Framing and Contesting the Dominant Global Imaginary of North-South Relations: Identifying and Challenging Socio-Cultural Hierarchies

Reflections and Projections: Policy and Practice Ten Years On

Abstract: In this article, we draw selectively on postcolonial theory to identify problematic patterns of knowledge production and engagement that have historically conditioned a dominant global imaginary grounded on a single story of development and on hierarchies of knowledge, people and forms of organisation that have several implications for encounters between the global ‘North and South’ (1). In the first part of the article we examine perceptions of ‘efficiency’ in educational development partnerships in Zambia. Our data compares insights from two Nordic and three Zambian research participants who worked in Zambia in national level development partnerships in the education sector from 2003 to 2007. In the second part of the article we discuss the need for educational approaches that can shift representations and engagements away from hegemonic, ethnocentric and paternalistic patterns of thinking. In re-thinking education that can support more ethical forms of North-South partnerships, we emphasise the importance of educational strategies that can support people to frame and contest the dominant global imaginary through the development of self-reflexivity in North-South partnerships.

Key words: Education Sector Partnerships; Efficiency; Self-reflexivity; Postcolonial.

We use the term ‘partnership’ in this article with a sense of irony (see also Alasuutari, 2005; Eriksson Baaz, 2005) as we highlight the unequal relations of power at work in international development interventions and collaborations. This uneven playing field is a result of the violent dissemination of a global imaginary based on a dominant single story of progress, development and human evolution that ascribes differentiated value to cultures/countries that are perceived to be ‘behind’ in history and time and cultures/countries perceived to be ‘ahead’ (see for example Andreotti 2011; Bryan, 2008; Eriksson Baaz, 2005; Heron, 2007; McEwan, 2009; Tallon, 2012; Willinsky, 1998). This single story equates economic development with knowledge of universal worth, conceptualises progress as advances in science and technology, and sees those who possess knowledge, science and technology as global leaders who can fix the problems of those who ‘lack’ these traits (see for example Andreotti, 2011; Jefferess, 2008; Spivak, 2004). Therefore, in this global imaginary, humanity is divided between those who perceive themselves as ‘knowledge holders’, ‘hard workers’, ‘world-problem solvers’, ‘right dispensers’, ‘global leaders’; and those who are perceived to be (and often perceive their cultures as) ‘lacking knowledge’, ‘laid back’, ‘problem creators’, ‘aid recipients’ and ‘global followers’ in their journey towards the undisputed goal of development. This global imaginary grounds projects and programmes of international development that mobilise experts and knowledge from the global North, whose knowledge is perceived as knowledge of universal value, to ‘help’ those in the global South, who are perceived to have only culture, traditions, beliefs and values (Andreotti, 2011; Heron, 2007). However, as this article shows, this global imaginary is also internally and externally contested.

Postcolonial theory also makes visible how the accumulation of wealth of ‘more economically developed’ countries in the North, which is perceived to be a result of a superior intellect, better organisation, harder work and more education, has been a result of historical and continuous violence. This violence involves, for example, wrongful resource extraction, land occupation, the infliction of violence through ongoing human exploitation, dispossession and destitution, and the control of the military, of the creation and dissemination of knowledge, of means of production, and of the rules of the game. Postcolonial theory shows that economic poverty heavily subsidises economic wealth. This is an insight that needs to be denied if we want to continue to believe we are benevolent, charitable and innocent people ‘helping the poor’, only fulfilling our manifest destiny of heading humanity towards a future of justice and peace for all.

The main task of postcolonial theory has been to examine and transform this social hierarchy of nations, cultures, and ways of knowing and being (Andreotti, 2006). Postcolonial theory understands the magnitude of the task of changing historical patterns of thinking that ground the wealth and privilege of elites (on both the global North and the South); there are no quick fixes. Conflicting interests, denials, false securities, specific desires for control of processes and outcomes, and perceived entitlements prompt several barriers to the process of learning about one’s complicity in harm through cognition alone (see Kapoor, 2014; Taylor, 2012). Nevertheless, postcolonial theory tries to create vocabularies and questions that, although imperfect, shed light on how the culture, traditions, beliefs, values, and, most importantly, interests of countries in the global North have framed their knowledge, their privilege, and their justification for their mission to intervene, organise, educate and ‘help’ the rest of the world.

In this article, we use these insights to examine how the dominant global imaginary was reproduced and/or contested in a development partnership in the education sector in Zambia and to explore conceptual tools that can open possibilities for ethical solidarities that challenge this global imaginary. In the first part of the article, we focus on the idea of efficiency to explore how Northern and Southern partners expressed or tried to interrupt hierarchies of knowledge, capacity and forms of organisation in their narratives about their work in the Zambian education sector. Postcolonial theory helped us to examine how the dominant global imaginary and its single story of development is imposed, negotiated and/or contested across cultural boundaries. The interviews illustrate how global imaginaries related to development, progress and efficiency were mobilised in the partnership by Southern and Northern partners.

Research overview and methodology

The data we use in this article involves five research participants who worked in the education sector in Zambia. They were part of a national level development partnership that involved multiple countries. The data is part of the doctoral research project of the first author of this article (2). The methodology of this research project, involved questionnaires, interviews and observations in the context of the Zambian education sector from 2003 to 2007. In addition, the first author of the article worked in the Zambian education sector herself for two years (2002-2003). The interviews that were chosen to be used for this article were conducted in 2007 using a narrative research approach and focused on participants’ perceptions of collaboration and partnerships in their work in the Zambian education sector. At this time, the research participants worked either for the Ministry of Education headquartered in Lusaka (both Zambian and non-Zambian research participants) or for the European embassy based in Zambia, Lusaka as a local hire (Zambian) or a diplomat (non-Zambian). The research participants represent both genders (three males and two females). These five research participants were chosen for this article as their narrative interviews were more directly related to perceptions of ‘efficiency’ in North South partnerships that this article discusses. The code of each research participant mentioned after each quotation in this article outlines a number of the research participant, her/his origin (Northern or Southern), whether they work for ‘donor’ (European embassy in Lusaka) or ‘recipient’ (Ministry of Education) and the year of the interview. For example code ‘3ND/2007’ refers to the third research participant coming from a Nordic country who worked for a donor (European embassy in Lusaka) during the time of the interview and was interviewed in 2007.

The historical and political context of the educational sector in Zambia is complex and has suffered from insufficient and declining levels of public expenditure (see Alasuutari and Räsänen, 2007; Banda 2008, Islam and Banda 2011; Musonda 1999). The education sector in Zambia has been dependent on aid since 1975. The sector has been subject of a number of approaches to donor involvement, including project, programme, sector-wide, joint assistance and budget support strategies. Islam and Banda (2011) point out that a Eurocentric orientation that upholds the dominant global imaginary we described before has been prevalent in these approaches. They claim that indigenous (local) knowledges (IKS) in the region have been perceived as a cultural obstacle to the knowledge brought by donors through formal schooling, which is perceived to have universal value (ibid).

The interviews for this article were carried out during the time when there was an attempt for harmonisation of donor practices in the Zambian education sector. In 2004 most of the donor countries signed a memorandum of understanding called ‘Coordination and Harmonization of Donor Practices for Aid Effectiveness’ with the Zambian government. This led to partnerships where most donors were no longer involved in implementing education projects or programmes in the provincial and/or district levels in Zambia. Donors were only involved in national level planning and negotiations with the Ministry of Education. In addition, each donor was no longer supposed to have their own relationship with the Ministry of Education. Instead the donor community chose two lead donors who were given the responsibility to work with the Ministry as representatives of the whole donor community for a period of time. Meetings involving all partners happened only occasionally. This initiative was based on the idea that donors should not be involved with technical and professional support on the ground. The voices and analyses presented in the next section were selected from the dataset because of their focus on perceptions of ‘efficiency’ on both sides.

Ideas of efficiency in North-South partnerships

The interview participants selected for this article could be considered catalysts and translators operating between various communities. They show the complexity of the reproduction and internal contestations of the global imaginary. Their narrative interviews were transcribed, thoroughly read, coded and compared. As the result of the analysis of narratives (see Polkinghore, 1995), themes and categories were created focusing on the perceptions of ‘efficiency’ in North South education sector partnerships. The data illustrates how the global imaginary was reproduced and how it was contested differently by different participants focusing on ideas of efficiency. These ideas reflect the differences between Western rationalism versus the role of a relational (Ubuntu) logic in professional contexts (see Ramose 2003; Venter, 2004). Efficiency was perceived by one side as the capacity to plan, implement and report; while the other side perceived efficiency in terms of the capacity to understand, negotiate, relate and adapt in order to achieve a common goal. While Southern partners were perceived as inefficient within the Western organisational imaginary, Northern partners were perceived as inefficient within the Ubuntu relational imaginary. We first present evidence of reproduction of the dominant global imaginary and then present several examples of Southern partners’ perspectives in response to Northern partners’ perceptions of inefficiency.

A Northern research participant, who worked in one of the European embassies as a diplomat responsible for the national level partnership in the Zambian education sector, expresses a critique towards the Ministry of Education personnel that illustrates the dominant global imaginary:

“The partnership between the donors and the ministry … is not good. I’m fairly critical of it, I’m probably also one of the more critical [parties] here … I think it is not a real partnership actually. I think the ministry is tremendously arrogant, self-righteous, defensive and utterly incompetent. I think the quality of the work they do is miserable … you know we [donors] make it quite clear to them that, the strategic plan expires in the end of the year and it seems to come as a surprise to them that, you know, once it expires you need something new to take its place. It seems to surprise them that they need to come up with a new strategic plan, and you can’t just fund nothing. When you ask for an approval of so and so many millions of dollars, obviously the financial authorities in UK, Ireland or Norway, or anywhere, I imagine, would be asking: ‘Well, what is it that you are funding? … I have almost thrown in the towel, I must admit” (3ND/2007).

The capacity of the Zambian Ministry to spend the funding is also questioned:

“So it is a lot about the mindset basically, I mean they [in the Ministry of Education] have tons of money in this sector, and they are not even able to spend the money what we do provide for them” (3ND/2007).

For this European donor representative it was self-evident that there has to be a strategic framework for any type of implementation:

“I cannot possibly imagine what could be more important for a ministry, any organization basically, than make sure you have got some sort of strategic framework to guide your actions” (3ND/2007).

This reflects the logic of a dominant single story of development and of the universality of the modern Cartesian subject in the dominant global imaginary. The storyline is that we have already agreed on the future we want to have and we just need to engineer this future through objective plans, policies and procedures created and applied by rational individuals. The implication of this logic is that, if individuals do not agree with or understand the storyline, they are at fault: they are perceived as ignorant, disorganised, irrational and/or lacking a ‘proper’ work ethic. By constructing the Other in negative terms, the self is constructed in positive terms (i.e. the participant represents his/her own self-image and culture in opposite terms as intelligent, capable, organised, logical, and hardworking). This participant also rationalised inefficiency in terms of hierarchical conformity, which is perceived to be a feature of a culture ‘behind’ in history, in contrast to his/her culture that is ‘ahead’:

“There is obviously also this very hierarchical society where the idea that you can ask questions or challenge people, challenge powerful people, is still fairly recent thing … It goes back to this fundamental clash between my conception of what I would do if I was in their shoes, and how the world actually looks as seen from their perspective” (3ND/ 2007).

Another Northern partner illustrates this tendency in her/his analysis of why she/he could not make friends easily in Zambia:

“I didn’t realize how much your title makes a difference … I could not make friends, I was lonely. I could only make friends with people around the same level as me. There was a very strict social hierarchy. I think a lot of [it was] brought from the British also … That is also an interesting, strange factor. You see Portuguese influence, you see the British influence, the French influence, and you wonder, after so many years of independence, why you still have cultural influences from the former colony?” (1NR/ 2007).

Zambian participants had complex and sometimes contradictory responses to being framed as ‘behind’ in the global imaginary of development and ‘below’ in the cultural hierarchy of efficiency. Some of the responses projected the same hierarchy within Zambia, while trying to find a solution to the mismatch of expectations and procedures. This reflects the power of the dominant global imaginary in capturing, conditioning and limiting our collective imagination in both the global North and South. Some of these responses are illustrated below. A Zambian participant working for one of the donors in a European embassy in Lusaka criticised the work ethic of Zambians working in the Ministry, blaming Zambian colleagues for what was perceived as a lack of preparation and participation (as opposed to a different type of relationality or other forms of agency, e.g. passive resistance). A view that Zambians are laid back as a result of welfare dependency also denotes class divisions at work in the dominant global imaginary:

“Somebody does not come for a meeting, [and] even if somebody is there for a meeting, they just sit there. Also, if people get documents, they don’t read them, if they come to the meetings, they haven’t read [the documents]. They don’t see that their input is critical … people [in Zambia] grew up thinking, you know I don’t have to play a role … They gave you coupons … actually [people were used to] subsidized food. When there is the element laid-back over and across, the state also compromises the development process. And I [think] more clearly now … I think working from a donor perspective I think work culture is a bit different” (6SD/2007).

On the other hand, the same participant, points out to the inability of Northern partners to analyse the social and cultural processes that matter in the Zambian context.

“It is dynamic, there is a social, cultural process going out there which you have to understand, you don’t just think that you go there with a blueprint and it has to be followed to the letter. You have to balance it, and you have to understand the cultural contexts, differences, and… …It is a give and take. …Sometimes the donors forget it” (6SD/2007).

She/he explains that it is important to understand both perspectives and to find a middle point to be effective in negotiations:

“Of course there are the things that we encounter every day. And they are things that make our lives very difficult in terms of working together. But then also sometimes you find that [there are] some comments, some negative comments also made by the donors, commenting negatively about some of these gaps … It is true that we do have a lot of donors or partners, representatives that go out and because they don’t get what they want, they become very uncompromising … too hard, too pushy, they are too critical. I think you can be critical, but at the same time you have to appreciate the dynamics, because sometimes the people that you are condemning are people that could help [in] that very level … The social, cultural context that they are in is not facilitating, because it is not one person, it is endemic, it is systematic, and it is built-in … so you need people. You need to understand that. But you see, they [donors] don’t understand that, it is a question of understanding the two perspectives. If you don’t find the middle point, you have a problem … you need to understand each other within context” (6SD/2007).

Another Zambian research participant illustrates the need for better cultural understanding with reference to the purpose and use of technical reports in both contexts.

“We have had a number of technical advisors who have come in sat on their own, written reports, but then the reports have not reached anywhere because there has not been that mixing, and ensuring that the other people also understand the same problems they are trying to raise” (2SR/2007).

‘Ubuntu’ was also identified as a grounding aspect of working relationships that Northern partners have difficulties to understand and relate to:

“what really drives an African person for example … is …‘Ubuntu’. Ubuntu is that inner thing in an African context that links them up to the other person, to this social group. So, you have to be appreciated as a humane person. So in that context this also compromises accountability, because you don’t demand so much from your work mates. Because at the end of the day it is a humane person (in you) that should be more prominent. For example, if there is a disciplinary action taken, you very, very rarely will see that disciplinary action taken, because the other considerations that will be made, you know … that person has a large family, he’s looking after his mother. You know, what was seen as ‘Ubuntu’, that kind of human nature. It is really, in the old, in the traditional African setting … it is also a family system, you have to look after your kin, your brother. If your neighbor’s mother died, your obligation is to make sure that you attend to your neighbor, attend to him. But then that means that you have to miss work. If you have a company car, for example, it is your obligation to avail that care to your brother, who is in trouble. So what is yours is mine, even from a company perspective or from a ministry perspective, that certain facilities and resources available for the particular officer, it is also available for the group … There is [sic] some of these hidden elements, even things like contracts for example, the way we understand our contractual examples might not be the same as the understanding of contractual obligations within the African context” (6SD/2007).

This participant suggests that being aware of the differences in perspective might help Northern and Southern colleagues improve productivity:

“Of course there is no ‘black and white’, there is no right way. I think it’s just an awareness process that, look, there are certain things that may not be very obvious that are hidden in your partnership [which] proves that you need to be a bit more conscious of. And also the effect of this on the system: how it can impact productivity” (6SD/2007).

It was also pointed out that non-Zambians are not always capable of negotiating towards a compromise and connecting with other colleagues:

“People tend to come with very strong ideas [and think that] this must be done this way, nothing else. But if you are a good negotiator, you let people to see value, the merits … and then find a middle point” (2SR/2007).

This Zambian research participant outlined that donors were not always capable of understanding reasons for some delays and therefore started to mistrust Zambian professionals:

“There is … mistrust. For somebody to entrust you with so much financial resources … you need to be able to account for them properly. And that, I think, taught us the lesson that we [in the Ministry of Education] need to ensure that the human resource is properly trained” (2SR/2007).

The same participant pointed out that there was also mistrust at a number of levels other than financial accountability:

“The cooperating partners [donors] wanted to ensure that services, goods and infrastructure [that they were funding] are procured within agreed timetable. And, because of the lack of capacity by the Ministry, it has lagged behind on a number of procurement issues. [When] books have not reached schools, the donors come up and say: look, we gave you the money but why are books not in school? Classrooms have not been finished on time and donors have come up and said but look, we gave you the money to build classrooms, but where are these things…” (2SR/2007).

In addition, she/he highlighted that for a long time the donors were not capable of understanding that they should not impose ‘donor programmes’:

“From the BESSIP [Basic Education Sub-sector Program] days, up to the current situation, one may admittedly say: yes, donors have also got their own agenda, but they also want the agenda to fit in with the national development programs … There have actually been accusations … [colleagues in the Ministry claimed that] its’ the donors [who] want that, for moving to this direction, we [Ministry] want to move to this particular direction. But what we [donors and Ministry of Education] failed to understand is to meet on one table, plan and be able to carry on with our work. Later on we instituted a system where we had joined committees” (2SR/2007).

Another Zambian research participant, who worked as a local hire in one of the European embassies in Lusaka during the time of the interviews, expressed that she/he positioned her/himself as working ‘in between’ the donor and recipient communities for example when attending to the meetings that were organised with Ministry of Education officials and donor representatives. She/he expressed that her/his non-Zambian colleagues were not capable of understanding when ‘yes’ meant ‘no’. In addition s/he questioned if her/his donor colleagues were committed to seeing and supporting change away from aid dependency (see also McCloskey, 2012).

“I see the difference in how they relate to other cultures that are outside of their own in the workplace … sometimes I’m sitting in a meeting, and I can tell when no means a yes and a yes means no, but I look around and I see that my [donor] colleagues are actually convinced that the yes means yes. But you know I am able to read the language on both sides at least to assess the language in both sides. And it’s interesting to watch, and it also starts to get you to question, you know, whether there will ever be an end to development, and whether development is a feel good [theme] or whether there is any commitment on the part of the donors actually to see change” (4SD/2007).

The same research participant suggested that donors are not capable of fighting against unevenness:

“In Africa, development is seen as something that is donor driven and not people driven. We talk of democracy, the donors are happy [that] there is a democracy, but they don’t see anybody pushing the government. So in other ways, they [donors] are supporting mediocrity in our country [Zambia], but they [donors] don’t support the same [mediocrity] in their country … So in other words, they are saying we are mediocre … we should be thankful even for these minimal standards. And they think this money will help Zambia, but at the end of the day, what does it mean? … It is almost another form of colonization, only it’s much nicer, you know, and if you are blinking, you didn’t even notice it, but that’s basically what it is” (4SD/2007).

Our final quote shows a Zambian research participant narrative about how consensus was reached after working through conflict:

“We decided to do a joint approach to develop Ministry of Education’s … plan. We set up a team made up of the co-operating partners [donors] … and the Ministry to of Education. And, we set up a road map, this is how it should be done, agreed, agreed and we started doing the work. We visited the various school districts, did SWOT analysis before building up the case, what programs should be in-built into this. But in the process I think the team just got exhausted. I remember very well, we were in the hotel [working] … the team couldn’t simply come to work and couldn’t continue any longer … we were about to present it to joint committee for approval, and then there was a breakdown within the group. Words were being exchanged between various parties which were bordering on personal challenges … Somehow I just got courage and [stood] to the group, I said ‘gentlemen and ladies, please, look where we have come from and where we are going. I think dawn is nearby, and if we continue in this fashion, all our efforts will be wasted’. That was a turning moment, everybody simply stopped working and we sat for a while and reconciled our differences. Within a week a document that we are still using was presented and approved. I think to me it showed the spirit of working together. But even in the spirit of working together, you should be prepared for differences. But what could be worse is, if you don’t resolve the differences, then you are gone” (2SR/2007).

The responses from Southern partners presented above point towards the need for the development of trust and flexibility, which requires an ability to imagine and to work at the edge of the normalised global imaginary grounded in hegemonic and ethnocentric perceptions of ends and means of development and on hierarchies of the value of knowledge, people and forms of organisation. However, if one has been socialised into believing in the superiority of one’s culture and in the universality of one’s knowledge, it becomes very difficult to see the value of working at the edge of this imaginary, rather than its centre. Spivak talks about this as the loss embedded in one’s privilege (of being placed at the centre of the world). In order to work with ways of knowing and being that have been historically marginalised or rendered irrelevant in the dominant global imaginary, one has to ‘de-center’. De-centering involves learning the origins and limits of one’s way of thinking, divesting from the benefits one has acquired in inhabiting the centre, and learning to listen and to learn from/with ‘Others’ (who have historically been framed as lacking). We turn to this process of learning and unlearning next.

Learning to listen and to learn at the edge of one’s knowledge

The historical centering of the Cartesian subject (represented by Northern partners) as the agent of ‘development’ in the dominant global imaginary creates problematic forms of representations and engagements between partners in the North and in the South. Some of these forms of representation are listed and explained in the HEADS UP checklist (Andreotti, 2012) which we explore in more detail in the next section. This section is concerned with how we can encourage those who have been historically educated to inhabit the centre of the global imaginary to learn to listen and to learn at the edge of one’s knowledge.

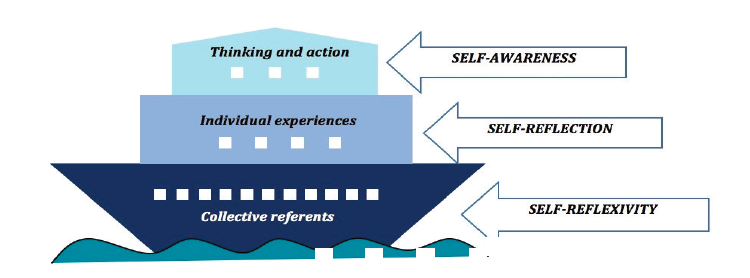

We propose that self-reflexivity is a good starting point for understanding the limits of universalised forms of knowing. We make a strategic distinction between reflection and reflexivity to illustrate our point. Reflection aims at thinking about individual choices and journeys at the centre of the global imaginary. Self-reflexivity aims at understanding the limits of the frames of reference that condition and restrict our choices (of being and knowing) within the dominant global imaginary. Self-reflexivity traces individual expectations and assumptions to collective socially, culturally and historically situated ‘stories’ with explicit ontological and epistemological assumptions that define what is real, ideal and knowable. Figure 1 (modified from Andreotti, 2006, 2014) below illustrates the strategic differences we propose between awareness, reflection and reflexivity.

The top level of the three-leveled boat demonstrates thinking and action as the most surface level of the boat that is also most visible. ‘Cartesian’ understanding of subjects states that we can say what we think and describe accurately and objectively what we do (Andreotti, 2006). Hence, it is important to point out, that our ability to describe our thoughts is limited to what can be said; what is proper and intelligible to both us and to others. There are things that are not suitable to say in some contexts and there are issues that we think or do that we cannot explain or even acknowledge. Our capacity to describe what we do is limited by what we can notice and by what we want to present to others. From this perspective, self-awareness involves a recognition of the limits of language in describing ourselves and the world.

Figure 1. Self-reflexivity, self-reflection and self-awareness

Individual experiences are explored in the second level of the boat. This level recognises that what we say, think and do are based on our individual journeys in various contexts. These journeys are rooted in our ordinary, inspiring or traumatic learning experiences and concepts, and dependent upon what we have been exposed to. The analysis of the second level could be named as ‘self-reflection’ (see also Mezirow, 1991, 1996; Taylor, 2004). This level also recognises and considers individual investments and desires that can be conscious or unconscious, rooted in passions, traumas or other affective and/or emotional needs.

The third level of the boat recognises that our experiences and the very analyses of these experiences are conditioned by collective referents grounded on the languages and understandings we have inherited to make sense of reality and communicate with others (Andreotti, 2006). There are specific criteria for what counts as real and ideal (ontology) and what can be known and how (epistemology), and how to achieve what is considered good (methodology) in various contexts. These criteria are collective and socially, culturally and historically ‘situated’ as they depend on a group’s social, cultural and historical background. The change with this level is slow as contexts change and criteria of different groups interconnects and also contradict each other. Diversity within a group of same criteria will always be there and the process is never static. However, there is a dominant set of criteria that represents the ‘common sense’ of a group or groups. The analysis of the third level can be considered self-reflexivity.

The boat encourages people to notice that individual thinking and individual choices are never completely ‘free’, ‘neutral’, or only ‘individual’ as the things we say, think and do are conditioned (but not necessary determined) by our contexts (see Andreotti, 2010a, 2010b). The assumption of the self-evident subjects – the idea that there is a direct correlation between what we say, what we think and what we do – is also challenged by self-reflexivity. Self-reflexivity offers a way to understand the complex constitution of subjectivities, the interdependence of knowledge and power, and of what is sub- or un-conscious in our relationships with the world (see Andreotti, 2014; Kapoor, 2004; McEwan, 2009).

Many scholars (such as Eriksson Baaz, 2005; Wang, 2009) argue that engaging with different ‘Others’ supports critical self-understanding, but exposure in itself is not enough. Wang points out that ‘the transformation of subjectivity cannot happen without going back to unsettle the site of the self’ (2009: 174). Very often intercultural learning aims to promote ‘openness’ without unsettling the self, without engaging with racial hierarchies, historical power relations or the collective frames that condition our possibilities of understanding. This kind of ‘openness’ is only open to that which does not unsettle or de-centre the self. In this case, while the self sees itself as really open, racialised others who challenge one’s self-image can be kept safely at a distance and objectified (Wang, 2009). This is often the case in North-South partnerships. One can only be interested in creating knowledge about others, but not willing to pursue the endeavour of self-awareness, self-reflection or self-reflexivity. In this case, the privileged site of the centered self is left untouched. When the self is not unsettled, the modern desires of mastery and control, and the desires underlying racial, gendered, and class hierarchies both historically and contemporarily are left unquestioned (ibid).

It is important to acknowledge that it is theoretically contradictory to expect a clear set of normative values or ethical principles from a postcolonial critique where the benevolence of every attempt to ‘make things better‘ is a suspicion of reproducing unexamined colonial practices (Andreotti, 2014). However, it is precisely this doubt of the benevolence of benevolence (see Jefferess, 2008) that can create the possibility of self-reflexivity, humility and openness that are foundations for ethical forms of solidarity ‘before will’ (Andreotti, 2014; Spivak, 2004). On the other hand, it is important that in this process the historical imbalances related to distribution of resources and knowledge production are not forgotten but kept confidently on the table. There is a set of ethical practices that postcolonial theory suggests. These ethical practices propose that it is impossible to turn our back to difficult issues such as our complicity in systemic harm, the perseverance of relations of dominance, contradictions and complicities of crossing borders, the inconsistencies between what we say and what we do, or our own sanctioned ignorance (Andreotti, 2014).

The pedagogical framework for learning of the project ‘Through Other Eyes’ (see Andreotti and de Souza 2008) inspired by Spivak (1999) proposed four approaches of learning when aiming towards ethical engagement in North-South encounters and ethical relations with the Other (see also Andreotti, 2011; Andreotti & de Souza, 2008; Biesta & Allan & Edwards, 2011; de Souza & Andreotti, 2009; Kapoor, 2004; 2014; McEwan, 2009). This pedagogical framework, which has been tested and developed further, can support those over-socialised in the dominant global imaginary to learn to unlearn, to listen, to be taught and to reach out when aiming at working without guarantees.

Drawing on Spivak, Kapoor argues that the aim of ‘learning to unlearn’ should be to ‘retrace the history and itinerary of one’s prejudices and learned habits, stop thinking of oneself as better or fitter, and unlearn dominant systems of knowledge and representation’ (2004: 641). It also involves ‘stopping oneself from always wanting to correct, teach, theorize, develop, colonize, appropriate, use, record, inscribe, enlighten’ (ibid: 642). Unlearning is about reconsidering and reassessing those positions that were previously thought to be both normal and self-evident (see also Andreotti, 2007; McEwan, 2009; Moore-Gilbert, 1997). Unlearning can help us identify and rearrange the allocation of modern desires that place modern subjects at the centre of the world, such as the desire for seamless progress in linear time that guarantees our ‘futurity’, the desire for agency grounded on innocent protagonism (e.g. feeling, looking and doing ‘good’) and the desire for comprehensive knowledge that can secure our certainties, comforts and control (Andreotti, 2014).

The second and third approaches of learning are ‘learning to listen and to be taught’. This idea aims at learning to perceive the effects and limitations of one’s perspective and acquire new conceptual models (Andreotti and de Souza, 2008). In terms of ethical encounters, learning to listen and to be taught requires the self to be interrupted by receiving a gift that it cannot expect (Biesta, 2004; Bruce, 2013). Biesta (2012) outlines a distinction between the idea of ‘learning from’ the Other and that of ‘being taught by Other’. Learning from the Other may occur without alteration to our unified idea of the self. It is this learning from the Other without alteration that might be essentially a liberal humanist project of self-betterment (Heron, 2007; Kirby, 2009; Bruce, 2013). However, when we say that ‘this person has really taught me something’ (Biesta, 2004), we imply that we have been altered unexpectedly by this transcendent encounter and comes as a revelation.

In intercultural education, it is common to see the importance of openness emphasised. However, the modern Cartesian subject can only be open to that which he/she can ‘understand’ within its own terms of reference. His/her limited way of knowing is perceived as unlimited and forecloses possibilities outside of his/her own comprehension creating a vicious circle where by insisting on and affirming its (superficial) openness the Cartesian subject in fact performs closure. In other words, if you believe you are open, you probably have not reached the edges and limits of your knowing. Self-reflexivity creates a healthy suspicion of the ways we listen, helping people observe themselves listening, and asking questions such as: what is framing my understanding and interpretation? How are my referents ‘coding’ what I am hearing into what is convenient for me? How could this other voice be saying something completely different from what I can understand?

In terms of pluralising referents of reality in North-South encounters, the single story of development and the protagonism of both Northern and Southern subjects within it need to be examined if ‘listening’ and ‘being taught’ are to take place. Key questions include: Whose development are we talking about? Who decides? In whose name? For whose benefit? How come? What ontological (and metaphysical) referents ground the dominant idea of development? What are the hidden dimensions and implications of this ideal? How could development be thought through other referents? Within a different constellation of referents (e.g. non-anthropocentric, non-Cartesian), would chronological and teleological development make any sense? This involves ‘[a suspension of belief] that I am indispensable, better, or culturally superior; it is refraining from always thinking that the Third World is “in trouble” and that I have the solutions; it is resisting the temptation of projecting myself or my world onto the Other’ (Spivak 2002: 6; Kapoor, 2004: 642).

The fourth approach of learning is ‘learning to reach out when aiming to work without guarantees’. This does not only mean that one is aware of the blind spots of one’s power and representational systems, but it also requires the ability to apply, adapt, situate and re-arrange this learning to one’s own context; to be able to put one’s learning into practice. Working without guarantees demands being open to unexpected responses and that failure is seen as success (ibid: 644). Moore-Gilbert outlines that failure can also be viewed as a possibility to create ‘constructive questions and corrective doubts’ (cited in Andreotti, 2007: 74). In the tight time schedules of many development aid projects failure might not be easily accepted which might lead to quick, often one-sided solutions. Courage for admitting ‘not knowing’ is not always visible or desirable in this context. For development professionals it means being open to the limits of knowledge systems (see Banda, 2008) and also of the profession: ‘enabling the subaltern while working ourselves out of jobs’ (Kapoor, 2004: 644) which could be a different and perhaps more sustainable approach for development aid/development activities. This approach might require moving beyond modern teleologies of progress and outcome oriented success as well as innocent heroic protagonism and totalising forms of knowledge production about Self and Other and the world.

Conclusion: different questions to think with

In re-thinking education that can support more ethical forms of North-South partnerships, we emphasise the importance of educational strategies that can equip people to question the dominant single story of development, and to develop self-reflexivity, an awareness of the politics and historicity of knowledge production, a willingness to share authorship and ownership of goals, processes and outcomes, and a relational imperative to trust and take risks in learning to work without guarantees. HEADS UP is a pedagogical tool that provides one framework for developing these dispositions in North South partnerships. This tool has been used in analysing community engagement and development projects across a range of settings, NGO, and volunteer work (Andreotti, 2012; Bruce, 2014). Therefore we felt it would be useful to conclude this article with something that practitioners could think with. The modified version of the HEADS UP checklist below (see Table 1) illustrates the kinds of questions that could be asked in the process of supporting Northern development workers to interrupt problematic patterns of representation and engagement with Southern communities (see Islam & Banda, 2011). It also exemplifies what is involved in the process of learning to unlearn, to learn to listen, to learn to be taught, and to learn to reach out without guarantees. We hope it will help practitioners create the spaces and vocabularies to interrupt and transform problematic historical patterns of relationships in their contexts.

Table 1. HEADS UP ‘Purposes of education’

Notes

(1) In this article, we made a decision to use the terms ‘global North’ and ‘global South’ to refer to nations and cultures that are ‘scripted’ as more or less economically developed. We recognise that cultures and nations, as well as the development story, are social constructions that are also contested. We acknowledge that social hierarchies are multiple within cultures (e.g. gender, class, race, ethnicity, ability, merit, etc.), which adds a layer of complexity to the idea of a homogeneous global ‘North’ and ‘South’ (i.e. there are elites and subjugated peoples in both North and South). However, for the socio-cultural hierarchy we target in this article, this construction, albeit problematic, is still extremely useful for the sake of focus and clarity.

(2) As a researcher, she acknowledges that as a white, Northern, European, Finnish-born academic, she embodies epistemological dominance and cannot be positioned as neutral or objective in her analyses (Schick and St. Denis, 2005; Taylor, 2012). However her experiences as a wife of a Somali husband and of raising mixed-heritage children give her further insight into the dynamics of the construction of privilege. These insights connect her motivations and research to her lived realities. The second author of the article is her doctoral research supervisor and a Canada Research Chair in Race, Inequalities and Global Change at the Department of Educational Studies, University of British Columbia, in Vancouver.

References

Alasuutari, H (2005) ‘Partnership and its conditions in development co-operation’ in R Räsänen and J San (eds.) Conditions for Intercultural Learning and Cooperation, Turku: Finnish Educational Research Association.

Alasuutari, H and Räsänen R (2007) ‘Partnership and ownership in the context of education sector programs in Zambia’ in T Takala (ed.) Education sector programs in developing countries – socio-political and cultural perspectives, Tampere: Tampere University Press.

Andreotti, V (2006) ‘Soft versus critical global citizenship education’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 3, Autumn, pp.40-51.

Andreotti, V (2007) ‘An ethical engagement with the Other: Gayatri Spivak on education’, Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices, Vol.1, No.1, pp. 69-79.

Andreotti, V (2010a) ‘Global Education in the 21st Century: two different perspectives on the “post-” of postmodernism’, International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 5-22.

Andreotti, V (2010b) ‘Glimpses of a postcolonial and post-critical global citizenship education’ in G Elliot, C Fourali and S Issler (eds.) Education for Social change, London: Continuum.

Andreotti, V (2011) Actionable postcolonial theory in education, New York, NY: Palgrave MacMillan.

Andreotti, V (2012) ‘Editor’s preface HEADS UP’, Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices Vol. 6, No. 1.

Andreotti, V (2014) ‘Critical literacy: Theories and practices in development education’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 19, Autumn, pp. 12-32.

Andreotti, V and de Souza, L (2008) ‘Global Education: four tools for discussion’, Journal of Development Education Research and Global Education, Vol. 31, pp. 7-12.

Banda, D (2008) Educational For All (EFA) and the African Indigenous Knowledge Systems (AIKS): The case of the Chewa people of Zambia, Bonn: Lambert Publishing Company.

Biesta, G (2012) ‘Receiving the gift of teaching: From learning from to being taught by’, Studies in Philosophy and Education, online first.

Biesta, G (2004) ‘The community of those who have nothing in common: Education and the language of responsibility’, Interchange, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 307–324.

Biesta, G and Allan & Edwards (2011) ‘The theory question in research capacity building in education: Towards an agenda for research and practice’, British Journal of Educational Studies, Vol. 59, No. 3, pp. 225-239.

Bruce, J (2013) ‘Service Learning as a Pedagogy of Interruption’, International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, Vol. 5, No.1, pp. 33-47.

Bruce, J (2014) Framing Ethical Relationality in Teacher Education: Possibilities and challenges for global citizenship and service-learning in the physical education curriculum in Aotearoa/New Zealand, Christchurch: University of Canterbury.

Bryan, A (2008) ‘Researching, and searching for international development in the formal curriculum: Towards a post-colonial conceptual framework’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 7, Autumn, pp. 62-79.

de Souza, L and Andreotti, V (2009) ‘Culturalism, difference and pedagogy: lessons from indigenous education in Brazil’ in J Lavia and M Moore (eds.) Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Policy and Practice: Decolonizing Community Contexts, London: Routledge.

Eriksson Baaz, M (2005) The Paternalism of Partnership: A Postcolonial Reading of Identity in Development Aid, London: Zed Books.

Heron, B (2007) Desire for development: Whiteness, gender, and the helping imperative, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Islam, M R & Banda, D (2011) ‘Cross-Cultural Social Research with Indigenous Knowledge (IK): Some Dilemmas and Lessons’, Journal of Social Research & Policy, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 1-16.

Jefferess, D (2008) ‘Global citizenship and the cultural politics of benevolence’, Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 27–36.

Kapoor, I (2004) ‘Hyper-self-reflexive development? Spivak on representing the Third World “Other’”, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 4, No. 25, pp. 627-647.

Kapoor, I (2014) ‘Psychoanalysis and development: contributions, examples, limits’, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 35, No. 7, pp. 1120-1143.

Kirby, K E (2009) ‘Encountering and understanding suffering: The need for service learning in ethical education’, Teaching Philosophy, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 153-76.

McCloskey, S (2012) ‘Aid, NGOs and the Development Sector: Is it time for a new direction?’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 15, Autumn, pp. 113-121.

McEwan, C (2009) Postcolonialism and Development, London: Routledge.

Mezirow, J (1991) Transformative dimensions of adult learning, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mezirow, J (1996) ‘Contemporary paradigms of learning’, Adult Education Quarterly, Vol. 46, No. 3, pp. 158-172.

Moore-Gilbert, B (1997) Postcolonial Theory: Contexts, Practices, Politics, London: Verso.

Musonda, L (1999) ‘Teacher education reform in Zambia … is it a case of a square peg in a round hole?’, Teaching and Teacher Education, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 157-168.

Polkinghorne, D (1995) ‘Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis’ in J Hatch & R Wisniewski (eds.) Life, history and narrative, London: Falmer Press.

Ramose, M B (2003) ‘The Philosophy of Ubuntu and Ubuntu as Philosophy’ in P H Coetzee and A P J Roux (eds.) The African Philosophy Reader, New York: Routledge.

Schick, C and St. Denis, V (2005) ‘Critical Autobiography in Integrative Anti-Racist Pedagogy’ in C L Biggs and P J Downe (eds.) Gendered Intersections: A collection of Readings for Women’s and Gender Studies, Halifax: Fernwood.

Spivak, G (1999) A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a Critique of the Vanishing Present, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Spivak, G (2004) ‘Righting wrongs’, The South Atlantic Quarterly, Vol. 103, pp. 523-581.

Tallon, R (2012) ‘The Impressions Left Behind by NGO Messages Concerning the Developing World’, Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 15, Autumn 2012, pp. 8-27.

Taylor, E W (1994) ‘A Learning Model for Becoming Interculturally Competent’, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Vol. 18, pp. 389-408.

Taylor, E W (2009) Transformative learning in action: A handbook for practice, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Taylor, L (2012) ‘Beyond Paternalism: Global Education with Preservice Teachers as a Practice of Implication’ in V Andreotti and L M de Souza (eds.) Postcolonial perspectives on global citizenship education, New York, NY: Routledge.

Venter, E (2004) ‘The notion of Ubuntu and communalism in African educational discourse’, Studies in Philosophy and Education, Vol. 23, pp. 149-160.

Wang, H (2009) ‘Pedagogical Reflection V: Self-Understanding and Engaging Others’ in H Wang and N Olson (eds.) A journey to unlearn and learn in multicultural education, New York : Peter Lang.

Willinsky, J (1998) Learning to Divide the World: Education at Empire’s End, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hanna Alasuutari is a doctoral student at the Faculty of Education in the University of Oulu, Finland where she has also worked as researcher and teacher trainer for five years. She has extensive work experience in the field of education sector partnerships and has worked with education sector development and education reform initiatives in various contexts such as Zambia, Ethiopia, Montenegro and United Arab Emirates. Her academic work concentrates on examining educational approaches for addressing problematic patterns of international engagements in the areas of international education sector partnerships, global- and development education.

Vanessa de Oliveira Andreotti is Canada Research Chair in Race, Inequalities and Global Change, at the Department of Educational Studies, University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. She has extensive experience working across sectors internationally in areas of education related to international development, global citizenship, indigeneity and social accountability. Her work combines poststructuralist and postcolonial concerns in examining educational discourses and designing viable pedagogical pathways to address problematic patterns of international engagements, flows and representations of inequality and difference in education. Many of her publications are available at: https://ubc.academia.edu/VanessadeOliveiraAndreotti.