Espousing Hope or Entrenching Gloom? A Critical Discourse Analysis of Oxfam’s Global Inequality Reports Through the Lens of Freire’s Pedagogy of Hope

Development Education and Hope

Abstract: As inequality, climate crisis, and threats to democracy grow, debates on poverty and justice have become urgent. This article applies critical discourse analysis (CDA) and Paulo Freire’s ‘pedagogy of hope’ to examine how Oxfam’s global inequality reports (2016–2025) have evolved. It asks whether these reports only dramatise crisis or also foster hope and action. A comparison of ten reports shows a shift: earlier texts stressed crisis and elite blame, while later ones highlight collective action and alternatives. Using CDA’s three levels, text, discourse, and social practice, the study finds Oxfam increasingly challenges the view that neoliberalism is inevitable. Later reports emphasise feminist economics, grassroots organising, and fairer wealth distribution as real solutions. Guided by Freire’s idea that hope arises through struggle, the study shows that while early reports risked hopelessness, later ones invite readers to see themselves as agents of change. The article argues that advocacy texts can be pedagogical tools, naming injustice while building the emotional and political conditions for democratic renewal and resistance.

Key words: Critical Discourse Analysis; Pedagogy of Hope; Global Inequality; Development Education; Neoliberalism.

Introduction

Amidst today’s overlapping crises of climate change, growing inequality, democratic decline, and social division, discussions about poverty, wealth, and justice have become more urgent (Piketty, 2020; Stiglitz, 2019; IPCC, 2023). As wealth keeps concentrating in the hands of a few, and the unfair treatment of women and racial groups becomes clearer, more reports and campaigns have appeared to challenge inequality (Oxfam, 2020; UN Women, 2020; World Bank, 2023). One of the most important examples is Oxfam’s global inequality reports (2016–2025), which are widely quoted and emotionally powerful in development debates.

Each year, Oxfam releases its inequality reports to coincide with the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. Since An Economy for the 1% (Oxfam, 2016), they have combined World Bank and Credit Suisse data with stories from care workers, climate activists, and grassroots organisers. They frame inequality as the result of political choices and decades of neoliberal policy, not a natural outcome. Their power lies in mixing analysis with personal stories, showing inequality as both an economic and moral-political injustice. These reports matter as evidence-based studies and persuasive tools for change.

However, the reports raise important questions: do they only dramatise inequality and stir anger, or do they also build the hope and momentum for change? Giroux (2011) warns that while crisis language is vital, it can also overwhelm and disempower. Can Oxfam’s reports avoid hopelessness and instead build the ‘critical hope’ people need to imagine and pursue alternatives? This article addresses these questions through Freire’s ‘pedagogy of hope’ and Fairclough’s critical discourse analysis (CDA). Freire (1994) defines hope not as blind optimism but as a political commitment to struggle and change. Fairclough’s CDA examines how language frames issues, assigns roles, and uses moral and emotional appeals (Fairclough, 1992; 2013). Combining these, the article compares ten Oxfam reports (2016–2025) to show how they depict inequality, agency, and shifts between crisis, emotion, and hope. It argues that early reports focused on outrage and critique, while later ones stressed hope in action through grassroots change and collective effort.

Across the ten reports, three distinct stages can be identified. The first stage (2016–2018) is marked by strong crisis language and a discourse of outrage. The second stage (2019–2021) represents a transitional phase: while crisis narratives remain, the reports begin to highlight what can be done to change the situation, introducing proposals around care work, public services, and progressive taxation. The third stage (2022–2025) shows a clearer shift, with inequality described as ‘economic violence’ and greater focus placed on structural alternatives such as wealth redistribution, grassroots mobilisation, and challenges to corporate and monopoly power.

This study contributes to debates on development education and advocacy by highlighting stories that connect emotionally while empowering politically. It shows that effective language can both describe problems and inspire fairer futures. The article proceeds as follows: section one outlines the theory, combining Freire’s pedagogy of hope with Fairclough’s CDA. Section two covers the method; report selection, coding, and Fairclough’s three-part model. Section three presents findings on Oxfam’s shift from crisis talk to agency, moral appeals, and structural critique, and why these matter in practice. The conclusion reflects on the responsibility of communicators to use language that builds critical hope in times of crisis.

Theoretical framework

This study uses Paulo Freire’s pedagogy of hope and Norman Fairclough’s CDA, set within the broader field of development education and critical pedagogy. Together, these approaches help us see how Oxfam’s inequality reports use language to shape how people understand reality, view their ability to act, and imagine change. Freire’s Pedagogy of Hope (1994) builds on Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970), shifting from dialogue in learning to the emotional and political role of hope in creating change. For Freire, hope is not private optimism but a collective, historically grounded practice rooted in the fight for justice. As he explains, ‘without at least some hope, we cannot even begin the struggle. But without struggle, hope… becomes hopelessness’ (Freire, 1994: 3). This view has shaped development educators resisting the despair and depoliticisation of neoliberalism (Andreotti, 2011; Bourn and Tarozzi, 2023). Freire links hope to praxis, the cycle of reflection and action to change unjust systems (Freire, 1970). This aligns with development education’s goal to build not only awareness but also critical thinking and agency (Bourn, 2016). Tackling global inequality thus requires challenging narratives that naturalise poverty and instead promote visions of possibility and shared responsibility.

Fairclough’s CDA offers a way to study how language both shapes and is shaped by power (Fairclough, 1992; 2013). CDA sees discourse as a social practice and a site where ideas compete, reinforcing or challenging dominant norms. His three-part model; text, discursive practice, and social practice, helps analyse how Oxfam’s reports present inequality, agency, and moral appeals. This matters in development debates, often criticised for reproducing power imbalances (Escobar, 1995; Cornwall, 2007). Cornwall (2007) notes that buzzwords like ‘empowerment’ or ‘inclusive growth’ often mask structural causes of inequality. Even well-meaning debates can depoliticise injustice by stressing technical fixes over systemic change (Ferguson, 2017; Green, 2022; Kapoor, 2020). In global crises, communication must move beyond problem description. Freire stresses the need to raise critical awareness and build collective action (Bourn and Tarozzi, 2023). Together, CDA and Freire’s pedagogy of hope ask: do these texts provide the emotional, ethical, and political basis for real change?

This framework situates Oxfam’s inequality reports (2016–2025) within wider debates on language, power, and hope. Using Fairclough’s CDA, the study examines how the reports present inequality through data, moral appeals, and personal stories. Through Freire’s lens, it asks: do these narratives spark outrage without stifling imagination? Do they model a pedagogy of hope that supports action and collective struggle, or risk becoming a pedagogy of gloom that breeds despair?

Methodology

This study applies Fairclough’s (1992, 2013) three-part CDA model to analyse how Oxfam’s inequality reports (2016–2025) shifted in language and focus. Over a decade marked by rising inequality, COVID-19, ecological crises, and populism, the reports grew more critical of neoliberal capitalism and extreme wealth. The analysis tracks how Oxfam’s narratives of injustice and possibility evolved in response to global events. Freire’s Pedagogy of Hope (1994) is used to assess whether the reports inspire collective action or reinforce despair. Following Freire’s history-based critique, the study situates Oxfam’s changing discourse within broader shifts in economic restructuring, climate crisis, and debates on civil society’s role in governance.

Corpus and inclusion criteria

The study is based on ten Oxfam global inequality reports published between 2016 and 2025. Together, these reports provide a useful way to track changes in language over a decade shaped by multiple global crises. The selection was clear: only the main inequality reports released during the World Economic Forum in Davos were used, since these are Oxfam’s most visible contributions to global debates on inequality. Shorter briefings or topic-specific papers were left out to keep the sample consistent and comparable.

Analytical framework

The analysis draws on Fairclough’s three-part CDA framework:

- Textual analysis: The analysis coded individual words, phrases, metaphors, evaluative language, and narrative structures. Examples include words describing inequality (‘dangerous’, ‘unprecedented’, ‘explosive’), common phrases like ‘an economy for the 1%’, and emotions such as fear, anger, and hope. The study also looked at how inequality, power, and agency were presented, and how moral and emotional appeals were built.

- Discursive practice: The study also examined how the reports are produced, shared, and used in the development field, looking at their timing during the World Economic Forum in Davos and their dual role as advocacy tools and teaching resources. It also looked at how the reports addressed different audiences (policymakers, media, civil society) and how they positioned themselves in relation to global elites. For example, showing billionaire wealth figures alongside the personal stories of women workers was coded as a ‘contrapuntal framing’ strategy.

- Social practice: The reports’ language was interpreted in relation to wider political and ideological contexts like neoliberalism, global governance, and grassroots resistance. This included situating reports within austerity debates (2016–2019), the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022), and the corporate power turn (2024 onwards).

To bring in Freire’s pedagogy of hope, the study asks whether the reports use what Bourn and Tarozzi (2023) call a discourse of critical hope. This meant checking if the reports (a) describe systemic injustice in ways that make people think critically, (b) present clear visions for change based on solidarity, and (c) build emotional awareness that supports civic action and resistance.

Coding Process

The coding framework was developed iteratively: open coding identified recurring phrases, rhetorical devices, and emotions, which were then grouped into themes such as crisis framing, moral outrage, policy solutions, and hope-focused narratives. Each theme was defined in a codebook with inclusion/exclusion rules—for example, ‘hope-oriented narratives’ required explicit references to transformation or collective agency but excluded vague optimism without action. Changes over time were tracked by noting how often themes appeared and how they were used in context. Early reports were dominated by crisis language; from Time to Care (Oxfam, 2020) onward, hopeful framings strengthened, focusing on feminist and care-based solutions.

Comparative and Longitudinal Analysis

Because the reports cover a long period, a comparative approach was used to track how Oxfam’s language and strategies changed over time. This involved identifying:

- Discursive shifts: how the way inequality, agency, and hope were framed changed in response to global events like the pandemic or the rise of economic populism.

- Discursive consistencies: repeated patterns such as metaphors (‘an economy for the 1%’), familiar value-based messages, and stable ways of framing issues.

- Authentic struggle: how the reports show grassroots resistance and movement-building in ways that connect with Freire’s idea of praxis.

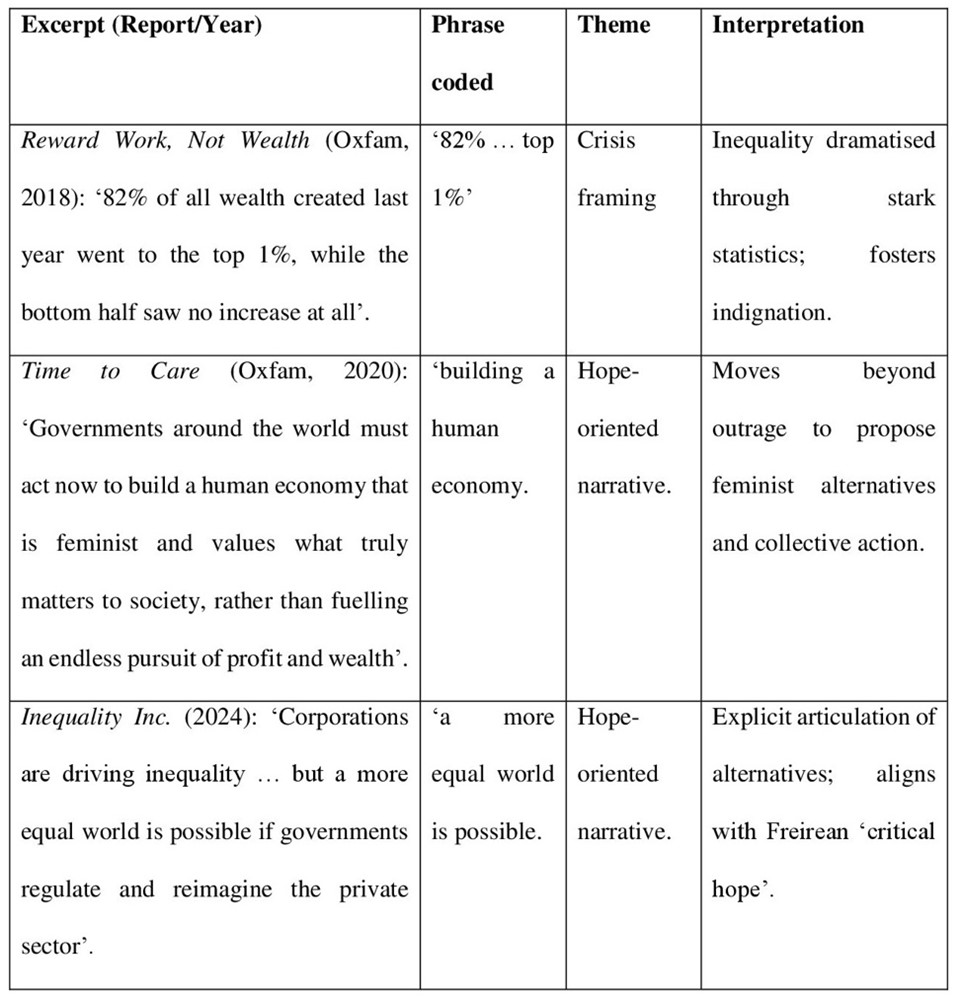

Illustrative Coding Table

An illustrative extract is shown in the table below, demonstrating how specific excerpts were coded into themes and linked to interpretive insights. For example:

By combining theme-based coding with long-term comparison, this approach provided both depth and reliability. Using a codebook, clear selection rules, and examples makes the study more transparent and offers a framework that others can adapt in development education and discourse analysis.

Validity and reflexivity

Because discourse analysis is interpretive, coding was flexible and repeated, cross-checking report sections, summaries, recommendations, personal stories, and related literature (Cornwall, 2007; Escobar, 1995). The study focuses only on the texts themselves, not on how audiences received them or how they were produced. This limitation points to future research, such as interviews, audience studies, or institutional ethnography. Researcher perspective shaped coding choices, but making the process transparent strengthens credibility. Ultimately, the study aims not only to analyse Oxfam’s language but to assess how it reflects Freire’s vision of discourse as a tool for change, building solidarity, emotional strength, and imagination in the face of injustice.

Findings

The CDA of Oxfam’s inequality reports (2016–2025) shows a mix of crisis stories, moral appeals, and rhetorical strategies that move between despair and hope. Over the decade, the reports focus on the structural causes of inequality while also trying to keep readers engaged as agents of change and encourage collective action.

Crisis and gloom: naming catastrophe

A key feature of Oxfam’s inequality reports is their strong crisis language to show the scale and structure of global inequality. An Economy for the 1% (Oxfam, 2016) used striking statistics, ‘In 2015, just 62 individuals had the same wealth as 3.6 billion people’ (Oxfam, 2016: 1) to spark outrage and present inequality as structural violence rather than a natural outcome of growth. Later reports intensified this. The 2017 and 2018 editions used terms such as ‘billionaire bonanza’ (2018: 19), ‘inequality crises’ (2017: 5), and ‘crony capitalism’ (2017: 4) to highlight deliberate injustice. By 2020-2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, inequality was labelled ‘deadly’, ‘exploitative’, and a ‘compounding risk’ (Oxfam, 2021). The 2023 and 2024 reports went further, framing a ‘polycrisis’ caused by pandemic aftershocks, climate breakdown, and corporate profiteering.

This discourse operates at the textual level of Fairclough’s (1992) CDA, where vocabulary, metaphor, and narrative structure carry ideological weight. As Cornwall (2007) and Escobar (1995) note, development discourse shapes both problems and responses. Oxfam’s crisis framing exposes inequality as constructed but also echoes Swilling’s (2019) ‘catastrophe narrative’, which generates urgency yet risks fatalism without solutions. This is the core tension. Freire (1994) stresses that naming oppression is necessary but insufficient. Language steeped in despair can foster what Giroux (2011: 73) calls ‘corrosive cynicism’, the belief that injustice is permanent and resistance futile. While the reports denaturalise neoliberal inequality, early editions often cast people only as victims. Their strong denunciations had emotional impact but left readers stalled in critique without clear pathways for action.

The reports challenge dominant stories that justify inequality through meritocracy or effort. They embody what Fairclough (2013) calls a critical semiotics of resistance, reframing economic crisis as moral and political injustice. The 2016-2018 reports depict inequality as a global emergency, using contrasts, exaggeration, and moral condemnation. This made inequality visible and urgent but risked leaving readers passive. Later reports introduced hopeful alternatives, yet crisis language still dominated. The next section shows how hope was layered onto this despair, making the discourse more complex.

Hope and agency: constructing possibility

From 2019 onward, Oxfam’s language shifted from crisis to emphasising agency, alternatives, and political imagination. Instead of only describing a broken system, the reports argued that ‘another world is possible’, stressing that inequality is ‘the result of political and economic choices’ (Oxfam, 2022: 24). Time to Care (Oxfam, 2020) showed how unpaid care work, especially by women, drives inequality and proposed solutions: more public investment, fairer sharing of work, and valuing care. This marked a move toward what Freire (1994) calls a pedagogy of hope, sustaining anger at injustice without sliding into despair. Later reports reinforced this framing. The Inequality Virus (Oxfam, 2021: 16) argued COVID-19 reshaped what is possible, citing expanded healthcare and fairer tax reforms. Survival of the Richest (Oxfam, 2023) and Inequality Inc. (Oxfam, 2024) highlighted grassroots resistance, community ownership, and wealth redistribution as real alternatives. This reflects Giroux’s (2011: 108) ‘educated hope,’ where critique is tied to practical, action-oriented change.

From a CDA perspective, this marks an important shift. Fairclough (1992) argues that texts shape ideological struggles by defining roles. Earlier reports cast readers as observers, while later ones present them as agents of change. Phrases like ‘clawback democracy’ (Oxfam, 2024: 32), ‘collectively bargain’ (Oxfam, 2022: 46), and ‘fund just transitions’ (Oxfam, 2023: 14) show a move from moral appeals to calls for action. This aligns with debates in development education, where Bourn and Tarozzi (2023) and Andreotti (2011) urge moving beyond critique to building capacity for change and resilience. Oxfam’s later reports reflect this by pairing moral language with real cases, from Argentinian co-operatives and Indian farmer movements to feminist budgeting and global tax justice campaigns. These examples go beyond proposals, demonstrating resistance and new ways of imagining change.

The reports show that emotional engagement is central to political understanding and collective action. After 2019, Oxfam’s message shifts from diagnosing problems to action, from fatalism to future possibilities. They reflect critical pedagogy’s goals: exposing power and building people’s capacity to act. This change is both stylistic and ideological, rejecting the normalisation of inequality and amplifying the voices and strategies of those driving systemic change.

Comparative discursive features

Oxfam’s 2016–2025 reports shift from focusing on catastrophe to highlighting possibilities for change, reshaping both how inequality is framed and how readers see themselves. This reflects changes in Oxfam’s language and wider debates in development communication. The early reports (2016–2018) describe inequality as ‘a rigged system’ (Oxfam, 2018: 27), ‘unjust’ (Oxfam, 2016: 18), and a ‘major threat’ (Oxfam, 2017: 2). While morally powerful, this framing presents inequality as structural, external, and overwhelming. These narratives offered little guidance on dismantling or reimagining systems. As Fairclough (1992) warns, critical discourse can reinforce the very power structures it critiques if it lacks real alternative narratives.

Although Reward Work, Not Wealth (Oxfam, 2018) relies mainly on crisis language, it quietly introduces alternative terms. Phrases like ‘a human economy’ (Oxfam, 2018: 13) and references to collective bargaining and democratic business models show early experiments with ideas beyond neoliberalism. These were overshadowed by strong moral framing but foreshadowed the more action-focused language of later reports. The 2019-2021 reports mark a transition: crisis language remained but was increasingly paired with policy proposals and accountability demands. Time to Care (Oxfam, 2020) highlighted care work as central to feminist and economic justice, while The Inequality Virus (Oxfam, 2021) pointed to wealth taxes and universal healthcare as responses to pandemic-driven inequality.

In the later reports (2022–2025), the language becomes more confident and hopeful. Inequality is framed as ‘a political choice’ (Oxfam, 2022: 24), with solutions centred on reclaiming public wealth, democratic control, and community power. From 2022, Oxfam adopts a pedagogy of hope, stressing feminist economics, collective action, and movement-led change. This hopeful tone coexists with crisis language, reflecting tension between catastrophe and transformation. Inequality Kills (Oxfam, 2022) goes further, portraying inequality as not just immoral but deadly, a form of permitted harm. It calls for wealth redistribution, billionaire taxes, and ending monopoly power, breaking from narrow technocratic reforms. This reflects Meade’s (2023) idea of epistemic repair: reclaiming discourse from managerialism to expose inequality as policy-driven violence. Inequality Inc. (Oxfam, 2024) continues this Freirean approach, demanding movement-led change and reclaiming the commons. The 2025 report, Takers, Not Makers (Oxfam, 2025), marks the peak of this shift. Although stark, predicting five trillionaires amid mass poverty, it signals structural possibility rather than despair. By branding billionaires ‘takers,’ it challenges the legitimacy of elite wealth. The report calls for reparations, decolonising the economy, and democratising finance, rooted in grassroots power and historical justice. In Freire’s terms, this is not only denunciation but also annunciation: a call to collective action grounded in critical hope.

Early reports portray the poor as passive victims, while later ones present them as organised political actors. This shift is educationally significant. As Bourn and Tarozzi (2021: 219) note, development education must go beyond awareness to building agency for action against injustice. The emotional tone also shifts: early texts stress outrage, while later ones highlight solidarity, pride, and hope. This mix of crisis and hope reflects global events and advocacy strategies. From a CDA perspective, it shows Oxfam’s effort to resist neoliberalism not only through critique but by imagining alternatives based on justice and care. In short, the reports move from describing injustice to imagining possibility, from despair to determination. This reflects Freire’s praxis: naming the world not just to describe it, but to change it.

Discursive practices: mobilising moral and emotional appeals

Beyond the text, Oxfam’s inequality reports act as interventions, designed to spark moral concern and emotional response. From Fairclough’s (1992) second level of CDA, discursive practice, they are more than research findings; they are deliberate messages to shape perception, stir emotion, and invite judgment. A key strategy is Oxfam’s strong moral language, describing inequality as ‘obscene’ (Oxfam, 2024: 5), ‘violent’ (Oxfam, 2022: 15), ‘deadly’ (Ibid.: 4), and ‘deliberate’ (Oxfam, 2016: 6). This framing turns inequality from a statistic into an ethical and political crisis, presenting economic disparity as a violation of shared values. It reflects van Dijk’s (1998: 63) notion of ‘norm violation’, pushing readers to see inequality as both illegitimate and urgent.

These moral messages are reinforced by emotional appeals that build solidarity. Time to Care (Oxfam, 2020) combines data on wealth hoarding with stories of women burdened by unpaid care, creating empathy and exposing systemic neglect. The Inequality Virus (Oxfam, 2021) deepens this by showing shared vulnerabilities during COVID-19, blending grief with connection. The reports also use storytelling, sharing testimonies from farmers, care workers, and activists, blending personal voices with structural critique. This reflects Fraser’s (2017) call for a politics of recognition and redistribution, where lived experience complements systemic analysis. It also echoes Freire’s vision of education as dialogue, amplifying rather than speaking for the oppressed.

A key part of Oxfam’s strategy is timing. Each report is launched during the World Economic Forum in Davos, the symbolic centre of the neoliberal order it critiques. This counter-positioning challenges the dominant story of ‘inclusive capitalism’ with one of exclusion and elite capture. As Fairclough (2013) notes, discourse derives power not only from content but also from timing and context. Over time, Oxfam’s language shifts from accusation to invitation. Early reports cast readers as witnesses, while later ones, like Inequality Inc. (Oxfam, 2024), call on civil society, unions, and educators to act. This reflects Andreotti’s (2011: 8) shift from ‘charity to solidarity’, moving from seeing the poor as victims to recognising all as agents of change within oppressive systems. This change in audience engagement aligns with Freire’s praxis. The reports aim not just to inform but to spark reflection and action, shaping conscience and collective will as liberating communication. Oxfam’s language is part of a wider network of international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) such as ActionAid and Christian Aid, which also frame issues around structural injustice, solidarity, and hope.

ActionAid’s Who Cares for the Future? (2020) highlights unpaid care as gender-based exploitation, echoing Oxfam’s critique of patriarchal economies. Christian Aid’s The Big Shift (2017) likewise calls for fossil fuel divestment and climate finance justice. These suggest more evidence of critical and systemic thinking in the INGO sector. However, Fricke (2022) found that this is not being translated into development education practice with most INGOs in Ireland ignoring neoliberalism as the main driver of poverty and inequality. Alldred (2022) argues that hope must be radical and structural, not just motivational. His focus on participatory learning and systemic critique mirrors Oxfam’s move from outrage to agency. Like Oxfam, Fricke (2022) links climate breakdown, colonial legacies, and economic injustice, urging learners to act on these connections. This reflects the growing overlap between activist communication and radical pedagogy, where hope is seen not as illusion but as praxis.

McCloskey (2019) critiques the technocratic framing of development and the limits of the Sustainable Development Goals, arguing that many INGOs operate within a managerial aid model that obscures structural injustice. He calls for transformative, politicised narratives. Oxfam’s later reports reflect this by framing inequality through extractive capitalism, women’s unpaid care, and racial injustice. In short, Oxfam’s reports are more than advocacy tools; they are emotional and moral texts that challenge dominant ideas, provide ethical clarity, and build political hope. They embody what Giroux (2011) calls public pedagogy: education beyond classrooms that shapes how people see the world and their role in it.

While this article has focused on the textual content of Oxfam’s reports, they are also received and used through specific channels. Released during the World Economic Forum in Davos, the reports gain wide media attention. For example, Oxfam’s 2016 headline that ‘the richest 1% own more wealth than the rest of the world’ (Oxfam, 2016) was reported by The Guardian (Elliott, 2016), BBC News (2016) and Al Jazeera (2016). The reports have influenced civil society debates, supported Oxfam’s Even It Up campaign (Oxfam, 2014), and shaped policy in national parliaments. For example, journalist Kelvin Chan notes that Portugal introduced a windfall tax on energy companies and major food retailers in 2023 after the release of Survival of the Richest (Oxfam, 2023) (Associated Press, 2023). In universities, they are valued in development studies for clarity, data, and moral framing. By combining personal stories with feminist and decolonial critique, they also serve as teaching tools in justice-focused classrooms. As advocacy texts, they act as public education, showing inequality as both economic fact and moral-political crisis demanding action. Their wide reach and strong language make them central to today’s development debates.

Social practices and neoliberal contexts

To understand the impact of Oxfam’s inequality reports, they must be placed within the wider social practices they reflect and challenge. Fairclough’s (1992) third level of CDA shows how texts link to broader structures of power, ideas, and material conditions, in this case, the global neoliberal order and its crisis. The reports emerged amid rising wealth concentration, weakened public services, climate breakdown, and political disillusionment, signs of what Brown (2015) calls neoliberalism’s stealth revolution, which reshapes society around market rules. As a dominant project, neoliberalism redefines citizenship and value, sidelining solidarity, the public good, and collective resistance.

The early Oxfam reports (2016–2018) frame inequality as a scandal of elite excess, exposing billionaire wealth and policy complicity. Though powerful, these critiques remain reformist, urging elites to act more responsibly. As Kapoor (2020: 49) notes, mainstream development debates often reflect ‘reformist’ neoliberalism, criticising excess without questioning the system itself. The 2019-2021 reports shift focus to public services, care work, and progressive taxation. Yet they still emphasise policy fixes, reflecting a technocratic optimism akin to Ferguson’s (2017) anti-politics machine, which treats structural crises as technical rather than political problems.

The later reports (2022–2025) show a clear break in language. Inequality is framed as systemic, intentional, and historically rooted. The focus shifts to structural change, breaking up concentrated wealth, and movement-led transformation. Survival of the Richest (Oxfam, 2023) and Inequality Inc. (Oxfam, 2024) criticise monopoly power and democratic decline, calling for reclaiming public wealth and political agency. This marks a move from appealing to elites toward aligning with global movements for justice, reparations, and sustainability. From a Freirean view, this is a shift from denunciation to annunciation, from naming oppression to affirming collective liberation (Freire, 1970; 1994). The later reports embody praxis, combining critique with actionable hope. They resist fatalism by highlighting resistance, centring oppressed voices, and proposing a new social contract instead of small reforms. This change is also pedagogical. Rather than treating readers as consumers or donors, Oxfam increasingly frames them as actors in a wider historical struggle. They echo Fraser’s (2017: 29) ‘triple movement’, resisting market fundamentalism and authoritarianism while building solidarity rooted in redistribution, recognition, and representation.

Seen this way, the reports act as public counter-narratives, challenging dominant ideas and fostering alternative visions. They reflect what Andreotti (2011) calls a postcolonial turn in development education, which views the global South not in deficit terms but as a source of knowledge and political power. The changes in Oxfam’s language also echo what Meade (2023) identifies as a core problem in development, the invisibility of neoliberalism. Drawing on Fricker’s concept of hermeneutical injustice, Meade warns that without clear critiques of neoliberalism, communities lack the tools to understand it and risk capture by far-right narratives. By naming inequality as a political choice and promoting collective action, Oxfam’s recent reports reclaim discourse as a tool for radical hope, epistemic repair, and transformative imagination in line with Freire’s vision.

At the social level, Oxfam’s reports shift from limited critique to a more liberating kind of discourse. They challenge neoliberal beliefs that inequality is unavoidable, charity is enough, or elites must lead change. In the later reports, they adopt a Freirean vision where naming the world goes hand in hand with transforming it, and critical hope becomes a shared practice of liberation. The mix of catastrophic language and hopeful alternatives shows the reports trying to balance between rejecting neoliberal fatalism and avoiding naïve optimism.

Implications for development education: pedagogy as praxis

These findings have key lessons for development education and advocacy. As Bourn (2016) notes, development education must go beyond awareness to build agency. Oxfam’s shift in language, from moral condemnation to grassroots resistance, mirrors this approach, offering a model for more active, transformative learning. The later reports combine structural critique with community-led solutions, reflecting Freire’s view that hope is inseparable from struggle.

While Oxfam’s inequality reports have strong potential as advocacy and public education tools, there remains a gap between their messages and regular use in development education. McCloskey (2019) warns that their transformative potential is often underused by both development education and international development sectors. This article therefore urges Oxfam and other INGOs to go beyond dissemination and integrate the reports into education programmes. Doing so would link advocacy with pedagogy, ensuring their emotionally powerful and structurally critical messages shape classrooms, teacher training, and student learning. Embedding the reports in curricula can build critical awareness, solidarity, and agency, turning advocacy into lived educational practice.

Finally, this study adds to research that views development discourse as a site of struggle, not only over facts but also over the very possibility of hope (Bourn and Tarozzi, 2023; Swilling, 2019). In today’s context of ecological crisis, authoritarianism, and rising inequality, naming injustice is insufficient without fostering collective action and solidarity. As Freire (1994) reminds us, hope is both emotional and political, it rejects fatalism. At their best, Oxfam’s inequality reports show how development discourse can serve as a tool for hope, linking anger to imagination, diagnosis to possibility, and critique to collective action.

Conclusion

This article examined Oxfam’s inequality reports (2016–2025) through Fairclough’s critical discourse analysis and Freire’s pedagogy of hope. The analysis shows a discourse moving between exposing systemic inequality and encouraging collective action. While the reports document the ‘rigged systems’ behind inequality, their crisis-heavy framing risks despair unless balanced with possibility. Over the decade, however, they shifted from moral outrage to grassroots mobilisation and systemic alternatives, reflecting Freire’s view of hope as central to social change. By releasing these reports to coincide with the World Economic Forum in Davos, Oxfam inserted a counter-narrative into a space dominated by neoliberal ideas of growth and prosperity. This underscores the educational and political stakes of framing inequality, it shapes not only how we see injustice but also our capacity to imagine and pursue alternatives.

For development educators, civil society actors, and policy practitioners, the challenge is not just to analyse these reports but to act on them. Oxfam’s reports are valuable tools for embedding critical awareness of inequality in teaching and civic education, helping students and communities question injustice while building agency. They also give civil society organisations a base for turning global analysis into local advocacy, on fair taxation, public services, or regulating monopoly power. At the same time, they promote alliances across feminist, climate, labour, and racial justice movements by linking issues such as unpaid care, extractive capitalism, and climate breakdown into a shared agenda. Most importantly, they show advocacy need not rely only on catastrophe: the reports can model what Freire called a pedagogy of hope, combining structural critique with stories of resistance and transformation.

In this way, the reports are more than advocacy tools; they are also educational resources. When used by practitioners and educators, they can build critical awareness, resilience, and collective imagination to confront inequality. Development education has a key role in ensuring these analyses become not just awareness-raising moments but catalysts for policy change and civic action. By linking anger with hope and words with action, Oxfam’s reports can inspire strategies for economic justice and democratic renewal.

References

ActionAid (2020) ‘Who cares for the future? Finance gender-responsive public services!’, available: https://actionaid.org/publications/2020/who-cares-future (accessed 20 June 2025).

Al Jazeera (2016) ‘Super-rich: 62 people own as much as half the world’, Al Jazeera, 18 January, available: https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2016/1/18/super-rich-62-people-own-as-... (accessed: 05 September 2025).

Alldred, N (2022) ‘Development Education and Neoliberalism: Challenges and Opportunities’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 34, Spring, pp. 112-123.

Andreotti, V (2011) Actionable Postcolonial Theory in Education, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Associated Press (2023) ‘Oxfam: Billionaires’ wealth surged during pandemic while poor faced inflation and hardship’, AP News, 16 January, available: https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-inflation-oxfam-international-... (accessed 22 August 2025).

BBC News (2016) ‘Oxfam says wealth of richest 1% equal to other 99%’, BBC, 18 January, available: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-35339475 (accessed: 05 September 2025).

Bourn, D (2016) Understanding Global Skills for 21st Century Professions, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bourn, D and Tarozzi, M (2023) Pedagogy of Hope for Global Social Justice: Sustainable Futures for People and the Planet, New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Brown, W (2015) Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution, New York: Zone Books.

Christian Aid (2017) The Big Shift Global Toolkit: Advocacy and Campaign Planning, London: Christian Aid.

Cornwall, A (2007) ‘Buzzwords and Fuzzwords: Deconstructing Development Discourse’, Development in Practice, Vol. 17, No. 4–5, pp. 471–484.

Elliott, L (2016) ‘Richest 62 people as wealthy as half of world's population, says Oxfam’, The Guardian, 18 January, available: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jan/18/richest-62-billionaires... (accessed: 05 September 2025).

Escobar, A (1995) Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Fairclough, N (1992) Discourse and Social Change, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Fairclough, N (2013) Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language, New York: Routledge.

Ferguson, J (2017) Give a Man a Fish: Reflections on the New Politics of Distribution, Durham: Duke University Press.

Fraser, N (2017) ‘Crisis of Care? On the Social-Reproductive Contradictions of Contemporary Capitalism’ in T Bhattacharya (ed.) Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression, pp. 21–36, London: Pluto Press.

Freire, P (1970) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York: Herder and Herder.

Freire, P (1994) Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed, London: Continuum.

Fricke, H-J (2022) ‘International Development and Development Education: Challenging the Dominant Economic Paradigm?’, Belfast and Dublin: Centre for Global Education and Financial Justice Ireland.

Giroux, H A (2011) On Critical Pedagogy, New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Green, D (2022) How Change Happens, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) (2023) ‘Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report’, Geneva: IPCC.

Kapoor, I (2020) Confronting Desire: Psychoanalysis and International Development, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

McCloskey, S (2019) ‘The Sustainable Development Goals, Neoliberalism and NGOs: It’s Time to Pursue a Transformative Path to Social Justice’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 29, Autumn, pp. 152–159.

Meade, E (2023) ‘Epistemic Injustice, the Far Right and the Hidden Ubiquity of Neoliberalism’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 38, Spring, pp. 14–33.

Oxfam (2014) ‘Even It Up: Time to End Extreme Inequality’, Oxford: Oxfam International, available: https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/even-it-up-time-to-end-extre... (accessed 6 August 2025).

Oxfam (2016) ‘An Economy for the 1%’, Oxford: Oxfam International.

Oxfam (2017) ‘An Economy for the 99%’, Oxford: Oxfam International.

Oxfam (2018) ‘Reward Work, Not Wealth’, Oxford: Oxfam International.

Oxfam (2019) ‘Public Good or Private Wealth?’, Oxford: Oxfam International.

Oxfam (2020) ‘Time to Care: Unpaid and Underpaid Care Work and the Global Inequality Crisis’, Oxford: Oxfam International.

Oxfam (2021) ‘The Inequality Virus: Bringing Together a World Torn Apart by Coronavirus Through a Fair, Just and Sustainable Economy’, Oxford: Oxfam International.

Oxfam (2022) ‘Inequality Kills: The Unparalleled Action Needed to Combat Unprecedented Inequality in the Wake of COVID-19’, Oxford: Oxfam International.

Oxfam (2023) ‘Survival of the Richest: How We Must Tax the Super-Rich Now to Fight Inequality’, Oxford: Oxfam International.

Oxfam (2024) ‘Inequality Inc: How Corporate Power Divides and Endangers the World’, Oxford: Oxfam International.

Oxfam (2025) ‘Takers not Makers: The Unjust Poverty and Unearned Wealth of Colonialism’, Oxford: Oxfam International.

Piketty, T (2020) Capital and Ideology, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Stiglitz, J (2019) People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent, New York: W.W. Norton.

Swilling, M (2019) The Age of Sustainability: Just Transitions in a Complex World, Abingdon: Routledge.

UN Women (2020) ‘From Insights to Action: Gender Equality in the Wake of COVID-19’, New York: UN Women, available: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/09/gender-e... (accessed 6 August 2025).

van Dijk, T A (1998) Ideology: A Multidisciplinary Approach, London: SAGE Publications.

World Bank (2023) ‘Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2023: Reversals of Fortune’, Washington, DC: World Bank.

Benedict Arko is a lecturer at the Department of Geography Education, University of Education, Winneba in Ghana. His research interests are in critical development discourse analysis, regional economic development, regional development planning, decentralised governance and mining, environment and livelihoods.