The Future of Film Training

Development Education and Film

Fiat Lux/Let light be made

Any approach to the future of film training must be framed by the dynamic of the changing technological and institutional circumstances of the moment. Considerations should also commence with a rigorous and fresh examination of the formation of the culture industry at present, analysing its determinations and effects, its mechanisms and methods.

Inevitably my perspectives were formed by the specific experience of carrying the unwieldy intellectual framework of 1970s French structural theory into the institutions of British television and Irish cinema. I was involved in commissioning for Channel 4 television in Britain during its most radical phase in the 1980s – working inside a television station for a decade one could observe the operations of the machinery of the media in close proximity. This was followed by a further ten years directing a national film agency, Bord Scannán na hÉireann/the Irish Film Board, which was focused on cinema although inevitably this involved television partnerships and, increasingly, transmedia connections through digital formats.

This article is also part of a longer term reflection on the developing institutions and structures of the film and television industries, their policies and practices, in various parts of the world. Moving images are part of a pervasive image system which crosses the globe, reiterating authorised narratives that disclose events deceptively. Training young people to enter that system involves the development of critical practitioners who have developed an emancipatory intelligence themselves (Petrie & Stoneman, 2014).

The French magazine Trafic (2004) was not overstating the crisis when suggesting that contemporary cinema ‘neither apprehends our reality honestly nor does it aid in imagining a different kind of future. It is suffocated by a set of anachronistic conventions dictated by the agents of commerce.’ The domination of the US model can be challenged and relativised by different forms of filmmaking from outside, but diverse cinemas from other countries and cultures are already situated as marginal and subordinate. Other cinemas are excluded by a dominant American cinema, commercial and confident, which contributes to the contemporary world’s image of itself and is embedded in a resilient ideology which interacts with the economic order.

There is a continuity in the assumed relations between the different parts of the world in both the academy and the wider public sphere. This is exemplified by the relatively recent introduction of terms like ‘World Art’ and ‘World Music’ for the study of history of art and musicology in the West. Any belated attempt to broaden the inclusivity of scholarly disciplines is to be welcomed, although there never was any reason why visual culture in Mexico or literary traditions in China or music in Mozambique should not have been an integral part of any substantial exploration of cultural genres. The Western academy imports frames of reference and angles of approach formulated within its own insular assumptions – which determine how we look at Western and therefore all other art forms.

For clear historical and political reasons it is not surprising that some of the most dynamic new filmmaking comes from the cultures of the global South – where the very act of making cinema is both more difficult and more urgent. Alongside helping to set up the Huston School of Film & Digital Media (part of the National University of Ireland, Galway) for the last ten years I have also been involved in peripatetic workshops in West Africa, and several EU funded training initiatives in the Maghreb and the Middle East (see Stoneman, 2012, 2013). These short-term schemes bring new filmmakers from the global South together for a short series of workshops to develop and strengthen their potential projects. Inevitably they begin by negotiating existent structures and dominant ideas of film production both within their cultures and outside of them.

The circulation of ideas should take place alongside training to make films; theoretical considerations can also have a vital role. The encouragement of thinking about and through film must be radical and pluralist – the openness to the free movement of speculation should release curiosity, challenge supposition, develop dissent. My initiation to theory took place when the interface between structural approaches, centred on psychoanalysis, semiology and Marxism, constituted in the 1970s and 1980s. This encounter was founded on the notion that all these ideas were reflexive – not fixed dogmas – configurations which would change and evolve in new historical conjunctions and they would continue to develop.

We should also look at how institutions currently configure creative and academic activities in film training – what interception and interaction between these categories is possible or productive? The theory and practice divide which bedevils European higher education needs to be challenged in all its institutional versions, we must re-invent the ways that the activities of making and thinking interact. The artistic mode of thought permeates and dissolves the edges of both academic discourse and craft-based training. Hannah Arendt described Benjamin’s ‘poetic thinking’ (1973: 50), in the unfinished Arcades Project he had begun applying collage techniques to literature, deploying fragments and quotations in an inventive attempt to understand everyday life historically. This, like Godard’s equivalent work in film, Histoire(s) du Cinema (Switzerland, 1988-1998), encourages curiosity about issues to which no verifiable knowledge is possible. As Arendt put it, ‘Meaning and truth are not the same’ (Quoted in Wesseling, 2011: 9). Artistic knowledge is consonant with Julia Kristeva’s description of abjection: ‘What disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite’ (1984: 4).

The relationship between ethics and aesthetics is rarely referred to in the understanding of filmmaking. But in a 1959 article for Cahiers du Cinema Luc Moullet suggested that ‘Morality is a question of tracking shots’, a phrase which was repeated and inverted shortly afterwards y Jean-Luc Godard: ‘Travelling shots are a question of morality’ or ‘Politics is a travelling shot’ (Ebert, 1969). This is exemplified in the virtuosic sequences in Soy Cuba (Mikhail Kalatozov, USSR/Cuba, 1964) which, like Que Viva Mexico (Sergei Eisenstein, USSR, 1930) before it, engaged Soviet filmmaking with Latin American politics. These unexpected formulations indicate the movement between formal and ethical considerations emerging from the debates taking place around the French New Wave; an intensity of ideas was shaped in relation to a fresh constellation of filmmaking as freewheeling low budget fiction features were realised alongside new variations of documentary form such as cinema verité. Regrettably the narrower approaches of most current filmmaking courses often place their emphasis on technical training for the industry and exclude political or critical thinking. It is an instrumental, craft-based approach which does not create space for the necessary imaginative engagement and understanding of the broader social importance of film and television. A modern pedagogy should propose that critical analysis and production be continuously connected and interactive.

The ethics that need to be embedded in training lead to questions such as: what role can filmmaking have in the repair of the condition of humanity? What behaviour helps or harms sentient creatures? How should filmmakers conceive of ethics and their responsibility for the other? Do we need to remind ourselves that there is a point to making the moving image? Radical approaches to the reformation of filmmaking and systems of communication are crucial if we are avoid the dangers inherent in neglecting a moral human compass with respect to our engagement with each other, the natural world and potential technological ‘progress’.

The industrial approach leads some film schools to feel that it is appropriate to propose the production of imitation commercials as a training exercise. This is consonant with the growing sector of film schools which are commercially operated and privately owned. A relentless opportunism pushes aggressive and commercial forces forward in sectors which were previously protected (like education and health) as they were understood as central to communal interests. Rather than replicating the culture of advertisements, we should work to encourage critical and independent thought. The spaces of education should offer opportunities to assess the impact and implications of consumer culture, not reinforce it. A modest initiative at the Huston School of Film & Digital Media involves teams of students on the MA in Public Advocacy and Activism preparing briefings for those on the Production and Direction programme, setting out ideas that can be treated imaginatively in their realisation by the filmmakers. Thus the two groups of students collaborate and focus on changing public opinion through short films.

The political dimensions to education involve the explicit assumption of social responsibility. We should always think of the audience and ask ‘What do we make films for?’ Suggested designs for working in film connect with living and effecting the outside world – the point is to change it! As Paulo Freire (1996) indicated in his seminal book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, a continued shared investigation between teachers and students can lead to new awareness of selfhood, forms of criticism and radicalisation that set in motion engagement in the effort to objectively transform concrete aspects of the social formation.

It is important for students to develop a sense of wide-ranging formal possibilities and choices, including familiarity with film from the past and from other cultures, creative documentaries and experimental, visually-based work. There is a centripetal pull towards dominant forms of filmmaking which must be countered if there is to be the possibility of a diversity sustaining and celebrating strong indigenous cultures around the world.

The urgency of ethical issues may depend on the place from which you speak. Whatever the differences between Africa, Asia or Latin America, they are connected to critical and insubordinate perspectives outside the West. In Africa, Latin America and Asia films from other continents and cultures in the South may be especially relevant; I remember showing Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, Algeria/Italy, 1965) at the Hanoi Academy of Theatre and Cinema in Vietnam in 2005 and the students responded to the film with exclamations of “But that’s our story!”

The use of the phrase ‘developing world’ is a euphemistic shadow of the non-Politically Correct (PC) term ‘underdevelopment’ – contact with the global South should lead to self-examination in ‘the overdeveloped world’, and lead to serious consideration of the perilous situation to which Western societies have brought the Earth as a whole. In the long term an economic system predicated on growth and accumulation cannot continue on a planet of limited resources. We have created a scale of prosperity and a consumerist lifestyle which makes disparity and injustice inescapable. Thus aspects of the ‘underdeveloped’ may in fact be ahead of facets of societies that are ‘overdeveloped’ and which will soon need to retract from the economy of perpetual growth.

The development of digital technologies provides fast changing possibilities for film students to develop their own work, in the way it is made and also in the way it is distributed. New forms of rapid access to information and other audio-visual material open stimulating new perspectives and an abundance of alternative forms. This may have especial emancipatory potential in places where expensive capital equipment is limited. In various subject areas of the academic domain creativity is increasingly combined with criticism, production with analysis; supporting the development of audio visual and critical practitioners in many different disciplines.

However we should not overestimate the role of technology or the potential of new digital implements. The use of the internet and social media builds networks quickly but, as activist tools, they function more for participation than motivation (Gladwell, 2010). The politics of representation leads to the re-presentation of politics – the confidence of the self-centred West assumes that its own technology must have led to social change in other places; Silicon Valley in California somehow unconsciously assumes that it had a key role in initiating social change in Tunis or Cairo. Although young people using social media played a leading role it is not accurate to describe the Arab Spring as a ‘Facebook revolution’ or twitter-led phenomena (Bergen, 2012: 260). Electronic communications facilitated by portable digital media do not determine social action, they support it and indicate potential for interaction through the internet and social networking tools. In the post-war period the AK-47 played a role in many social upheavals that it neither initiated nor led.

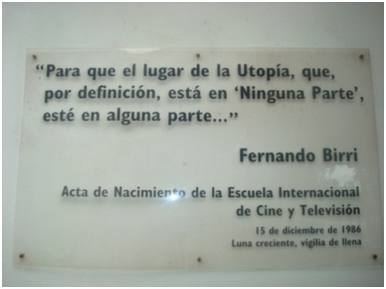

Cultivating filmmakers, as the agricultural term suggests, involves nourishing and enlightening new generations, taking them towards a refreshed social and aesthetic function for the moving image. Enabling them to think flexibly and strategically outside of the acquisition of technical skills is crucial – technique is a tool and not a goal. There can be a displacement of attention, which makes a fetish of new equipment; it is important to remember that a much better film can be made with intelligent and imaginative ideas on basic equipment than many a specious short shot on an expensive camera and edited with sophisticated software. The catalytic function of art for curiosity, intelligence and emotion moves it towards the possibilities of invention, dissent and social intervention. Invoking Nietzsche, Barthes argues that imagining new ways of teaching film is part of the attempt to find new ways of thinking and new ways of living (1985: 93). Argentinean filmmaker Fernando Birri’s graceful formulation is inscribed on a plaque in the entrance to the Cuban Film School in Havana: ‘So that the place of utopia, which by definition has no place, has a place...’

Note: This short article originated from a talk originally given as part of the symposium ‘Imagine quel future pour l’ensignement du cinema?’ at the Imagine Institute in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso on 26 February 2013. Photo courtesy of Nicholas Balaisis.

References

Arendt, H (1973) ‘Introduction’ in W Benjamin Illuminations, London: Fontana.

Barthes, R (1985) Grain of the Voice, London: Jonathan Cape.

Bergen, P (2012) Manhunt, London: Bodley Head.

Ebert, R (1969) Review of Weekend, available: http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/weekend-1968 (accessed 19 December 2013).

Freire, P (1996) Pedagogy of the Oppressed, London: Penguin.

Gladwell, M (2010) ‘Small Change’, The New Yorker, 4 October 2010, available: http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/10/04/101004fa_fact_gladwell (accessed 13 December 2013).

Kristeva, J (1984) Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, New York: Columbia University Press.

Moullet, L (1959) ‘Sam Fuller: In Marlow’s Footsteps’, Cahiers du Cinema, March 1959.

Petrie, D & Stoneman, R (2014) Educating Film-makers: the Past, Present and Future, Bristol: Intellect Books.

Stoneman, R (2013) ‘Global Interchange: the Same, but Different’ in M Hjort (ed.) The Education of the Filmmaker in Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stoneman, R (2012) ‘“Isn't It Strange that ‘World’ means Everything Outside the West?” an interview with Rod Stoneman’ in W Higbee & S M Ba (eds.) De-Westernising Film Studies, London: Routledge.

Trafic (2004)‘Qu’est-ce que le cinéma?’ Trafic, No. 50, Summer 2004.

Wesseling, J (ed.) (2011) See it Again, Say it Again, Amsterdam: Valiz, 2011.

Rod Stoneman is the Director of the Huston School of Film & Digital Media at the National University of Ireland Galway (NUIG). He was Chief Executive of Bord Scannán na hÉireann/the Irish Film Board until September 2003 and previously a Deputy Commissioning Editor in the Independent Film and Video Department at Channel 4 Television in the United Kingdom. In this role he commissioned, bought and provided production finance for over fifty African feature films. His 1993 article ‘African Cinema: Addressee Unknown’, has been published in six journals and three books.

He has made a number of documentaries, including Ireland: The Silent Voices, Italy: the Image Business, 12,000 Years of Blindness and The Spindle, and has written extensively on film and television. He is the author of Chávez: The Revolution Will Not Be Televised; A Case Study of Politics and the Media (2008); and Seeing is Believing: The Politics of the Visual (2013).