Hope and Hopelessness in the Face of a Polycrisis

Development Education and Hope

Abstract: In light of ever increasing global challenges, the need for hope has never been greater, the need for action has never been more acute and the need for critical, transformative education is now absolutely essential (Dolan, 2024). The concept of ‘polycrisis’ can be debilitating and disempowering. The idea of multiple, interconnected crises can be overwhelming and lead to feelings of helplessness, anxiety, and a sense of being unable to cope with the challenges facing the world. This article argues that global citizenship education (GCE) should acknowledge the challenges of polycrisis while also emphasising agency, collaboration, and positive action, thus helping learners to navigate this complex era without succumbing to debilitating feelings of despair.

Key words: Polycrisis; Hope; Transformative Global Citizenship Education.

Introduction

2025 marks the eightieth anniversary since the United States (US) dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, and the second on Nagasaki three days later. About 214,000 people were killed in the blasts and Japan surrendered on 15 August 1945 (Selden and Selden, 1990). The phrase ‘never again’ after the Second World War and the establishment of the United Nations (UN) signified a global commitment to prevent future atrocities such as the Holocaust. The UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights were created to enshrine principles of sovereignty, political independence, and equal dignity, aiming to protect future generations from the scourge of war. Specifically, the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (UN, 1948) was created to classify and prevent genocide. Deplorably and to our shame, the ongoing genocide in Gaza (Amnesty International, 2024), including the dire humanitarian situation and the impact on civilians, highlights the failure of the United Nations and the limitations of global citizenship in promoting peace, justice, global solidarity and compassion. In Gaza, starvation is being used as a weapon of war and genocide as the health system, run by hungry and exhausted health workers, cannot cope. Genocide in Gaza is an international crisis occurring in the context of multiple crises collectively referred to as a polycrisis. The situation in Gaza serves as a stark reminder of the limitations of global citizenship education (GCE) in its current form. It highlights the need to strengthen educational approaches that foster critical thinking, empathy, a commitment to human rights, and a willingness to take meaningful action to address injustice and conflict.

In this article, I explore the polycrisis as a context in which GCE operates. I argue that GCE needs to return to its radical roots in order to address the polycrisis in all its complexity. I also suggest that GCE needs to adopt a more transformative approach underpinned by radical, political and active forms of hope to inspire action and agency and to overturn widespread levels of individual, societal and political complacency. GCE (or global education) is essentially a hopeful endeavour. The Dublin Declaration, also known as the European Declaration on Global Education to 2050, is a strategy framework designed to strengthen and improve GCE across Europe. According to the Dublin Declaration, global education ‘empowers people to understand, imagine, hope and act to bring about a world of social and climate justice, peace, solidarity, equity and equality, planetary sustainability, and international understanding’ (GENE, 2022: 3). GCE encourages learners to critically analyse global issues while maintaining a sense of hope for a more just and equitable world. Hope plays a crucial role in fostering agency, action and solidarity for a better future. Hopelessness on the other hand can generate feelings of powerlessness, low self-esteem, depression and anxiety. We are living in uncertain times whereby various crises – economic, environmental and geopolitical – interact and amplify each other creating what is known as a polycrisis. The confluence of destabilising planetary pressures with growing inequalities, together with the devastating genocide in Gaza and the silent complicity which accompanies it, present new, complex, interacting sources of uncertainty for the world and everyone in it. This can further exacerbate feelings of hopelessness, powerlessness, sadness, anger, fear and instability.

This article argues that GCE should acknowledge the challenges of the polycrisis while also emphasising agency, collaboration, and positive action, thus helping learners to navigate this complex era without succumbing to debilitating feelings of despair. I explore pedagogies of hope in the context of a global polycrisis. Pedagogies of hope have been developed by critical educational theorists such as Freire (2004) and hooks (2003), who connect hope with individual and collective transformation. As hooks suggests: ‘to successfully do the work of unlearning domination, a democratic educator has to cultivate a spirit of hopefulness about the capacity of individuals to change (hooks, 2003: 73). As an initial step, GCE needs to recognise and address the complexity of the polycrisis.

The polycrisis

The interaction of complex geopolitical threats has led to the emergence of a ‘polycrisis’, a complex situation where multiple interconnected crises converge and amplify each other resulting in a scenario which is difficult to manage or resolve. The concept of ‘polycrisis’ can be debilitating and disempowering. The idea of multiple, interconnected crises can be overwhelming and lead to feelings of helplessness, anxiety, and a sense of being unable to cope with the challenges facing the world. The term itself has been conceptualised in various ways in the literature. For instance, Roubini (2022) uses the term ‘megathreats’ where multiple crises are interlinked, intensify each other and resist simple solutions. Today, the polycrisis constitutes numerous challenges including conflict, genocide, migration, inflation and authoritarianism. Energy and food prices are spiking, accelerated by the current and longer-term threats of climate extremes, biodiversity loss and rising inequality. These are further exacerbated by the economic and existential threat of Artificial Intelligence (AI), the chilling rise of far-right populism, and heightening geopolitical tensions. Chasing endless growth on a finite planet is having multiple and interconnected consequences. Indeed, our current rates of consumption can only be sustained if we have a minimum of 1.5 planets (Kitzes et al., 2008), which means we are rapidly eating into our natural capital and depleting the Earth’s resources. Cracks in existing economic and social systems are ever apparent while ‘the different axes of crisis are interacting and reinforcing one another so the whole is worse than the sum of the parts’ (Norton and Greenfield, 2023: 7).

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (2023) states that the world’s temperature will exceed 1.5°C in the course of this century, with serious implications for human societies and natural systems everywhere. Climate injustice ensures that those least responsible bear the greatest impact. Meanwhile, the global inequality gap continues to grow. Oxfam's 2025 report, Takers Not Makers: The Unjust Poverty and Unearned Wealth of Colonialism, highlights the accelerating concentration of wealth among the global elite, revealing systemic inequalities rooted in historical and contemporary exploitation (Taneja et al., 2025). While the number of billionaires continue to grow, the number of people living in poverty has barely changed since 1990 due to the intersecting impacts of economics, climate and conflict. The World Inequality Report 2022 found that the top 10 percent of the world’s population hold 76 percent of global wealth, while the bottom 50 percent hold 2 percent (Chancel et al., 2022). Inequality matters. Inequality damages everyone not just the poor. Yet, policies which address inequality through social welfare and increased taxation benefit entire societies. Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett’s (2009) groundbreaking book The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better argues that societies with less income inequality experience better outcomes across a wide range of social and health indicators not just for the poor, but for everyone.

Biodiversity (or the variety of all life on earth) sustains human life and underpins our societies. Yet, the rate of extinction of species in the last one hundred years, which has rapidly accelerated in recent decades as we destroy ecosystems for economic growth, is higher than those in most of the previous mass extinction events. The latest edition of the Living Planet Report (WWF, 2024), which measures the average change in population sizes of more than 5,000 vertebrate species, shows a decline of 73 percent between 1970 and 2020. Extinction rates are even more severe for insects, a situation exacerbated by habitat loss, pesticide use, pollution and climate change. Changes in the natural world may appear small and gradual but over time, their cumulative impacts can add up to trigger a much larger change. Such tipping points can be sudden, often irreversible, and potentially catastrophic for people and nature. The opportunities for tipping points, magnify due to interacting spurs within a polycrisis. Ecological, technological and social systems are highly connected and highly homogeneous thus rendering them susceptible to the domino effect of cascading failures.

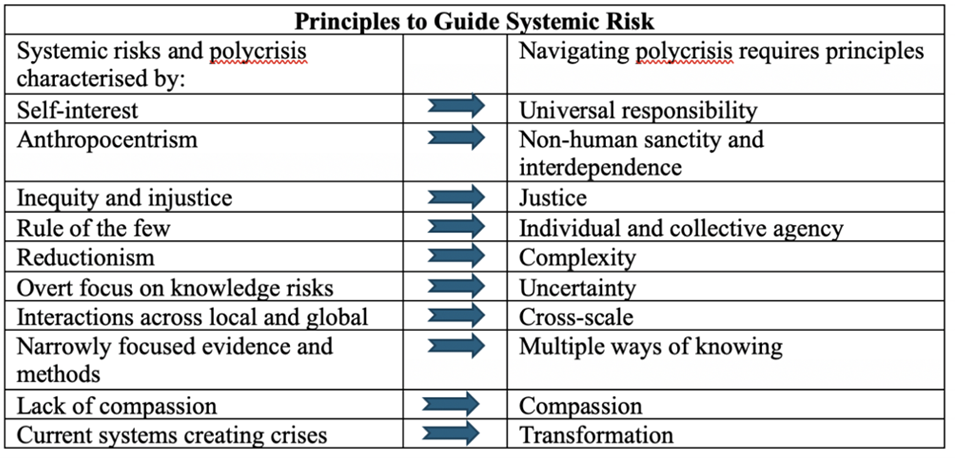

Navigating the polycrisis requires guiding principles. The principles of GCE provide a powerful way to guide our vision both as a diagnostic tool and as a way of finding common ground in diverse contentious settings. Such principles are found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Sustainable Development Goals (UN General Assembly, 2015), and the Dublin Declaration (GENE, 2022). These principles are equally important in systemic risk assessment and associated responses. For instance, the Accelerator for Systemic Risk Assessment (ASRA) has co-developed a set of principles for systemic risk assessment and responses to accelerate awareness of systemic risks and to guide collective, transformative action (Figure 1). Faced with multiple, interconnected, and compounding crises in global systems, ASRA is a new and unique initiative committed to radically rethinking risk as a way to improve decision-making about current and future challenges. Characteristics of systemic risks and polycrisis listed on the left (Figure 1) reflect the nature of our capitalist, neoliberal society. The list of principles (Figure 1) listed on the right has much in common with GCE.

Figure 1. Set of principles to guide systemic risk developed by ASRA (2024:12)

The fundamental challenge is that we have little if any precedents to guide us through these unchartered times. The pace of change is so rapid and uncertain that we are called upon to live in a new unprescribed manner. In the words of Bauman (2007) we are now living in ‘liquid times’ where thinking, planning and acting are no longer helping us in the way they did in the past.

The concept of hope

In light of this seemingly hopeless polycrisis, hope is a necessary part of our response. Successful social movements throughout history have stemmed from hopeful visions. For Skold, (2025: 2) ‘hope is the engine of all our actions, opening up a space in which something can happen’. In spite of the stark statistics, and gloomy predictions, Figueres and Rivett-Carnac (2020) argue that all is not lost as there is still time to choose our future and collectively create it. Their work highlights the power of human choice. According to Figueres and Rivett-Carnac:

“we still hold the pen. In fact, we hold it more firmly now than ever before. And we can choose to write a story of regeneration of both nature and the human spirit. But we have to choose” (Ibid.: 13).

Hope is situated within this space of human agency, and in the power of humans to successfully address this multifaceted challenge. While hope is deeply intertwined with different religions including Christianity and Islam, it also exists as a broader human emotion and concept with various interpretations and applications outside of religion. Hope and hopelessness are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, an acknowledgement of hopelessness can make room for hope. Lynch (1965) maintained that imagination freed people from hopelessness by presenting alternative realities to those currently being experienced.

The concept of hope has been explored by a number of influential educational theorists in philosophy, theology and psychology. For many philosophers, hope is a transformative force. Ernst Bloch, known as ‘the philosopher of hope’ (Hudson, 1979: 144) is known for the term ‘anticipatory consciousness’ which describes an individual’s ability to understand what has not been known. While Friedrich Nietzsche (1996) was cognisant of hope’s ability to nurture illusions, he did recognise the transformative power of hope. Hannah Arendt linked hope with freedom, by promoting action which generates transformative processes (Arnett, 2012). Lynch (1965: 23) defines hope as ‘an arduous search for a future good of some kind that is realistically possible but not yet visible’. Lynch highlighted two key aspects of hope, its relationship to realistic imagination and its collaborative nature. Henry Giroux’s (2018) concept of ‘educated hope’ refers to a form of hope cultivated through critical education, enabling individuals to critically analyse social structures and imagine alternative possibilities for a more just and democratic society. Dewey (2008: 294) distinguished hope from optimism, arguing that optimism ‘encourages a fatalistic contentment with things as they are’ while hope – or what the pragmatists called meliorism – is an active process, in which ‘by thought and earnest effort we may constantly make things better’. Aspirational hope should be differentiated from active/radical hope. Aspirational hope is about hoping for a sunny day or a lottery win. False hope can be a coping mechanism whereby people hope that things will improve on their own accord. Similarly wishful thinking is akin to believing that climate change is not serious or that someone else will fix the problem.

Active hope is more pragmatic and purposeful (Solnit and Young-Lutunatabua, 2023). Also described as ‘realistic hope’ (Hickey, 1986) or ‘constructive hope’ (Ojala, 2012), active hope includes considerations that one has the ability to overcome obstacles leading to constructive problem solving. Constructive hope refers to a form of hope fostering long-term, proactive environmental engagement at the collective (e.g. political engagement, participation in social movements, organisational change) and individual (e.g. lifestyle choices, individual actions) level (Vandaele and Stålhammar, 2022). Hope is more empowering than despair. It energises us, driving our desire to engage and to make a difference. Rebecca Solnit articulates this powerfully as follows:

“Hope… is an axe you break down doors with in an emergency. Hope should shove you out the door, because it will take everything you have to steer the future away from endless war, from the annihilation of the earth’s treasures and the grinding down of the poor and marginal. To hope is to give yourself to the future, and that commitment to the future makes the present inhabitable” (Solnit, 2016: 4).

Ojala (2012) talks about constructive hope. By helping to regulate students’ anxiety in the face of climate change, hope promotes awareness raising, knowledge learning and action competence development (Ojala, 2012). Ojala (2015) found constructive hope was higher when teachers accepted their students’ negative emotions about social and environmental problems, while also maintaining a positive and solution-oriented outlook in the classroom.

‘Hope’ is a word closely associated with the work of Paulo Freire. Freire considered hope to be an ‘ontological need’ (2004: 2) because it’s essential for our existence and our capacity to act in the world. In these terms, hope is not a passive wish but a fundamental human need, an inherent part of being. Freire believed that societal troubles could not be addressed without first believing that one was capable of addressing them. Freire cautioned against passive hopefulness, arguing that true hope requires action and commitment. Simply wishing for something to happen is not enough; hope needs to be anchored in practice and become a historical reality. Freire believed that without hope, there is no struggle, no motivation to challenge injustice and work towards a better future. Hope fuels the desire for change and provides the impetus for action. Freire emphasised that hope is intertwined with critical consciousness, or conscientização, which involves critical reflection on our own reality and the world around us. Freire saw education as a process of not just instilling hope, but of evoking and guiding it. He believed that education should empower individuals to recognise their own capacity for hope and to use it as a force for transformation (Webb, 2010). Freire’s educational philosophy offers a hopeful vision for what education can be: a tool for liberation, critical consciousness and social justice. For Giroux (2010: 719) who knew Freire for over 15 years, ‘hope for Freire was a practice of witnessing, an act of moral imagination that enabled progressive educators and others to think otherwise in order to act otherwise’. Moreover, ‘at a time when education has become one of the official sites of conformity, disempowerment, and uncompromising modes of punishment’ (Ibid.), the legacy of Paulo Freire’s work is more important than ever before.

Macy and Johnstone (2022: 4) refer to active hope as a practice, ‘something we do rather than something we have’. This practice according to the authors involves three steps: firstly, acknowledging how we feel, secondly, articulating what we would like to achieve and thirdly, identifying actions needed to achieve our goals. This approach is based on activating our sense of purpose through strengthening our capacity and commitment to act. Educationalists are faced with enormous challenges. During times of crises, how do teachers remain hopeful? Hope as an individual endeavour is not enough. It needs to inform educational policies and practices (Bourn, 2021). However, it is important to note that a declaration of hope can be a state of denial. According to Ojala (2015), this occurs among students when hope is interpreted as denial of the seriousness of climate change, so there is no need for concern. In such a scenario false hope or wishful thinking replaces agency and reduces a sense of responsibility for any environmental action.

Despair is natural when there’s objective evidence of a shared existential problem we’re not addressing adequately. Redirecting our anger and anxiety into constructive action, can alleviate stressful emotions. Indeed, a Finnish study of the relationship between hope and climate anxiety found that these emotions are not mutually exclusive but rather can operate simultaneously and even enhance each other in motivating action (Sangervo et al., 2022). In the words of Figueres and Rivett-Carnac (2020: 54) ‘we all have to be optimistic, not because success is guaranteed but because failure is unthinkable’. In other words, we simply cannot afford the luxury of feeling powerless. The irony is, in the absence of hope, there is a tendency to freeze up and surrender, while the opposite response to the climate emergency is absolutely essential. Developing the climate resilience of young people ‘involves experiencing both climate hope and distress and harnessing these cognitive and emotional responses for action’ (Finnegan, 2023: 1633). Educators play an essential role in supporting young people as they develop this resilience and maintain constructive hope.

Hope and GCE

GCE has been criticised for neglecting its radical roots (O’Toole, 2024; Bryan, 2011) while others have called for a more transformative approach (Dolan, 2024). Tarozzi (2023: 2) urges us to consider how we can ensure education is permeated with hope in order to ‘think otherwise and to lay the foundations for a new transformative pedagogy’. Such a pedagogy needs to devote more attention to the question of possible futures. Adopting futures thinking as a core educational imperative will equip learners with critical insight, creative power and hopeful agency in navigating and shaping our uncertain world (Hicks, 2014).

Hope plays a crucial role in GCE by fostering a sense of possibility and agency in addressing global challenges. GCE has the capacity to support learners in recognising the polycrisis in its totality and through its constituent parts can support them in navigating these uncertain times. The global context in which GCE occurs has shifted immeasurably. Hence, the first recommendation for GCE is to acknowledge the polycrisis and all of its complexities. It is imperative for GCE practitioners to facilitate learners in understanding the underlying mechanisms of the polycrisis. There is much we can do to defuse the polycrisis and this has to be the agenda for a hopeful pedagogy within and beyond GCE. Focusing on solutions rather than problems is psychologically advantageous. Indeed, authors such as Morin and Kern (1999) highlight the importance of complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity in the world as potential sources of creativity and transformation. Secondly, we must devote more attention to the study of possible futures and adopt transdisciplinary approaches to do so (Albert, 2024). The interdependent nature of the polycrisis demands a holistic, integrated approach. Addressing issues in isolation is insufficient. For instance, GCE sometimes operates apart from education for sustainability due to separate funding schemes, historical evolution and organisational bias. Thirdly, it is incumbent on all educators in general and GCE educators in particular to explore scenarios for the future which are hopeful, evidence based and achievable. Fourthly, GCE needs to facilitate hopeful action, including peaceful protests, in every space such as classrooms, organisations, communities and Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) clubs. By remaining silent and not speaking out against injustice, we implicitly support and enable the oppressive systems and actions that perpetuate inequality.

Conclusion

There will be a future. Of that we can be certain. The nature of this future remains to be seen. However, we are facing a predicament, a multiplicity of intersecting crises which need to be addressed ‘consciously, systematically and synthetically, taking account of all the most relevant parameters’ (Albert, 2024: 225). A broad spectrum of possible futures is plausible, ranging from a collapse of human civilisation to an extensive transformation of the economy and society and a reshaping of human-nature relationships. The polycrisis does not guarantee a global collapse, nor does it inspire a fairy tale ending. For Albert (2024) future outcomes will be determined by political agency, institutional choices, social movements and technological pathways. The genocide in Gaza highlights a failure of GCE to engage with the complexities of the conflict in a meaningful and critical way, leading to silences, inaction, and a perpetuation of existing power imbalances. A more critical, hopeful and socially just approach is needed to ensure that GCE can effectively contribute to a more equitable and peaceful world.

According to much of the literature discussed in this article, hope drives action, creativity and the collective construction of a sustainable future. It inspires us to collectively work together towards a shared vision of a better future. Hopefulness is best achieved through interpersonal connections such as community-based initiatives, collaborative partnerships and collective endeavours. According to Lynch (1965: 24) hope must in some way or another ‘be an act of community whether the community be a church or a nation or just two people struggling together to produce liberation in each other’. At its core, futures thinking is an act of hope. Apocalyptic scenarios and prophecies tend to disempower and alienate people. The very idea that there is a future is optimistic. For GCE, hope can be utilised as a dynamic force that transforms despair into energy for action. By questioning the root causes of the polycrisis, through critical dialogue, a series of alternative futures can be envisioned and through hopeful engagement, learners can be inspired to realise their own individual and collective agency. Paulo Freire’s pedagogy of hope applied to the polycrisis, offers a powerful framework for understanding and confronting the multiple and intersecting crises of our time. Through critical dialogue, solidarity and a commitment to collective action, Freire would argue that we can transform despair into action, reclaim our futures and co-create a more equitable, peaceful and sustainable world.

References

Accelerator for Systemic Risk Assessment (ASRA) (2024) ‘Facing Global Risks with Honest Hope: Transforming Multidimensional Challenges into Multidimensional Possibilities’, available: https://risk-assessment.files.svdcdn.com/production/assets/images/ASRA_Facing-Global-Risks-report_2024.pdf?dm=1726515340 (accessed 11 August 2025).

Albert, M J (2024) Navigating the Polycrisis: Mapping the futures of capitalism and the Earth, Massachusetts, MIT Press.

Amnesty International (2024) ‘You Feel Like You Are Subhuman: Israel’s genocide against Palestinians in Gaza’, 5 December, available: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde15/8668/2024/en/ (accessed 26 August 2025).

Arnett, R C (2012) Communication Ethics in Dark Times: Hannah Arendt's Rhetoric of Warning and Hope, Southern Illinois: SIU Press.

Bauman, Z (2007) Liquid Times: Living in an Age of Uncertainty Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bourn, D (2021) ‘Pedagogy of Hope: Global Learning and the Future of Education’, International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 65-78.

Bryan, A (2011) ‘Another cog in the anti-politics machine? The “de-clawing” of development education’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 12, pp. 1-14.

Chancel, L, Piketty, T, Saez, E, and Zucman, G (2022) World Inequality Report 2022, Paris: World Inequality Lab.

Dewey, J (2008) The Middle Works 1912–1914: [Essays, Book Reviews, Encyclopaedia Articles in the 1912–1914 Period, and Interest and Effort in Education], Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Dolan, A M (ed.) (2024) Teaching the Sustainable Development Goals to Young Citizens (10-16 Years): A Focus on Teaching Hope, Respect, Empathy and Advocacy in Schools, London: Taylor & Francis.

Figueres, C and Rivett-Carnac, T (2020) The Future we Choose: The Stubborn Optimist's Guide to the Climate Crisis. London: Manilla Press.

Finnegan, W (2023) ‘Educating for hope and action competence: a study of secondary school students and teachers in England’. Environmental Education Research, Vol. 29, No. 11, pp. 1617-1636.

Freire, P (2004) [1992] Pedagogy of Hope, London: Continuum.

GENE (Global Education Network Europe) (2022) The European Declaration on Global Education to 2050: The Dublin Declaration, Dublin: GENE.

Giroux, H A (2010) ‘Rethinking education as the practice of freedom: Paulo Freire and the promise of critical pedagogy’, Policy Futures in Education, Vol. 8, No. 6, pp. 715-721.

Hickey, S S (1986) ‘Enabling hope’, Cancer Nursing, Vol. 9, pp. 133–137.

Hicks, D (2014) Educating for Hope in Troubled Times: Climate Change and the Transition to a Post-Carbon Future, London: Institute of Education Press.

hooks, b (2003) Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope, New York: Routledge.

Hudson, W (1979) The Marxist Philosophy of Ernst Bloch, New York: Springer.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2022) ‘Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’, available: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGII_SummaryVolume.pdf (accessed 8 July 2025).

Kitzes, J, Wackernagel, M, Loh, J, Peller, A, Goldfinger, S, Cheng, D and Tea, K (2008) ‘Shrink and share: humanity's present and future Ecological Footprint’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, Vol. 363, No. 1491, pp. 467-475.

Lynch, W (1965) Images of Hope: Imagination as Healer of the Hopeless, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Macy, J and Johnstone, C (2022) Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in without Going Crazy, Novato, California: New World Library.

Morin, E and Kern, A B (1999) Homeland Earth: A Manifesto for the New Millennium, New York, Hampton Press.

Nietzsche, F (1996) [1878] Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Norton, A and Greenfield, O (2023) ‘Eco-Social Contracts for the Polycrisis’, available: https://www.greeneconomycoalition.org/assets/reports/GEC-Reports/GEC_Eco-Social-Contracts-Polycrisis-FINAL-Nov23.pdf (accessed 8 July 2025).

Ojala, M (2012) ‘Hope and Climate Change: The Importance of Hope for Environmental Engagement Among Young People’, Environmental Education Research, Vol. 18, pp. 625–642.

Ojala, M (2015) ‘Hope in the Face of Climate Change: Associations with Environmental Engagement and Student Perceptions of Teachers’ Emotion Communication Style and Future Orientation’, The Journal of Environmental Education, Vol. 46, No. 3, pp. 133–148.

O’Toole, B (2024) ‘The Silences of Global Citizenship Education: A Concept Fit for Purpose?’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 39, Autumn, pp. 171-183.

Roubini, N (2022) Megathreats, New York: Little, Brown.

Sangervo, J, Jylhä, K M and Pihkala, P (2022) ‘Climate anxiety: Conceptual considerations, and connections with climate hope and action’, Global Environmental Change, Vol. 76, p. 102569.

Selden, K and Selden, M (1990) The Atomic Bomb: Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Japan in the Modern World), Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

Sköld, A (2025) ‘Hope in the time of hopelessness’, Nordic Psychology, pp. 1-14.

Solnit, R (2016) Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities, Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Solnit, R and Young-Lutunatabua, T (eds.) (2023) Not Too Late: Changing the Climate Story from Despair to Possibility, Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Taneja, A, Kamande, A, Guharay Gomez, C, Abed, D, Lawson, M and Mukhia, N (2025) Takers Not Makers: The unjust poverty and unearned wealth of colonialism, Oxford: Oxfam, available: https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/621668/bp-takers-not-makers-200125-summ-en.pdf;jsessionid=83087DC7258A690A85907C54BB06EA54?sequence=1 (accessed 8 July 2025).

Tarozzi, M (2023) ‘Introducing Pedagogy of Hope for Global Social Justice’, in D Bourn and M Tarozzi (eds.) Pedagogy of Hope for Global Social Justice: Sustainable Futures for People and the Planet, London: Bloomsbury.

United Nations (1948) Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. 78 UNTS 277. Adopted 9 December 1948, entered into force 12 January 1951, available: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/1948/12/19481209%2000-17%20AM/Ch_IV... (accessed 25 August 2025).

UN General Assembly (2015) ‘Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’, Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015, available: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed 15 July 2025).

Vandaele, M and Stålhammar, S (2022) ‘“Hope dies, action begins?” The role of hope for proactive sustainability engagement among university students’, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, Vol. 23, No. 8, pp. 272-289.

Webb, D (2010) ‘Paulo Freire and “the need for a kind of education in hope”’, Cambridge Journal of Education, Vol. 40, No. 4, pp. 327-339.

Wilkinson, R and Pickett, K (2009) The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better, London: Allen Lane.

WWF (2024) Living Planet Report 2024: A System in Peril, Gland, Switzerland: WWF, available: https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/2024-living-planet-report (accessed 8 July 2025).

Anne M. Dolan is an associate professor and lecturer in primary geography with the Department of Learning, Society and Religious Education in Mary Immaculate College, Ireland. She is the author/editor of Teaching the Sustainable Development Goals to Young Citizens: A focus on hope, respect, empathy and advocacy’ (Routledge, 2024), Teaching Climate Change in Primary Schools: An Interdisciplinary Approach (Routledge, 2022), Powerful Primary Geography: A Toolkit for 21st Century Learning (Routledge, 2020) and You, Me and Diversity: Picturebooks for Teaching Development and Intercultural Education (Trentham Books/IOE Press, 2014). She is the co-ordinator of the M.Ed. in Education for Sustainability and Global Citizenship in Mary Immaculate College.