How can Migrant Entrepreneurship Education Contribute to the Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals? The Experience of the Fresh Start Programme

Development Education and Climate Change

Abstract: This article considers the implications of migrant entrepreneurship education (MEEd) for sustainability and for the work of global adult educators. It will present some insights into the opportunities and challenges created by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through the experience of running the Fresh Start (FS) MEEd programme. This programme, funded by the European Union (EU) in 2017-2019, brought together teams from three countries - the Netherlands, the United Kingdom (UK) and Belgium - and involved three universities: Zuyd University of Applied Sciences (Maastricht), London South Bank University (LSBU); and University College Leuven Limburg (UCLL) in the province of Limburg, Belgium. The team found that there is no ‘one size fits all’ as each context and each community have differing starting points and needs. Central to this is an approach which is learner-centred, enables participants’ voices to be heard, and supports the co-creation of the programme. Education and learning are always a two-way process and migration offers us all an opportunity to learn from each other and to appreciate the rich resource of ideas and skills which migrants have to offer communities.

The first section of the article provides an overview of the implications of migration for sustainability and its relationship to delivery of the SDGs. Section two examines the FS MEEd programme as a model for working with adult refugees and migrants. It presents some of the opportunities and challenges for educators created by the SDGs. Section three provides illustrations from the work of the FS MEEd programme and section four considers some implications and ways forward.

Key words: Migration; Refugees; Entrepreneurship Education; Sustainable Development Goals; Social Cohesion; Integration; Intercultural Awareness, Co-creation and Learning.

Introduction

Migration caused by conflicts or natural disasters often poses immediate challenges to sustainability, for the migrants themselves, for the countries they have left and for the countries where they now find themselves. Without addressing these challenges, it is not likely or possible to achieve the global goals for a sustainable world (UN, 2020). At the local level, migrants and refugees have a strong desire to contribute to the host society and to integrate effectively but there are many internal and external barriers to this. Migrant entrepreneurship education (MEEd) can help migrants contribute to their local communities and to their own well-being by developing their entrepreneurial ideas into businesses or employment. Entrepreneurial education has developed as part of a response to the need to develop a new generation of entrepreneurs as set out in the European Union’s Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan (European Commission, 2020). In recent years, the EU has extended this out to address the potential for refugees and migrants in order to harness their wide range of skills and talents which they bring and to develop their employment opportunities. The European Commission emphasises that entrepreneurship represents an alternative form of decent and sustainable employment for migrants. Indeed, there is evidence to indicate that migrants, especially first-generation males, can be more successful entrepreneurs than their peers in the host community (Ashourizadeh, et al., 2016).

Host community attitudes are at times driven by the mistaken belief that migrants are unwilling to work so MEEd programmes also provide opportunities to address negative perceptions and stereotypes, and to build more positive relationships. They can, therefore, contribute to the wider purpose of social cohesion, integration and social sustainability. The EU entrepreneurship competence framework (EntreComp) defines entrepreneurship as a:

“transversal competence, which applies to all spheres of life: from nurturing personal development, to actively participating in society, to (re)entering the job market as an employee or as a self-employed person, and also to starting up ventures (cultural, social or commercial). It builds upon a broad definition of entrepreneurship that hinges on the creation of cultural, social or economic value” (EU, 2016).

However, this fails to situate the framework within the context of environmental sustainability so MEEd has a responsibility to encourage participants to choose paths which safeguard and care for the natural environment. This illustrates the important role that the Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) can play within entrepreneurial education and in addressing the three pillars of sustainability: economic, social and environmental. Without ESD there is a likelihood that entrepreneurial education will not address the very real imperative of addressing climate change and the need to situate all activities within the carrying capacity of the planet.

Forced migration as a sustainability issue

According to UNHCR (2019), there are unprecedented movements of people across the globe owing to forced migration with 70.8 million forcibly displaced persons worldwide. Moreover, 85 per cent of the world’s displaced people are hosted by the poorest nations, with Turkey hosting approximately 3.7 million refugees; Pakistan 1.4 million; Uganda 1.4 million and Sudan 1.1. million (Ibid). The only high income, western country to come close to these totals is Germany with 1.1 million. Moreover, 57 per cent of refugees come from three resource poor countries, namely Syria, Afghanistan and South Sudan (Ibid). In high-income countries, there were in 2018 on average, 2.7 refugees per 1,000 national population but this figure is more than doubled in middle- and low-income countries, with 5.8 refugees per 1,000. And these figures do not take into account internally displaced persons globally – who are estimated at 41.3m (UNHCR, 2019).

The majority of refugees come from conflict-riven countries but there are many other causes of forced migration including natural disasters, unsustainable livelihoods owing to the effects of climate change, land grabs, pollution, and human rights abuses or persecution as a result of gender, religion, perceived dis-ability, ethnicity or sexuality. Many of the factors that force people to migrate are linked together and a systems’ approach is needed to address them. Hence the global partnership for the global goals (SDG 17, 2019) is becoming ever more important in order to address the imbalance of resources and power between and within countries. A number of recent conflicts have been exacerbated by the effects of climate change, for example, in Syria where large numbers of rural communities were forced to move to the cities because they were no longer able to sustain a livelihood on their land (Gleick, 2014). At the Spring 2019 meeting of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), David Attenborough, the renowned naturalist and broadcaster, warned that ‘Europe can expect even greater migratory pressure from Africa unless action is taken to prevent global warming’ and he warned policymakers that ‘time is running out to save the natural world from extinction’ (Elliot, 2019).

All these factors are, in effect, sustainability issues and if they are not addressed, the SDGs will fail to be delivered by 2030. Although forced migration receives very little attention within the SDGs, the forced migration of large numbers directly impedes their achievement. For example, one of the key causes of forced migration relates to the effects of climate change, which is causing land degradation, leading in many places to food shortages for local populations. This affects delivery of SDG 2 which aims to ‘End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture’ (SDG 2, 2019) which cannot be achieved without SDG 13 (2019) which aims to ‘Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts’. Thus, a holistic, joined up, systems’ approach by policymakers is essential in order to achieve the SDGs.

The effects of climate change alone are going to result in greater numbers of climate refugees and affected livelihoods (Brown, 2008). Indeed, this predicted that there will be between 50 and 200 million climate refugees by 2050 (Ibid: 11). The resolutions and decisions adopted by the Committee of the Whole of the United Nations Environment Assembly at its fourth session on 11 - 15 March 2019 noted that ‘business as usual’ is not an option and emphasised urgency of action. They recognised that the business and enterprise community have a great deal of potential to move towards a more sustainable economic model, for example, through adoption of a Green New Deal. However, the report focused mainly on international big business and did not acknowledge the immense energy and opportunity provided by small and medium enterprises (SMEs), non-profit and social businesses. And there is little or no attention paid in the report to education of any kind, hence the implication that these changes can be achieved in a top-down, implementation manner which is unlikely to be successful in the long term (Bowe, Ball and Gold., 1992; Binney and Williams, 1997). As Amina Mohammed, Special Advisor to the United Nations Secretary-General on Post-2015 UN Development Planning, stated:

“The greatest transformations will not be achieved by one person alone, rather by committed leadership and communities standing side by side …only through genuine collaboration will we see real progress in the new global sustainable development goals. Midwives, teachers, politicians, economists and campaigners must find common ground in their quest to achieve ground-breaking and sustainable change” (UNESCO, 2014).

MEEd and ESD – the FS model

ESD was developed after the 1992 Earth summit (UN, 1992) and linked the importance of environmental education (EE) and development education (DE) in order to address the needs of current and future generations. It integrated the concerns of development educators and environmental educators into a wider remit of education for sustainable development for the future of people and the planet. Forced migration is clearly both a development and an environmental issue and the FS programme developed out of discussions at a meeting of the European Regional Centres of Expertise in ESD (RCEs) in London in June 2016. There was strong agreement that the SDGs could not be achieved without addressing the question of migration and that education had a critical role to play in facilitating community well-being and integration and in harnessing the prior expertise and resources of the migrant community.

In this section, I explore the potential of MEEd as a response by educators to address some of the SDGs, focusing in particular on Goal 4: ‘Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities’ (SDG 4, 2019); Goal 8, ‘Decent work and economic growth’ (SDG 8, 2019); and Goal 16, ‘Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development’ (SDG 16, 2019). Owing to the barriers that migrants face in terms of entering the labour market or enrolling in mainstream courses, entrepreneurship education seemed to offer a route which would enable them to develop their own sense of purpose by setting up their own business. Of course, entrepreneurship does not automatically equate with sustainability goals unless it is built on foundations of sustainability values and, as previously discussed, the EU framework does not mention the need for entrepreneurship to be considered through this lens. This provides both challenges and opportunities to us as educators working within a global capitalist system which has not yet embraced the urgent need to transform itself.

Although there are differing perspectives on what constitutes pedagogy for entrepreneurship there is an increasing consensus that, as Strachan points out: ‘For many, including Gedeon (2014) and McGuigan (2016), entrepreneurship education encompasses a holistic approach to education covering not only an entrepreneurial approach to students’ jobs and careers, but also to their own lives and community. From this perspective entrepreneurial action is seen as transformational for the individual’ (Strachan, 2018: 42). In this sense, it is closely aligned with the pedagogy of ESD which focuses on active learning, problem solving, critical thinking, intercultural learning, interdisciplinarity, and lifelong learning. As Strachan (Ibid) points out: ‘The notion that education can be a transformational process ... is a key feature of ESD’. This was the pedagogical approach adopted by the FS team, embedding the ESD pedagogy within the MEEd programme.

Of course, the meaning of entrepreneurship is not the same in all countries and nor is education. Additionally, the experiences of a refugee or asylum seeker can have a deep impact both psychologically and on entrepreneurship skills and attitudes. Migrants have needs for emotional and language support, intercultural understanding, mutual learning and respect. This is not to say that there are no other vulnerable groups in society, but their needs will be different. Mainstream entrepreneurship programmes cannot address all these needs as they are planned for members of the host community and are based around participants who have ready-made social capital and local networks as well as some prior knowledge and understanding of the local business cultures and regulations. This has necessitated a tailor-made programme for migrant entrepreneurs. This is in line with Principle One in working with the SDGs: ‘Localize or domesticate an understanding of interlinkages and interconnections in the unique context of each country, region, gender and population group’ (UN Expert Group, 2018).

There are both challenges and opportunities here for educators in relation to refugees and migration. In host countries they will need to address dominant political narratives of negativity and in some cases hostility. They will need an understanding of the root causes of forced migration and be able to provide positive stories to address negative discourses. There are many opportunities to do this through, for example, challenging myths and negative stereotypes; developing intercultural understanding (ourselves, our communities, our students, fellow colleagues); promoting openness, support, welcome messages and positive induction to new migrants; opportunities for mutual learning - appreciating the skills and knowledge brought by migrants; providing opportunities for migrant and host communities to meet and get to know each other; providing opportunities for positive relationships and tools for new migrants to access the education systems and employment opportunities.

As we have found through the FS programme, the host community has a great deal to gain from developing relationships with local migrant communities and from gaining more understanding of the international and regional context of migration. The FS programme has demonstrated that where there are more opportunities to meet and socialise with different groups, there is an increase of understanding, tolerance and friendship. There are also opportunities to share new skills and expertise, as well as new languages, in addition to economic benefits in terms of employment opportunities and job creation which migrant entrepreneurs can provide. Both migrants and the host community also benefit from greater employability of migrants and contribution to taxes. Educators also have a responsibility to promote respect and appreciation for diversity and to address concepts of ‘the other’ and to challenge intolerant, racist views.

This work directly feeds into and supports the work of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO, 2014) which has highlighted how education is needed to contribute to all the proposed post-2015 goals. They will need to be competent and able to promote and teach the following:

“knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development” (SDG 4, 2019).

The principle elements and values of Education for Sustainable Development and global citizenship are clearly an essential underpinning for addressing SDG 4. Educators, whether they are in the formal, non-formal or informal sectors will need themselves to be active global citizens who espouse and practice education for sustainability.

Developing the FS programme – the three pathways

FS was a two-year EU funded programme designed to enable 120 participants (40 from each country) to develop their entrepreneurial skills and business ideas. It involved three teams from three countries - the Netherlands, the United Kingdom (UK), and Belgium and involved three universities: Zuyd University of Applied Sciences (Maastricht), London South Bank University (LSBU), and University College Leuven Limburg (UCLL) in the province of Limburg, Belgium. In London and Maastricht, the FS team recruited two cohorts and the course was delivered twice over two years. In Limburg, the course was developed through partners during the first year and then offered to one large cohort during the second year.

The FS team’s review of the terrain at the start of the project found that, although there were many common issues for migrants across the three countries, the context for each programme was different in each country and region. In the UK, it is national government which sets the rules, in the Netherlands and Belgium the local municipalities are the main authority. This underlines the importance of subsidiarity and developing pathways which are appropriate to the particular locality. A 2016 study for the European Commission showed that migrant entrepreneurship support services are often fragmented and suggested that synergies and co-operation among different service providers are needed (European Commission, 2016). Hence, while sharing the overall framework of the FS model, each country team designed a pathway which was most effective and relevant. Partners were integral to the development of this programme as they brought in added expertise, experience and contacts. In London, the key partners were a charity, Citizens UK and a social enterprise, London Small and Medium Business Centre, (known as NWES) which brought added business expertise and experience.

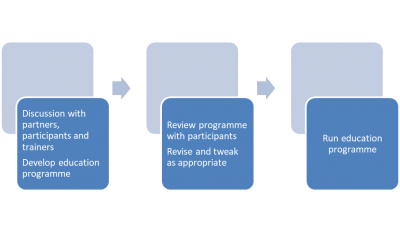

In Maastricht and London South Bank University, we built on and developed the in-house expertise within the university and its partners in entrepreneurial education and in working with refugees and migrants. Co-creation was a key principle of all pathways and both partners and participants contributed to the design of each pathway and also in evaluating them. In London and Maastricht, the participants comprised both settled and recent refugees and migrants with varying qualifications and experience, and they contributed their views in reviewing and framing the programme. In London, this took place at the launch event initially when participants were asked to review the proposed framework of the course and to help to shape it and, then again, at the end of the year. In Maastricht, this took place with participants contributing to problem identification and solving in an ongoing way throughout the course.

The UCLL pathway in Limburg differed from that of Maastricht and London because their main target group was one of highly educated, experienced, recently arrived Turkish refugees who had the confidence and skills to map their own pathways. Additionally, UCLL found that in Limburg there were already a large number of organisations providing skills training in MEEd and access to business leaders but there was very little coordination between them or awareness of what each was doing. Hence, it made sense to develop a map of support in relation to MEEd and to work with participants to choose the route most appropriate to each. Thus, strong networks were built up and links made with local banks and businesses who could offer future opportunities to migrants.

The purpose of the FS programme

The team agreed the shared purpose was as follows: to harness the prior expertise and resources of the migrant community in order to benefit the wider host community; to enhance the integration and well-being of migrants and host community; to add value to the host community and migrant community; to create positive perceptions of refugees in the destination countries; and to create connections with the entrepreneur community and the integration mediators in the destination countries The methodology used in FS was participatory action research and this enabled us to ensure that all stakeholder voices were heard and able to contribute as well as helping to create trust and mutual respect for the co-learning process. The differing target groups in each region also needed to be taken into account in order to shape the education programmes. FS started with these shared elements and principles which then followed pathways which could ‘Localize or domesticate an understanding of interlinkages and interconnections in the unique context of each country, region, gender and population group’ (UN Expert Group, 2018).

There are generally considered to be three differing approaches to entrepreneurial education:

“Teaching ‘about’ entrepreneurship means a content-laden and theoretical approach aiming to give a general understanding of the phenomenon; teaching ‘for’ entrepreneurship means an occupationally oriented approach aiming at giving budding entrepreneurs the requisite knowledge and skills. Teaching ‘through’ means a process based and often experiential approach where students go through an actual entrepreneurial learning process” (Lackeus, 2015: 10).

Through discussions with partners, trainers and participants, we developed a model with pathways which incorporated all of these elements. This model of MEEd can be contextualised for different regions and countries. However, the FS model has shared overlapping principles, aims, values, objectives and pedagogy pathways relevant to the region and context. We chose particatory action research as our methodology for the following reasons: project leaders, partners and participants themselves generate the information and then process and analyse it; the knowledge produced is used to promote actions for local change; people are the primary beneficiaries of the knowledge produced; research is a rhythm of action-reflection where knowledge produced supports local action; the knowledge is authentic since people generate it for the purpose of improving their lives.

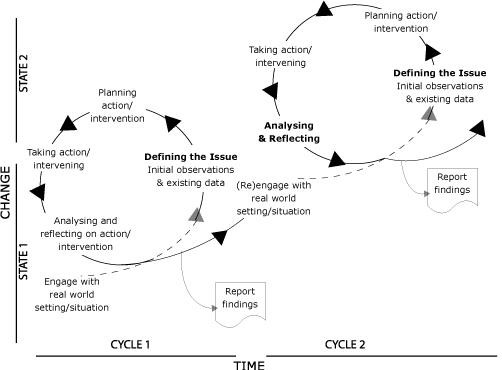

The reconnaissance stage was essential for defining the issue, exploring the local context and bringing in partners. Partners were then involved in planning, recruitment and trust building when participants also contributed to the shaping of the programme. This led on to implementation and ongoing evaluation, followed by reflection and, in year two, adapting the programme as needed.

Figure 1. PAR research for sustainable communities: post growth (Velasco, 2013).

The education programme

Using participatory action research methodology, the programme drew from all partners and from the participants in the project, with the aim of developing a co-learning environment which was appropriate and relevant to the context.

Figure 2. Developing the FS education programme.

Essential elements of the education programme incorporated ESD’s active learning pedagogy and included ongoing enquiry, reflection, co-learning based on mutual respect, shared expertise and mutual learning. The pedagogical approach was participant-centred and based on reflective, active, enquiry based, transformative learning (Mezirow, 2009; O’Sullivan, 1999). As reflective, critical learners, participants were encouraged to help to shape their own learning and give regular feedback, thus enabling participant voices to help shape the programmes according to their needs. The approach also needed to be interculturally aware and sensitive to the experience and background of participants. Access to language support was also appropriate for some participants.

Each pathway built on expertise available in their institutions and drew on regional partners. The London education programme built on expertise in the business school as well as outside knowledge and support from our partner NWES with SME experience. In London, the education programme consisted of a range of elements: the introductory launch and welcome; a series of business education workshop sessions on key areas such as the regulatory framework, access to finance, developing your business plan, knowing your customer, marketing and branding; a series of masterclasses on more specialist areas, such as digital marketing; one to ones with a business adviser with experience in setting up businesses; and group mentorship sessions which continued after the end of the programme. At the conclusion of the programme an award ceremony was held where participants could pitch their business ideas and meet with partners and migrant support organisations who could offer ongoing advice. Ongoing access to short courses at the university was also offered to participants as a means of continuing development and support where needed.

MEEd and the SDGs - illustrations from FS

Starting points - building trust and developing relationships

One of the key challenges for each FS team was to build up trust with a community which included the most vulnerable and disadvantaged, who did not necessarily feel safe or valued and yet had shown immense resilience. In London, we approached the trust building through one of our key partners, Citizens UK, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) which works as a community organiser and has strong links and relationships with local communities. Through Citizens UK we held a number of listening events in order to establish local context and needs and to ensure that voices of participants contributed to the development of the programme. Following on from this we held a launch event where we shared the plans for the programme with potential participants and stakeholders and gained their feedback which was then fed into programme development.

Evaluations from this event highlighted its importance in building trust and respect and breaking down barriers between academic and local migrant communities. Comments indicated the number of obstacles that had been faced by many in seeking employment and even just in being listened to. Employment agencies had often dismissed their experience and qualifications and funnelled them into the lowest paid jobs. Several participants said that they felt that this was the first time anyone had listened to their hopes and dreams. They all wanted urgently to contribute more to the society where they now lived and they felt that FS could support them in this, thus contributing to a feeling of inclusion and integration into a more socially sustainable society. FS thus contributed to SDG 16 (2019) which aims to ‘Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development’ as well as Goal 4 which aims to ‘Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities’ (SDG 4, 2019).

Pedagogical approaches

Our experiences in the three contexts varied according to our participant group and the programmes were designed with their needs and with the local context in mind. Some participants in all three countries were new to active transformational learning and critical thinking as their own educational experiences had mainly consisted of didactic approaches. Some participants found active learning more engaging and interesting but there were others who preferred the information giving, lecture approach more useful. The didactic approach was more relevant to key content which needed to be explained through information sharing, for example, with regard to business rules in each country. These varied considerably from many of the migrants’ countries of origin especially with regard to bureaucracy and accountability. An understanding of environmental rules and regulations was also a key element and the final business ideas of many participants illustrated their concern for, and interest in, the natural world.

The FS programme has been a transformatory learning experience for all who were involved. Trainers and mentors, reflecting on what they had learned through the programme stated that they had learned more ‘intercultural awareness, different approaches to business in different parts of the world; aspects of the participants’ cultures and more awareness of their particular skills and backgrounds’ (London South Bank University, 2019). This is in line with the requirements of ESD to draw on indigenous and local knowledge and to recognise and value different cultural contexts. It also supports learning about further key elements of ESD, by engaging ‘formal, non-formal, and informal education; (and building) civil capacity for community-based decision-making, social tolerance, environmental stewardship, adaptable workforce and quality of life’ (UNESCO, 2007).

Employability

Njaramba Whitehouse and Lee-Ross (2018), citing Poggesi Mari and De Vita (2016), highlight that there is increasing recognition of the relevance and importance of entrepreneurship for migrant women from developing countries who have settled in developed economies and aspire to become successful business owners. Most migrant entrepreneurs are male although many depend on women for unpaid support. Ogbor (2000) argues that the general concept of entrepreneurship emerges as fundamentally more masculine than feminine and this has implications for the type of courses offered. The FS programme actively recruited women and aimed to have at least equal numbers of female and male participants. Many female participants had young children and were unable to take on full-time employment, so they saw opportunities through starting up their own business. For example, one of the London participants started her own creative craft business with other mums. MEEd can thus also contribute to SDG target 4.5 which has the aim to: ‘By 2030, eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situations’ (SDG 4, 2019).

FS also provided training not merely for those who wanted to start their own business, but also offered entrepreneurial and other knowledge and skills that are valuable in paid employment. It has thus enabled participants to develop their confidence and self-esteem, and to improve language skills as well as their employability skills, through gaining an understanding of the business and enterprise culture, regulations and processes with the benefit of personal mentors and of mutual support groups. In Maastricht, for example, some started their own business, others went back to school for additional training, and one decided to first work in an enterprise to get acquainted to the Dutch way of working and Dutch construction materials before opening his own business. Our final evaluation found evidence that FS contributed to improved wellbeing and self-esteem of participants; increased self-confidence and business readiness; new startups and improved business competences and skills; and the development of new innovative ideas. MEED can therefore also contribute to SDG 8 which aims to ensure that:

“The learner is able to develop a vision and plans for their own economic life based on an analysis of their competencies and contexts. The learner understands how innovation, entrepreneurship and new job creation can contribute to decent work and a sustainability-driven economy and to the decoupling of economic growth from the impacts of natural hazards and environmental degradation. The learner is able to develop and evaluate ideas for sustainability-driven innovation and entrepreneurship. The learner is able to plan and implement entrepreneurial projects” (SDG 8, 2019)

FS courses covered legal and regulatory frameworks governing ethical and environmental issues but also facilitated and encouraged participants to embed sustainability within their business ideas. For example, London business plans included a vegan Ethiopian café, a motivation and careers consultancy to share expertise gained on the course, a business for migrants advising on book-keeping and tax returns, a handcrafted organic cosmetics business, a raw food business, and an eco-cleaning company. In Maastricht, one participant had an idea for a vegan, healthy take away (Syrian food); an online platform to match supply and demand of services for Arab speakers; and a Syrian restaurant / cultural centre which offered internships to young Syrian refugees. Many participants also wanted to build on their own experience, by sharing some of their home cultures through businesses involving food or crafts. This in turn contributed to the development of cultural appreciation and understanding. By promoting and empowering social and economic inclusion for refugees and migrants, FS has therefore contributed to SDG target 10.2: ‘By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status’ (SDG 10, 2019).

One of the London participants from Colombia credits FS with helping her to refine her business ideas and develop a business plan through to actually setting up her business; in her words ‘jumping into the actions’. She says that FS gave her an opportunity to reflect and plan with the support of her trainers and fellow participants and to finesse her brand. She already has a business partner back in Colombia and is currently in the process of developing a professional website. She is already linked into networks and contacts in Colombia and intends to build from there. The MEEd programme can also support SDG targets 4.4 and 4.3:

“By 2030, substantially increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship” (SDG 4, 2019).

“By 2030, ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university” (Ibid).

We have seen that refugees and migrants have a great deal of experience and expertise to offer and are keen to contribute to the wider community and they present a valuable resource for the community. In order to maximise this potential, FS identified a number of practical obstacles which policymakers need to address in order to facilitate such programmes. For example, the lack of a cohesive policy for English as an additional language in London meant that language classes are difficult to find at appropriate times, thus holding back language development of new migrants. Additionally, the benefit system required migrants to be available for work during the daytime, thus meaning that classes had to be held in the evening which in turn impinged on childcare needs. This meant that sometimes participants could not get to classes or arrived late.

Building inclusion and integration through mentoring and networking

Strong relationships were built before starting the course and a high level of trust was engendered as a result of this. In London, Citizens UK, also provided ongoing support and encouragement throughout the course and ensured that participants were linked into local social networks. Community engagement was achieved through networking and events in the community, such as the launch events, award ceremonies, meetings with policymakers. In the London context of a very mobile and multicultural society, community engagement is more straightforward, but it can be more of a challenge where there is quite a mono-cultural host community, such as Limburg. More emphasis and time could be allotted to promoting community engagement if funding were to be available for future, more extended courses which would benefit both migrants and the host communities.

In London, NWES offered ongoing access to on-line business courses and LSBU has provided access to enterprise initiatives. At the award ceremony, we invited local business organisations and refugee support groups to attend so that participants could network with them and build on their social networks. A celebratory event took place at the completion of the course where participants were invited to pitch their business ideas and were awarded certificates. This was a very important part of the programme in acknowledging their achievements as well as giving them outside validation and endorsement. Ongoing support in the form of business mentors was made available as well as access to on-line courses in business tools. One of the most important results of the programme was the support networks which participants developed themselves. Through a WhatsApp group, they kept in touch, shared ideas and actively supported each other’s business ventures. Participants also acknowledged and built on their own links to advice networks in the home and host countries which also demonstrates the importance of contacts outside the ethnic community, and of advice and expertise from the home country.

Conclusion – taking it forward

Sustainable development is about living peacefully within planetary boundaries in consideration and respect for the natural world and for the needs of future generations. Social justice plays an integral part in this and courses like FS can contribute to the delivery of the SDGs by addressing issues of ‘sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity’ (SDG 4, 2019). At the end of the programme, participants in London were asked to share their views on barriers and opportunities for developing their business ideas and employability skills and to develop some suggestions and advice for policy makers. These were shared with refugee groups and policy makers (local councillors and MPs) at a symposium in the House of Commons in June 2019. Key points included the following: ‘the need for more language support; more accessible child care; more flexibility in the benefit system; robust and fully funded FS type courses; mentorships with local businesses; mechanisms to provide targeted micro finance’ (comments from participant discussion, June 2019).

The SDGs cannot be achieved without attention being given to the challenges of forced migration, both the causes and the effects. In this article, I have outlined the potential of MEEd to provide some ways forward. The experience of designing and developing the FS programme has produced a replicable, flexible model which can be adapted for migrant entrepreneurship courses in any region. We have learned a lot from this process which has provided benefits to participants, trainers, stakeholders, and members of the host community. The FS model has the potential to add value through enhanced well-being, employability, business skills, integration, social cohesion and thus can contribute to the development of more sustainable communities and the achievement of the SDGs.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to extend my thanks to all the FS team, partners and participants for their contributions to the development of the programme and their reflections on ideas expressed in this article.

References

Ashourizadeh, S, Schøtt, T, Şengüler, E P and Wang, Y (2016) ‘Exporting by migrants and indigenous entrepreneurs: contingent on gender and education’, International Journal of Business and Globalisation, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp.264–283.

Binney, C and Williams, G (1997) Leaning into the Future: Changing the Way People Change Institutions, London: Nicholas Brearley publishing.

Bowe, R, Ball, S and Gold, A (1992) Reforming Education and Changing Schools: Case studies in Policy Sociology, London: Routledge.

Brown, O (2008) Migration and Climate Change, Geneva: International Organisation for Migration (IOM).

Elliot, L (2019) ‘Global warming could create 'greater migratory pressure from Africa’, The Guardian, 11 April, available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/apr/11/expect-even-greater-migration-from-africa-says-attenborough-imf-global-warming (accessed 12 March 2020).

European Commission (2016) Evaluation and Analysis of Good Practices in Promoting and Supporting Migrant Entrepreneurship, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, available: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/e4c566f2-6cfc-11e7-b2f2-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed 19 March 2020).

European Commission (2020) Public consultation on the Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan, available: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/promoting-entrepreneurship/action-plan_en (accessed 12 March 2020).

European Union (2016) Entrepreneurship Competence Framework (Entrecomp), available: http://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC101581/lfna27939enn.pd (accessed 18 February 2020).

Gedeon, S (2014) ‘Application of Best Practices in University Entrepreneurship Education’, European Journal of Training and Development, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 231-253.

Gleick, P (2014) ‘Water, Drought, Climate Change, and Conflict in Syria’, AMS Journal, 1 July, available: https://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/10.1175/WCAS-D-13-00059.1 (accessed 18 February 2020).

Lackeus, M (2015) Entrepreneurship Education: What? Why? When? How ?, Entrepreneurship Background Paper, Paris: OECD, available: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/BGP_Entrepreneurship-in-Education.pdf (accessed 10 March 2020).

London South Bank University (2019) ‘Fresh Start trainers’ and mentors’ evaluations’, (unpublished).

McGuigan, P (2016) ‘Practicing what we preach: Entrepreneurship in entrepreneurship Education’, Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 38-50.

Mezirow, J (2009) ‘Transformative learning theory’, in J Mezirow, and E W Taylor (eds.) Transformative Learning in Practise: Insights from Community, Workplace, and Higher Education, San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass

Njaramba, J, Whitehouse, H and Lee-Ross, D (2018) ‘Approach towards female African migrant entrepreneurship research’, Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Center, 2018, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp.1043 – 1053.

Ogbor, J O (2000) ‘Mythicizing and Reification in Entrepreneurial Discourse: Ideology Critique of Entrepreneurial Studies’, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 37, No. 5, 605-635.

O’Sullivan, E (1999) Transformative Learning: Educational Vision for the 21st Century, London: Zed books.

Poggesi, S, Mari M and De Vita L (2016) ‘What’s new in female entrepreneurship research? Answers from the literature’, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, DOI 10.1007/s11365-015-0364-5

Sustainable Development Goal 2 (SDG 2) (2019) ‘Sustainable Development Goal 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture’, available: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg2 (accessed 30 March 2020).

Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) (2019) ‘Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’, available: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg4 (accessed 30 March 2020).

Sustainable Development Goal 8 (SDG 8) (2019) ‘Sustainable Development Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all’, available: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg8 (accessed 30 March 2020).

Sustainable Development Goal 10 (SDG 10) (2019) ‘Sustainable Development Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries’, available: (2020) available https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg10 (accessed 30 March 2020).

Sustainable Development Goal 12 (SDG 12) (2019) ‘Sustainable Development Goal 12: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns’, available https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg12 (accessed 30 March 2020).

Sustainable Development Goal 13 (SDG 13) (2019) ‘Sustainable Development Goal 13:Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts’, available: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg13 (accessed 30 March 2020).

Sustainable Development Goal 16 (SDG 16) (2019) ‘Sustainable Development Goal 16: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels’, available: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg16 (accessed 30 March 2020).

Sustainable Development Goal 17 (SDG 17) (2019) ‘Sustainable Development Goal 17: Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development’, available: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg17 (accessed 30 March 2020).

Strachan, G (2018) ‘Can Education for Sustainable Development Change Entrepreneurship Education to Deliver a Sustainable Future?’, Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education. Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 36-49.

United Nations (UN) (1992) ‘United Nations Conference on Environment and Development; Earth Summit’, available: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/milestones/unced (accessed 12th March 2020).

United Nations (UN) (2020) The Sustainable Development Goals, available: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/ (accessed 29 March 2020).

United Nations Environnent Programme (UNEP) (2019c) Global Environnemental Outlook, available: https://www.unenvironment.org/resources/global-environment-outlook-6 (accessed 18 February 2020).

United Nation (EU) Expert Group (2018) Advancing the 2030 Agenda: Interlinkages and Common Themes at the HLPF 2018: Report of the meeting, 25-26 January 2018, New York: United Nations.

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) (2019) ‘Figures at a Glance’, available: https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html (accessed 12 December 2019).

UNESCO (2007) ‘Introductory note on ESD-DESD Monitoring and Evaluation Framework’, Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2014) Sustainable development begins with education: how education can contribute to the post 2015 goals, Paris: UNESCO, available: https://en.unesco.org/news/unesco-sustainable-development-begins-education (accessed 10 March 2020).

Velasco, X C (2013) Participatory Action Research for Sustainable Community Development, 20 August, available: http://postgrowth.org/participatory-action-research-par-for-sustainable-community-development/ (accessed 20 March 2020).

Ros Wade founded the Sustainability Research Group at London South Bank University (part of the Centre for Social Justice and Global Responsibility) where she also chairs the London Regional Centre for Education for Sustainability (RCE). She is a distinguished research fellow of the Schumacher Institute for Sustainable Solutions. She was a lead researcher in the EU funded FS project on migrant entrepreneurial education from 2017-2019. Her publications include (with Hugh Atkinson) The Challenge of Sustainability: Linking, Learning, Polities and Education (London: Policy Press). E-mail: rostwade@gmail.com.