Addressing ‘Root Causes’? Development Agencies, Development Education and Global Economics

Development Education and the Economic Paradigm

Abstract: How much attention to the global economic system do the international development and development education sectors give? Based on a small scale research assignment concerned with the situation in Ireland (but including references to elsewhere in Europe) the answer has to be: not much. Although within both sectors evidence exists of attention to economic systems and their impact on poverty, inequality and injustice, most development agencies referred to in the article do not contextualise their work in a broader, explanatory framework. Aside from that, both sectors appear to give little attention to engaging the public in educational processes that attempt to explore, discuss, reflect on and respond to such structural economic issues.

The article outlines the findings from the research, based on the premise that for the sectors to be successful in creating a lasting impact on poverty, inequality and injustice they need to give attention to the root causes of those issues, and that this will require attention to systemic economic processes and ideologies and to the development of educational approaches involving the public with those issues, processes and ideologies. Conceptually, the article discusses global economic processes as an expression of neoliberalism / ‘free market’ economics. In investigating how those processes operate according to development agency policy analyses the research referred to Systems Thinking as a means of investigating and clarifying global development phenomena, making use of an adaptation of the Development Compass Rose to highlight the interlinked and dynamic nature of global economics. Without coming to firm conclusions, but hoping that it will lead to further work on this, the article also addresses the question of what helps or hinders the sectors from giving attention to global economic systems in their education work with the public.

Key words: Development; Education; Neoliberalism/Free Market Economics; Systems Thinking; Local-Global.

Exploring and addressing ‘root causes’ of poverty, inequality and injustice

The research that led to this article involved a small scale assignment relating to the Irish international development (ID) and development education (DE) sectors. It focussed, firstly, on the attention given by the ID and DE sectors to global economic processes and their influence on poverty, inequality and injustice. Secondly, the research aimed to get a sense of how that attention was used by organisations in educational efforts that enable enquiry, discussion, reflection and responses to the reasons for the existence of poverty, inequality and injustice. The intention was to obtain an indicative analysis of the situation which, it is hoped, will lead to further work and discussions by ID and DE organisations in furthering education work that engages the public with the system of global economics and with explorations of potential responses.

Underpinning the research were two assumptions, namely that:

- for their work to have lasting impact, international development and development education efforts need to give attention to ‘root causes’ of poverty, inequality and injustice and involve the public in investigations of and responses to those causes;

- and that to do so requires attention to structural-systemic (economic) processes and ideologies.

Investigations included a review of webpages produced by a selection of nine Irish Non-Governmental Development Organisations (NGDOs), the NGDO networks Dóchas and CONCORD, the Irish Development Education Association (IDEA), Irish Aid and the European Union / Commission. This involved a study of their introductory pages to establish what the agencies’ main concerns were, of relevant policy documents produced by the agencies, and of the attention given by them through formal and non-formal education work that enquires into and enables responses to such issues and analyses.

The ID sector was seen as being primarily concerned with efforts to advance the amelioration and eradication of poverty, promoting sustainable development, and advancing human rights (ID Web, 2022). The research viewed DE as primarily concerned with educational processes that ‘… enable people to participate in the development of their community, their nation and the world as a whole …’ (Ishii, 2003: 9, quoting FAO-JUNIC, 1975), enabling investigations into, discussions of, reflections on and responses to issues and processes (DE Web, 2022; Freire, 1970; Hope and Timmel, 1984; Bourn, 2015). The nine Irish NGDOs were selected mainly because of their established nature within the Irish ID sector, i.c. ActionAid, Children in Crossfire, Christian Aid, Concern Worldwide, Oxfam, Plan International, Trócaire, UNICEF and World Vision.

The reviews of webpages and agency policy analyses was added to by reference to literature concerning the growth and development of the current global economic system. In addition, a questionnaire was circulated to some two hundred ID and DE sector practitioners and two seminars were organised gathering responses to the research findings. Both questionnaire and seminars involved respondents from the island of Ireland as well as from other parts of Europe. The questionnaire, which obtained twenty-nine responses, asked about the priorities of the agencies in which respondents were involved and about respondents’ opinions relating to the issues of the research. The seminars, involving twenty-two participants, focussed on the challenges and opportunities that ID and DE organisations have in addressing global economics through education. Neither the questionnaire responses nor the seminar conclusions can be seen as representative of the range of experiences and opinions in either sector, however findings from both sources do provide perspectives that are worth further investigation if the sectors are concerned with addressing root causes of poverty, inequality and injustice.

Although the research had a particular focus on findings from the island of Ireland it is likely, also given responses from questionnaire and seminar participants, that findings in contexts elsewhere in Europe will not be significantly different.

A systems approach

Understanding and impactful responding to issues of poverty, inequality and injustice requires an ability to place specific, seemingly unique cases and experiences in a broader context. This involves the ability to conceptualise and systematise: viewing the whole as more than the sum of individual, single development phenomena, and viewing that whole as a dynamic, interconnected web that affects how development issues are perceived or can be responded to (Hanvey, 1976; Pike and Selby, 1988: 27-29; Anderson and Johnson, 1997; Ramalingam, 2013: 141-142; Green, 2016; Veltmeyer and Bowles, 2022). Questionnaire and seminar respondents were in agreement with the intention that within an education context attention to creating ‘… comprehension of key traits and mechanisms of the world system, with emphasis on theories and concepts …’ (Hanvey, 1976: 19) is an important tool of enquiry as well as a prompt for discussion about, a means to reflect on, and a stimulus for creating responses.

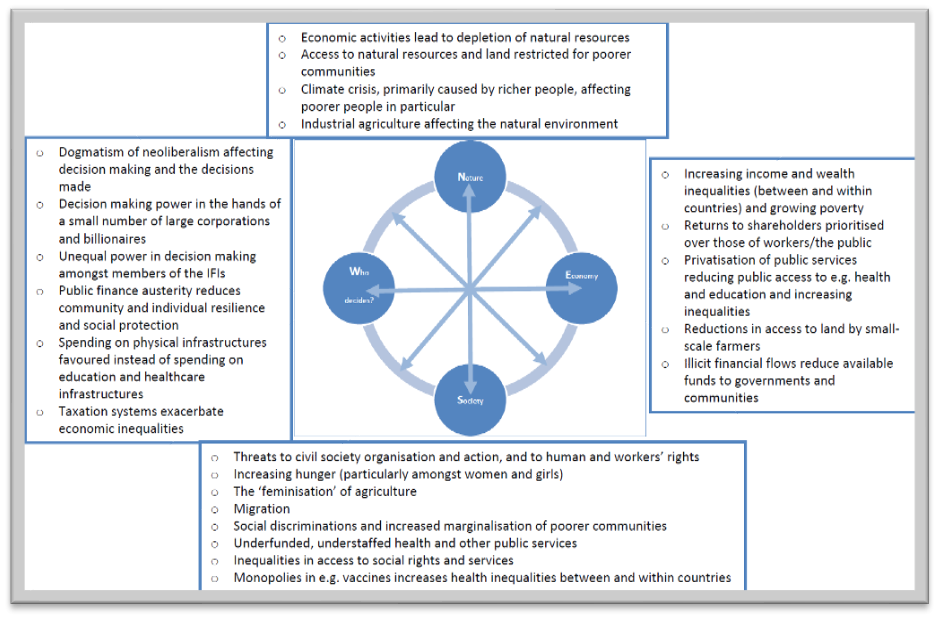

One way of categorising and systematising experiences of poverty, inequality and injustice (such as those highlighted by the ID and DE sectors) is through the use of a Development Compass Rose (Tide, 1995). In this, the usual cardinal points of North, South, East and West are replaced by Nature, Society, Economy and Who Decides? (i.e. politics). The resulting ‘compass’ enables investigation of a locality, of an issue, or of a process: raising questions or identifying features that relate to, for instance, social organisation and culture (S), production and trade (E), decision making and power (W), or the natural environment (N). In between the four cardinal points relationships can be explored, such as the impact of economic activity on the natural environment (NE), the decision making process and powers that enable or prevent protection of the natural environment (NW), the way in which people are organising themselves to create change (SW), or the accessibility or not of economic activity to particular groups in society (SW). Similar relationships can be highlighted between Economics and Who Decides?, for example about decisions to do with the division of benefits of economic activity (‘who gets what and how much?’), or between Society and Nature, for instance regarding the attitudes that people have towards the natural environment. It is through identification of those relationships that the dynamic influence of, for instance, an economic philosophy and practice on the rest of life can be explored.

The concerns of sampled agencies

A review of ‘What we do’, ‘About us’ and similar webpages of selected ID sector agencies in Ireland (ID Web, 2022) highlights the sector’s concern for sustainable development (e.g. Irish Aid), addressing inequality (for instance, ActionAid, Irish Aid), and ending poverty (Trócaire and Oxfam amongst others). For many NGDOs in Ireland those concerns are particularly related to work with children (e.g. Children in Crossfire, Plan International, World Vision). Some agencies in their introductory webpages make explicit reference to structural issues they wish to address (for instance in relation to women (ActionAid), economic inequalities (Christian Aid) or food systems (Oxfam)), but most do not place their work in such a systemic context – at least not in these webpages.

In their introductions, the nine sampled NGDOs refer to work involving the public in Ireland mainly in the context of fundraising, although references to ‘awareness raising’, ‘advocacy’ and ‘campaigning’ are also made by the majority of organisations. Reference to ‘education’ is rare and where this is made at all it, with the exception of Children in Crossfire, refers to work ‘overseas’ and not in Ireland.

Looking at similar ‘What we do’ pages concerning development education (DE Web, 2022) key words that are highlighted relate to education, global citizenship (e.g. Irish Aid, IDEA), lifelong learning (Irish Aid, a.o.), awareness (e.g. Dóchas), and empowerment (e.g. IDEA) - all in respect of issues of, amongst others, climate change, inequality, poverty, sustainability. Irish Aid, IDEA and the Dóchas Development Education Working Group all make reference to the ‘Code of Good Practice for Development Education’ (IDEA, n.d.) which lists twelve core principles relating to both educational and organisational practices that are seen as core to the provision of good quality DE. However, it is noticeable that, for example, ActionAid, Oxfam and World Vision appear to be neither members of the Dóchas DE Working Group (which involves 17 of the network’s 57 members), nor of the DE network of IDEA (with some 63 organisational members).

Analyses of development

Although most of the selected ID agencies publish case studies of the work they carry out or support, most do not appear to publish policy analyses of the issues that are of their concern, or if they do then they do not make them easily accessible through their sites. Policy making bodies, such as Irish Aid and the European Union will state their strategies (Irish Aid, n.d.; European Union, 2017; European Commission, 2019), but tend not to provide an analysis of the reasons for the existence of the issues they aim to address.

Reviewed reports by those ID sector agencies that do provide a more thorough analysis focus on: an analysis of reasons for increasing food insecurity and malnutrition (Trócaire, 2018), the structural reasons for the existence of inequalities (CONCORD, 2019), the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic given the current economic system (Dóchas, 2020), an analysis of IMF (International Monetary Fund) policies that promote or lead to public austerity measures (ActionAid et al, 2021), and the symptoms of and reasons for widening economic, gender and racial inequalities (Oxfam, 2022).

Although focussed on different areas of development, when viewed together, the reports suggest that there is a clear and direct relationship between economic structural causes and its effects not only on economic well-being, but also on social organisation, natural-environmental conditions and on decision-making. The illustration below presents some of the issues identified in the reports in the shape of a Development Compass Rose (adapted from Tide, 1995).

The growth of a globally dominant economic philosophy, ideology and practice

The NGDO reports mentioned above all refer to a structure and system that underpins, causes or exacerbates the development phenomena that the agencies experience through their work. Giving that system a name, such as ‘neoliberalism’ (ActionAid et al., 2021: 5), is often avoided. The reasons for that lack of conceptualisation may be multivarious: amongst economists the term ‘neoliberalism’ is regularly avoided since its interpretations are considered imprecise, contested, or pejorative (with some preferring to use ‘free market economics’ instead), while for others policies described as neoliberal are disowned as such by their authors (Williamson, 2002; Eagleton-Pierce, 2016; Rowden, 2016; Harvey, 2019; Babb and Kentikelenis, 2021).

Despite confusion and disagreement about interpretations of the term (a type of confusion that should be well familiar amongst those involved in development education and other forms of adjectival educations), for questionnaire respondents and seminar participants conceptualising the global economic system by use of a term such as ‘neoliberalism’ is useful (although most are also of the opinion that use of such a term when communicating with the public may not be helpful). At the risk of over-simplification and while ignoring many of its various forms (such as those sketched out by Dobre [2019] when discussing interpretations of the concept in European policies), what are (some of) the core characteristics of ‘the doctrine sometimes called neo-liberalism’ (Friedman, 1951)?

For the past 40 or 50 years the world’s economic, social, political and environmental affairs have increasingly become geared towards an approach that values individual, or rather private business, initiative in industry and commerce. This involves a leading role for markets in allocating investments, combined with a role for the state that is focussed on enabling such private initiatives to flourish through competition and on creating a policy environment for largely unrestricted trade across international borders. This is more often than not combined with a deliberate reduction in the role collective action by civil society in influencing, steering or determining economic affairs (at least when compared with previous decades) (Clarke, 2005; Eagleton-Pierce, 2016; Harvey, 2019; Babb and Kentikelenis, 2021). The philosophy underpinning this development was initially offered as a response to what was seen as undue influence of the state on directing economic activities: the role of ‘free’ markets was believed to be (economically) more efficient and effective in creating economic growth and welfare (Eagleton-Pierce, 2016: 118-125; Goldin, 2016: 29-34).

In the post-Second World War period of reconstruction and in the initial post-colonial period of the 1950s and 1960s, state governments played a significant role in directing and supporting economic and social development: re-building or building societies through national planning of investments, preferential treatment for certain types of economic and social activity through laws, tax regimes and subsidies, and greater or lesser forms of protection of the national economy against competition from abroad (Goldin, 2016: 18-36; Polanyi Levitt, 2022). It was against that ‘faith in collectivism’ as a driver of economic growth and social welfare, and hence against the role of the state in directing the development of the economy, that economist Milton Friedman proposed in 1951:

“a new faith […that…] must give high place to a severe limitation of the power of the state to interfere in the detailed activities of individuals; at the same time, it must explicitly recognize that there are important positive functions that must be performed by the state [in particular in respect of]:

- [ensuring] conditions favorable to competition […]

- [preventing] monopoly […]

- [providing] a stable monetary framework […]

- [relieving] acute misery and distress” (Friedman, 1951: 3-4).

That neoliberal faith became a mainstay of economics teaching in many of the world’s higher education institutions, influencing policy makers across the globe and through them the policies that have been made (Babb and Kentikelenis, 2021: 8-9; ActionAid et al., 2021: 7, 16). Although various forms of neoliberalism exist (in the case of Europe see, for instance, Dobre, 2019) in broad terms its practical development and spread can be characterised as having gone through a number of stages (Leeson, 1988; Williamson, 1990; Dorn, 1997; Williamson, 2002; Eagleton-Pierce, 2016; Goldin, 2016; Rowden, 2016; Harvey, 2019; Harriss, 2019; Babb and Kentikelenis, 2021; Polanyi Levitt, 2022).

Amongst the ‘early adopters’ three countries stand out: Chile, under the dictatorship of Pinochet following a military coup against the government of Salvador Allende in 1973, the United Kingdom (UK) after 1979, during the government of Margaret Thatcher, and the United States (US) after 1981, during the Presidency of Ronald Reagan. This led, amongst other policies, to various forms of privatisation of public and state enterprises, restrictions on the organisation and influence of labour and other collective associations, and trade liberalisation.

A second phase in the implementation of Friedman’s ‘new faith’ was entered in response to the late-1970s and 1980s debt crisis in which many developing countries found themselves. It led to an expansion of the range of countries that implemented core policies of free market economics. To relieve their indebtedness, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other financial institutions offered support to affected countries. In return for such support indebted countries were obliged to introduce ‘structural adjustment programmes’ which drew upon many of the policies introduced in Chile, the UK and the US, involving abolishment of state support for, amongst others, import-substituting enterprises and ending the state’s direction of agricultural development (Eagleton-Pierce, 2016: 40-46). The lead for agricultural and industrial development was switched from the state to private enterprise – with the state focussing on introducing those regulations that were seen as a proper role for the state (see above regarding Friedman’s suggestions), combined with an emphasis on enabling a largely unfettered access to investments from and trade with companies from other countries.

A third phase in the development of neoliberal practice, making it the truly globally dominant form of economic practice, followed the collapse of the Soviet empire (in the early 1990s) and, particularly, the opening up of China to trade with the rest of the world (since the late 1990s). That phase is characterised by increased globalisation of economic activity, exemplified by ‘global value chains’ involving ‘developing’ and ‘developed’ countries alike in a production and trade process that is based on multiple transactions between multiple locations before a final product is provided to an ultimate user (World Bank, 2020: 19). This stage of neoliberalism has also been accompanied by further restrictions in public spending, for example on welfare programmes, particularly following the financial, banking crises of 2008-09; public spending restrictions that were additional to those already implemented during the second phase (their effects are explored in many of the reviewed NGDO reports).

The intentions of neoliberal policies as initially advocated by Friedman, for instance regarding economic growth and relief of ‘acute misery and distress’, have not always been fulfilled. For example, structural adjustment programmes often resulted in economic decline rather than growth (Goldin, 2016: 34). Reductions in the state’s involvement in economic affairs typically led to increased unemployment, rising costs of living and growing poverty accompanied by hunger, and where growth did occur, any benefits tended to accrue to a small segment of society – in both ‘developing’ and ‘developed’ countries (Eagleton-Pierce, 2016: 43-44, ActionAid et al, 2021, Oxfam, 2022). Although income inequalities between countries have significantly gone down since 1980 (around the start of phase two as outlined above), income inequalities within countries have seen a sharp rise, with global income inequalities within and between countries in 2020 being comparable to the situation in 1880-1890 (Chancel et al., 2021: 56-58). Although global and individual ‘wealth’ (ownership of financial assets, such as equity and bonds, and non-financial assets, such as buildings and land) and of its growth are difficult to calculate, the World Inequality Lab (2022) comes to the conclusion that wealth inequalities have risen sharply between 1995 and 2021. Of a total growth in wealth per adult of 3.2 per cent during that period, the top one per cent captured thirty-eight per cent of this growth, against a bottom fifty per cent capturing only two per cent (Chancel et al., 2021: 90-91).

The policy response to the negative effects of neoliberal policies has been a somewhat greater recognition of the need for the state to influence investment in social and physical infrastructures, typically involving the development of ‘public private partnerships’. Design of the Millennium Development Goals, in 2000, and particularly of the Sustainable Development Goals, in 2015, can also be seen as a recognition of the need to address some of inequities caused by the current economic system – however, without fundamentally addressing its core features (Eagleton-Pierce, 2016: 44-45; Goldin, 2016: 34-36; Van Wayenberge, 2022: 119).

Comparing the various characteristics of neoliberalism outlined above with the experiences of the ID sector as analysed by their reports and as illustrated through the Development Compass Rose, highlights the dynamic, mutually reinforcing relationships between the ‘doctrine sometimes called neo-liberalism’ (Friedman, 1951), its implementation in economic affairs and its effects on society and social justice, on decision making and power, and on the natural environment.

The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, referred to in both the Dóchas (2020) and the Oxfam (2022) papers, and the effects of the current war in Ukraine – leading to interrupted international trade flows, increasing inflation, and growing costs of living - question some of the foundations of the third phase of neoliberalism as sketched out above, not least the reliance of (business and national) economies on global value chains. Responses to these consequences may lead to a retrenchment into core neoliberal policies of the ideology, or to a further adjustment of neoliberalism, or to a transformation of the doctrine into something different. The analyses by Dóchas, ActionAid, CONCORD, Oxfam and Trócaire all offer starting points for further exploration of options to address the issues highlighted by the reports. Such an exploration potentially offers opportunities too for involving the (Irish) public in an education process that investigates, discusses, reflects and responds to the global and local relevance of the issues: building the agencies’ constituencies in support of their stated intentions. Unfortunately, it seems that the agencies, with the possible exception of Trócaire, do not make use of that opportunity; the absence of a dedicated education programme means that most don’t even have that ability.

Global economics and development education

Most of the sampled NGDOs have not developed and published analyses that place (aspects of) their work in a broader structural context and most, including the minority that does carry out such analyses, do not give attention, or seem to have the intention, to involve the public in educational processes that explore the systems that underpin, cause or exacerbate the issues that are of the agencies’ concern. The main activities involving the domestic public which the agencies employ – fundraising, awareness raising, campaigning – appear based on the creation of ‘global awareness’: eliciting a response from the public that is based on the public’s existing empathy or compassion based on their existing understanding of the world and their existing disposition towards action (Lissner, 1977: 138-45; Lattimer, 1994: 329-336; Kingham and Coe, 2005: 84-88; Darnton and Kirk, 2011; Green, 2016: 179-195). Opportunities to explore and develop additional or new perceptions of global realities, including its systemic nature, appears largely absent. However, without attention to the systemic nature of the causes of poverty, inequality and injustice it is likely that agencies will contribute little to a sustained transformation of the existing realities of poverty, inequality and injustice – although such a transformation is what many of the selected agencies seem to be looking for:

- ‘working to end poverty and inequality’ (ActionAid)

- ‘committed to ending poverty worldwide’ (Christian Aid)

- ‘[striving] for a world free from poverty, fear and oppression’ (Concern Worldwide)

- ‘to bring about lasting solutions to the problems of global poverty and inequality’ (Dóchas)

- ‘empower learners of all ages to become active global citizens’ (IDEA)

- ‘[mobilising] the power of people against poverty’ (Oxfam)

- ‘life-changing support for some of the world’s poorest people’ (Trócaire)

(DE Web, 2022; ID Web, 2022).

For such a sustained transformation to happen awareness needs to include a recognition of the local conditions ‘there’ and ‘here’ as part of a globally interrelated system. For that to be successful would require a recognition and questioning of existing empathies, compassions, understandings and dispositions: a process of transformative learning or ‘conscientisation’ involving, for example, investigations, discussions and reflections on current realities and options, and drawing conclusions on the basis of that learning that leads to personal and communal responses (Lissner, 1977: 138-145; Fricke et al, 2015: 14-23 and 45-51; Bourn, 2022: 121-138; Freire, 1970; Hope and Timmel, 1984).

Arguably, quality DE would provide the opportunity for such a process, but practically DE does not seem to do this often. Information about European Union (EU DEAR, n.d.) supported Development Education and Awareness Raising (DEAR) projects in Ireland indicates that, although quite a few projects relate to issues of poverty, only some appear to have placed their discussions and work in a broader systemic or economic context. Similarly, a review of DE publications produced in Ireland in the period 2013 to 2016 (Daly et al., 2017) seems to indicate that few of these resources relate to a global framework or to a pedagogy that explores the structures underpinning the issues that the resources deal with, leading the authors of the review to comment that ‘Many resources […] present simplistic analyses of issues …’ or, in the contexts of the SDGs, are ‘simply PR focussed rather than educationally analytical’ (Daly et al, 2017: 32 and 39). Participants in the seminars also referred to this, for example by mentioning that the current, often uncritical, focus on the SDGs typically involved awareness of issues that are ‘a mile wide, but only an inch deep’.

Challenges and Opportunities

Questionnaire respondents and seminar participants were of the opinion that both the ID and the DE sectors are not doing enough to explore the economic causes of poverty, inequality and injustice and that systems thinking is an important means by which to explore such causes. Assuming that ID and DE organisations are serious about wanting to address root causes, ‘global awareness’ as described above will not be adequate in doing that and different approaches will be needed.

Enquiry based education approaches potentially can assist – and are likely necessary – in creating the sustained transformations (globally and locally) envisaged by many (most?) in both the ID and the DE Sectors. They also offer opportunities to more closely engage members of the public with the challenges faced by the sectors: rather than consumers of agency designed products (be it ‘consumption’ of a fundraising ask, a campaigning action, or an awareness raising activity), enquiry based education offers learners, including the facilitating organisations, to become producers of new understandings and (collective) responses to the issues they face.

Which is not to say that there are no challenges to overcome in doing that. Seminar participants started to identify such challenges of which some are mentioned below. Although this listing is far from complete it may offer a starting point for discussion by ID and DE organisations on what needs to be done to address current hiatuses in the sectors – if the sectors are to contribute to sustained transformations that address root causes of poverty, inequality and injustice.

Some of the challenges may be based on fear: a fear that giving attention to the ‘domestic’ relevance and experiences of ‘overseas’ development issues will be controversial and as a result it will negatively affect the domestic fundraising of organisations, be it to do with income from individuals or with that from the state. The will of agencies to act on stated intentions through involvement of the domestic public in explorations of contentious issues may, therefore, be weak.

For the past 40 forty or so years neoliberalism, as characterised in this article, has played a central role in our economic affairs – and from that has influenced our politics, our way of living and of relating to each other, and, arguably, our natural environment. The precedence given to individual enterprise has probably affected all our thinking and behaviour (Taylor-Gooby and Leruth, 2018): giving priority to individual, single issue considerations and actions rather than systemic, holistic explanations and collective actions. One of the seminar participants mentioned in this context the sectors’ ‘focus on individualism e.g. carbon footprints [which has meant a] lack of tools for collective measures’.

A further challenge relates to terminologies. As mentioned previously, conceptualising the global economic system under the banner of ‘neoliberalism’ can be problematic. Not only since the term, for instance in public discourse, ‘has now become a kind of catch-all expression or “explanatory catholicon”’ (Eagleton-Pierce, 2016: xiii), but also because of the complexity which is hidden by such a concept. Rather than clarifying, its use can be obfuscating. Making the complexity of concepts, systemic relationships and their implications understandable in plain language is a challenge: terminologies can be a ‘turn-off’. Exploring the complexities of the global economic system and its impact can also be daunting, particularly where organisations and educators, amongst others, lack confidence.

Opportunities to address such challenges do, however, exist. Irish Aid, in its latest relevant strategy, includes reference to the ‘Code of Good Practice for DE’ (Irish Aid, n.d.: 5), enabling funding requests for activities that explore root causes through education. The European Commission’s latest objectives for the DEAR grants programme refer to ‘empowered EU citizens’ and ‘addressing global challenges (notably global inequalities and ecological crises)’ (European Commission, 2021: 14-15) which build on aspects of the EU’s development strategy and its attention to an ‘enabling space for civil society’ addressing ‘root causes’ of ‘poverty, conflict, fragility and forced displacement’ (European Union, 2017: 33).

Good quality DE provides a way to address issues of complexity and confidence. Whilst not shying away from contentious issues (are there any that are not contentious when discussing ‘development’?) quality DE offers an educational process:

“by which people, through personal experience and shared knowledge:

- Gain experience of, develop and practice dispositions and values which are critical to a just and democratic society and a sustainable world;

- Engage with, develop and apply ideas and understandings which help explain the origins, diversity and dynamic nature of society, including the interactions between and among societies, cultures, individuals and environments;

- Engage with, develop and practice capabilities and skills which enable investigation of society, discussion of issues, problem-tackling, decision-making, and working co-operatively with others;

- Take actions that are inspired by these ideas, values and skills and which contribute to the achievement of a more just and caring world”

- (Regan and Sinclair, 2002: 50).

Such an approach would offer an opportunity to address obstacles and challenges mentioned above: both the current economic situation, with its growing inequalities in Ireland, Europe and globally, and the approaches of development education, with its use of participatory learning, offer ample opportunities for ID and DE sectors and organisations to enable people to participate in development.

The research on which this article is based had a limited scope and more attention to the issues raised by it would be worthwhile. Investigations and discussions could, for example usefully address the question of how the practices of organisations, that are currently often focussed on ‘single’ issues, can incorporate the facilitation of global systems thinking in their work, in particular through education approaches that actively include people in a process that enquires into, discusses, reflects on and responds to the dominant global economic system.

References

ActionAid, Public Services International, and Education International (2021) The Public versus Austerity – why public sector wage bill constraints must end, available: https://actionaid.org/publications/2021/public-versus-austerity-why-public-sector-wage-bill-constraints-must-end (accessed 28 February 2022).

Anderson, V, and Johnson, L (1997) Systems Thinking Basics: From Concepts to Causal Loops, Westford (MA): Pegasus.

Babb, S and Kentikelenis, A (2021) ‘Markets Everywhere - the Washington Consensus and the sociology of global institutional change’, in Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 47, 521-541, available: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-soc-090220-025543 (accessed 28 February 2022).

Bourn, D (2015) The Theory and Practice of Development Education: A pedagogy for global social justice, London and New York: Routledge.

Bourn, D (2022) Education for Social Change: Perspectives on Global Learning, London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Chancel, L, Piketty, T, Saez, E, Zucman G et al (2021) ‘World Inequality Report 2022’, World Inequality Lab, available: https://wid.world/news-article/world-inequality-report-2022/ (accessed 10 March 2022).

Clarke, S (2005) The Neoliberal Theory of Society, available: https://homepages.warwick.ac.uk/~syrbe/pubs/Neoliberalism.pdf (accessed 14 March 2022).

Concord (2019) Inequalities Unwrapped – an urgent call for systemic change, available: https://concordeurope.org/resource/inequalities-unwrapped-an-urgent-call-for-systemic-change/ (accessed 27 January 2022).

Daly, T, Regan, C and Regan, C (2017) Learning to Change the World: an audit of development education resources 2013-2016, Bray: DevelopmentEducation.ie, available: https://developmenteducation.ie/resource/learning-change-world-audit-development-education-resources-ireland-2013-2016/ (accessed 1 March 2022).

Darnton, A and Kirk, M (2011) Finding Frames: New ways to engage the UK public in global poverty, London: Bond, available: https://www.bridge47.org/sites/default/files/2018-12/finding_frames.pdf (accessed 10 March 2022).

DE Web (2022a) Irish Aid GCE Strategy 2021-2025: https://irishaid.ie/media/irishaid/publications/Global-Citizenship-Education-Strategy.pdf

DE Web (2022b) Dóchas development education working group (Background and Principle Objectives): https://www.dochas.ie/assets/Files/DEG-ToR.pdf

DE Web (2022c) IDEA Vision 2025: https://irp.cdn-website.com/9e15ba29/files/uploaded/IDEA_Vision2025_DigitalPlusCover_0107.pdf

(accessed at various dates from mid-January to mid-March 2022).

Dobre I C (2019) ‘The Influence of Neoliberalism in Europe’, in Ovidius University Annals, Economic Sciences Series, Ovidius University of Constantza, Faculty of Economic Sciences, Vol. 0, No. 1, pp. 190-194, August, available https://ideas.repec.org/a/ovi/oviste/vxixy2019i1p190-194.html (accessed 28 March 2022).

Dóchas (2020) International Development and Humanitarian Action in a Time of COVID-19, available: https://www.dochas.ie/assets/Dochas-Policy-Brief_FINAL_150520.pdf (accessed 28 February 2022).

Dorn, G W (1997) ‘Book Review: Pinochet’s Economists: The Chicago School in Chile’, The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 77, No. 4, available: https://read.dukeupress.edu/hahr/article-standard/77/4/745/144780/Pinochet-s-Economists-The-Chicago-School-in-Chile (accessed 10 March 2022).

Eagleton-Pierce, M (2016) Neoliberalism: The Key Concepts, Abingdon (Oxon) and New York (NY): Routledge.

EU DEAR (n.d.) available: https://dear-programme.eu/map/?map_menu=map_projectslist (accessed 14 March 2022).

European Commission (2019) Commission Staff Working Document: Implementation of the new European Consensus on Development – addressing inequality in partner countries, available: https://eudevdays.eu/sites/default/files/swd_inequalities_swd_2019_280.pdf (accessed 28 February 2022).

European Commission (2021) Thematic Programme for Civil Society Organisations: Multiannual Indicative Programme 2021-2027, available: https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/system/files/mip-2021-c2021-9158-civil-society-organisations-annex_en.pdf (accessed 28 February 2022).

European Union (2017) The New European Consensus on Development: Our World, Our Dignity, Our Future, available: https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/system/files/european-consensus-on-development-final-20170626_en.pdf (accessed 27 January 2022).

Freire, P (1970) [1996] Pedagogy of the Oppressed, London: Penguin Books.

Fricke, H J, Gathercole, C and Skinner, A (2015) Monitoring Education for Global Citizenship – a contribution to debate, Brussels: CONCORD DEEEP, available: https://www.academia.edu/11225383/Monitoring_Education_for_Global_Citizenship_A_contribution_to_debate (accessed 10 March 2022).

Friedman, M (1951) ‘Neo-Liberalism and its Prospects’ (originally published in Farmand, 17 February, pp. 89-93) in R Leeson and C G Palm (eds.) (n.d.) The Collected Works of Milton Friedman, available: https://miltonfriedman.hoover.org/internal/media/dispatcher/214957/full (accessed 13 January 2022).

Goldin, I (2016) The Pursuit of Development: Economic growth, social change and ideas, Oxford UK: Oxford University Press.

Green, D (2016) How Change Happens, Oxford UK: Oxford University Press.

Hanvey, R G (1976) [2004] An Attainable Global Perspective, New York: The American Forum for Global Education, available: https://www.coursehero.com/file/93285534/An-Attainable-Global-Persperspectivepdf/ (accessed 13 January 2022).

Harriss, J (2019) ‘Great promise, hubris and recovery: a participant’s history of development studies’ in U Kothari (ed.) A Radical History of Development Studies: Individuals, institutions and ideologies, London: Zed Books.

Harvey, D (2019) Spaces of Global Capitalism, London and New York: Verso.

Hope, A and Timmel, S (1984) Training for Transformation: A handbook for community workers (3 vols.), Gweru ZW: Mambo Press.

IDEA (n.d.) Code of Good Practice for Development Education: 12 core principles, available: https://irp.cdn-website.com/9e15ba29/files/uploaded/15538_IDEA%20Code%20of%20Good%20Practice_Leaflet_WEB%20Final.pdf (accessed 13 January 2022).

ID Web (2022):

ActionAid: https://actionaid.ie/about-us/what-we-do/; https://actionaid.ie/take-action/

Children in Crossfire: https://www.childrenincrossfire.org/what-we-do/

Christian Aid: https://www.christianaid.ie/about-us/our-aims

Concern Worldwide: https://www.concern.net/what-we-do

Dóchas: https://www.dochas.ie/about/

Irish Aid: https://www.irishaid.ie/what-we-do/

Oxfam: https://www.oxfamireland.org/provingit/issues-we-work-on

Plan International: https://www.plan.ie/about-plan/what-we-do/

Trócaire: https://www.trocaire.org/about/

UNICEF: https://www.unicef.ie/about/our-story/

World Vision: https://www.worldvision.ie/about/world-vision/

(accessed at various dates from mid-January to mid-March 2022).

Irish Aid (n.d. a) A Better World: Ireland’s Policy for International Development, available: https://www.irishaid.ie/media/irishaid/aboutus/abetterworldirelandspolicyforinternationaldevelopment/A-Better-World-Irelands-Policy-for-International-Development.pdf (accessed 27 January 2022).

Irish Aid (n.d. b) Global Citizenship Education Strategy 2021-2025, available: https://irishaid.ie/media/irishaid/publications/Global-Citizenship-Education-Strategy.pdf (accessed 27 January 2022).

Ishii, Y (2003) Development Education in Japan: A comparative analysis of the contexts for its emergence and its introduction into the Japanese school system, New York and London: Routledge Falmer.

Kingham, T and Coe, J (2005) The Good Campaigns Guide: Campaigning for impact, London: NCVO Publications.

Lattimer, M (1994) The Campaigning Handbook, London: Directory of Social Change.

Leeson, P F (1988) ‘Development Economics and the Study of Development’ in P F Leeson and M Minogue (eds.) Perspectives on Development: Cross-disciplinary themes in development, Manchester (UK): Manchester University Press.

Lissner, J (1977) The Politics of Altruism: A study of the political behaviour of voluntary development agencies, Geneva: Lutheran World Federation.

Oxfam (2022) Inequality Kills: The unparalleled action needed to combat unprecedented inequality in the wake of COVID-19, available: https://www.oxfamireland.org/sites/default/files/bp-inequality-kills-170..., also see: https://www.oxfamireland.org/blog/ten-richest-men-double-their-fortunes-pandemic-while-incomes-99-percent-humanity-fall (accessed 27 February 2022).

Pike, G and Selby, D (1988) Global Teacher, Global Learner, London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Polanyi Levitt, K (2022) ‘Unravelling the canvas of history’ in H Veltmeyer and P Bowles (eds.) The Essential Guide to Critical Development Studies (2nd edition), Abingdon (Oxon): Routledge.

Ramalingam, B (2013) Aid on the Edge of Chaos: Rethinking international cooperation in a complex world, Oxford UK: Oxford University Press.

Regan, C and Sinclair, S (2002) ‘Engaging the Story of Human Development – the world view of human development’ in C Regan (ed): 80:20 Development in an Unequal World, Bray (IE) and Birmingham (UK): 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World and Tide.

Rowden, R (2016) The IMF Confronts Its N-Word, available: https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/07/06/the-imf-confronts-its-n-word-neoliberalism/ (accessed 10. March 2022).

Taylor-Gooby P and Leruth B (2018) ‘Individualism and Neo-Liberalism’ in P Taylor-Gooby and B Leruth B (eds.) Attitudes, Aspirations and Welfare: Social Policy Directions in Uncertain Times, Palgrave Macmillan, available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326026212_Individualism_and_Neo-Liberalism (accessed 21 June 2022).

Tide (1995) Development Compass Rose: Consultation Pack, Birmingham: Development Education Centre, available: https://www.tidegloballearning.net/resources/development-compass-rose-consultation-pack (accessed 27 May 2022).

Trócaire (2018) Food Democracy: feeding the world sustainably, available: https://www.trocaire.org/sites/default/files/resources/policy/food_democracy_policy_paper_final_pdf.pdf (accessed 27 February 2022).

Van Waeyenberge, E (2022) ‘The post-Washington consensus’ in H Veltmeyer and P Bowles (eds) The Essential Guide to Critical Development Studies, London and New York: Routledge

Veltmeyer, H and Bowles, P (eds.) (2022) The Essential Guide to Critical Development Studies, London and New York: Routledge.

Williamson, J (1990) ‘What Washington Means by Policy Reform’ in J Williamson (ed.) Latin American Adjustment: how much has happened?, Washington DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, available: https://allenbolar.files.wordpress.com/2017/02/williamson-john-1990-what-washington-means-by-policy-reform.pdf (accessed 10 March 2022).

Williamson, J (2002) Did the Washington Consensus Fail?, available: https://www.piie.com/commentary/speeches-papers/did-washington-consensus-fail (accessed 10 March 2022).

World Bank (2020) World Development Report 2020: Trading for development in the age of global value chains, Washington DC: The World Bank.

World Inequality Lab (2022) available: https://inequalitylab.world/en/ (accessed 29 July 2022).

Harm-Jan Fricke is a Development Education/Global Learning consultant working with local, national and international organisations in the UK and Europe on design, implementation and evaluation of projects and programmes in support of local-global development: www.linkedin.com/in/hjfricke