Women on the Frontlines of Resistance to Extractivism

Development Education and Gender

Abstract: We are living in extreme times with planetary boundaries being breached and our current economic model pushing life to collapse. The pressure to switch to renewable energy can no longer be avoided. However, many industry actors want to continue with our current economic model and simply switch the energy source. For this to happen, mining needs to increase dramatically. Rural and indigenous communities are disproportionately impacted by mining and other extractive industries, with severe negative consequences on local livelihoods, community cohesion and the environment. In this article we will explore the gendered impacts experienced by these communities, which see women facing the worst impacts of a neoliberal extractive agenda. Conversely, women are leading the resistance to extractivism and stepping outside of traditional gender roles to be leaders in movements fighting destructive extraction. We will draw upon examples from the Americas, through a lens of ecofeminism and feminist political ecology, to explore how the women of these movements are demanding systematic change to the paradigms of capitalism, colonialism and patriarchy – highlighting that these forms of domination are connected and thus, need to be eliminated together.

Key words: Ecofeminism; Feminist Political Ecology; Extractivism; Resistance; Climate Change; Neoliberalism; Gender; Americas.

Introduction

Our globe is facing climate chaos. Humans are confronted with their biggest existential threat ever. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Special Report, published in October 2018 (IPPC, 2018), asserted that we have just 12 years to make dramatic changes if we are to avoid catastrophic climate change. Students, the world over, are walking out of their educational institutions to demand that adults begin taking their future seriously (Laville, Noor & Walker, 2019). Global education, consequently, has a vital role to play in encouraging exploration of, and engagement in, this high priority topic. To begin with, global educators are best placed to teach about the causes and impacts of the climate crisis and the linkages to global inequality and injustice (Hitchcock, 2019:7). Secondly, the educational process can provide a structure through which students can learn about current, and develop new, solutions to the crisis. Additionally, by encouraging the participation of students in the climate strike in a safe and educational way, educators are facilitating ‘an excellent learning experience through which students can develop key thinking skills, capabilities, attitudes and dispositions that will develop them as “contributors to society and the environment”’ (McCloskey, 2019).

Delving deeper into the complex issue of solutions to the climate crisis, one oft-quoted solution is renewable energy, which has already been incorporated into government policies (McNaught et al., 2013) and the Northern Ireland curriculum (Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment, 2016; 2018). Solar, wind, hydro, bio-fuels, these are some of the developments given by technology that are cited as healthy alternatives to our dependence on fossil fuels. The burning of fossil fuels is one of the main contributors to the planetary crisis, producing carbon and other greenhouse gases (Nunez, 2019). The need to switch to renewable energy can no longer be ignored. However, the journey there is crucial and global education should highlight the intricacies of this. If we leave untouched the system that brought us to breaking point then we will ultimately assimilate renewable energy into the neoliberal agenda based on deregulation, privatisation and a ‘free market’ economy (Ostry, Loungani & Furceri, 2016). Thus, our future will be premised on old distortions, carrying over social, economic and environmental injustices into new structures that will alleged save the planet (Hitchcock, 2019:11).

To illustrate this, we follow through what it means to retain our current economic model, forever wanting, forever consuming, and simply switch the energy source to renewables. For this to happen, mining needs to increase dramatically (Dominish, Florin and Teske, 2019: 5). Rare earth metals especially, and other metals such as copper, will be in high demand as they are key components in solar panels, batteries, electric cars etc. To date those most affected by mining and other extractive industries are rural and indigenous communities in the global South (Trócaire, 2019: 13), with severe negative consequences on local livelihoods, community cohesion and the environment. If we continue with business as usual, which means more extraction, it will be these communities who will suffer the most. For example, a recent World Bank study identified Latin America, Africa and Asia as key targets going forward for rare earth and other critical metals (World Bank, 2017). There is also a gendered dimension to the impacts of mining, with women more affected than men, for reasons that we will explore in this article. Thus, extraction to satisfy the demand for renewables within the neoliberal system will further discriminate against women.

However, by looking at how women are resisting destructive extraction, and drawing on the theories of ecofeminism and feminist political ecology, we can see how, through the essence of their resistance, women, and especially indigenous and rural women, are leading the way out of the trap. This article will draw on examples from the Americas to show how women from movements in this region are demanding a systematic change to the paradigms of capitalism, colonialism and patriarchy, highlighting how these forms of domination are connected and, thus, need to be eliminated completely. We conclude with practical suggestions as to how these themes could be incorporated into an educational setting.

What is extractivism?

Extractivism can be defined as ‘activities that remove large volumes of non-processed natural resources (or resources that are limited in quantity), particularly for export’ (Acosta, 2017: 81). It is often tied up with transnational capital, the state and neoliberal agendas. But it is much more than that; it is a way of seeing the world. Klein, (2015: 169) calls extractivism, a ‘dominance-based relationship with the earth, one of purely taking’, which is ‘the opposite of stewardship’. The main forms of extractivism are mining, quarrying and oil and gas extraction (including fracking). However, deforestation and industrial agriculture are also sometimes considered forms of extractivism as they extract resources from the land causing severe ecological depletion. Hitchcock (2019: 9) further explains extractivism as ‘high-intensity, export-oriented extraction of common ecological goods rooted in colonialism and the notion that humans are separate from, and superior to, the rest of the living world’.

Theoretical framework

Ecofeminism and Feminist Political Ecology

The closely related ecological feminist approaches of socialist/materialist ecofeminism (Merchant, 1980; Mellor, 1992; Plumwood, 1993; Warren, 1997; Federici, 2004; Gaard, 2015) and feminist political ecology (herein, FPE) (Agarwal, 1992, 2001; Rocheleau, Thomas-Slayter & Wangari, 1996; MacGregor, 2006, 2010, 2013; Salleh, 2009; Elmhirst, 2011; Sultana, 2011, 2013; Veuthrey & Gerber, 2012; Resurreccion, 2013) offer a fertile perspective to understand extractivism. FPE ‘re-engages and rethinks neoliberal extractivism and violence through our analysis of our experience of diverse nature-cultures as part of a collective and ongoing process of decolonising development practices, political ecology and feminism’ (Harcourt & Nelson, 2015: 23). Political ecology reminds us that human-environment relationships are mediated by wealth and power. It links political, economic and social factors with environmental change. FPE, therefore, adds a gendered analysis to these processes.

Ecofeminism is a reaction to how women and nature have been marginalised in modern patriarchal society, and highlights that all types of domination (capitalism, colonialism, patriarchy) are connected, therefore, one cannot be eliminated without the others. Materialist and socialist ecofeminists have rejected the essentialism of any special or biological link between women and nature as proposed by spiritual ecofeminists (Diamond & Orenstein, 1990). Instead they locate the oppression of women and nature in capitalist patriarchal structures and the exploitative relations of capitalist production, connecting the exploitation of resources to the degradation of nature and women (Merchant, 1980; Mies, 1981; Federici, 2004). This approach also recognises that both categories are socially constructed and in such a way that devalues them.

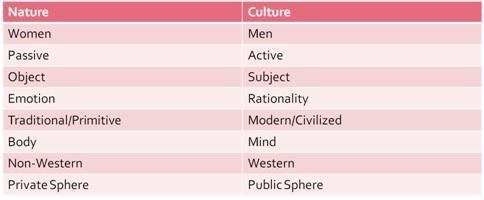

Table 1: Dualistic thought structures (Cirefice and Sullivan)

Ecofeminists have located the root of extractive ecological exploitation and social injustices in the patriarchal capitalist worldview that emerges from the Cartesian dualism (Merchant, 1980; Shiva,1989; Plumwood, 1993). The roots of the subjugation of women and nature are embedded in modern knowledge, which is dualistic and developed during the Enlightenment period. This era saw the rise of the scientific and industrial revolutions and capitalism, and so ecofeminists critique the knowledge these ‘progresses’ are based on. René Descartes established the Cartesian dualism of mind and body which extended to others, such as, culture/nature, man/woman, civilised/primitive (Merchant, 1980), as seen in table 1. Ecofeminists argue this worldview is detrimental for nature, women and indigenous communities who are placed on the ‘passive’ or ‘object’ side of the dualism, implying they are resources, which are lacking in agency (Plumwood, 1993). Women become ‘viewed as the “other”, the passive non-self’ (Shiva, 1989: 14), hence, ecofeminists emphasise the agency of all humans and nonhumans who have been oppressed under this Cartesian division of the world. Ecofeminists see the legacy of these thought structures continuing into extractive capitalist exploitation today, in which both women and nature become ‘othered’ to justify seeing them as inanimate resources.

In the Cartesian worldview we see the objectification of the earth and devaluation of the frontline communities who suffer the worst impacts of extraction (Jewett & Garavan, 2018), with extraction points considered as peripheral, as ‘sacrifice zones’ (Ashwood & MacTavish, 2016; Klein, 2015). Many indigenous perspectives have highlighted that the opposite to extractivism is ‘deep reciprocity; it’s respect, it’s relationship, it’s responsibility and it’s local’ (Leanne Betasamosake Simpson quoted in Di Chiro, 2015: 217). Ecofeminism and FPE argue that the notion that nature is separate from us is central to environmental crises (Plumwood, 1993), therefore, relational approaches are needed which re-emphasise interconnection (Whatmore, 2002; Crittenden, 2000; Salleh, 1997; Plumwood, 1993; Haraway, 1991, 2008). Ecofeminists and FPE theorists recognise that challenges to the oppressive world order seek to move from a dualistic, extractive, mechanistic, anthropocentric worldview to relations of an interconnected, relational and biocentric world. Thus, an ecofeminist and FPE lens can provide a useful critical theoretical frame through which to explore and investigate the experiences, practices and worldviews of activists involved in contesting extractive development processes. Both FPE and ecofeminism share an interest in the role of women in collective activism around environmental issues and how gender is configured in these struggles to redefine environmental issues by including women’s knowledge, experience and interests (Moeckli & Braun, 2001: 123).

Why are women disproportionately impacted?

Most of the socio-environmental costs of the extractive industry are felt by the rural populations of extractive regions, however women are often disproportionately impacted (Barcia, 2017). The benefits of resource extraction include employment, although most jobs are held almost exclusively by men. The negative effects, however, are felt in the household, where due to gender socialisation, women have the most responsibility (Federici, 2004). The gender division of labour brings women in contact with natural resources and the environment for subsistence. Women, as primary care-givers, have a material connection as key stakeholders in farming and managing natural resources, as well as household consumption (MacGregor, 2006; Martinez-Alier, 2002; Agarwal, 1992). Therefore, when extraction impacts the local environment, women are on the frontline of its impacts. For example, water resources can be poisoned and drained, mine blasting can create problems such as air pollution and damage to housing, and there is an associated increase in alcoholism and domestic violence (Gies, 2015). These impacts are especially felt by indigenous communities who rely on natural resources for their subsistence economy; for hunting, fishing, foraging, medicine and culture. Moreover, in the Americas, indigenous people, particularly women, are further disadvantaged by societal and economic problems as a result of colonialism, such as poverty and marginalisation, a lack of power and land rights and a limited influence on decision making (Smith, 1997; Nestra, 1999).

Therefore, it is women’s material conditions which push them to resist. For example, in Guatemala, the Kaqchikel women’s movement see their activism as ‘care work’. The environmental destruction impacts most on reproductive work which is done by women. Women are involved in this not due to some natural or essentialist characteristic which makes women more caring, but because they are conditioned to be caregivers through a process of gendered socialisation. The Kaqchikel women are critical of the ways in which care work overburdens women, their movements want to see a re-valuing and redistribution of care work in society (Hallum-Montes, 2012: 115). Women’s resistance needs to be understood in relation to gender relations and resource management and use and not idealised. From this vantage point, relationships with the environment are gendered due to the division of labour and socialised gender roles, following which, gendered understandings of environmental change need to integrate subjectivities, scales, places, and power relations (Sultana, 2013: 374). By questioning essentialising discourses, FPE perspectives can be critical of narratives that romanticise women as having a special innate relationship to the environment which naturalises their reproductive work and resistance.

Patriarchy’s disregard for nature, women and indigenous people is further compounded by colonial legacies which impact on the bodies of indigenous women (Smith, 2003: 81). The attack on nature by mining industries can also impact on indigenous women’s bodies as the effects of radiation poisoning are most apparent on women’s reproductive systems with impacts such as increased cases of ovarian cancer, miscarriages and birth defects (Smith, 2003: 82). In the Blackhills, in the United States (US), women on the PineRidge reservation experience a miscarriage rate six times higher than the national average (Smith, 1997: 23). The same conceptual framework of thought that commodifies and exploits nature can be extended to women’s bodies and in this case, indigenous women.

Studies have also drawn the link between sexual violence and the mining industry (Cane, Terbish & Bymbasuren, 2004) which will be explored further later. Women who resist extraction, standing up for their communities, lands and environment are often the targets of gender specific violence and threats (Barcia, 2017). In many ways they are challenging not only corporate power but patriarchal structures and gender norms (Barcia, 2017: 5; Willow and Keefer, 2015). Smith (2003) believes indigenous women’s bodies threaten the legitimacy of coloniser states like the US because of their ability to reproduce and continue resistance. She sees colonialism as structured on the logic of sexual violence; colonised people are projected as body as opposed to mind, much in the same way colonised nature is seen as raw materials without agency (Smith, 2003: 82). Both nature and women are understood as the passive ‘Other’ and a commodity to be exploited.

Women on the Frontlines

Why are (indigenous) women on the frontlines fighting a neoliberal extractivist agenda?

Many of the accounts above portray women as passive victims, reinforcing dualistic thought structures which place women on the passive, object side of the dualism. Therefore, highlighting the agency of women, their subjectivity, resistance and activism becomes paramount. Ecofeminism highlights the link between the abuse of earth and suppression of women, but there is also a strong link between empowerment and activism of women and the healing of the earth. Examples of this include The Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN, 2019) which has many campaigns and groups in the Americas and around the world connecting women’s solutions and resistance to extractive industries. Also, in September 2015, the Indigenous Women of the Americas signed a Defend Mother Earth Treaty against extractive industry (Indigenous Rising, 2015). It stated that:

“While opposing extractive industries, women human rights defenders are advancing alternative economic and social models based on the stewardship of land and common resources in order to preserve life, thereby contributing to the emergence of new paradigms” (Barcia, 2017:12).

This alternative worldview is seen in the following case studies which highlight the agency of women in their resistance to social and environmental injustice. There is a huge political and practical significance to the hundreds of women who initiated protests and grassroots organising activities for both women and nature (Warren, 1997:10). As previously outlined, women are often prime movers in protecting the environment not because they have some special essentialist link to it but because in many cases they are affected the most by environmental destruction. Similarly, women often play a primary role in community action because it’s within the domestic sphere, a domain related to women due to gender norms. Women are providing small scale solutions with large impacts while reclaiming power at the local level (Hamilton, 1991).

FPE literature has critiqued the fact that a focus on women as environmental saviours can lead to an increased environmental responsibility and unpaid work for women (MacGregor, 2013). FPE adds to debates by highlighting the need for context specific accounts of gender and material realities to avoid homogenising women, romanticising their resistance or placing unwanted responsibility on them for creating solutions. The stereotype of women as environmental victims or as environmental caretakers can contradict the complex daily reality of resource use, power and negotiation (Resurrección, 2013). Further, by glorifying indigenous women’s movements it is easy to hide the other elements of reality that are not so glorious: the violence, poverty and exhaustion they face on a day to day basis (Lind, 2003).

It remains important, therefore, to counter the narrative of rural and indigenous women as powerless victims of environmental change with no mention of their life experiences, their struggles, resistances or alliances (Dey, Resurreccion & Doneys, 2014: 946). Indigenous women’s activism against extractive industry and environmental degradation is diverse and needs to be understood in relation to the social, historical, political and economic setting in which it is embedded. These resistances are demanding systematic change to the paradigms of capitalism, colonialism and patriarchy and demanding respect and protection of women’s bodies, land, water, mother earth, culture and community (Gies, 2015). The next section provides examples from the Americas, through a lens of ecofeminism and feminist political ecology, that explore how women are demanding systematic change to the paradigms of capitalism, colonialism and patriarchy.

Case studies from around the Americas

North American- Indigenous women resist

Honor the Earth is an organisation set up by indigenous ecofeminist Winona LaDuke. This organisation highlights the interconnectedness of the domination of nature, indigenous people and women. Honor the Earth has a campaign against sexual violence in extraction zones. They state that there is an epidemic of sexual violence perpetrated against indigenous women driven by extreme extraction in the Brakken oil fields, North Dakota and the Tar Sands of Alberta. In these locations the violations against the earth run parallel to the violation of human rights. They requested a formal intervention by the United Nations (UN) and their submission document contextualises the relationship between oil booms and sex trafficking booms within broader historical processes of colonialisation and genocide (Memee Harvard, 2015).

This campaign argues that the same conceptual framework which commodifies and exploits nature can be extended to (indigenous) women’s bodies. Studies have drawn the link between sexual violence and the mining industry (Cane, Terbish & Bymbasuren, 2014; Memee Harvard, 2015; Farley et al., 2011). Sex trafficking, which disproportionally affects indigenous women in North America, is higher near points of extraction where there are large camps of temporary, highly paid male labour (Memee Harvard, 2015). Gies (2015) highlights that for the women involved in resisting extractive industry their fight against gender violence, that disproportionately affects indigenous women, is integral to their struggle. Canadians highlight that in their country over 4,000 murdered and missing indigenous women have been largely uninvestigated (Ibid).

Indigenous women’s resistance in Canada is strong too; the Mining Injustice Solidarity Network is made up of 90 percent women (Ibid). Further, women are at the heart of the Klabona Keepers, a society formed by Tahltan Elders, fight to protect the ecologically sacred headwaters in northern British Colombia from mining contamination (Roy, 2019). As well as protecting the right to their ancestral lands, they are also protecting the biodiversity they depend on for hunting, fishing and foraging for their livelihood (Gies, 2015). The Unist’ot’en blockade camp is led by Freda Hudson and stands against oil and gas pipelines coming from the Tar Sands operation in Alberta. The proposed pipeline would encroach on the Witsuwit'en people’s unceded territory (Temper, 2019). They have created a border to their un-surrendered land, and demand that their consent is needed to go there. This is a right enshrined by the UN Declaration of Indigenous Peoples which they reinforce (Toledano, 2014).

Mining has had a key role in Indian-settler relations from as early as the 17th century (Ali, 2003: 6). It is closely tied to issues of colonialism and how indigenous people were erased from their lands (Braun, 2000; Stanley, 2013). The construction of a wilderness, available for exploitation, was seen by colonial powers as completely separated from human, cultural influence. This impression of empty, virgin land, legally justified its confiscation by the Terra Nullius Act (Stanley, 2013). Moreover, the land was often gendered in colonial accounts and was represented as a feminine space with successful use of the wilderness compared to acts of sexual conquest and rape. It also enabled mining companies to capitalise on aboriginal unemployment and use their lands and bodies as waste sinks (Stanley, 2013: 211).

As environmental destruction from mining can be regarded as a form of colonialism and racism which has marked Indian/ White relations since the arrival of Columbus in 1492 (Halder, 2004: 103), the environmental impacts of mining cannot be examined without also considering their impacts on indigenous culture and bodies. Indigenous peoples have strong cultural and social links to their land (O’Faircheallaigh, 2013: 1792). Because of this, native people need high levels of environmental quality to meet not only physical but spiritual needs. As these religious rights are inseparable from environmental protection, this makes the indigenous case different from environmental racism in other contexts (Nestra, 1999: 114). Mining can have devastating effects on the environment and can compromise native culture and social life as sites of cultural significance are sometimes destroyed (O’Faircheallaigh, 2013: 1791).

Studies of environmental racism have shown how native lands are frequently used as sites of mining, toxic dumps and nuclear and military testing (Nestra, 1999: 114). In North America, 60 percent of energy resources are found on Indian land (Smith, 1997: 22), and are frequently threatened by capitalist operations. For example, the Blackhills, home to the Lakota Sioux, has faced many problems relating to mining. When gold was discovered in 1875 and by 1877 on their land, the Sioux lost their land rights (Halder, 2004: 108).

Latin America

Gender based violence and extractive activities in Latin America often go hand in hand. One example is the case of Margarita Caal Caal, an indigenous woman, one of ten women gang raped and then forcibly evicted from their homes in a village in Lote Ocho, Guatemala, by a Canadian mining firm (Daley, 2016). Mrs. Caal has taken her case to the Canadian courts to demand justice for what she suffered. So, the feminist environmental struggles see this violence as a result of the same oppressive systems (capitalism, colonialism, patriarchy) that exploit the earth. It is these connections between physical and sexual violence against women and the exploitation of the land which informs their resistance (Gies, 2015).

In 2015, six indigenous Mapuche women in Argentina, at the heart of a fight against fracking, chained their bodies to fracking drills in protest. Moreno (2016) argues that these women face a triple intersectional threat as indigenous, women and workers of the earth. In their worldview there is no division of nature and culture (Moreno, 2016), unlike the logic of capitalism (Klein, 2014; Bauhardt, 2013; Federici, 2004) which is embedded in this dualism (see table 1). In the Mapuche language of these indigenous women there is no concept equivalent to natural resource, there is no need to accumulate a surplus, and the natural world is inseparable from the social world (Moreno, 2016). Ecofeminists point out that women struggle against extractivism because this system is based on a mechanistic rationality historically associated with masculinity (see table 1) and positioned as superior to non-rational ways connected to feeling, the earth and taking care of life (Moreno, 2016). For these struggles there is no separation between production and reproduction, land and life, resistance and survival, and that is why women take on leadership roles in defending their territory and fighting gendered oppression (Gies, 2015).

Feminist approaches have highlighted that the personal is political and so link processes at differing scales from the household and body to the national, international and global (Monhanty, 2007; Truelove, 2011). In her study with indigenous Kaqchikel women in Guatemala, Hallum-Montes (2012) highlighted that the women saw a link between challenging domestic violence and the abuse of ‘Mother Earth’. These women who established the ‘Women United for the Love of Life’ group bring a gendered consciousness to their environmental activism and link their local activism to wider social movements.

These struggles are intersectional and so link environmental activism to issues of gender, race, class, opposing the interlocking systems of oppression and privilege and so they relate these systems of patriarchy, colonialism and racism to their everyday lives (Hallum-Montes, 2012: 105). The impacts of extractivism on women’s material subsistence structure their mobilisations against the extractive industries thus making visible the impacts of industrial capitalism on the environment and their own lives. They challenge power relations on many scales; between local poor communities and national elites and between men and women in their villages (Veuthey & Gerber, 2012: 620). Framing discussions about extraction only in technical environmental terms or only in relation to climate change can silence the social injustice, particularly gendered issues, which are sometimes connected to these projects. It also marginalises issues that are often most relevant to women’s lives, such as polluted water, increased gender violence or contaminated land and food insecurity.

Global Learning

The case studies set out above on women and extractivism can support further discussion on issues of gender, patriarchy, extractivism, colonialism, and neoliberalism. Exploring the essential link between these paradigms could make an invaluable contribution to global education. Debating the impact of extractivism on women, particularly indigenous activists, offers the opportunity to analyse factors underpinning oppression, empowerment and systemic change. Through the example of women, especially indigenous and rural women, young people can flesh out the meaning behind the popular chant often heard at the Youth for Climate Strikes: ‘system change, not climate change’. There are various tools and resources that could be employed to bring this issue to students. For example, the use of case studies to illustrate theory, as we have done, is a useful tool which can stimulate creative thinking, open-mindedness and empathy. Comhlámh, the Irish development non-governmental organisation (NGO), is producing a resource, called Digging Deeper, on extractivism in Peru and Ireland, which includes case studies of activists involved in mining conflicts from both countries. Also, Trócaire and The Future We Need have produced a mining toolkit entitled Digging At Our Conscience (The Future We Need, 2016).

Additionally, there are numerous visual aids that capture the complexities of gender and extractivism. From Peru, Las Damas Azules (ISF, 2015) showcases women involved in the defence of their land against mining and their reasons for becoming active in the resistance movement. Also, from Peru, La Hija de La Laguna (Cabellos, 2015), explores one woman’s spiritual connection with the water she is protecting, along with her community. From Bolivia, Abuela Grillo (The Animation Workshop, 2010) is a visually stunning short animation following the grandmother figure representing water who is threatened by a corporation who wants to bottle her tears which is based on the Water Wars in Bolivia in 2000 (Democracy Now, 2010).

Another avenue for global education on extractivism would be to link with organisations locally and globally who are working on these issues. Learners could be encouraged to organise a volunteer project or solidarity action with the communities in defence of their resources, land and rights. This would provide a form of experiential learning based on the realities of extractivism both locally and globally. Some Irish organisations operating in the Americas and working on extractivism are Latin America Solidarity Centre (LASC), Trócaire, Comhlámh and Friends of the Earth (country specific).

Conclusion

This article has explored extractivism through the framework of ecofeminism. It has considered how women and nature are dually exploited because they are seen as ‘other’ and without agency by the paradigms that underpin their exploitation; namely capitalism, colonialism and patriarchy. Furthermore, by not romanticising women’s involvement in the resistance against extractivism, but rather understanding it in terms of a division of labour and socialised gender roles, we escape the trap of inadvertently reinforcing these political, economic and social injustices. The case studies presented not only illustrate the violence the system imposes on women and nature, but also highlights the link between the empowerment and activism of women and the healing of the earth. Global education is well positioned to bring these issues to learners through the use of interactive and participative training methodologies that illustrate how the paradigms propping up the extractivist agenda are also driving us to the brink of climate chaos and mass extinction. We can make use of the educational space to explore the complexities and solutions to the crises our world is facing, as well as encouraging active projects of global citizenship, such as participation in the climate strikes or other forms of exercising their agency.

References

Acosta, A (2017) ‘Post-Extractivism: From Discourse to Practice- Reflections for Action’, International Development Policy, 9: 77-101.

Ali, S (2003) Mining, and the Environment, and Indigenous Development Conflicts, Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, pp.1-254.

Agarwal, B (2001) ‘Participatory exclusion, community forestry, and gender: an analysis for South Asia and a conceptual framework’, World Development, 29(10): 1623-1648.

Agarwal, B (1992) ‘The Gender and Environment Debate: Lessons from India’, Feminist Studies, 18(1): 119-158.

Ashwood, L & MacTavish, K (2016) ‘Tyranny of the majority and rural environmental injustice’, Journal of Rural Studies, 47: 271-277.

Barcia, I (2017) ‘Women Human Rights Defenders Confronting Extractive Industries An Overview of Critical Risks and Human Rights Obligations’, Creative Commons, available: https://www.awid.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/whrds-confronting_extractive_industries_report-eng.pdf (accessed 30 July 2019).

Braun, B (2000) ‘Producing vertical territory: geology and governmentality in late Victorian Canada’, Cultural Geographies, 7: 7-46.

Bauhardt, C (2013) ‘Rethinking gender and nature from a material(ist) perspective: Feminist economics, queer ecologies and resource politics’, European Journal of Women's Studies, 20(4): 361-375.

Cabellos (2015) Hija de la Laguna [Daughter of the Lake], available: https://www.netflix.com/gb/title/80160815, (accessed 27 September 2019).

Cane, I, Terbish, A & Bymbasuren, O (2014) ‘Mapping Gender Based Violence and Mining Infrastructure in Mongolian Mining Communities: Action Research Report for the Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining’, Gender Center for Sustainable Development Mongolia National Committee on Gender Equality Mongolia: University of Queensland, pp.1-40.

Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment (2016) ‘Lesson 3 – Renewables’, 3 June, available: http://ccea.org.uk/sites/default/files/docs/curriculum/area_of_learning/the_world_around_us/earth_science/future_earth/lesson3/LESSON_3_Renewables.pdf (accessed 16 October 2019).

Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment (2018) ‘Geography – Resources – Renewing our Energy Choices’, 22 June, available: http://ccea.org.uk/curriculum/key_stage_3/areas_learning/environment_and_society/geography (accessed 16 October 2019).

Crittenden, C (2000) ‘Ecofeminism Meets Business: A Comparison of Ecofeminist, Corporate, and Free Market Ideologies’, Journal of Business Ethics, 24(1): 51-63.

Daley, S (2016) ‘Guatemalan Women’s Claims Put Focus on Canadian Firms’ Conduct Abroad’, The New York Times, 2 April, available: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/03/world/americas/guatemalan-womens-claims-put-focus-on-canadian-firms-conduct-abroad.html?_r=0 (accessed 30 July 2019).

Democracy Now! (2010) ‘The Cochabamba Water Wars: Marcela Olivera Reflects on the Tenth Anniversary of the Popular Uprising Against Bechtel and the Privatization of the City’s Water Supply’, Democracy Now!, 19 April 2010, available: https://www.democracynow.org/2010/4/19/the_cochabamba_water_wars_marcella_olivera, (accessed 16 October 2019).

Di Chiro, G (2015) ‘A new spelling of sustainability: engaging feminist-environmental justice theory and practice’ in W Harcourt and I L Nelson (eds.) Practising Feminist Political Ecologies: Moving Beyond the ‘Green Economy’, London: Zed Books, pp.211-237.

Diamond, I & Orenstein, F (1990) Reweaving the World: The Emergence of Ecofeminism, San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, pp.1-319.

Dey, S, Resurreccion, B and Doneys, P (2013) ‘Gender and environmental struggles: voices from Adivasi Garo community in Bangladesh’, Gender, Place & Culture, 21(8): 945-962.

Dominish, E, Florin, N and Teske, S (2019) Responsible Minerals Sourcing for Renewable Energy, Institute for Sustainable Futures: University of Technology Sydney, available: https://earthworks.org/cms/assets/uploads/2019/04/MCEC_UTS_Report_lowres-1.pdf. (accessed 27 September 2019).

Elmhirst, R (2011) ‘Introducing new feminist political ecologies’, Geoforum, 42(2): 129-132.

Farley, M, Mathews, N, Deer, S, Lopez, G, Stark, C and Hudon, E (2011) ‘Garden of Truth: The Prostitution and Trafficking of Native Women in Minnesota’, Minnesota Indian Women's Sexual Assault Coalition and Prostitution Research & Education, available: http://www.mediawatch.com/?p=494. (accessed 30 July 2019).

Federici, S (2004) Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. Brooklyn: Autonomedia.

Gaard, G (2015) ‘Ecofeminism and climate change’, Women's Studies International Forum, 49: 20-33.

Gies, H (2015) ‘Facing Violence, Resistance Is Survival for Indigenous Women’, TeleSUR, 7 March, available: http://www.telesurtv.net/english/analysis/Facing-Violence-Resistance-Is-Survival-for-Indigenous-Women-20150307-0018.html (accessed 30 July 2019).

Halder, B (2004) ‘Ecocide and Genocide: Explorations of Environemental Justice in Lakota Sioux Country’ in D Anderson and E Berglund (eds.) Ethnographies of Conservation: Environmentalism and the Distribution of Privilege, New York & Oxford: Berghahn, pp.101-118.

Hallum-Montes, R (2012) ‘“Para el Bien Común” Indigenous Women's Environmental Activism and Community Care Work in Guatemala’, Race, Gender & Class, 19 (2): 104-130.

Hamilton, C (1991) ‘Women, home, and community’, Woman of Power, 20: 42–45.

Haraway, D (1991) Simians, Cyborgs and Women, London: Free Association.

Haraway, D (2008) When Species Meet, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Harcourt, W & Nelson, I L (2015) Practising Feminist Political Ecologies: Moving Beyond the ‘Green Economy’, London: Zed Books.

Hitchcock Auciello, B (2019) ‘A Just(ice) Transition is a Post-Extractive Transition: centering the extractive frontier in climate justice’, War on Want and London Mining Network: London, available: https://waronwant.org/sites/default/files/Post-Extractivist_Transition_WEB_0.pdf (accessed 27 September 2019).

Indigenous Rising (2015) ‘First Ever Indigenous Women's Treaty Signed of “North and South”’, Indigenous Rising, 30 September, available: https://indigenousrising.org/womens_treaty/ (accessed 30 July 2019).

Ingeniería Sin Fronteras (ISF) (2015) Las Damas Azules, [The Blue Ladies], available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=REf3LIo7MvE (accessed 27 September 2019).

IPPC (2018) ‘Summary for Policymakers of IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C approved by governments’, available: https://www.ipcc.ch/2018/10/08/summary-for-policymakers-of-ipcc-special-report-on-global-warming-of-1-5c-approved-by-governments/. (accessed 1 August 2019).

Jewett, C & Garavan, M (2018) ‘Water is life – an indigenous perspective from a Standing Rock Water Protector’, Community Development Journal, available: https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsy062. (accessed 7 February 2019).

Klein, N (2015) This Changes Everything, New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

Laville, S, Noor, P and Walker, A (2019) ‘‘It is our future’: children call time on climate inaction in UK’, The Guardian, 15 February 2019, available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/feb/15/children-climate-inaction-protests-uk. (accessed 15 October 2019),

Lind, A (2003) ‘Feminist Post-Development Thought: “Women in Development” and the Gendered Paradoxes of Survival in Bolivia’, Women's Studies Quarterly, 31 (4): 227-246.

MacGregor, S (2006) Beyond Mothering Earth: Ecological Citizenship and the Politics of Care, Vancouver: University of British Colombia Press.

MacGregor, S (2010) ‘Gender and Climate Change: From impacts to discourses’, Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, 6(2): 223–238.

MacGregor, S (2013) ‘Only Resist: Feminist Ecological Citizenship and the Post-politics of Climate Change’, Hypatia, 29(3): 617-633.

Martinez-Alier, J (2002) The Environmentalism of the Poor: A Study of Ecological Conflicts and Valuation, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

McCloskey, S (2019) ‘Global Youth Climate Strike 20th September - Guidance for Principals’, Centre for Global Education, 13 September, available: https://www.globallearningni.com/news/global-youth-climate-strike-20th-september-guidance-for-principals (accessed 16 October 2019).

McNaught, C, Kay, D, Hill, N, Johnson, M, Haydock, H, Doran, M and McCullough, A (2013) ‘Envisioning the Future: Considering Energy in Northern Ireland to 2050’, Ricardo-AEA and Action Renewables, 24 July 2013, available: https://www.economy-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/deti/2050%20vision%20report.pdf (accessed 16 October 2019).

Mellor, M (1992) Breaking the Boundaries: Towards a Feminist Green Socialism, London: Virago Press.

Memee Harvard, D (2015) ‘Submission to the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, Fourteenth Session’, Honor the Earth, available: http://www.honorearth.org/sexual_violence. (accessed 30 July 2019).

Merchant, C (1980) The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution, New York: Harper and Row.

Mies, M (1981) ‘Dynamics of Sexual Division of Labour and Capital Accumulation: Women Lace Workers of Narsapur’, Economic and Political Weekly, 16 (10): 487-500.

Moeckli, J & Braun, B (2001) ‘Gendered Natures: Feminism Politics and Social Nature’ in N Castree and B Braun (eds.) Social Nature Theory, Practice and Politics, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, pp.112-132.

Mohanty, C (2007) Feminism Without Borders, Longueuil, Québec: Point Par Point.

Moreno, N P (2016) ‘Six Indigenous women at the heart of fracking resistance in Argentina’, TeleSUR, 29 March, available: https://intercontinentalcry.org/argentina-6-indigenous-women-heart-fracking-resistance/ (accessed 30 July 2019).

Nestra, L (1999) ‘Environmental Racism and First Nations of Canada: Terrorism at Oka’, Journal of Social Philosophy, 30(1): 103-124.

Nunez, C (2019) ‘Fossil fuels, explained’, National Geographic, 2 April, available: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/energy/reference/fossil-fuels/ (accessed 16 October 2019).

O’Faircheallaigh, C (2013) ‘Women's absence, women's power: indigenous women and negotiations with mining companies in Australia and Canada’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36(11): 1789-1807.

Ostry, J, Loungani, P and Furceri, D (2016) ‘Neoliberalism: Oversold?’, Finance & Development, 53(2): 38-41, available: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2016/06/pdf/ostry.pdf (accessed 16 October 2019).

Plumwood, V (1993) Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, London: Routledge.

Resurrección, B (2013) ‘Persistent women and environment linkages in climate change and sustainable development agendas’, Women’s Studies International Forum, 40: 33-43.

Rocheleau, D, Thomas-Slayter, B and Wangari, E (1996) Feminist Political Ecology: Global Issues and Local Experiences, London: Routledge.

Roy, S (2019) ‘“I live off this land” Tahltan women and activism in northern British Columbia’, Women’s History Review, 28(1): 42-56.

Salleh, A (2009) Eco-Sufficiency and Global Justice: Women write political ecology, London: Pluto Press.

Salleh, A (1997) Ecofeminism as Politics, London: Zed Books.

Shiva, V (1989) Staying Alive: Women, Ecology and Development, London: Zed Books Ltd.

Smith, A (1997) ‘Ecofeminism through an Anti-colonial Framework’ in K Warren (ed.) Ecofeminism: Women, Culture and Nature, Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, pp.21-37.

Smith, A (2003) ‘Not an Indian Tradition: The Sexual Colonization of Native Peoples’, Hypatia, 8(2): 70-85.

Stanley, A (2013) ‘Labours of land: domesticity, wilderness and dispossession in the development of Canadian uranium markets’, Gender, Place & Culture, 20(2): 195-217.

Sultana, F (2013) ‘Gendering Climate Change: Geographical Insights’, The Professional Geographer, 66(3): 372-381.

Sultana, F (2011) ‘Suffering for water, suffering from water: Emotional geographies of resource access, control and conflict’, Geoforum, 42(2): 163-172.

Temper, L (2019) ‘Blocking pipelines, unsettling environmental justice: from rights of nature to responsibility to territory’, Local Environment, 24(2): 94-112.

The Animation Workshop (2010) Abuela Grillo, available: https://vimeo.com/11429985. (accessed 27 September 2019).

The Future We Need (2016) Digging At Our Conscience, available: https://www.unanima-international.org/wp-content/uploads/digging.pdf (accessed 27 September 2019).

The World Bank Group (2017) ‘The Growing Role of Minerals and Metals for a Low Carbon Future’, available: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/207371500386458722/pdf/117581-WP-P159838-PUBLIC-ClimateSmartMiningJuly.pdf (accessed 16 October 2019)

Toledano, M (2014) ‘Unist’ot’en Camp Evicted a Fracked Gas Pipeline Crew from their Territories’, Vice News, 25 July, available: http://www.vice.com/en_ca/read/unistoten-camp-evicted-a-fracked-gas-pipeline-crew-from-their-territories-985 (accessed 30 July 2019).

Trócaire (2019) ‘Making a Killing: Holding corporations to account for land and human rights violations’, 30 September, Trócaire: Maynooth, available: https://www.trocaire.org/sites/default/files/resources/policy/making_a_killing_holding_corporations_to_account_for_land_and_human_rights_violations_1.pdf (accessed 16 October 2019)

Truelove, Y (2011) ‘(Re-)Conceptualizing water inequality in Delhi, India through a feminist political ecology framework’, Geoforum, 42(2): 143-152.

Veuthey, S & Gerber, J (2012) ‘Accumulation by dispossession in coastal Ecuador: Shrimp farming, local resistance and the gender structure of mobilizations’, Global Environmental Change, 22(3): 611-622.

Warren, K (1997) Ecofeminism: Women, Culture and Nature, Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

WECAN (2019) Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network International, available: https://www.wecaninternational.org (accessed 5 October 2019)

Willow, A & and Keefer, S (2015) ‘Gendering extrACTION: expectations and identities in women’s motives for shale energy opposition’, Journal of Research in Gender Studies, 5(2): 93-120.

Whatmore, S (2002) Hybrid Geographies: Natures, Cultures, Spaces, London: Sage Publications.

V’cenza Cirefice is an ecofeminist researcher and activist who has worked with Plan International, Friends of the Earth Europe and the Women’s Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN). She is a PhD candidate at NUI Galway looking at extractivism through a feminist lens.

Lynda Sullivan works for Friends of the Earth Northern Ireland, supporting communities impacted by extractivism. She lived and worked with communities in Latin America for five years opposing mega-mining.