonymised and numbered: student interviewees are referred to as ‘SD’ and staff as ‘SF’. As distinct from an ‘interviewee’, the term ‘respondent’, when used in this research, refers to any individual who returned a completed research questionnaire. A ‘participant’ refers generally to any respondent or interviewee who participated in the research process.

Discussion

A number of common themes emerged repeatedly in the interviews with staff and students who participated in this research. The breadth of this article does not allow for discussion of all of the key themes so I have selected a single overarching theme, Perspectives on Poverty, which exemplifies many of the issues discussed above.

When asked to identify common themes displayed in the selection of images of global perspectives drawn from the institute noticeboards and display areas, poverty was identified as a dominant issue by all staff and students interviewed. At least half of those interviewed named it specifically, with the remainder alluding to it through reference to associated issues (starvation, hunger, deprivation, struggle, hardship and so on). Responses to the idea or the image of poverty included pity, sadness, sympathy, shame, and even anger. A number of interviewees named empathy as an emotive response, although their actual understandings of the concept of empathy were not explored in any depth. The idea of people being ‘happy subjects’ and somehow resigned to their poverty was commonly expressed: ‘the kids there seem to be fairly resolute and, and happy with themselves, [despite] the situation they find themselves in’ (SD2). This conflation of poverty with either happiness, or equally sadness, seemed to be a pattern associated with a type of image or a genre of imagery and was expressed as a response to the idea of that genre, possibly sparked by viewing one or two suggestive images on campus: ‘That they’re, kind of, always sad, and they’re always in poverty’ (SD4).

In expressing strong feelings about the fact of poverty, the focus was on the problem, with little or no reference to the causes or possible solutions. Poverty was rarely understood as something which we have a stake in, except in terms of a moral obligation to help or feel guilty at our own relative fortune. Although the inequalities and power dynamics between North and South were fleetingly alluded to, it was only suggested by two interviewees and one questionnaire respondent that there might be historical, structural or political causes for these inequalities or that the North might be implicated in perpetuating them. Even where the inequality was acknowledged, it was presented as infinite, as a fait accompli: ‘that the wealth is not shared around and inequality is just reproduced throughout the years’ (SD2). The same student pointed out that:

“you never really see the person who has escaped the … poverty, or the, have overcome the overwhelming odds against them … When you give preference to one, eh, depiction say for instance, the poverty and what not, … [it’s] so prevalent that you don’t even think about an alternative” (SD2).

One particular appeal poster (permission for reproduction was withheld), which depicted a ‘small scared child’ (SD6) peeping around a doorway with the caption ‘Empowering the poor: Giving a voice to the vulnerable’, drew a lot of attention. This is a graphic example of the ‘Poster Child’ genre, where the child in the image acts as a signifier for the entire global South, portraying it as a ‘child in need of adult guidance’ (Escobar, 1995: 30). To respondents, this poster image more than any other, while not explicit, was suggestive of many of the stereotypical characteristics that people would associate with a familiar genre. Initial responses to this image included ‘pity’, ‘sorrow’ and ‘sympathy’ for the girl, acknowledging that it was ‘pulling on the heartstrings maybe a little bit’ (SD6).

A number of interviewees, who at first appeared to be moved by the image, on further reflection expressed irritation and cynicism because they noticed that the child looked ‘fearful’ or ‘vulnerable’, feelings which they perceived to be at odds with the message of empowerment promised by the poster wording. One student asserted that the caption itself was disempowering in assuming ‘do they not have a voice without it?’ (SD6). Arnold explains that the ‘charity vision’, which this kind of image represents was until relatively recently seen as the ‘motivating force … to inspire compassion and to awaken a sense of “moral duty” to help the less fortunate’ (1988: 188). A more graphic and extreme form of the genre constitutes what is often referred to as development pornography or poverty porn. The use of this kind of voyeuristic imagery has been widely condemned in development circles for decades and contravenes established codes of good practice on development imaging. Although there has been a shift of sorts from ‘a charity-based vision to one centred on empowerment’ (Arnold, 1988) recent research suggests that this shift is minimal. In their 2011 analysis of school textbooks Bryan and Bracken note numerous incidences of development pornography within current post-primary texts. In her recent study of Irish NGO public communications, Murphy suggests that the sector still frames poverty and charity in line with live-aid style ‘paradigms’ (Murphy, 2014: 52).

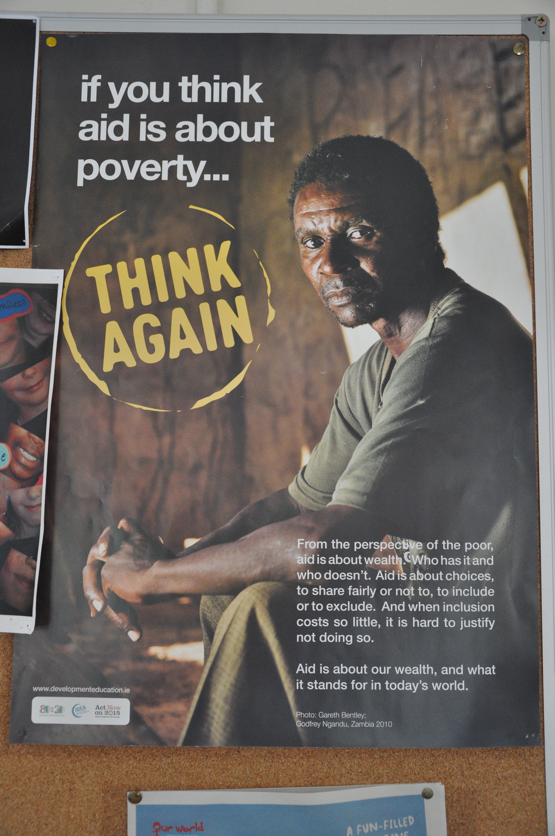

The ‘Think Again’ aid campaign poster (Image A) developed by the Irish NGOs 80:20 and IDEA (Irish Development Education Association) for educators drew a different kind of mixed response. The photograph, which depicts a seated Zambian, Godfrey Ngandu, staring intently at the camera, alongside the caption, ‘If you think aid is about poverty... Think Again’, was described by one student as ‘sad’, ‘very dark’ and ‘uncomfortable’ (SD7), and while the poster tries to explain the need for wealth sharing, and tries to ‘ask rather than tell’ (SD8), it manages to communicate a confusing and ‘contradictory’ message. Another student, uneasy with the same image, concedes that it does allude to the man’s ‘right’, with a suggestion that ‘it might be our fault that this is happening’. She elaborates that ‘it’s kind of, calling you to reflect on yourself, or maybe what you could do’ (SD8).

Image A

This poster certainly represented a departure from the norm displayed in the message it sought to communicate. However, the fact of its ambiguity meant that its message was diluted and the potential impact lost on many viewers.

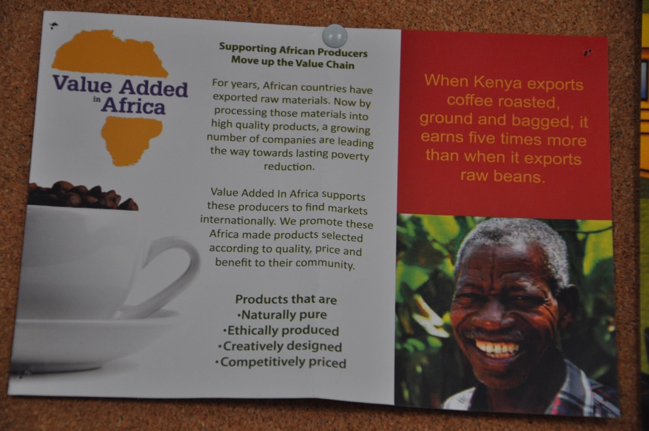

An example of a poster (Image B) which was more successful in connecting with viewers was the Value Added in Africa (VAA) campaign created to support their African producers. One student pointed out that its ‘business’ theme enhances the portrayal of the subject from simply ‘happy, healthy, content’, into someone who is genuinely empowered (SD6). Arguably, there is nothing distinctly business-like about the images used or the poster itself, but the combination of so-called positive imagery and a carefully balanced marketing blurb gives this poster more of an upbeat feel. The fact that trade justice is a theme which has been ‘imaged repeatedly without recourse to the iconography of childhood’ is noted by Manzo (2008: 645).

Image B

What appears to be counter-productive in many of the typical anti-poverty poster campaigns witnessed (both on campus and from interviewees’ memories) is their overemphasis on what a few students have criticised as manipulative ‘emotive’ images of people, more often than not young women: ‘Everyone plays on the emotional thing. You get bored of that’ (SD6). This kind of repetitive focus on the female subject is emblematic of what Dogra (2014) describes as the woman/child figure suggesting the natural order, hence obscuring the critical backdrop of history or politics behind a food crisis or poverty-related issue.

So, while it might be disheartening that the key messages about the complex causes or creative solutions possible in relation to poverty are not being clearly communicated, it is reassuring to see that students are to some extent aware of the manipulative and problematic nature of representations of poverty, and the consequent gap in their perception of the issues: ‘If you conform to, kind of, one set of ideas and you don’t, kind of open yourself up to information, em that can be very ... it gives you a very one sided, eh, depiction’ (SD2).

Implications for practice – replication or reform?

Students in this study were clearly aware of the lasting impact of the stereotypical imagery to which they themselves had been exposed in their own schooling, and equally conscious that in many ways, although the dynamic may or may not have changed, the perceptions still prevail:

“I know when I was younger and this is awful to say, but this is just how I, how it was approached with me when I was in school. First of all, I thought Africa was a country, and secondly, … like if they were African-American or if they were dark coloured skin then they were poor, because that’s all I was used to seeing on posters ... So, that’s just something I am very critical of. And it’s the same with all these posters, you know” (SD7).

A study commissioned by Ireland Aid, around the time when this student would have been in second or third class in primary school, showed these kinds of perceptions to be very prevalent. The report found that the most frequent image associations amongst Irish people of the ‘Third World’ were “‘starvation, hunger, no food”; “poverty/no money/babies/children”; “diseases/sickness/blindness”; “suffering/sadness/despair/pain” and “dying people/death’” (Weafer, 2002: 8). Like many of her cohort, the aforementioned student was acutely aware of the impact of similar imagery on her pupils, as well as the need to be equipped to challenge the resulting perceptions: ‘It’s like, it almost puts a stigma. And, and especially when there is a lot of, more diversity now in Ireland, we can’t have that stigma’ (SD7).

On the whole, the students who participated in this study (the majority of whom were student teachers) appear to be aware of the need to prepare themselves for diversity, particularly ethnic diversity in the classroom or workplace, and even at school placement (teaching practice) stage, find themselves having to challenge prevailing practices and perceptions. Two students gave examples of particular difficulties they faced on school placement in relation to challenging stereotypical and outdated imagery in visual aids and textbooks: ‘I actually think that it’s maybe because they’re uncomfortable or maybe because they’re ignorant to it, because that means somebody else doesn’t get represented’ (SD6). Indeed, the equally complex range of reactions to the images depicted shifts from appreciation to helplessness to anger to guilt to discomfort to cynicism at times. It is unclear as to how individuals deal with such emotions and the precise impact such feelings will consequently have on their individual perceptions or actions, whatever about how they share their perceptions through discussion or in their subsequent classroom or work practice.

Several interviewees recounted being stopped in their tracks by particular images and noted the transformative effect those images had on them personally: ‘The pictures that were there [reference to an exhibition of global images during an awareness-raising week in the institute] were of people doing ordinary things. It had an impact on me so I’m now looking at things differently’ (SF4); and ‘Maybe it works [reference to International Women’s Day image display] because it just makes me feel that little bit uncomfortable, you know’ (SF8) and ‘I was thinking about them all day. I was, even when I was talking to anyone, I’d say, did you see the picture like’ (SD4). Equally, the impact of certain images suggested compassion fatigue: ‘Well, that’s happening there, em, it’s terrible and then, when is my next assignment due” (SD2). And ‘If you get bored, you stop listening, em, with the likes of (...) even images like that, the (...) appeal. Like, the likes of that, you know, you’ve seen that so many times, so many times’ (SD6). Strikingly, several interviewees attributed their recently increased awareness of global perspectives and the potential impact on their practice to the very fact of this research: ‘Until you sent out the questionnaire I was oblivious. (...) I wasn’t really aware of what I was doing until you drew my attention to it’ (SF4); ‘Even this research, the fact that it’s going on, will raise my awareness (...) the fact that I’m here this morning, it’s there, it’s (...), in your head, that you’re thinking about it’ (SF5) and ‘Just looking at the pictures and actually sitting down and looking at them, I think it’ll impact my practice more now’ (SD7). Indeed, this may be somewhat reassuring, but as O’Brien, drawing on Cochran-Smith (1991) points out: ‘student teachers need to know that they are part of a larger struggle and that they have a responsibility to reform, not just replicate, standard school practices’ (2009: 198).

Conclusion

This research suggests that higher education students have a much more sophisticated reading of visual images than we might anticipate. In the study their insights and responses challenge the assumptions of the image makers, who it appears, underestimate the critical literacy skills of their audience. In the words of one student interviewee, imagery should ‘ask rather than tell’ (SD8). Carefully created or well-chosen visuals can further critical thinking and provoke deeper questioning. While there is evidently much room for the development of visual literacy knowledge and skills at all stages of primary to higher level education, image producers also need to catch up with their audience by informing themselves and interrogating their approaches. Fundamentally, images of global development need to be produced within a rights-based rather than a charity-based framework, or what Darnton and Kirk refer to as the ‘justice not charity frame’ (2011: 33). Translating this framework to the realm of visual imagery requires on the one hand a rethink of how we depict people and places from the global South, but also a reappraisal of how we should interpret and respond to such images and the situations they highlight. It is time for a radical shift in the visual discourse within the development sector. In the meantime, educators must equip themselves to resist and reform conventional visual approaches.

Note:

This article is drawn from an Irish Aid funded research project which was carried out in a higher education institute in the Republic of Ireland between June 2013 and December 2015. The full research report, including detailed methodology, is available at: www.diceproject.ie/research/papers-reports/

Alam, S (2007) ‘The visual representation of developing countries by developmental agencies and the Western media’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 5, Autumn, pp. 59-65.

Arnold, S (1988) ‘Constrained Crusaders? British charities and development education’, Development Policy Review, Vol. 6, pp. 183-209.

Berger, J (1972) Ways of Seeing, London: Penguin.

Bryan, A and Bracken, M (2011) Learning to Read the World? Teaching and Learning about Global Citizenship and International Development in Post-Primary Schools, Dublin: Irish Aid.

Clark, D J (2004) ‘The production of a contemporary famine image: the image economy, indigenous photographers and the case of Mekanic Philipos’, Journal of International Development, Vol. 16, No. 5, pp. 693-704.

Cochran-Smith, M (1991). ‘Learning to teach against the grain’, Harvard Educational Review ,Vol. 61, No. 3: 279310.

Cochran-Smith, M (2003) ‘Learning and unlearning: the education of teacher educators’, Teaching and Teacher Education Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 5-28.

Cox, A, Herrick, T and Keating, P (2012) ‘Accommodations: staff identity and university space’, Teaching in Higher Education, Vol. 17, No. 6, pp. 697-709.

Darnton, A and Kirk, M (2011) Finding Frames: New ways to Engage the UK public in global poverty, available: http://findingframes.org/report.htm (accessed 8 July 2016).

Dogra, N (2014) Representations of Global Poverty: Aid, Development and International NGOs, London: I.B. Tauris.

Emmison, M, Smith, P and Mayall, M (2012) Researching the Visual (Second Edition), Sage: London.

Escobar, A (1995) Encountering Development: the Making and Unmaking of the Third World, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Gregory, D (1994) Geographical Imaginations, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Honan, A (ed) (2003) Research Report and Seminar Proceedings on The Extent and Effectiveness of Development Education at Primary and Second Level, Dublin: Development Cooperation Ireland.

Humphrys, J (2010) ‘Are Haiti pictures too graphic?’, 25 January, BBC Radio 4 (Today programme), available: http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/today/newsid_8478000/8478314.stm (accessed 8 July 2016).

Jeffers, J (2008) ‘Beyond the image: the intersection of education for development with media literacy’ in M Fiedler and A Pérez Piñán (eds.) Challenging perspectives: teaching globalisation and diversity in the knowledge society, Dublin: DICE Project., available: http://eprints.maynoothuniversity.ie/1231/ (accessed 8 July 2016).

Jenks, C (1995) ‘The centrality of the eye in Western culture’ in C Jenks (ed) Visual Culture, London: Routledge.

Lidchi, H (1999) ‘Finding the Right Image: British Development NGOs and the Regulation of Imagery’, in T Skelton and T Allen (eds.) Culture and Global Change, Routledge: London.

Lissner, J (1977) The Politics of Altruism: A Study of the Political Behaviour of Voluntary Development Agencies, Geneva: Lutheran World Federation, Department of Studies.

Manzo, K (2006) ‘An Extension of Colonialism? Development Education, Images and the Media’, The Development Education Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 9-12.

Manzo, K (2008) ‘Imaging Humanitarianism: NGO Identity and the Iconography of childhood’, Antipode, Vol. 40, No.4, pp. 632-657.

McClintock, A (1995) Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest, New York: Routledge.

Moeller, S D (1999) Compassion fatigue: How the media sell disease, famine, war and death, London: Routledge.

Mudimbe, V Y (1988) The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy and the Order of Knowledge, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Murphy, C (2014) Finding Frames: Exploring Public Communication Materials of Irish NGOs, Dublin: Dóchas.

Nandy, A (1983) The Intimate Enemy: Loss and Recovery of Self under Colonialism, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

O’Brien, J (2009) ‘Institutional racism and anti-racism in teacher education: Perspectives of teacher educators’, Irish Educational Studies, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 193-207.

Pieterse, J N (1992) White on Black: Images of Africa and Blacks in Western Popular Culture, Yale University Press.

Power, C (2012) The Irish Traveller Movement Report on Piloting the Yellow Flag Programme in a Higher Education Institute, Dublin: Froebel College of Education, ITM.

Rose, G (2012) Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials, (3rd Edition), London: Sage.

Said, E (1978) Orientalism, London: Routledge.

Sankore, R (2005) ‘Behind the Image: Poverty and “Development Pornography”’, Pambazuka News, 21 April 2005, available: http://www.pambazuka.org/en/category/features/27815 (accessed 8 July 2016).

Shohat, E and Stam, R (1994) Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media, London: Routledge.

Smith, J (2006) ‘Real World Television’, The Development Education Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 24-25.

Smith, M and Donnelly, J (2004) ‘Power, Inequality, Change and Uncertainty: Viewing The World Through the Development Prism’ in Christopher J Pole (ed) Seeing Is Believing? Approaches to Visual Research: Studies in Qualitative Methodology, Vol. 7, U.K.: University of Leicester.

Sontag, S (1979) On Photography, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Sturken, M and Cartwright, L (2009) Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Suas (2013) National Survey of Third Level Students on Global Development Report, Dublin. available: http://www.suas.ie/sites/default/files/documents/Suas_National_Survey_2013.pdf (accessed 8 July 2016).

Tallon, R and Watson, B (2014) ‘Child Sponsorship as Development Education in the Northern Classroom’ in B Watson and M Clarke (eds.) Child Sponsorship: Exploring Pathways to a Brighter Future, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

VSO (2002) The Live Aid Legacy: The Developing World through British Eyes – A Research Report, London: VSO.

Wambu, O (2006) ‘AFFORD’s experience with the “Aiding & Abetting” project’, The Development Education Journal, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 21-23.

Weafer, J.A (2002) Attitudes Towards Development Co-operation in Ireland: The Report of a National Survey of Irish Adults by MRBI in 2002, Dublin: Ireland Aid.

Young, O (2012) African Images and their impact on Public Perception: What are the Human Rights Implications?, Northern Ireland: Institute for Conflict Research.

Lizzie Downes is a freelance development education practitioner and part-time teacher educator based in Dublin. She has worked in development education for over fifteen years, most recently with the DICE (Development and Intercultural Education) project and previously with the Irish NGO Comhlámh. Her main research interest is the visual representation of global justice and development issues, and she provides specialist training on photographic ethics for civil society organisations and the formal education sector. downes.eliz@gmail.com.