Migration Stories North West and Global Education: Perspectives from a Community Heritage Project

Development Education and Migration

Abstract: Drawing on the methodology and preliminary observations of a Heritage Lottery-funded project, we evidence how community heritage can promote global learning. Migration Stories North West (2021) is led by an interdisciplinary team of global education practitioners, artists and academic historians, and shaped by the interests and contributions of the adult and youth participants who have sought out stories of over a hundred individuals who have moved in or out of North West England from ancient to contemporary times. These stories, documented on an interactive online map, give migration a human face and a local connection. They capture the multiple drivers that influence relocation, reflect the contributions individuals made to their host societies, both mundane and exceptional, and reveal the impact of legislation in shaping migration patterns and migrants’ lives. Researching the stories led participants from the local to the global, and from the past to the present to the future, fostering a sense of solidarity that stretches not only across space and place but across time. In this way, it helps to respond to the call by the Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures Collective to challenge ‘(delusions of) separation’ (n.d. a). Participants have uncovered for themselves narratives that challenge anti-migration rhetoric such as the long-standing hybridity of their localities. The temporal span has also encouraged both reflective distance and contemporary comparison (Santisteban, Pagès and Bravo, 2018). Presenting the stories on the interactive map enables viewers to explore the data following their own interests, but they cannot help but encounter a sum greater than its parts. Our methodology fosters perspective consciousness, cross-cultural awareness, and appreciation of individual choice and agency (Bentall, 2020), and is readily replicable. These qualities illustrate the alignment between heritage work and the values of global education, inviting new ways of conceptualising migration - of self and other in the world - with hope, inspiration and learning (Bourn, 2021).

Key words: Migration Histories; Community Heritage; Solidarity; Global Education; Learning Resources; Collaborative Approaches.

Introduction

Migration Stories North West (2021) is a three-year National Lottery Heritage Fund project (2021-24), led by an interdisciplinary team of global education practitioners, artists and academic historians in the North West of England. The partnership is working with adult and youth volunteers to research stories of people who have migrated in and out of our region from the Roman era to the present day and collate these stories on an interactive digital map. In a period of increasing hostility towards migrants, the explicit aim of our project is to normalise migration by showing its long and diverse history, while also highlighting some of the many interconnections between our region and the rest of the world. In this article, we discuss our model of community heritage practice, reflect on the connections between the disciplines of history and global education, and point to ways in which our approach promotes global learning. The idea that a community heritage project could exemplify global education in practice is perhaps not an entirely obvious one, but we suggest that exploring the social, political and economic realities of the past helps our project participants better understand the challenges of today as well as the possibilities for the future. Specifically, our project supports the Dublin Declaration’s definition of global education as an approach which ‘enables people to reflect critically on the world and their place in it’, ‘opens their eyes, hearts and minds to the reality of the world at local and global level’ and ‘empowers people to understand, imagine, hope and act’ for a better world (GENE, 2022: 3).

Background

Migration Stories North West (NW) (2021) is the latest in a series of community heritage projects led by Global Link Development Education Centre (DEC) in Lancaster, North West England, and is being delivered in collaboration with four other North West organisations: Cumbria DEC, Cheshire Global Learning, Crossing Footprints Community Interest Company (CIC) in Manchester and Liverpool World Centre. It is supported by consultant historian, Professor Corinna Peniston-Bird from Lancaster University, a long-time collaborator on Global Link’s heritage works. The project builds on our now well-developed practice of working with adult and youth volunteers, supported by historians, museums, archives and other heritage organisations. Through our work we research and document more ‘hidden’ local (hi)stories with the aim of using them as a way to shed light on wider, global stories about the ongoing struggle for rights and social justice. Previous projects have focused on, for example, LGBTQ+ histories, women’s suffrage and activism, religious and political dissenters, and histories of peace and internationalism. We have learnt from participants in these previous projects how inspiring it can be to learn about people from the past who have worked towards shared goals and how this can promote a sense of solidarity and hope, spurring ideas for action and change today and in the future.

Migration Stories NW emerged specifically from a desire to counter negative narratives about migration kindled by the current ‘hostile environment’ (Yeo, 2018). Eten has argued (2017: 48-49) that as ‘anti-immigration sentiment’ grows in the global North, there is a lack of attention to the ‘complex push factors’. As we will see below, these push factors are made implicit in this project through the wide-ranging stories collected and presented. As one of our project participants commented, ‘We only hear the stories told without ownership by the right wing press or we hear only of those who died en route and it is never a complete or sympathetic story’. Parejo et al. (2021: 1) note that at the present moment, as the world experiences one of ‘the most important moments of massive human movement since the Second World War’, the language of ‘us and them’ is increasing with migrants associated with ‘negative issues and problems’. Devereux (2017: 2) agrees that migrants are persistently ‘othered’ in the media, arguing that the language of ‘refugee crisis’ as opposed to ‘humanitarian crisis’ identifies migrants as the source, rather than an outcome, of the problem with little coverage as to why people are migrating. Through its focus on detailed narratives of real individuals, our project has encouraged instead an awareness of the complexities of migration and a sense of shared humanity (Golden and Cannon, 2017).

There is an emphasis in the literature on how global education can offer both a critical and positive lens on the very challenging topic of migration – critical, through taking ‘an historical and global view of development processes’ (Eten, 2017: 49), and positive, by helping to challenge mainstream media narratives and contribute to more inclusive societies (Devereux, 2017: 1; De Angelis, 2021: 71; UNESCO, 2018: 7). As Akkari and Maleq (2020: 8-9) note, exploring migration through the lens of global citizenship can help to challenge ‘binary notions of us and them and here and there’. Migration poses challenges that global education can ‘turn into opportunities’ rooted in values of human rights and social justice (De Angelis, 2021: 56). De Angelis argues (2021: 72) for work that brings ‘formal, non-formal education and local realities together’ by ‘integrating migration issues and migrants’ stories within the school curriculum’. Below we outline our approach to community heritage work that aims to make these connections by creating opportunities for thinking and learning about the world today, in both formal and non-formal contexts, through engagement with local migration (hi)stories.

There is an existing body of useful and well-researched, historically based, global education tools and resources developed by practitioners across The Global Learning Network, a practitioner network of Development Education Centres (DECs) across England of which three of the Migration Stories NW partners are members. These resources – such as ‘Global Stories’, developed by Reading International Solidarity Centre (RISC) (n.d.) – use migration as a lens through which we can understand wider social, political and economic complexities. There is also a teacher training course on migration developed by Global Learning London (2023). These are particularly rooted in work that could be described as decolonising the curriculum and anti-racist practice. Whilst much of the reasoning underpinning the work may be similar to Migration Stories NW, there are explicit differences in our approach: as a community heritage project, our method can be more open and participant-led. In particular, we involve our participants (both adults and young people) as fellow researchers in the way advocated by Parejo et al. (2021: 3), contributing actively to knowledge building about migration history and having a voice on the way the content develops and thus the stories it reveals.

Project methodology and outputs

By discovering stories of individual women, men and children who moved in or out of our region from the distant past to the present day we aimed to highlight how the North West of England – like the rest of the UK – has always been a place of migration. The historical dimension was a deliberate emphasis, taking up the challenge voiced by Parejo et al. (2021: 1) that:

“However obvious it might be that the mobility of people through territories is not a novelty, this must be restated, given the emergence of discourses that attempt to justify the adoption of measures against migration that go against human rights based on territorial and nationalist criteria”.

Moreover, we hoped that the stories would demonstrate the positive impact of migration on place, shaping what the North West has become today and how it will continue to develop in the future. To challenge the prevalence of ‘us and them’ rhetoric, it was vital that we considered stories of both immigrants and emigrants and showed migration to and from other parts of the UK as well as other countries. The intent was that migration was not represented as a modern phenomenon, was not assumed to be unidirectional, and that the outputs did justice to diverse motivations and experiences of migration without claiming ever to be fully representative.

The project was designed in three cumulative stages:

In year one, each of the five regional partners recruited a group of local adult volunteers to research and write up stories of individual migrants from the Roman period to the mid-twentieth century. There was no expectation that specific themes should determine the volunteers’ choices, rather that their starting place should be curiosity: how did my grandmother come to move here, or, who was the first professional Black footballer in Britain? Each group visited local archive offices and museums, consulted online databases including Ancestry and the British Newspaper Archive, and held regular meetings to discuss research ideas and progress.

The project team read and commented on every story, looking in particular for two dimensions: was every point made substantiated by evidence? And did the narratives do justice to the people whose lives were being explored? Those two issues were related: in first draft many of the stories were lists of evidence; what grew was the ability to weave the facts into a substantiated narrative. From a skills perspective, volunteers commented on having learnt, for example, ‘how to search, how to use different sources, how to put our ideas together, link and express them’. But in terms of the subject matter, feedback suggested the powerful potential of this approach to encourage ‘perspective consciousness’ (Hanvey, 1982: 162-3), that is to say, ‘being awakened to one’s own unique perspective and its limitations’ (Baker and Shulsky, 2020: 5f). We discuss this below.

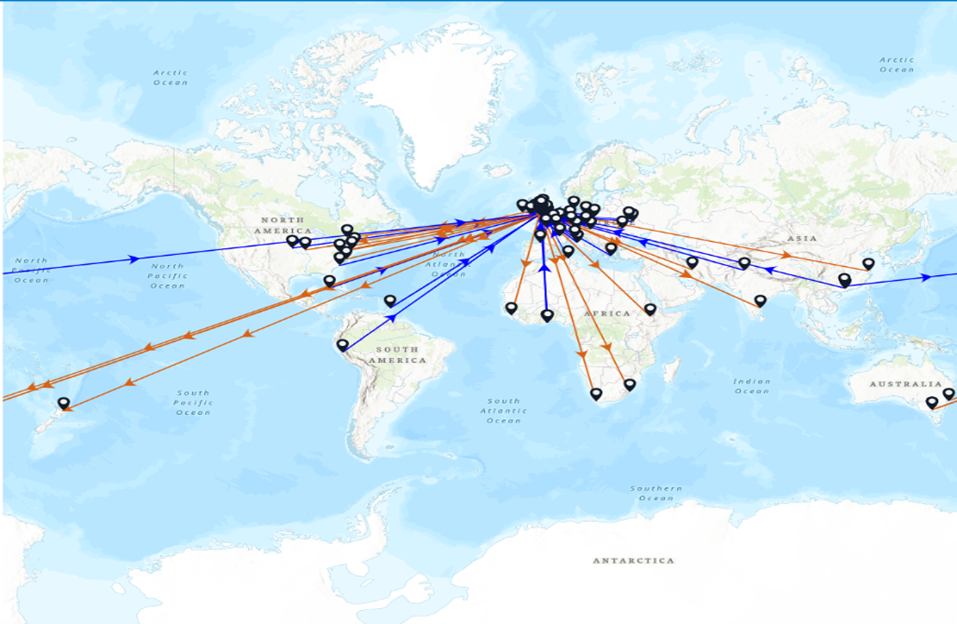

The stories uncovered by the volunteers are presented digitally using ArcGIS ‘storymapping’ software, capturing both the many comings and goings that traverse our part of England and also the region’s connection to locations across the globe (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Migration Stories NW map (zoomed out view).

The visual and interactive nature of ArcGIS draws in the reader to discover individual stories through detail – a face, a place, a date – while at the same time allowing the viewer to ‘zoom out’ and get an immediate sense of the global nature of migration. We also built in keywords which allow viewers to search the stories for certain time periods or themes, including traditions, food and customs, climate and landscape, adventure and opportunity, or war, conflict and uprising. The presentation of the data through a map encourages geo-literacy, with its focus on interactions, interconnections and implications (National Geographic, 2023), a sense of shared humanity across space.

By the start of year two of the project, the interactive map featured around sixty stories of individual women, men and children from every continent and spanning the first to the twentieth century. Each partner then used this map as the basis for a series of global education workshops with local schools, extending the pupils’ knowledge and understanding of migration through an exploration of the stories and of their own ideas, perspectives and preconceptions around migration. Following the initial workshops, the partners went on to train the pupils, aged nine to seventeen, in how to conduct oral histories. Each of our five regional groups then conducted ten interviews in their schools with people who have moved in to their locality, either face-to-face or on Zoom. These interviews are being edited into digital, audio-visual stories and added to our interactive map, extending its temporal range to the present day.

When working with the schools, we set out clear learning outcomes in our workshop plans in relation to knowledge and skills development. Alongside our global education focus, we also identified some specific links to the English national curriculum subjects of History, Geography, English, Citizenship and Spiritual, Moral, Social and Cultural Development (SMSC), demonstrating the potential for integrating migration issues and migrants’ stories within the school curriculum to enhance particular learning objectives. It is important to note here that while there is value in global education practitioners exploring particular aspects of history, we did not explicitly set out to teach ‘History’ in creating our intricate web of stories, focusing more on individual journeys of discovery rather than predetermined content. The stories are intended to open up curiosity and inspire further research, and indeed to introduce through subjective narratives the question of what constitutes ‘fact’. Interestingly, whilst this is our approach, there are multiple examples from pupils’ evaluation showing that they have enjoyed learning new historical information and were curious to learn more about a wide range of eclectic issues (from the existence of the Iron Curtain to that of a city called Bethlehem in the United States).

The focus of the project in year three is shifting towards evaluation and dissemination, including the development of a global learning resource for schools based on our map, the creation of three short films promoting the project and its outputs, and the production of a pop-up exhibition to tour around our region, bringing the stories to a wider audience. The exhibition will use a range of outputs and associated activities to engage and promote the work more widely. Within all of this, the multidisciplinary nature of the team has been of enormous importance. The role of the consultant historian on the project has been not to act as expert on the topic, but to encourage breadth and depth of coverage to counterbalance the emphases of the conventional archive, to offer training in archival and oral research, and to support the regional partners as they and their volunteers encountered the unfamiliar. The merits of creative and curatorial projects involving ‘citizen historians’ and ‘citizen cartographers’ have been extensively discussed in the field (see, for example, Lilley, 2017). The historical underpinning of the project was essentially about rigour of practice: ensuring that every story was rooted in primary and secondary evidence, and that absences in the historical record were also reflected. Although most partners have worked on heritage projects before, for all except Global Link this was the first time working with archives to conduct and write up original research and for several partners it was also their first oral history project.

Feedback from both the adult and youth volunteers suggests they have particularly appreciated the investigative process, one adult noting that what they had enjoyed about the project was ‘the research, both online and in person, especially Carlisle Archive and the British Library’ and making wider contacts such as the ‘Museum of the City of New York’. A youth volunteer commented that they had most enjoyed ‘asking people why they have made decisions to come to Britain – often it is seen as a conversation to avoid but it has been really beneficial as a young person to see what motivates or forces people to move’. There was a clear skills development aspect to the work: archive research, use of primary sources, interviewing, referencing, editing, copyright and more. As one volunteer noted, ‘the rigour of the referencing and editing’ was ‘good discipline!’. Moreover, the emphasis on volunteer choice and engaging with individual lives encouraged a deeper critical literacy. The intention was that expertise was co-created by all participants in the project. Participants could uncover for themselves any challenges to current preconceptions and emphases in public discussions of migration - and frequently did, as the participant voices included here evidence.

Findings

The (inter)disciplines of history and global education

This project accommodated paradox: the selection of individual stories never claimed to be representative and yet our map presents a picture of the diverse dimensions of migration that is greater than the sum of its parts. As one of our adult volunteers commented, ‘It made me realise that every person’s migration story is unique and carries valuable lessons for others to learn from’. Anchored in the local, Migration Stories NW encouraged openness to the global; rooted in the past, it provoked analysis of the parallels and departures between the past and the present, and the notion of potential futures (Santisteban, Pagès and Bravo., 2018). One volunteer noted that they had particularly enjoyed ‘connecting people and places through time’. The temporal dimension of global education is often future-focused - the ability to envision and therefore strive towards a better future (e.g. Hicks, 2016). This can overshadow the parallels between historical research and the goals of global learning, the importance of understanding how our ‘now’ is the product of our past.

The overlap between the discipline of history and global education should not be overstated. Bourn (2021: 66) also argues that global learning rests on ‘a sense of optimism that change is possible based on informed learning that can encourage movements towards a more just world’. Historians are not necessarily optimists, narrating the past as either progressive or declensionist: as William Cronon (1992: 1352) describes, the plotline:

gradually ascends toward an ending that is somehow more positive – happier, richer, freer, better – than the beginning [or] the plotline eventually falls toward an ending that is more negative – sadder, poorer, less free, worse – than the place where the story began.

Global education principles challenge historians to reflect on the visions of the world they are co-creating, a provocation that sits well beside other central themes in the discipline, such as de-colonisation. This shift addresses cultures of exclusion and denial, seeks to open up new spaces and reflect more critically on the production of knowledge. As Atkinson et al. noted there is ‘an increasingly “global” university History offer’ (2018: 26).

Within the search for social justice, anti-racist practice and de-colonised curricula, there is a need to ask ourselves who is not in the room (Abdi, 2020). In this project we are seeking to bring such individuals into the room (although we acknowledge that only those who have left a trace in the historical record, however faint, are represented within the pre-1950 written histories). Even initiating conversations about these gaps in the historical context with our volunteers has opened their thinking about who gets to speak, where and how. For our heritage volunteers to consider piecing together the stories of those less documented individuals was a step forwards in critical thinking and perspective consciousness. As one adult volunteer explicitly noted, ‘I particularly liked the fact that we found the ordinary people as well as the privileged entrepreneurs’.

All history engages with the interplay of space and time, the significance of temporality, continuity and change. The topic of migration is ideal to meet Bourn’s (2021: 69) challenge that ‘a crucial role of [global] education should be to encourage engagement in the complexity of issues, and the need to go beyond emotional responses to recognition of forces that affect processes of social change’. One argument of this perspective is therefore not only that heritage projects and the support of academic historians is added value to global education but that the values of global education challenge the discipline of history. Like all meaningful interdisciplinary work, all parties are transformed by each other.

GCE Otherwise?...

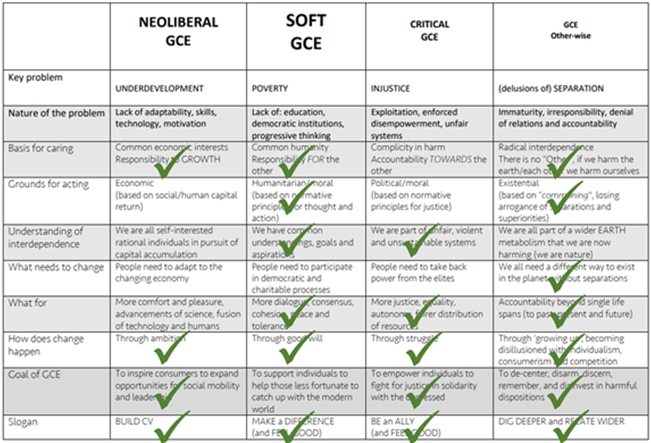

We are still in the delivery phase of this work and have therefore not yet undertaken exhaustive analysis of evaluation data. However, we are able to share our emerging thinking around the ways in which we are conceptualising this work. Of the many frameworks available to global education practitioners, the ‘GCE [Global Citizenship Education] Ideascapes’ of the researchers and artists collective Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures (n.d. b) has best allowed us to reflect on the different dimensions of Migration Stories NW. Figure 2 shows our assessment of the project against their tabulated ‘Four Approaches to GCE’ (Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures, n.d. a).

Figure 2. Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures: ‘Four Approaches to GCE’ with the assessment of our project marked in green ticks.

Exploring the four ‘key problems’ identified in that table as the root of differing approaches to GCE, Migration Stories NW most closely aligns with what is described as ‘GCE Otherwise’, the key issue dealt with being ‘(delusions of) separation’. Although within our individual stories all of the key problems identified (underdevelopment, poverty and injustice) may be touched upon, the creation of our project map helps start to unpack the concept of ‘the Other’ and challenge the illusion of essential difference between different geographical and ethnological communities. In ‘GCE Ideascapes’ (Ibid.) the authors highlight that ‘Social cartographies are educational instruments that are not meant to describe or prescribe things, but to be a stimulus for different conversations about intersections that are usually not talked about’. The map presents a simple starting point for our participants and the wider viewing public to visualise and explore ideas of interdependence in a way that reflects global education aims. To begin a journey that inspires us to question our ‘arrogance of separations and superiorities’ (Ibid.) in such a straightforward and accessible way is, we argue, an enormous achievement of this work. It is not a new idea that through the exploration of history we can come to understand poverty and injustice in the world today. However, to map and thus begin to understand how past, present and future are economically, politically and socially inextricable effectively addresses the problem of ‘(delusions of) separation’.

It should also be noted here that some of the above impact in terms of what might be described as systems thinking and understanding also applies to some of the teachers with whom the project partners have worked. One teacher, for example, noted that the stories highlighted the impact of migration ‘in terms of e.g. the culture, diet, religion, legal systems etc of both our region and the wider world’. This supports Eten’s suggestion that a GCE approach to migration serves to highlight the ‘permeability of all cultures and citizenship beyond national polities’ (2017: 59) and indeed at local level. Similarly, one adult volunteer came to recognise the long-standing hybridity of their region, noting that their region (Cumbria) was not nearly as historically homogenous as conventionally represented, while another from the same region became aware of the disjuncture between their research and the representation of the region by ‘right-wing factions’ as a ‘last bastion of Englishness’. These interim observations support the argument by De Angelis (2021: 61) that the multidimensional approach of global education can help ‘unpack definitions of migrant and migration’ and promote the notion of ‘intercultural citizenship’ (Ibid.: 64), which embraces difference while understanding interconnectedness at a local, global – and indeed, glocal – level.

What seeing the world through the eyes of so many others has done, is to inspire a sense of solidarity and curiosity, alongside an openness to otherness and dialogue. In fact, inspired by the work of Biesta (2006), Bruce argues that ‘learning ought not to be about the acquisition of knowledge, skills and attitudes at all, but rather a project of coming into the world, where the world is (engaging with) the Other’ (2013: 39). Equally, the work of Bruce (Ibid.: 45), for example, clearly outlines how encounters with others and post-critical conceptual frameworks take us ‘beyond the imperialist projects of benevolence, paternalism, and the ‘helping imperative’. The project goes some way towards answering questions of what it means to be human, and in agreement with Biesta’s work, suggests that this question is one to answer together through education, not before education can start.

It is useful to global education practitioners to be aware of what is accessible and palatable for educators working within statutory and formal education systems. This also applied to our adult volunteers in year one, some of whom may have initially joined the project because of their interest in heritage and history, as opposed to any wider social justice concerns. The emerging sense that this unique combination of history, heritage and migration supports a move towards ‘GCE Otherwise’ is of enormous value to the project team, and perhaps to the wider sector, addressing the ‘local to global’ objectives which we often hold in common.

Conclusion

The stories we have discovered through this project are rich and diverse and sometimes surprising: they encompass a range of push and pull reasons for migration including conflict, conquest and colonialism as well as the search for economic or educational opportunity and adventure. They reveal the way migration shapes language and culture as well as influencing the work we do, the food we eat and the clothes we wear. The focus on the past creates some distance from contemporary preoccupations and assumptions, but in so doing encourages greater awareness of the present not as a given, but as only one possible outcome of choice and happenstance. The contemporary interviews challenge generalisations and stereotypes, suggesting the intricacies of lives behind the headlines.

Fundamentally the stories also show how migration forges connections within and across different places, spaces and times and, by their very individual nature, invite us to find points of connection between our own lives and those of others, countering delusions of separation. The focus on individual stories worked against the over-simplification of complexity that typifies reiterations of prejudice. As Cronon argues (1992: 1370):

“As storytellers we commit ourselves to the task of judging the consequences of human actions, trying to understand the choices that confronted the people whose lives we narrate … In the dilemmas they faced we discover our own, and at the intersection of the two we locate the moral of the story”.

The model the team has developed for this project is entirely replicable in a range of scenarios and can be taken as a move towards developing best practice for those seeking to explore global education through community heritage. The tangible links this work creates between the local and global hits many of our global education ideals and starts to move individual participants towards ‘GCE Otherwise’, that is, more critical reflection on the interconnected nature of the world around us.

References

Abdi, M (2020) ‘Narratives, Anti-Racism and Education’, In conversation with Dr. Muna Abdi, Consortium of Development Education Centres Annual Conference 2020.

Akkari, A and Maleq, K (2020) ‘Global Citizenship Education: Recognizing Diversity in a Global World’ in A Akkariand and K Maleq (eds.) Global Citizenship Education: Critical and International Perspectives, Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, pp. 3-12.

Atkinson, A, Bardgett, S, Budd, A, Finn, M, Kissane, C, Qureshi, S, Saha, J, Siblon, J and Sivasundaram, S (2018) Race, Ethnicity and Equality in UK History: A Report and Resource for Change, London: Royal Historical Society.

Baker, S and Shulsky, D (2020) ‘Planting the seeds of perspective consciousness: Creating resource sets to inspire compassionate global citizens’, International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 4-20.

Bentall, C (2020) ‘Editorial: The Policy Environment for Development Education’, International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 89-91.

Biesta, G J J (2006) Beyond Learning: Democratic Education for a Human Future, Oxon and New York: Routledge.

Bourn, D (2021) ‘Pedagogy of hope; global learning and the future of education’, International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 65-78.

Bruce, J (2013) ‘Service learning as a pedagogy of interruption’, International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 33-47.

Cronon, W (1992) ‘A Place for Stories: Nature, History, and Narrative’, The Journal of American History, Vol. 78, No. 4, pp. 1347-76.

De Angelis, R (2021) ’Global Education and Migration in a Changing European Union’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 32, Spring, pp. 55-78.

Devereux, E (2017) ‘Refugee Crisis or Humanitarian Crisis?’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 24, Spring, pp. 1-5.

Eten, S (2017) ‘The Role of Development Education in Highlighting the Realities and Challenging the Myths of Migration from the Global South to the Global North’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 24, Spring, pp. 47-69.

GENE (Global Education Network Europe) (2022) The European Declaration on Global Education to 2050: The Dublin Declaration – A European strategy framework for improving and increasing global education in Europe to the year 2050, Dublin: GENE.

Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures (n.d. a) ‘Four Approaches to GCE’, available: https://decolonialfuturesnet.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/gce-table-4-app... (accessed 6 December 2023).

Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures (n.d. b) ‘GCE Ideascapes’, available: https://decolonialfutures.net/gce-ideascapes/ (accessed 15 December 2023).

Global Learning London (2023) ‘Shared Ground: a CPD for schools on teaching about migration’, available: https://globallearninglondon.org/training-consultancy/sharedgroundcpd/ (accessed 12 December 2023).

Golden, B and Cannon, M (2017) ‘Experiences, Barriers and Identity: The Development of a Workshop to Promote Understanding of and Empathy for the Migrant Experience’, Policy and Practice: A Development Education Review, Vol. 24, Spring, pp. 26-46.

Hanvey, R G (1982) ‘An Attainable Global Perspective’, Theory into Practice, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 162-67.

Hicks, D (2016) A Climate Change Companion: For Family, School and Community, Teaching4abetterworld.

Lilley, K D (2017) ‘Commemorative cartographies, citizen cartographers and WW1 community engagement’ in J Wallis and D Harvey (eds.) Commemorative Spaces of the First World War: Historical Geographies at the Centenary, London: Routledge.

Migration Stories North West (2021) available: https://www.migrationstoriesnw.uk (accessed 15 December 2023).

National Geographic (2023) ‘What is Geo-literacy?’, available: https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/what-is-geo-literacy/ (accessed 6 December 2023).

Parejo, J L, Molina-Fernández, E and González-Pedraza, A (2021) ‘Children’s narratives on migrant refugees: a practice of global citizenship’, London Review of Education, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp.1-29.

Reading International Solidarity Centre (RISC) (n.d.) ‘Global Histories: a teaching resource for KS2-4’, available: https://risc.org.uk/images/education/resources/global-histories/global-histories-overview.pdf (accessed 12 December 2023).

Santisteban, A, Pagès, J and Bravo, L (2018) ‘History Education and Global Citizenship Education’ in I Davies, L-C Ho, D Kiwan, C L Peck, A Peterson, E Sant, Y Waghid (eds.) The Palgrave Handbook of Global Citizenship and Education, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.457-72.

UNESCO (2018) Global Education Monitoring Report Summary 2019: Migration, Displacement and Education – Building Bridges, not Walls, Paris: UNESCO.

Yeo, C (2018) ‘Briefing: what is the hostile environment, where does it come from, who does it affect?’, available: https://freemovement.org.uk/briefing-what-is-the-hostile-environment-whe... (accessed 12 December 2023).

Alison Lloyd Williams is the heritage projects coordinator at Global Link DEC in Lancaster. She has ten years’ experience of working with adults and young people, using engagement with local history as a stimulus for critical reflection on global issues.

Corinna M Peniston-Bird holds a Chair in Gender and Cultural History in the Department of History at Lancaster University. Since 2013 she has collaborated on numerous community heritage projects, and led an impact case study considering local, inclusive and historically-driven commemoration that included mapping.

Karen Wynne is co-director of Liverpool World Centre. Karen has worked across local communities in the arts, non-formal education, and migrant support for over twenty years, and has a particular interest in social justice themes within global education.